Feature Articles: Maternal Aggression As Women's Empowerment In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Banyai -L.Roldán -Isolg.Roldán -Gusti La Literatura Infantil Ysucultura Reflexiones Sobre #1 Edición Digital SUMARIO / 1

Banyai - Gusti - Isol - G. Roldán - L. Roldán Reflexiones sobre culturala literatura infantil y su cultura lij #1 Edición digital Año 1 / Número 1. ISBN: Mayo 2013. en trámite. 1. ISBN: Mayo 1 / Número Año SUMARIO / 1 Editorial Biografia lectora Paren las rotativas Crecí en una casa biblioteca 2 Laura Demidovich y Valeria Sorín Laura Roldán 15 Politica Instrucciones para darle 1 a 1 3 cuerda al Martín Fierro Libros al resguardo 18 Daniela Allerbon Daniela Azulay Columna de ALIJA Grandes méritos, nuevos logros Reportaje 22 6 Pilar Muñoz Lascano Un verdadero Gusti Homenaje Novedades 8 Mirar con Isol 26 Biblioteca protagonista 10 La identidad de una comunidad Agenda Verónica Cantelmo 28 De fondo Espacio editorial Un catálogo para recorrer Los cuatro azules 34 14 Diego Javier Rojas cultura lij Edición digital Reflexiones sobre la literatura infantil y su cultura Ilustración de Tapa: Santiago Caruso Queda prohibida la reproducción total o Año 1 – Número 1 – Mayo 2013 Fotografía: Laura Demidovich parcial del contenido de esta publicación sin Cultura LIJ es una publicación de Editorial La Bohemia. ISSN: en trámite. consentimiento previo de la editorial. Vuelta de Obligado 3567 PB "C" (1429) CABA. Tel: (011) 3534-1975 Agradecimientos: A Gustavo Roldán por la [email protected] gentileza de tapa, a la biblioteca de la esc. 26 D. www.culturalij.worpress.com E. 10, a Ileana Falconat, a Gustavo Galárraga, y a www.editoriallabohemia.com Nicolás Pérez por las imágenes y videos de Altavoz. La editorial no se hace responsable de las Directoras responsables: Laura Demidovich opiniones vertidas por sus colaboradores y/o y Valeria Sorín entrevistados. -

Nominees for the Astrid Lindgren Memorial Award 2018 to Be Announced on October 12

Oct 02, 2017 12:06 UTC Nominees for the Astrid Lindgren Memorial Award 2018 to be announced on October 12 The candidates for the Astrid Lindgren Memorial Award 2018 will be presented on October 12 at the Frankfurt Book Fair. So far, seventeen laureates have received the Award, the latest recipient is the German illustrator Wolf Erlbruch. The award amounts to SEK 5 million (approx. EUR 570 000), making it the world's largest award for children's and young adult literature. The list of nominated candidates is a gold mine for anyone interested in international children’s and young adult literature – and would not be possible without the work of more than a hundred nominating bodies from all over the world. Welcome to join us when the list of names is revealed! Programme 12 October at 4 pm CET 4.00 pm Welcome by Gabi Rauch-Kneer, vice president of Frankfurter Buchmesse 4.05 pm Prof. Boel Westin, Chairman of the ALMA Jury and Journalist Marcel Plagemann, present the work of Wolf Erlbruch. 4.40 pm Helen Sigeland, Director of ALMA, about upcoming events. 4.45 pm Prof. Boel Westin, Chairman of the ALMA Jury, reveals the candidates for the 2018 award. The event is a co-operation with the Frankfurt Book Fair and takes place at the Children's Book Centre (Hall 3.0 K 139). The nomination list of 2018 will be available on www.alma.se/en shortly after the programme. Earlier ALMA laureates 2017 Wolf Erlbruch, Germany 2016 Meg Rosoff, United Kingdom/United States 2015 PRAESA, South Africa 2014 Barbro Lindgren, Sweden 2013 Isol, Argentina 2012 Guus Kuijer, -

