Mimics and Chameleons in Motor Neurone Disease

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Isolated Brachialis Muscle Atrophy

A Case Report & Literature Review Isolated Brachialis Muscle Atrophy John W. Karl, MD, MPH, Michael T. Krosin, MD, and Robert J. Strauch, MD or sensory complaints. His medical history was otherwise Abstract unremarkable. Physical examination revealed obvious wast- Isolated brachialis muscle atrophy, a rare entity with ing of the right brachialis muscle, most notable on the lateral few reported cases in the literature, is explained by a aspect of the distal arm (Figures 1, 2A, 2B). His biceps muscle variety of etiologies. We present a case of unilateral, was functioning with full strength and had a normal bulk. He isolated brachialis muscle atrophy that likely resulted had a normal range of active and passive motion, including from neuralgic amyotrophy. full extension and flexion of both elbows, as well as complete Figure 1. Frontal view of both arms: note the brachialis atrophy solated brachialis muscle atrophy has been rarely reported. (solid arrow) on the right side, although the biceps contracts well. Among the few cases in the literature, 1 was attributed I to a presumed compartment syndrome,1 1 to a displaced clavicle fracture,2 and 3 to neuralgic amyotrophy.3,4 We pres- ent a case of isolated brachialis muscle atrophy of unknown etiology, the presentation of which is consistent with neuralgic amyotrophy, also known as Parsonage-Turner syndrome or brachial plexitis. The patient provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report. AJO Case Report A 37-year-old right-handed highway worker presented for eval- uation of right-arm muscle atrophy. One year earlier, while lift- ing heavy bags at work, he felt a painful strain in his right arm, although there was no bruising or swelling. -

Whole Exome Sequencing Gene Package Intellectual Disability, Version 9.1, 31-1-2020

Whole Exome Sequencing Gene package Intellectual disability, version 9.1, 31-1-2020 Technical information DNA was enriched using Agilent SureSelect DNA + SureSelect OneSeq 300kb CNV Backbone + Human All Exon V7 capture and paired-end sequenced on the Illumina platform (outsourced). The aim is to obtain 10 Giga base pairs per exome with a mapped fraction of 0.99. The average coverage of the exome is ~50x. Duplicate and non-unique reads are excluded. Data are demultiplexed with bcl2fastq Conversion Software from Illumina. Reads are mapped to the genome using the BWA-MEM algorithm (reference: http://bio-bwa.sourceforge.net/). Variant detection is performed by the Genome Analysis Toolkit HaplotypeCaller (reference: http://www.broadinstitute.org/gatk/). The detected variants are filtered and annotated with Cartagenia software and classified with Alamut Visual. It is not excluded that pathogenic mutations are being missed using this technology. At this moment, there is not enough information about the sensitivity of this technique with respect to the detection of deletions and duplications of more than 5 nucleotides and of somatic mosaic mutations (all types of sequence changes). HGNC approved Phenotype description including OMIM phenotype ID(s) OMIM median depth % covered % covered % covered gene symbol gene ID >10x >20x >30x A2ML1 {Otitis media, susceptibility to}, 166760 610627 66 100 100 96 AARS1 Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease, axonal, type 2N, 613287 601065 63 100 97 90 Epileptic encephalopathy, early infantile, 29, 616339 AASS Hyperlysinemia, -

