A Comprehensive Review of Voting Systems and a Proposal For

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Voters' Pamphlet

Washington Elections Division 2925 NE Aloclek Drive, Suite 170 Hillsboro, OR 97124-7523 County www.co.washington.or.us voters’ pamphlet VOTE-BY-MAIL PRIMARY ELECTION May 19, 2020 To be counted, voted ballots must be in our office by 8:00 p.m. on May 19, 2020 ATTENTION This is your county voters’ pamphlet. Washington County Elections prints information as submitted. We do not Washington County correct spelling, punctuation, grammar, syntax, errors or Board of County inaccurate information. All information contained in this Commissioners county pamphlet has been assembled and printed by Rich Hobernicht, County Clerk-Ex Officio, Director Washington County Assessment & Taxation. Kathryn Harrington, Chair Dick Schouten, District 1 Pam Treece, District 2 Roy Rogers, District 3 Dear Voter: Jerry Willey, District 4 This pamphlet contains information for several districts and there may be candidates/measures included that are not on your ballot. If you have any questions, call 503-846-5800. WC-1 Washington County Sheriff Sheriff Red Pat Wortham Garrett Occupation: Sheriff’s Sergeant, Occupation: Sheriff Washington County Occupational Background: Occupational Background: WCSO; patrol deputy, investigator, Sheriff’s Office since 2004; Drug sergeant, lieutenant, division com- Treatment Counselor, Tualatin Valley mander, chief deputy, undersheriff. Mental Health; Ranked #1 on promotional list for Lieutenant, 2015 Educational Background: Oregon State University, Spanish, Educational Background: BA, Bachelors; Portland State University, cum laude, Pacific -

Are Condorcet and Minimax Voting Systems the Best?1

1 Are Condorcet and Minimax Voting Systems the Best?1 Richard B. Darlington Cornell University Abstract For decades, the minimax voting system was well known to experts on voting systems, but was not widely considered to be one of the best systems. But in recent years, two important experts, Nicolaus Tideman and Andrew Myers, have both recognized minimax as one of the best systems. I agree with that. This paper presents my own reasons for preferring minimax. The paper explicitly discusses about 20 systems. Comments invited. [email protected] Copyright Richard B. Darlington May be distributed free for non-commercial purposes Keywords Voting system Condorcet Minimax 1. Many thanks to Nicolaus Tideman, Andrew Myers, Sharon Weinberg, Eduardo Marchena, my wife Betsy Darlington, and my daughter Lois Darlington, all of whom contributed many valuable suggestions. 2 Table of Contents 1. Introduction and summary 3 2. The variety of voting systems 4 3. Some electoral criteria violated by minimax’s competitors 6 Monotonicity 7 Strategic voting 7 Completeness 7 Simplicity 8 Ease of voting 8 Resistance to vote-splitting and spoiling 8 Straddling 8 Condorcet consistency (CC) 8 4. Dismissing eight criteria violated by minimax 9 4.1 The absolute loser, Condorcet loser, and preference inversion criteria 9 4.2 Three anti-manipulation criteria 10 4.3 SCC/IIA 11 4.4 Multiple districts 12 5. Simulation studies on voting systems 13 5.1. Why our computer simulations use spatial models of voter behavior 13 5.2 Four computer simulations 15 5.2.1 Features and purposes of the studies 15 5.2.2 Further description of the studies 16 5.2.3 Results and discussion 18 6. -

Section 10 Correspondence

SECTION 10 CORRESPONDENCE SECTION 10: CORRESPONDENCE Yvonne Galletta Subject: FW: Expansion of my September 22nd comments to the Santa Clara Charter Review Committee Attachments: Portland-Mayorai-Sample-Ballot.pdf Portland-Mayora !-Sample-Ballot. .. ---- - Original Message----- From: Steve Chessin (mailto:steve.chessin®gmail .com] On Behalf Of Steve Chessin Sent: Friday, September 23, 2011 9:43 PM To: Manager Cc: Cl erk Subject: Expansion of my September 22nd comments to t he Santa Clara Charter Review Committee To the members of the Charter Review Committee and supporting City Staff: I would like to expand on the comments I made at the September 22nd Charter Review Committee (CRC) meeting. I made four points, which I expand on here. 1. The minutes of the September 1st meeting contain this sentenc~ under item 7, \•/here it is reporting on my presentation to the CRC: "He referred to a book, 'To Keep Or Change First Past The Post? The Politics of Electoral Reform ' as a good reference . " That is not the book I referred to . In fact, I am not familiar with that book, and had not heard of it until I read its title in the minutes . I do not know if it will be useful to you or not . The books I did refer to are these: Amy , Doug; "Behind the Ballot Box: A Citizen's Guide t o Voting Systems"; Praeger Publishing; Westport, Connecticut; 2 000. It is available at http: //\·Mw. mtholyoke. edu/acad/polit/damy/OrderDesk/behind_ the_ballot_box . htm Reynolds, Andrew, and Reilly, Ben; "The International IDEA Handbook of Electoral System Design"; International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assis tance; Sweden; 1997. -