Boletín De Novedades Biblioteca Pública Del Estado Santa Cruz De Tenerife

Boletín de Novedades Biblioteca Pública del Estado Santa Cruz de Tenerife ABRIL – JUNIO 2009 Boletín de Novedades Biblioteca Pública del Estado Santa Cruz de Tenerife 0 generalidades Explora / Sean Callery, Clive Gifford y Mike Goldsmith. -- Madrid : San Pablo, cop. 2008 (03) CAL exp ¿Por qué los mocos son verdes? : y otras preguntas (y respuestas) sobre la ciencia / Glenn Murphy ; ilustraciones de Mike Phillips. -- 1 ed. -- Barcelona : Medialive, 2009 001 MUR por Guinnes World Records especial videojuegos 2009 / [editor, Craig Glenday]. -- [Barcelona] : Planeta, [2009] 088 GUI El gran libro de los cuántos / Alain Korkos ; ilustraciones de Rif. -- Barcelona : Oniro, cop. 2009 088 KOR gra 1 filosofía, psicología Filosofía : 100% adolescente / Yves Michaud ; ilustraciones de Manu Boisteau. -- Madrid : San Pablo, [2008] 1 MIC fil Psicología : 100% adolescente / Philippe Jeammet y Odile Amblard ; ilustraciones de Soledad. -- Madrid : San Pablo, [2008] 159 JEA psi 1 Boletín de Novedades Biblioteca Pública del Estado Santa Cruz de Tenerife 2 religión Dios, Yahvé, Alá : los grandes interrogantes en torno a las tres religiones / Katia Mrowiec, Michel Kubler, Antoine Sfeir ; ilustraciones, Olivier André ... [et al.]. -- Barcelona : Edebé, [2006] 21/29 MRO dio 3 ciencias sociales M de mujer / Tomás Abella. -- 2 ed. -- Barcelona : Intermón Oxfam, 2008) 308 ABE mde ¡Aprende a cuidarte! : prevención del abuso sexual infantil para niñas y niños de 7 a 12 años / Antonio Romero Garza. -- 1 ed. -- México D. F. : Trillas ; Alcalá de Guadaíra (Sevilla) : Eduforma, 2008 343 ROM apr Cómo redactar tus exámenes y otros escritos de clase / Joaquín Serrano Serrano ; dirección, Salvador Gutiérrez Ordóñez. -- Madrid : Anaya, 2002 371.27 SER com 2 Boletín de Novedades Biblioteca Pública del Estado Santa Cruz de Tenerife Mi enciclopedia de los niños del mundo / [Stéphanie Ledu]. -

El Libro Álbum Como Propuesta De Lectura / the Picture Book As a Reading Proposal

EL LIBRO ÁLBUM COMO PROPUESTA DE LECTURA Adriana María Fontana Instituto Superior Nuestra Señora del Rosario de Lavalle, Argentina [email protected] Recibido: 26/05/2018. Aceptado: 21/08/2018. Resumen El libro álbum es hoy un género editorial merecedor de la atención de un gran número de especialistas. El objetivo de este artículo es ofrecer un estado de la cuestión sobre este género prestando atención a la bibliografía que se ha ocupado de él como objeto que estimula determinados modos de lectura. Las principales hipótesis que allí pueden rastrearse son: la existencia de una interconexión e interdependencia de dos códigos (texto e ilustración) y el rol activo del lector quien debe construir niveles de sentido a partir de tal dependencia. Nuestro propósito será entonces observar cómo funcionan los distintos recursos y elementos materiales que lo componen a través de breves análisis de casos. El desarrollo contendrá una primera parte donde se describirán las características que particularizan al género; una segunda, que contendrá algunas claves para su lectura; y una tercera, donde se presentarán algunas convenciones gráficas que pueden facilitar su interpretación. Palabras clave: Libro álbum - Imagen - Recursos - Niveles de lectura THE PICTURE BOOK AS A READING PROPOSAL Abstract In today’s literary world, picture book is a genre deserving of a high number of specialist’s attention. This article aims to offer a status on this genre based on the bibliography that focuses on it as object that stimulates certain kinds of reading. The main hypotheses that we find on such bibliography are: the existence of an interconnection and interdependence of two codes (text and illustration), and the active role of the reader, who must build meaningful levels based on said interdependence. -