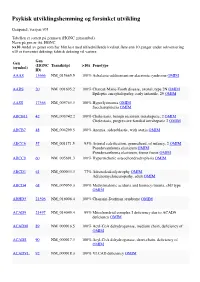

Psykisk Utviklingshemming Og Forsinket Utvikling

Psykisk utviklingshemming og forsinket utvikling Genpanel, versjon v03 Tabellen er sortert på gennavn (HGNC gensymbol) Navn på gen er iht. HGNC >x10 Andel av genet som har blitt lest med tilfredstillende kvalitet flere enn 10 ganger under sekvensering x10 er forventet dekning; faktisk dekning vil variere. Gen Gen (HGNC Transkript >10x Fenotype (symbol) ID) AAAS 13666 NM_015665.5 100% Achalasia-addisonianism-alacrimia syndrome OMIM AARS 20 NM_001605.2 100% Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease, axonal, type 2N OMIM Epileptic encephalopathy, early infantile, 29 OMIM AASS 17366 NM_005763.3 100% Hyperlysinemia OMIM Saccharopinuria OMIM ABCB11 42 NM_003742.2 100% Cholestasis, benign recurrent intrahepatic, 2 OMIM Cholestasis, progressive familial intrahepatic 2 OMIM ABCB7 48 NM_004299.5 100% Anemia, sideroblastic, with ataxia OMIM ABCC6 57 NM_001171.5 93% Arterial calcification, generalized, of infancy, 2 OMIM Pseudoxanthoma elasticum OMIM Pseudoxanthoma elasticum, forme fruste OMIM ABCC9 60 NM_005691.3 100% Hypertrichotic osteochondrodysplasia OMIM ABCD1 61 NM_000033.3 77% Adrenoleukodystrophy OMIM Adrenomyeloneuropathy, adult OMIM ABCD4 68 NM_005050.3 100% Methylmalonic aciduria and homocystinuria, cblJ type OMIM ABHD5 21396 NM_016006.4 100% Chanarin-Dorfman syndrome OMIM ACAD9 21497 NM_014049.4 99% Mitochondrial complex I deficiency due to ACAD9 deficiency OMIM ACADM 89 NM_000016.5 100% Acyl-CoA dehydrogenase, medium chain, deficiency of OMIM ACADS 90 NM_000017.3 100% Acyl-CoA dehydrogenase, short-chain, deficiency of OMIM ACADVL 92 NM_000018.3 100% VLCAD -

Massive Indoor Cycling-Induced Rhabdomyolysis in a Patient With

CASE CoMMUNICATIONS IMAJ • VOL 14 • noveMber 2012 Massive Indoor Cycling-Induced Rhabdomyolysis in a Patient with Hereditary Neuropathy with Liability to Pressure Palsy Marganit Benish PhD1, Inna Zeitlin MD2, Dana Deshet MD2 and Yitzhak Beigel MD1,2 1Sackler Faculty of Medicine, Tel Aviv University, Ramat Aviv, Israel 2Department of Medicine D, Wolfson Medical Center, Holon, Israel profoundly decreased. Severe pain exercise-induced rhabdomyolysis, KEY WORDS: PATIENT DESCRIPTION and stiffness were observed when she hereditary neuropathy with liability A 21 year old female was hospitalized stretched both legs. She did not suffer to pressure palsy (HNPP), creatine kinase, indoor cycling, “spinning,” in December 2011 because of pain from any other medical condition and myoglobin and profound weakness in her thighs had no history of recent exposure to IMAJ 2012; 14: 712-714 rendering her unable to walk, and tea- medications, vaccines, alcohol drinking, colored urine. The muscular symptoms or any signs and symptoms of a viral had begun 5 days prior to her admis- infection. Laboratory results showed a sion, starting immediately after she had CK level of 132,170 U/L (range < 10–145 participated, for the first time in her U/L) and increased transaminase levels habdomyolysis is a condition charac- life, in an indoor-cycling class (“spin- (alanine transaminase 280 U/L (< 3–31 R terized by extended myolysis, marked ning”) lasting 45 minutes. The color U/L), aspartate transaminase 1256 U/L elevation of serum creatine kinase and of her urine changed and prompted (< 3–32 U/L) [Table], serum sodium myoglobinuria. Weakness, myalgia, and her to immediately seek medical care. -