Single-Winner Voting Method Comparison Chart

Single-winner Voting Method Comparison Chart This chart compares the most widely discussed voting methods for electing a single winner (and thus does not deal with multi-seat or proportional representation methods). There are countless possible evaluation criteria. The Criteria at the top of the list are those we believe are most important to U.S. voters. Plurality Two- Instant Approval4 Range5 Condorcet Borda (FPTP)1 Round Runoff methods6 Count7 Runoff2 (IRV)3 resistance to low9 medium high11 medium12 medium high14 low15 spoilers8 10 13 later-no-harm yes17 yes18 yes19 no20 no21 no22 no23 criterion16 resistance to low25 high26 high27 low28 low29 high30 low31 strategic voting24 majority-favorite yes33 yes34 yes35 no36 no37 yes38 no39 criterion32 mutual-majority no41 no42 yes43 no44 no45 yes/no 46 no47 criterion40 prospects for high49 high50 high51 medium52 low53 low54 low55 U.S. adoption48 Condorcet-loser no57 yes58 yes59 no60 no61 yes/no 62 yes63 criterion56 Condorcet- no65 no66 no67 no68 no69 yes70 no71 winner criterion64 independence of no73 no74 yes75 yes/no 76 yes/no 77 yes/no 78 no79 clones criterion72 81 82 83 84 85 86 87 monotonicity yes no no yes yes yes/no yes criterion80 prepared by FairVote: The Center for voting and Democracy (April 2009). References Austen-Smith, David, and Jeffrey Banks (1991). “Monotonicity in Electoral Systems”. American Political Science Review, Vol. 85, No. 2 (June): 531-537. Brewer, Albert P. (1993). “First- and Secon-Choice Votes in Alabama”. The Alabama Review, A Quarterly Review of Alabama History, Vol. ?? (April): ?? - ?? Burgin, Maggie (1931). The Direct Primary System in Alabama. -

Governance in Decentralized Networks

Governance in decentralized networks Risto Karjalainen* May 21, 2020 Abstract. Effective, legitimate and transparent governance is paramount for the long-term viability of decentralized networks. If the aim is to design such a governance model, it is useful to be aware of the history of decision making paradigms and the relevant previous research. Towards such ends, this paper is a survey of different governance models, the thinking behind such models, and new tools and structures which are made possible by decentralized blockchain technology. Governance mechanisms in the wider civil society are reviewed, including structures and processes in private and non-profit governance, open-source development, and self-managed organisations. The alternative ways to aggregate preferences, resolve conflicts, and manage resources in the decentralized space are explored, including the possibility of encoding governance rules as automatically executed computer programs where humans or other entities interact via a protocol. Keywords: Blockchain technology, decentralization, decentralized autonomous organizations, distributed ledger technology, governance, peer-to-peer networks, smart contracts. 1. Introduction This paper is a survey of governance models in decentralized networks, and specifically in networks which make use of blockchain technology. There are good reasons why governance in decentralized networks is a topic of considerable interest at present. Some of these reasons are ideological. We live in an era where detailed information about private individuals is being collected and traded, in many cases without the knowledge or consent of the individuals involved. Decentralized technology is seen as a tool which can help protect people against invasions of privacy. Decentralization can also be viewed as a reaction against the overreach by state and industry. -

Democracy Lost: a Report on the Fatally Flawed 2016 Democratic Primaries

Democracy Lost: A Report on the Fatally Flawed 2016 Democratic Primaries Election Justice USA | ElectionJusticeUSA.org | [email protected] Table of Contents I. INTRODUCTORY MATERIAL........................................................................................................2 A. ABOUT ELECTION JUSTICE USA...............................................................................................2 B. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY...............................................................................................................2 C. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS..............................................................................................................7 II. SUMMARY OF DIRECT EVIDENCE FOR ELECTION FRAUD, VOTER SUPPRESSION, AND OTHER IRREGULARITIES.......................................................................................................7 A. VOTER SUPPRESSION..................................................................................................................7 B. REGISTRATION TAMPERING......................................................................................................8 C. ILLEGAL VOTER PURGING.........................................................................................................8 D. EVIDENCE OF FRAUDULENT OR ERRONEOUS VOTING MACHINE TALLIES.................9 E. MISCELLANEOUS........................................................................................................................10 F. ESTIMATE OF PLEDGED DELEGATES AFFECTED................................................................11 -