El Bancodellibro Recomienda

Nº.13 El Banco del Libro recomienda Los mejores libros para niños y jóvenes 2012 Este año nos sentimos dichosos de poder festejar 32 años de este LIBROS PARA NIÑOS LIBROS PARA JÓVENES premio. Continuamos evaluando libros para niños y jóvenes movidos Hripsime Bedrosián Carlos Sandoval por el deseo de prender una pequeña luz y trazar un mapa sobre el Licenciada en Letras por la Universi- Narrador y crítico literario. Se des- Editorial bosque gigante de libros producidos actualmente para este público Jurado dad Católica Andrés Bello. Espe- empeña como docente-investigador lector tan especial. En ese sentido, nuestro quehacer se asemeja cialista en Lectura y Escritura del del Instituto de Investigaciones al de un explorador que examina, se detiene y esboza orientaciones 2 012 Universidad Pedagógica Experimen- Literarias y de la Maestría en Litera- en medio de nuevos territorios. De allí que al confeccionar esta tal Libertador, en proceso de tesis. tura Venezolana de la Universidad Coordinó el programa de Promoción Central de Venezuela. Es profesor de selección aspiramos tender puentes y brújulas entre los libros, de la lectura en escuelas de Edito- las Escuelas de Letras de la Univer- los mediadores y sus lectores finales. rial Santillana. Ha coordinado la sidad Central de Venezuela y de la programación del Pabellón Infantil Universidad Católica Andrés Bello. Este año, la selección de los mejores libros se ha hecho sobre una de la Feria del Libro de Venezuela muestra de 124 libros, en su mayoría dirigidos al público infantil. A en dos oportunidades. Docente de Loredana Volpe las materias Literatura Infantil y Estudió Letras en la Universidad partir de esta muestra, queremos celebrar el destello de las editoria- Lectoescritura. -

Algunos Aportes Sobre Las Nuevas Tendencias En Literatura Infantil Y Juvenil

ALGUNOS APORTES SOBRE LAS NUEVAS TENDENCIAS EN LITERATURA INFANTIL Y JUVENIL Ponencia presentada en la Universidad Interamericana de Puerto Rico Escuela de Educación y Profesiones de la Conducta Cátedra UNESCO para el Mejoramiento de la Lectura y la Escritura Semana de la Lectura Carolina Holmes Banco del Libro ALGUNOS APORTES SOBRE LAS NUEVAS TENDENCIAS EN LITERATURA INFANTIL Y JUVENIL El tema que me sugirieron tratar el día de hoy es el de las nuevas tendencias en la Literatura Infantil y Juvenil, así que me dediqué a la tarea de hacer una revisión bibliográfica sobre los autores que han tratado sobre esto, revisar las novedades que llegan al Comité de Evaluación del Banco del Libro y tratar de componer y organizar las coincidencias entre esas novedades con la teoría reseñada en la bibliografía. Luego de reflexionar sobre lo que estaba realizando, tomé la decisión de hacer esta presentación desde la mirada del evaluador de libros infantiles y juveniles, rol que desempeño desde hace ya más de 8 años en el Banco del Libro. Ingresé en el comité, pues estaba realizando un estudio para mi tesis de Maestría en Lectura y Escritura. Soy docente especialista y para el momento de mi tesis trabajaba en un colegio en un barrio popular en Caracas. Me proponía en un primer momento comparar los criterios de evaluación del Comité del Banco para recomendar libros con los criterios de evaluación que poseían los niños libremente, al escoger que leer o que recomendar leer a otros niños. Tenía la idea de que los adultos evaluadores no tomaban en cuenta la opinión de los niños, usurpando un rol que naturalmente le pertenecía al niño o al joven lector. -

