Debs, Eugene Victor (5 Nov

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dr. Henry C. Black Dies Shepard Receives Great Freshmen Defeated in St

l'he Undergraduate Publication of ~tinitp t ' C!tolltge Volume XXIII HARTFORD, CONN., FRIDAY, M.A!R:CH 25, 1927 Number 22 DR. HENRY C. BLACK DIES SHEPARD RECEIVES GREAT FRESHMEN DEFEATED IN ST. OGILBY DISCUSSES STUDENT JUNIOR 'VARSITY HONOR. PATRICK'S DAY SCRAP. SUICIDES. BASKETBALl.. Was Recently Elected Trustee and Lays Part Blame on Church Awarded Guggenheim Fellowship S<•phomores Show Efficient Organiza Leeke's Men Make Creditable Long a Prominent Alumnus. Formalism. for 1927-28. tion. Showing. Dr. Henry Campbell Black, 67 years Formalisms of the church that run Professor Odell Shepard, Goodwin · About the seventh hour on th(> The Junior 'Varsity basketball years old, law ·author and editor of the cNmter to the experience of college .Professor of English Literature and morning of March 17, in the year o: proved to be one of the bright lights "Constitutional Review," died Satur cur Lord 1927, it befell that the mem f. tudents are partly responsible for of the basketball season. While the day afternoon at 2.45 o'clock at his head of the English department, has been awarded a Guggenheim Fellow bers of the Class of '29, duly enrolled many student suicides, in the opinion 'varsity was unable to score many 1·esidence, 2516 Fourteenth Street, of President Remsen B. Ogilby. ship for the year 1927-28. The fel 1n Trinity College, handed to the viotories to their credit the juniors Washington, D. C., after an illness of "Of grave concern to us," said Dr. lowship is one of those awarded by members of the Class of '30 what made the fine record of eleven wins three weeks. -

New Masses Index 1926 - 1933 New Masses Index 1934 - 1935 New Masses Index 1936

NEW MASSES INDEX 1936 NEW MASSES INDEX NEW MASSES INDEX 1936 By Theodore F. Watts Copyright 2007 ISBN 0-9610314-0-8 Phoenix Rising 601 Dale Drive Silver Spring, Maryland 20910-4215 Cover art: William Sanderson Regarding these indexes to New Masses: These indexes to New Masses were created by Theodore Watts, who is the owner of this intellectual property under US and International copyright law. Mr. Watts has given permission to the Riazanov Library and Marxists.org to freely distribute these three publications… New Masses Index 1926 - 1933 New Masses Index 1934 - 1935 New Masses Index 1936 … in a not for profit fashion. While it is my impression Mr. Watts wishes this material he created be as widely available as possible to scholars, researchers, and the workers movement in a not for profit fashion, I would urge others seeking to re-distribute this material to first obtain his consent. This would be mandatory, especially, if one wished to distribute this material in a for sale or for profit fashion. Martin H. Goodman Director, Riazanov Library digital archive projects January 2015 Patchen, Rebecca Pitts, Philip Rahv, Genevieve Taggart, Richard Wright, and Don West. The favorite artist during this two-year span was Russell T. Limbach with more than one a week for the run. Other artists included William Gropper, John Mackey, Phil Bard, Crockett Johnson, Gardner Rea, William Sanderson, A. Redfield, Louis Lozowick, and Adolph Dehn. Other names, familiar to modem readers, abound: Bernarda Bryson and Ben Shahn, Maxwell Bodenheim, Erskine Caldwell, Edward Dahlberg, Theodore Dreiser, Ilya Ehrenberg, Sergei Eisenstein, Hanns Eisler, James T. -