Iatrogenic Neuromuscular Disorders

Iatrogenic Neuromuscular Disorders Peter D. Donofrio, MD Anthony A. Amato, MD James F. Howard, Jr., MD Charles F. Bolton, MD, FRCP(C) 2009 COURSE G AANEM 56th Annual Meeting San Diego, California Copyright © October 2009 American Association of Neuromuscular & Electrodiagnostic Medicine 2621 Superior Drive NW Rochester, MN 55901 Printed by Johnson Printing Company, Inc. ii Iatrogenic Neuromuscular Disorders Faculty Anthony A. Amato, MD Charles F. Bolton, MD, FRCP(C) Department of Neurology Faculty Brigham and Women’s Hospital Department of Medicine Division of Neurology Harvard Medical School Queen’s University Boston, Massachusetts Kingston, Ontario, Canada Dr. Amato is the vice-chairman of the department of neurology and the Dr. Bolton was born in Outlook, Saskatchewan, Canada. He received director of the neuromuscular division and clinical neurophysiology labo- his medical degree from Queen’s University and trained in neurology ratory at Brigham and Women’s Hospital (BWH/MGH) in Boston. He is at the University Hospital, Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, Canada, and at also professor of neurology at Harvard Medical School. He is the director the Mayo Clinic. While at Mayo Clinic, he studied neuromuscular of the Partners Neuromuscular Medicine fellowship program. Dr. Amato disease under Dr. Peter Dyck, and electromyography under Dr. Edward is an author or co-author on over 150 published articles, chapters, and Lambert. Dr. Bolton has had academic appointments at the Universities books. He co-wrote the textbook Neuromuscular Disorders with Dr. Jim of Saskatchewan and Western Ontario, at the Mayo Clinic, and cur- Russell. He has been involved in clinical research trials involving patients rently at Queen’s University. -

P 2-92 Distal Type of Neuralgic Amyotrophy Presenting With

P 2-92 Distal Type of Neuralgic Amyotrophy Presenting with Multifocal Motor Neuropathy : A Case report Jung Ho Yang1*, Seung Hoon Han1† Hanyang University College of Medicine, Department of Rehabilitation Medicine1 Introduction A distal form of neuralgic amyotrophy in which weakness is limited to the forearm and hand muscles is rare and not explicitly mentioned in many neurological textbooks. We report a case that shows left hand motor weakness without any sensory symptom and diagnoses of distal type neuralgic amyotrophy. Case presentation Fifty eight-year-old male presented with nuchal pain with radiating pain to left upper extremity. On his first visit, he also showed general motor weakness of left upper extremity including shoulder and elbow. The symptoms started from 20 days earlier. Motor weakness of left hand and wrist was prominent with MRC grade 2 finger abductor and wrist extensor, respectively. Additionally, he had atrophy of left hand intrinsic muscles. However, there was no sensory abnormalities on left upper extremity. He had no specific past, personal, and family history on any muscle weakness. The patient underwent cervical spine magnetic resonance image to rule out cervical spinal cord injury or possibility of cervical radiculopathy. It showed disc space narrowing of multiple cervical intervertebral segments. Electrodiagnostic study was performed and it showed decreased amplitude of left median, ulnar, and radial compound muscle action potentials recording at Abductor pollicis brevis, Abductor digiti minimi, and Extensor indicis proprius respectively. There was no abnormality of sensory nerve action potentials and median F- wave. On needle electromyography, abnormal spontaneous activities were found in left Abductor pollicis brevis, Abductor digiti minimi, Extensor carpi radialis longus, First dorsal interosseous, Flexor carpi ulnaris, Triceps, and Extensor indicis proprius muscles. -