Nominating Bodies for the 2019 Award

Nominating bodies for the 2019 award Algeria Syndicat National des Editeurs des Livres (SNEL) Andorra Biblioteca Nacional d’Andorra Angola Biblioteca Nacional de Angola Antigua & Barbuda Cultural Development Division Argentina Argentinian Section of IBBY Asociación de Ilustradores Argentinos Isol / Laureate 2013 Salmeron IFLA Armenia Armenian Section of IBBY National Library of Armenia Australia Australian Section of IBBY Centre for Youth Literature Children’s Book Council of Australia Illustrators Australia National Library of Australia IFLA Shaun Tan / Laureate 2011 Society of Children’s Book Writers and Illustrators, Australia East/New Zealand Society of Children’s Book Writers and Illustrators, Australia West Sonya Hartnett/ Laureate 2008 Austria Austrian Section of IBBY Büchereiverband Österreichs (BVÖ) Christine Nöstlinger / Laureate 2003 THE ASTRID LINDGREN MEMORIAL AWARD Swedish Arts CouncilPO Box 27215SE-102 53 StockholmVisit Borgvägen 1-5, Stockholm Phone +46 (0)8-519 264 00E-mail [email protected]/en Azerbaijan Republic Children’s Library named after Firidun bay Kocharli Translation Centre under the Cabinet of Ministers of the Republic of Azerbaijan Union of Azerbaijani Writers Belarus Belarus Writers Association National Library of Belarus Belgium Belgian Section of IBBY (Flemish Branch) Belgian Section of IBBY (French Branch) Kitty Crowther / Laureate 2010 Muntpunt Bibliotheek Society of Children’s Book Writers and Illustrators, Belgium Vlaamse Illustratoren Club Vlaamse Vereniging voor Bibliotheek, Archief -

Guía De Libros Infantiles Y Juveniles México 2019

secretaría La Guía de libros infantiles y juveniles ibby México 2019 El agua es la tinta de cultura contiene breves reseñas de los libros recomendados que escribe la poesía por nuestro Comité Lector, clasificadas por etapas de la vida. lectoras; información sobre editoriales, librerías y Alexandra Cousteau bibliotecas; así como algunos datos sobre los principales premios internacionales de literatura infantil y juvenil. IBBY México guía de libros [email protected] www.ibbymexico.org.mx tiles y juveniles infan IBBY méxico 2019 2019 @ibbymexico México @IB xico BYmexico @ibbyme IBBY Guía de libros infantiles y juveniles y juveniles infantiles Guía de libros guía de libros infantiles y juveniles IBBY méxico 2019 Guía de libros infantiles y juveniles ibby México 2019 Primera edición, octubre de 2018 Coedición: guía de libros Asociación para Leer, Escuchar, Escribir y Recrear, A. C. / Secretaría de Cultura Dirección General de Publicaciones D. R. © 2018, Asociación para Leer, Escuchar, Escribir y Recrear, A. C. infantiles y juveniles Goya 54, Col. Mixcoac, Deleg. Benito Juárez, C. P. 03920, Ciudad de México 5563 1435, 5211 0492, 5211 0427 y 5211 9445 www.ibbymexico.org.mx [email protected] ibby méxico 2019 D. R. © 2018, de la presente edición Secretaría de Cultura María Cristina Vargas de la Mora Dirección General de Publicaciones Avenida Paseo de la Reforma 175, Col. Cuauhtémoc, C. P. 06500, Ciudad de México Coordinadora www.cultura.gob.mx Lectura y elaboración de reseñas: Comité Lector de ibby México Arnoldo Jesús Comparán Lara, Laura Cueto Sánchez, Verónica Juárez Campos, Abril G. Karera, Daniel González Maraver, Alberto Partida Coéllar, María Esther Pérez Feria, Lorena Rodríguez Barrera, Juan Carlos Rosas Ramírez e Ilana Wolff Hirsch. -