PARTY. 303 Fourth AVE.E HEW Yo.Ak·J Q

PARTY. 303 fOURTH AVE.e HEW yo.aK ·~JQ "Freedom for All" Pamphlets This is the third of a new pamphlet series, "FREEDOM FOR ALL," published by the Socialist Party. The first was "VICTORY'S VICTIMS? ," a discussion of the Negro's future, by A. Philip Randolph and Norman Thomas. The second was "ITALY-VICTORY THROUGH REV OLUTION," by Roy Curtis. The next will be "WAR AGAINST WANT," a discussion of social security and full employment by Professor Mul ford Sibley. The fifth will be "PEACE WITH FREEDOM," a pro gram of Socialist peace aims, by Travers Clement. Special rates for these pamphlets are: 1 copy -- $ .10 3 copies -- .25 15 copies -- 1.00 100 copies -- 5.00 • Order From SOCIALIST PARTY 303 Fourth Avenue, New York 10, N. Y. GRamercy 7-9584 Published December 1943 o I 7 L·n 0 d Detr It 6 y ich;gan The Truth About Socialism By NORMAN THOMAS CHAPTER I ON'T read this pamphlet if you are afraid to know the D truth about socialism or fear that you might be per suaded to be a socialist. Don't read it if you think every thing is going to be lovely in America regardless of what you do about liberty, peace, jobs and plenty for all. But why another pa~phlet, you ask, when the books on socialism already existing could be piled' mountain high? The answer is, first, because misunderstandings of it h~ve been increased by the propaganda of its enemies and its false friends: and, second because the march of events makes necessary some reinterpretation of its essential prin ciples and their application. -

Morris Leopold Ernst

Morris Leopold Ernst: An Inventory of His Papers at the Harry Ransom Center Descriptive Summary Creator: Ernst, Morris Leopold, 1888-1976 Title: Morris Leopold Ernst Papers Dates: 1904-2000, undated Extent: 590 boxes (260.93 linear feet), 47 galley folders (gf), 29 oversize folders (osf) Abstract: The career and personal life of American attorney and author Morris L. Ernst are documented from 1904 to 2000 through correspondence and memoranda; research materials and notes; minutes, reports, briefs, and other legal documents; handwritten and typed manuscripts; galley proofs; clippings; scrapbooks; audio recordings; photographs; and ephemera. The papers chiefly reflect the variety of issues Ernst dealt with professionally, notably regarding literary censorship and obscenity, but also civil liberties and free speech; privacy; birth control; unions and organized labor; copyright, libel, and slander; big business and monopolies; postal rates; literacy; and many other topics. Call Number: Manuscript Collection MS-1331 Language: English Note: The Ransom Center gratefully acknowledges the assistance of the National Endowment for the Humanities, which provided funds for the preservation and cataloging of this collection. Arrangement Due to size, this inventory has been divided into four separate units which can be accessed by clicking on the highlighted text below: Morris Leopold Ernst Papers--Series descriptions and Series I. through Series II., container 302.2 [Part I] Morris Leopold Ernst Papers--Series II. (continued), container 302.3 through -

Copyright I L L Ton Lawii Far Her

Copyright ill ton Lawii Far her, Jr. 1?59 I CHANGING ATTI1UDBB OP THE AMERICAN FEDERATION OF LABOR TOWARD BUSINESS AID OOVSUBBMT 1929-1933 DBSBtTATIOS Rnmitod In Partial JhlflUaant of tho Raqulraaanta for tha Dacr«o Dootor of fhiloaephy In tha fraduats flehool of tha Ohio Stata UnivsrsHy By MILTON I S I S FARBBRf J R ., B. A ., M. A. Tha Ohio Stata Unlraraity 1959 Jppro*ad by Dapartaant of History ACKNMUSDGSMSra In tha preparation of thle dissertation* the author has incurred manor debts* to Hr. Jeorge Hsany for permission to use the Minutes of the AFL Executive Council; to Mrs. Eloise Ciles and her staff at the AFL-CIO librarj; to Hr. laroel Pittat of tha State Historical Society of VUsoonsin; to the staff of the Manuscripts Division of the Library of Congress; to Mrs. Wanda Rife, Miss Jans Catliff and Miss Hazel Johnson of the Ohio State University library; and to frofessor Alma Hsrbst of the Economics Department of the Ohio State University for her many kindnesses. The award of a William (keen Fellowship by the Ohio State University made possible the completion of this dissertation, lastly , the author acknowledges with gratitude the p ersisten t In terest and c r itic a l insight of Professor Foster Rhea Dulles which proved Invaluable throughout the preparation of the work. i i TAB IS OF CONTENTS Chapter Pag* I . GROANIZED LABOR ON THE EVE OF TUB DEPRESSION........................... 1 H . IKS SLA OF PERSUASION AND THE IEQACI OF QONPTOS.......................... 33 III* LABOR AND THE CRASH* 1929-30 * . • . ..................... 63 IV. -