Whole Exome Sequencing Gene Package Skeletal Dysplasia, Version 2.1, 31-1-2020

Whole Exome Sequencing Gene package Skeletal Dysplasia, Version 2.1, 31-1-2020 Technical information DNA was enriched using Agilent SureSelect DNA + SureSelect OneSeq 300kb CNV Backbone + Human All Exon V7 capture and paired-end sequenced on the Illumina platform (outsourced). The aim is to obtain 10 Giga base pairs per exome with a mapped fraction of 0.99. The average coverage of the exome is ~50x. Duplicate and non-unique reads are excluded. Data are demultiplexed with bcl2fastq Conversion Software from Illumina. Reads are mapped to the genome using the BWA-MEM algorithm (reference: http://bio-bwa.sourceforge.net/). Variant detection is performed by the Genome Analysis Toolkit HaplotypeCaller (reference: http://www.broadinstitute.org/gatk/). The detected variants are filtered and annotated with Cartagenia software and classified with Alamut Visual. It is not excluded that pathogenic mutations are being missed using this technology. At this moment, there is not enough information about the sensitivity of this technique with respect to the detection of deletions and duplications of more than 5 nucleotides and of somatic mosaic mutations (all types of sequence changes). HGNC approved Phenotype description including OMIM phenotype ID(s) OMIM median depth % covered % covered % covered gene symbol gene ID >10x >20x >30x ABCC9 Atrial fibrillation, familial, 12, 614050 601439 65 100 100 95 Cardiomyopathy, dilated, 1O, 608569 Hypertrichotic osteochondrodysplasia, 239850 ACAN Short stature and advanced bone age, with or without early-onset osteoarthritis -

Diabetic Amyotrophy: a Report of Two Cases John Peacock

Henry Ford Hospital Medical Journal Volume 12 | Number 1 Article 14 3-1964 Diabetic Amyotrophy: A Report Of Two Cases John Peacock Raul Calderon Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.henryford.com/hfhmedjournal Part of the Life Sciences Commons, Medical Specialties Commons, and the Public Health Commons Recommended Citation Peacock, John and Calderon, Raul (1964) "Diabetic Amyotrophy: A Report Of Two Cases," Henry Ford Hospital Medical Bulletin : Vol. 12 : No. 1 , 135-140. Available at: https://scholarlycommons.henryford.com/hfhmedjournal/vol12/iss1/14 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Henry Ford Health System Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Henry Ford Hospital Medical Journal by an authorized editor of Henry Ford Health System Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Henry Ford Hosp. Med. Bull. Vol. 12, March, 1964 DIABETIC AMYOTROPHY A Report of Two Cases loHN PEACOCK, M.D. AND RAUL CALDERON, M.D. DIABETIC AMYOTROPHY is a syndrome of bilateral, asymmetrical, proximal muscle weakness particularly in the lower extremities. The syndrome is associated with variable diffuse pain and atrophy and occasionally fasciculations with weight loss and most commonly seen in elderly diabetic males.' The first symptom is a gradual muscular weakness and wasting in the legs, the muscles affected being in anatomi cal proximity (other muscles of the same nervous supply may be spared entirely). Usually the pelvic girdle musculature is affected first but eventually global involve ment of the leg may make the patient bedridden. Occasionally, muscles of the trunk and upper limb may be affected. -

The Forearm Ischaemic Work Test - Hazardous to Mcardle Patients?

J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry: first published as 10.1136/jnnp.45.12.1144 on 1 December 1982. Downloaded from Journal ofNeurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry 1982;45:1144-1146 Short report The forearm ischaemic work test - hazardous to McArdle patients? HM MEINCK,* HH GOEBEL,t KW RUMPF,4 H KAISER,4 P NEUMANN§ From the Departments of Clinical Neurophysiology, * Neuropathology, t Medicinet and Nuclear Medicine,§ University of Gottingen, Gottingen, Federal Republic of Germany SUMMARY A 57-year-old patient suffering from late-onset McArdle's disease developed myoglobinaemia, massive myoglobinuria and marked serum creatine kinase elevation subsequent to a routinely performed forearm ischaemic work test. Twenty hours after the test, enhancement of99mTc methylene-diphosphonate activity was demonstrated exclusively in the tested forearm. It is concluded that the forearm ischaemic work test is potentially hazardous to McArdle patients, as it might induce myoglobinuria sufficient to result in acute myoglobinuric renal failure. The forearm ischaemic work test is established as a increased, and serum creatine kinase and creatinine levels guest. Protected by copyright. useful tool for differentiating between myopathies remained high. Serum lactate dehydrogenase (normally with and without defects of anaerobic glycogenolysis below 195 gi/l) was observed between values of 163 and 263 and glycolysis. So far no dangerous effects of this test I/l. Repeated ECGs and tests of left ventricular function have We report a case of late-onset (measured scintigraphically by means of gated blood pool been described. imaging) were normal. McArdle's disease' (glycogenosis V2), in which Neurological examination revealed atrophy and paresis massive myoglobinaemia and myoglobinuria (degrees III to IV on the MRC scale) of the shoulder girdle developed subsequent to this test. -