The Read-Aloud Collection Introduction

The Read-Aloud Collection Introduction Dear Parents and Educators, Bring Me A Book™ Hong Kong is a non-profit organization dedicated to promoting reading aloud to children. In the course of our work with parents, teachers and librarians, we are often asked to recommend books to get families and classrooms started. What you now hold in your hands is a home-grown guide, for your reference the next time you visit a library or bookstore. We have compiled a collection of the best books for reading aloud, from birth to teenage years. Reading together is an activity to be enjoyed as soon as children are born, and certainly should not end when they become independent readers. Reading aloud to children develops their language and literacy skills. It also paves the way for a lifelong love of reading as well as a lifelong love of learning. Most importantly, it helps to strengthen the parent-child bond; and a stable, loving relationship with your child is the best determinant for his or her future success and happiness in school and in life. In “The First 100 Books”, we have selected quality read-aloud books for babies and toddlers that can be enjoyed over and over. If your child has a particular area of interest, or you have life lessons you wish to impart, then look no further than our thematic guide, “Picture Books to Share”. For older children, we suggest “Chapter Books to Share”, and provide the ISBN for illustrated or read-aloud versions of these classic and contemporary stories. A heartfelt thanks to our other committee members for their valuable time and invaluable insight into this guide: BMABHK founder Su Chen, prominent children’s book historian Leonard Marcus, renowned librarian Jeffrey Comer, literacy specialist Diane Frankenstein, children’s book author Christina Matula-Häkli, BMABHK board governor Gweneth Rehnborg and BMABHK executive director Pia Wong. -

Changing Images of Family Postcolonial Young Adult Literature

2007 VOL 45, NO. 2 Changing images of family Postcolonial young adult literature in India Children’s literature in Mexico New forms of the Arcadian motif The Oxford Encyclopaedia of Children’s Literature Golden labels in BrBrazilazil The Journal of IBBY,the International Board on Books for Young People Editors: Valerie Coghlan and Siobhán Parkinson Address for submissions and other editorial correspondence: [email protected] and [email protected] Bookbird’s editorial office is supported by the Church of Ireland College of Education, Dublin, Ireland. Editorial Review Board: Sandra Beckett (Canada), Nina Christensen (Denmark), Penni Cotton (UK), Hans-Heino Ewers (Germany), Jeffrey Garrett (USA), Elwyn Jenkins (South Africa),Ariko Kawabata (Japan), Kerry Mallan (Australia), Maria Nikolajeva (Sweden), Jean Perrot (France), Kimberley Reynolds (UK), Mary Shine Thompson (Ireland), Victor Watson (UK), Jochen Weber (Germany) Guest reviewer for this issue: Claudia Söffner Board of Bookbird, Inc.: Joan Glazer (USA), President; Ellis Vance (USA),Treasurer;Alida Cutts (USA), Secretary;Ann Lazim (UK); Elda Nogueira (Brazil) Cover image: By Jutta Bauer from Christine Nöstlinger’s Einen Vater hab ich auch, reproduced by kind permission of the publishers, Beltz & Gelberg (Weinheim and Basel) Production: Design and layout by Oldtown Design, Dublin ([email protected]) Copyedited and proofread by Antoinette Walker Printed in Canada by Transcontinental Bookbird:A Journal of International Children’s Literature (ISSN 0006-7377) is a refereed journal published quarterly by IBBY,the International Board on Books for Young People, Nonnenweg 12 Postfach, CH-4003 Basel, Switzerland, tel. +4161 272 29 17 fax: +4161 272 27 57 email: [email protected] <www.ibby.org>. -

Selección Y Uso De Libros Para Lectores Iniciales. Guía Para La Educación Parvularia 1 PRESENTACIÓN Pag.4