Crowdsourcing Applications of Voting Theory Daniel Hughart

Crowdsourcing Applications of Voting Theory Daniel Hughart 5/17/2013 Most large scale marketing campaigns which involve consumer participation through voting makes use of plurality voting. In this work, it is questioned whether firms may have incentive to utilize alternative voting systems. Through an analysis of voting criteria, as well as a series of voting systems themselves, it is suggested that though there are no necessarily superior voting systems there are likely enough benefits to alternative systems to encourage their use over plurality voting. Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................... 3 Assumptions ............................................................................................................................... 6 Voting Criteria .............................................................................................................................. 10 Condorcet ................................................................................................................................. 11 Smith ......................................................................................................................................... 14 Condorcet Loser ........................................................................................................................ 15 Majority ................................................................................................................................... -

2016 US Presidential Election Herrade Igersheim, François Durand, Aaron Hamlin, Jean-François Laslier

Comparing Voting Methods: 2016 US Presidential Election Herrade Igersheim, François Durand, Aaron Hamlin, Jean-François Laslier To cite this version: Herrade Igersheim, François Durand, Aaron Hamlin, Jean-François Laslier. Comparing Voting Meth- ods: 2016 US Presidential Election. 2018. halshs-01972097 HAL Id: halshs-01972097 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-01972097 Preprint submitted on 7 Jan 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. WORKING PAPER N° 2018 – 55 Comparing Voting Methods: 2016 US Presidential Election Herrade Igersheim François Durand Aaron Hamlin Jean-François Laslier JEL Codes: D72, C93 Keywords : Approval voting, range voting, instant runoff, strategic voting, US Presidential election PARIS-JOURDAN SCIENCES ECONOMIQUES 48, BD JOURDAN – E.N.S. – 75014 PARIS TÉL. : 33(0) 1 80 52 16 00= www.pse.ens.fr CENTRE NATIONAL DE LA RECHERCHE SCIENTIFIQUE – ECOLE DES HAUTES ETUDES EN SCIENCES SOCIALES ÉCOLE DES PONTS PARISTECH – ECOLE NORMALE SUPÉRIEURE INSTITUT NATIONAL DE LA RECHERCHE AGRONOMIQUE – UNIVERSITE PARIS 1 Comparing Voting Methods: 2016 US Presidential Election Herrade Igersheim☦ François Durand* Aaron Hamlin✝ Jean-François Laslier§ November, 20, 2018 Abstract. Before the 2016 US presidential elections, more than 2,000 participants participated to a survey in which they were asked their opinions about the candidates, and were also asked to vote according to different alternative voting rules, in addition to plurality: approval voting, range voting, and instant runoff voting. -

Approval Voting a Characterization and a Compilation of Advantages and Drawbacks in Respect of Other Voting Procedures

Die approbierte Originalversion dieser Diplom-/Masterarbeit ist an der Hauptbibliothek der Technischen Universität Wien aufgestellt (http://www.ub.tuwien.ac.at). The approved original version of this diploma or master thesis is available at the main library of the Vienna University of Technology (http://www.ub.tuwien.ac.at/englweb/). Ao.Univ.Prof. Dipl.-Ing. Dr.techn. Alexander Mehlmann DIPLOMARBEIT Approval Voting A characterization and a compilation of advantages and drawbacks in respect of other voting procedures ausgef¨uhrtam Institut f¨ur Wirtschaftsmathematik der Technischen Universit¨atWien unter Anleitung von Ao.Univ.Prof. Dipl.-Ing. Dr.techn. Alexander Mehlmann durch Michael Maurer Guglgasse 6/2/268 1110 Wien Wien, am 16. Oktober 2007 Michael Maurer Abstract This diploma thesis gives a characterization and a compilation of advantages and drawbacks of approval voting in respect of other voting procedures. Approval voting is a voting procedure, where voters can approve of as many candidates as they like, therefore casting a vote for every candidate they approve of. After a short introduc- tion into voting and social choice theory, and the presentation of two discouraging results (Arrow's theorem and the Gibbard-Satterthwaite theorem), the present work evaluates approval voting by some standard social choice criteria. Then, it character- izes approval voting among ballot aggregation functions, it characterizes candidates who can win approval voting elections, and provides advice to voters on what strate- gies they should employ according to their preference ranking. The main part of this work compiles advantages and disadvantages of approval voting as far as dichoto- mous, trichotomous and multichotomous preferences, strategy-proofness, election of Pareto and Condorcet candidates, stability of outcomes, Condorcet efficiency, comparison of outcomes to other voting procedures, computational manipulation, vulnerability to majority decisiveness and to the erosion of the majority principle, and subset election outcomes are concerned. -