Download This PDF File

Political Ethics and Public Style in the Early Career of Jersey City’s Frank Hague Matthew Taylor Raffety1 Abstract This essay charts the political rise of Frank Hague, Jersey City's infamous mayor from 1917-1947. Although most historical attention focuses on his long tenure as mayor, Hague's pre-mayoral career provides an instructive example of how urban politicians used public spectacle, the media, ethnic identity, and middle class mores to redefine American urban politics. Before becoming mayor, Hague crafted a public persona that appealed to both middle-class and working-class ethnic voters by reinventing himself as a Progressive while still retaining the showmanship and personal appeals of machine politics. Hague straddled two distinct political traditions, presenting himself simultaneously as a "pol," rooted in the historical mores of the ―Horseshoe,‖ his home neighborhood, as well as a good government advocate, appealing to Jersey City's native-born middle class—focusing on clean water, public safety, and personal responsibility. In doing so, Hague provided a template for ethnic reform mayors who followed, from Fiorello LaGuardia and Richard Daley to Rudolph Giuliani and Ed Rendell. ―For better or worse, he knew how to run a show.‖2 Of all the political bosses who ruled the cities of the American East and Midwest at the beginning of the twentieth century, perhaps none was as feared, demonized, and beloved as Frank Hague of Jersey City, New Jersey (Figure 1). Curiously, however, the man who commanded the attention of contemporaries has received scant attention since his machine was ―buried‖ with a symbolic funeral in May of 1949.3 Contemporaries and historians describe Hague (1876-1956) as the archetypal American political boss. -

Kay Moor, New River Gorge National River, West Virginia

29.58/3-.N 42 I Ka.. Resource Study, «lricHistoric historic resource study Clemson Universi PUBLIC DOCUMEHTfc " pEPOSITORY ITE1* 3 1604 019 472 622 OCT 1 1990 CLEMSON LH&RARY KAY MOOR NEW RIVER GORGE NATIONAL RIVER • WEST VIRGINIA historic resource study by Sharon A. Brown July 1990 KAY MOOR NEW RIVER GORGE NATIONAL RIVER • WEST VIRGINIA UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR / NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2012 with funding from LYRASIS Members and Sloan Foundation http://archive.org/details/historicresourceOOriver CONTENTS Page PREFACE vii INTRODUCTION ix CHAPTER ONE: FAYETTE COUNTY COAL 1 Fayette County 1 Use of "Smokeless" Coal 3 Low Moor Iron Company 5 Opening the West Virginia Mines 7 New River and Pocahontas Consolidated Coal and Coke Company 10 Influence of West Virginia Coal Production 12 CHAPTER TWO: THE KAY MOOR MINE 15 Kay Moor No. 1 15 Kay Moor No. 2 17 Kay Moor Coke 18 The Miners 20 Immigrant Miners 20 Black Miners 23 Mine Safety 29 Mining Skills 33 Wages 35 World War I 36 Labor 37 CHAPTER THREE: THE TOWN OF KAY MOOR 57 Coal Towns 57 Kay Moor Demographics 62 Evolution and Layout of Kay Moor 63 Company Housing 66 Coal Town Architecture 69 Transportation 70 Sanitation 72 Lighting 73 Fences 73 Sidewalks 73 Fuel 73 Medical Care 74 Police 74 Company Store 74 Schools 79 Churches and Cemetery 80 Post Office 81 Bank 82 Recreational and Social Activities 82 Gardens and Hunting 84 Alcohol 85 Mobility 86 in Page Other Employment Opportunities 87 Abandonment of Kay Moor Top and Bottom 88 RECOMMENDATIONS FOR FURTHER RESEARCH 90 HISTORICAL BASE MAPS 91 APPENDIXES 99 Appendix 1: Shipping Statement, The Low Moor Iron Company of Virginia, April 17, 1903 101 Appendix 2: Managers of Kay Moor No. -