Selección y uso de libros para lectores iniciales. Guía para la educación parvularia 1 PRESENTACIÓN Pag.4 2 CONCEPTOS ASOCIADOS A Pag.7 LOS LIBROS 5 RESEÑAS Y CARACTERIZACIÓN SEGÚN CRITERIOS Pag.47 PEDAGÓGICOS CRÉDITOS 3 REPERTORIO Y Pag.27 CLASIFICACIÓN 6 ORIENTACIONES Autoras Pag.87 PEDAGÓGICAS Gabriela Barra González Susana Mendive Criado 4 CRITERIOS PEDAGÓGICOS Maili Ow González Pag.39 PARA LA SELECCIÓN DE OBRAS Ayudante de proyecto Derechos Reservados Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile Valentina Strancar Muñoz Inscripción Nº297.160. 7 BIBLIOGRAFÍA Pag.111 Ilustraciones y diseño gráfico La presente guía utiliza de manera inclusiva Roxana Llaupe Ramírez palabras como “niño”, “lector”, “educador”, “adulto”, “mediador” y sus respectivos plu- Santiago, 2018. rales para referirse a hombres y mujeres, de manera de prevenir la saturación gráfica que conlleva el uso del o/a, os/as y los/las. ÍNDICE 4 5 Cada libro posee una multiplicidad de que ocurren durante el juego libre del niño, o cuando tanto en formación como en servicio, formadores de las bases curriculares de educación parvularia (MINEDUC, Este documento ha sido características atractivas y beneficiosas para el comparten una conversación durante la comida educadoras y técnicos en párvulos, directores de jardines 2018). En cambio, si el objetivo es conocer más en detalle diseñado tanto en versión desarrollo de los niños. Por un lado, los libros (Strasser, Darricades, Mendive & Barra, 2018). infantiles, padres y madres; quienes deciden qué libros el repertorio de libros seleccionado, el capítulo 5 permite impresa como electrónica. contienen características simbólicas y materiales se compran para bibliotecas públicas, de aula, de barrio conocer una breve reseña y su clasificación de acuerdo Pese a lo anterior, se ha constatado que la lectura que han sido diseñadas para la audiencia infantil, o en servicios de atención a niños (ej. -

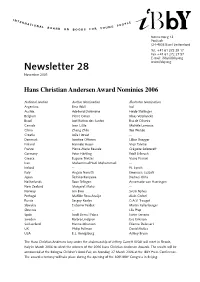

Newsletter 28, November 2005

Nonnenweg 12 Postfach CH-4003 Basel Switzerland Tel. +41 61 272 29 17 Fax +41 61 272 27 57 E-mail: [email protected] www.ibby.org Newsletter 28 November 2005 Hans Christian Andersen Award Nominies 2006 National Section Author Nomination Illustrator Nomination Argentina Ema Wolf Isol Austria Adelheid Dahiméne Heide Stöllinger Belgium Pierre Coran Klaas Verplancke Brazil Joel Rufino dos Santos Rui de Oliveira Canada Jean Little Michèle Lemieux China Zhang Zhilu Tao Wenjie Croatia Joˇza Horvat -- Denmark Josefine Ottesen Lillian Brøgger Finland Hannele Huovi Virpi Talvitie France Pierre-Marie Beaude Grégoire Solotareff Germany Peter Härtling Wolf Erlbruch Greece Eugene Trivizas Vasso Psaraki Iran Mohammad Hadi Mohammadi -- Ireland -- P.J. Lynch Italy Angela Nanetti Emanuele Luzzati Japan Toshiko Kanzawa Daihaci Ohta Netherlands Toon Tellegen Annemarie van Haeringen New Zealand Margaret Mahy -- Norway Jon Ewo Svein Nyhus Portugal Matilde Rosa Araújo Alain Corbel Russia Sergey Kozlov G.A.V. Traugot Slovakia L’ubomir Feldek Martin Kellenberger Slovenia -- Lila Prap Spain Jordi Sierra i Fabra Javier Serrano Sweden Barbro Lindgren Eva Eriksson Switzerland Hanna Johansen Etienne Delessert UK Philip Pullman David McKee USA E.L. Konigsburg Ashley Bryan The Hans Christian Andersen Jury under the chairmanship of Jeffrey Garrett (USA) will meet in Fiesole, Italy in March 2006 to select the winners of the 2006 Hans Christian Andersen Awards. The results will be announced at the Bologna Children’s Book Fair, on Monday, 27 March 2006 at the IBBY Press Conference. The award ceremony will take place during the opening of the 30th IBBY Congress in Beijing. IBBY Tsunami Appeal Hungarian Illustrators.