Selecting Representative and Qualified Candidates for President

Selecting Representative and Qualifed Candidates for President: Proposals to Reform Presidential Primaries Democracy and the Consttuton Clinic Fordham University School of Law Daisy de Wolf, Ben Kremnitzer, Samara Perlman, & Gabriella Weick January 2021 Selecting Representative and Qualifed Candidates for President: Proposals to Reform Presidential Primaries Democracy and the Consttuton Clinic Fordham University School of Law Daisy de Wolf, Ben Kremnitzer, Samara Perlman, & Gabriella Weick January 2021 This report was researched and writen during the 2019-2020 academic year by students in Fordham Law School’s Democracy and the Consttuton Clinic, where students developed non-partsan recommendatons to strengthen the naton’s insttutons and its democracy. The clinic was supervised by Professor and Dean Emeritus John D. Feerick and Visitng Clinical Professor John Rogan. Acknowledgments: We are grateful to the individuals who generously took tme to share their general views and knowledge with us: Robert Bauer, Esq., Professor Monika McDermot, Thomas J. Schwarz, Esq., Representatve Thomas Suozzi, and Jesse Wegman, Esq. This report greatly benefted from Gail McDonald’s research guidance and Flora Donovan’s editng assistance. Judith Rew and Robert Yasharian designed the report. Table of Contents Executve Summary .....................................................................................................................................1 Introducton .....................................................................................................................................................4 -

Selecting the Runoff Pair

Selecting the runoff pair James Green-Armytage New Jersey State Treasury Trenton, NJ 08625 [email protected] T. Nicolaus Tideman Department of Economics, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University Blacksburg, VA 24061 [email protected] This version: May 9, 2019 Accepted for publication in Public Choice on May 27, 2019 Abstract: Although two-round voting procedures are common, the theoretical voting literature rarely discusses any such rules beyond the traditional plurality runoff rule. Therefore, using four criteria in conjunction with two data-generating processes, we define and evaluate nine “runoff pair selection rules” that comprise two rounds of voting, two candidates in the second round, and a single final winner. The four criteria are: social utility from the expected runoff winner (UEW), social utility from the expected runoff loser (UEL), representativeness of the runoff pair (Rep), and resistance to strategy (RS). We examine three rules from each of three categories: plurality rules, utilitarian rules and Condorcet rules. We find that the utilitarian rules provide relatively high UEW and UEL, but low Rep and RS. Conversely, the plurality rules provide high Rep and RS, but low UEW and UEL. Finally, the Condorcet rules provide high UEW, high RS, and a combination of UEL and Rep that depends which Condorcet rule is used. JEL Classification Codes: D71, D72 Keywords: Runoff election, two-round system, Condorcet, Hare, Borda, approval voting, single transferable vote, CPO-STV. We are grateful to those who commented on an earlier draft of this paper at the 2018 Public Choice Society conference. 2 1. Introduction Voting theory is concerned primarily with evaluating rules for choosing a single winner, based on a single round of voting. -

The Plurality-With-Elimination Method (PWE)

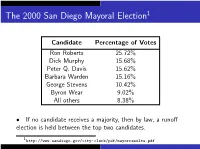

The 2000 San Diego Mayoral Election1 Candidate Percentage of Votes Ron Roberts 25.72% Dick Murphy 15.68% Peter Q. Davis 15.62% Barbara Warden 15.16% George Stevens 10.42% Byron Wear 9.02% All others 8.38% • If no candidate receives a majority, then by law, a runoff election is held between the top two candidates. 1http://www.sandiego.gov/city-clerk/pdf/mayorresults.pdf Example: The 2000 San Diego Mayoral Election Practical problems with this system: I Runoff elections cost time and money I Ties (or near-ties) for second place I Preference ballots provide a method of holding an “instant-runoff" election: the Plurality-with-Elimination Method (PWE). 2. If no candidate has received a majority, then eliminate the candidate with the fewest first-place votes. 3. Repeat steps 1 and 2 until some candidate has a majority, then declare that candidate the winner. The Plurality-with-Elimination Method (x1.4) 1. Count the first-place votes. If some candidate receives a majority of the first-place votes, then that candidate is the winner. 3. Repeat steps 1 and 2 until some candidate has a majority, then declare that candidate the winner. The Plurality-with-Elimination Method (x1.4) 1. Count the first-place votes. If some candidate receives a majority of the first-place votes, then that candidate is the winner. 2. If no candidate has received a majority, then eliminate the candidate with the fewest first-place votes. The Plurality-with-Elimination Method (x1.4) 1. Count the first-place votes. If some candidate receives a majority of the first-place votes, then that candidate is the winner.