Convert Finding Aid To

Morris Leopold Ernst: An Inventory of His Papers at the Harry Ransom Center Descriptive Summary Creator: Ernst, Morris Leopold, 1888-1976 Title: Morris Leopold Ernst Papers Dates: 1904-2000, undated Extent: 590 boxes (260.93 linear feet), 47 galley folders (gf), 30 oversize folders (osf) Abstract: The career and personal life of American attorney and author Morris L. Ernst are documented from 1904 to 2000 through correspondence and memoranda; research materials and notes; minutes, reports, briefs, and other legal documents; handwritten and typed manuscripts; galley proofs; clippings; scrapbooks; audio recordings; photographs; and ephemera. The papers chiefly reflect the variety of issues Ernst dealt with professionally, notably regarding literary censorship and obscenity, but also civil liberties and free speech; privacy; birth control; unions and organized labor; copyright, libel, and slander; big business and monopolies; postal rates; literacy; and many other topics. Call Number: Manuscript Collection MS-1331 Language: English Note: The Ransom Center gratefully acknowledges the assistance of the National Endowment for the Humanities, which provided funds for the preservation and cataloging of this collection. Access: Open for research Administrative Information Acquisition: Gifts and purchases, 1961-2010 (R549, R1916, R1917, R1918, R1919, R1920, R3287, R6041, G1431, 09-06-0006-G, 10-10-0008-G) Processed by: Nicole Davis, Elizabeth Garver, Jennifer Hecker, and Alex Jasinski, with assistance from Kelsey Handler and Molly Odintz, 2009-2012 Repository: The University of Texas at Austin, Harry Ransom Center Ernst, Morris Leopold, 1888-1976 Manuscript Collection MS-1331 Biographical Sketch One of the most influential civil liberties lawyers of the twentieth century, Morris Ernst championed cases that expanded Americans' rights to privacy and freedom from censorship. -

LP001061 0.Pdf

The James Lindahl Papers Papers, 1930s-1950s 29 linear feet Accession #1061 OCLC # DALNET # James Lindahl was born in Detroit in 1911. He served as Recording Secretary for the UAW-CIO Packard Local 190 and edited its newspaper in the 1930s and 1940s. Mr. Lindahl left the local in 1951 feeling that the labor movement no longer had a place for him. He earned a Master's degree from Wayne State University in Sociology in 1954 and later earned his living as a self-employed publisher in the Detroit area in various fields including retail, banking, and medicine. The James Lindahl Collection contains proceedings, reports, newspaper clippings, and election information pertaining to the UAW-CIO and its Packard Local 190 from the 1930s into the early 1950s. It also contains Mr. Lindahl's graduate school papers on local union membership and participation. The collection also contains publications, including pamphlets, books, periodicals, flyers and handbills, from many organizations such as the UAW, CIO, other labor unions and organizations, and the U.S. government from the 1930s into the early 1950s. Important subjects in the collection: UAW-CIO Packard Local 190 Union political activities Union leadership Ku Klux Klan Union membership Packard Motor Car Company 2 James Lindahl Collection CONTENTS 29 Storage Boxes Series I: General files, 1937-1953 (Boxes 1-6) Series II: Publications (Boxes 7-29) NON-MANUSCRIPT MATERIAL Approximately 12 union contracts and by-laws were transferred to the Archives Library. 3 James Lindahl Collection Arrangement The collection is arranged into two series. In Series I (Boxes 1-6), folders are simply listed by location within each box. -

Workers Defense League Records

THE WORKERS DEFENSE LEAGUE COLLECTION Papers, 1935 - 1971 136 1/4 linear feet Accession No. 408 The Workers Defense League placed its historic papers in the Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs in August, 1970, and further additions have been received since then. Founded on August 29, 1936, the WDL was rooted in a nucleus of prior groups, including various chapters of the Labor and Socialist Defense Committee. The suppression of the 1935 strike in Terre Haute, Indiana, the murder of Joseph Shoemaker, an organizer in Tampa, Florida, the cotton choppers' strike in Arkansas, the arrests in New Jersey of people handing out leaflets, and other such incidents, showed the need for an organization to champion the causes of workers in the interest of social and economic justice, and to give such assistance to workers without political cause or party label attached. The Workers Defense League became such an organization. Through the years the WDL expanded its activities; it was the legal arm and financial backer of the Southern Tenant Farmers Union; gave assistance on immigration and deportation cases, loyalty-security cases, passports, refugees, conscientious objectors, civil rights, union democracy, minority apprenticeship training, military and conscription cases, and many more. Note: The Workers Defense League gave some files of Conscientious Objector Cases (1945-1948) to the Swarthmore Peace Library at Swarthmore, Pennsylvania. They are filed there under "Metropolitan Board for Conscientious Objectors." Other Conscientious Objector cases are in- cluded here. Norman Thomas, David Clendenin, George S. Counts, Harry Fleischman, Aron Gilmartin, Albert K. Herling, Morris Milgram, Rowland Watts, and Vera Rony were only a few of the active officers, others to be found in the correspondents list below. -

Eugene Victor Debs (1855-1926)

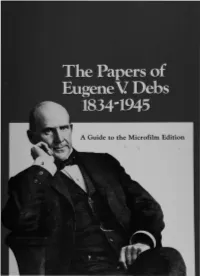

A Guide to the Microfilm Edition Pro uesf Start here. This volume is a finding aid to a ProQuest Research Collection in Microform. To learn more visit: www.proquest.com or call (800) 521-0600 About ProQuest: ProQuest connects people with vetted, reliable information. Key to serious research, the company has forged a 70-year reputation as a gateway to the world's knowledge-from dissertations to governmental and cultural archives to news, in all its forms. Its role is essential to libraries and other organizations whose missions depend on the delivery of complete, trustworthy information. 789 E. Eisenhower Parkw~y • P.O Box 1346 • Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 • USA •Tel: 734.461.4700 • Toll-free 800-521-0600 • www.proquest.com The Papers of Eugene V. Debs 1834-1945 A Guide to the Microfilm Edition J. Robert Constantine Gail Malmgreen Editor Associate Editor ~ Microfilming Corporation of America A New York Times Company 1983 Cover Design by Dianne Scoggins No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, by photostat, microfilm, xerography, or any other means, or incorporated into any information retrieval system, electronic or mechanical, without the written permission of the copyright owner. Copyright© 1983, MICROFILMING CORPORATION OF AMERICA ISBN 0-667-00699-0 Table of Contents Acknowledgments ............................................................................ v Note to the Researcher .................................................................... vii Eugene Victor Debs (1855-1926) ........................................................ -

American Civil Liberties Union Pamphlets, 1913-1937, (C2537)

C American Civil Liberties Union Pamphlets, 1913-1937 2537 1.6 linear feet This collection is available at The State Historical Society of Missouri. If you would like more information, please contact us at [email protected]. INTRODUCTION The papers contain printed pamphlets and reports on issues involving civil liberties, published by the American Civil Liberties Union and such related organizations as the Free Speech League and the League for Industrial Democracy. Also included is miscellaneous socialist and communist literature. DONOR INFORMATION The papers were transferred to the University of Missouri form the UMC Ellis Library on 28 March 1968 (Accession No. 3752). FOLDER LIST f. 1 "On Liberty of the Press for Advocating Resistance to Government Being Part of an Essay Written for the Encyclopedia Britannica, Sixth Edition, 1821." James Mill. Reprinted, with introduction by Theodore Schroeder, by the Free Speech League, New York, 1913. f. 2 "Some Aspects of the Constitutional Questions Involved in the Draft Act of May 18, 1917." New York and Washington, American Union Against Militarism. f. 3 "The War and the Intellectuals," Randolph Bourne. Reprinted from The Seven Arts (June 1917) by the American Union Against Militarism, New York. f. 4 "Constitutional Rights in War Time." New York, American Union Against Militarism, 1917. f. 5 "'Not Guilty!' Chicago, National Office of the Socialist Party, 1917. f. 6 "National Civil Liberties Bureau." New York, National Civil Liberties Bureau, November, 1917. f. 7 "Liberty in Wartime! The issue in the United States today in the light of England's experience." Alice Edgerton. Reprinted from the New York Evening Post (December 20, 1917).