Characterisation of Pain in People with Hereditary Neuropathy with Liability to Pressure Palsy

Characterisation of pain in people with hereditary neuropathy with liability to pressure palsy Darren Beales1 * (Orcid: 0000-0002-7176-4644) Robyn Fary1 Cameron Little1 Shruti Nambiar1 Hakon Sveinall1 Yen Leng Yee1 Brigitte Tampin1,2,3 Tim Mitchell1 1 School of Physiotherapy and Exercise Science, Curtin University. GPO Box U1987, Perth, Western Australia, Australia 6845 2Physiotherapy Department, Sir Charles Gairdner Hospital, Hospital Ave, Nedlands, Western Australia, 6009, Australia 3Faculty of Business Management and Social Sciences, Hochschule Osnabrück, University of Applied Sciences, Caprivistr. 30A, 49076 Osnabrück, Germany * Corresponding Author Dr Darren Beales. School of Physiotherapy and Exercise Science, Curtin University. GPO Box U1987, Perth, Western Australia 6845. Tel.: +61 8 9266 4644 Fax: +61 8 9266 3699 E-mail: [email protected] 1 Abstract Hereditary neuropathy with liability to pressure palsy (HNPP) has historically been considered a pain free condition, though some people with HNPP also complain of pain. This study characterised persistent pain in people with HNPP. Participants provided cross- sectional demographic data, information on the presence of neurological and persistent pain symptoms, and the degree to which these interfered with daily life. The painDETECT and Central Sensitization Inventory questionnaires were used to indicate potential neuropathic, central sensitisation and musculoskeletal (nociceptive) pain mechanisms. Additionally, participants were asked if they thought that pain was related to/part of HNPP. 32/43 (74%) subjects with HNPP had persistent pain and experiencing this pain in the last week. Of those with pain, 24 (75%) were likely to have neuropathic pain and 27 (84%) were likely to have central sensitisation. All 32 participants felt that their pain could be related to/part of their HNPP. -

Differentiating Lower Motor Neuron Syndromes

Neuromuscular J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry: first published as 10.1136/jnnp-2016-313526 on 21 December 2016. Downloaded from REVIEW Differentiating lower motor neuron syndromes Nidhi Garg,1 Susanna B Park,1 Steve Vucic,2 Con Yiannikas,3 Judy Spies,1 James Howells,1 William Huynh,1,4 José M Matamala,1 Arun V Krishnan,4 John D Pollard,1 David R Cornblath,5 Mary M Reilly,6 Matthew C Kiernan1 ► Additional material is ABSTRACT MND from other relatively indolent conditions, published online only. To view Lower motor neuron (LMN) syndromes typically present such as SMA and immune neuropathies. The please visit the journal online (http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/ with muscle wasting and weakness and may arise from pattern of weakness should be documented, includ- jnnp-2016-313526). pathology affecting the distal motor nerve up to the level ing (1) symmetry versus asymmetry, (2) proximal of the anterior horn cell. A variety of hereditary causes versus distal involvement, (3) upper versus lower 1Brain and Mind Centre, Sydney are recognised, including spinal muscular atrophy, distal limb predominance and (4) presence versus absence Medical School, The University hereditary motor neuropathy and LMN variants of of bulbar involvement. Nerve conduction studies of Sydney, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia familial motor neuron disease. Recent genetic advances and electromyography (EMG) are essential to 2Departments of Neurology and have resulted in the identification of a variety of disease- confirm that the disorder is neurogenic and should Neurophysiology, -

Myopathy with Tubulin-Reactive Inclusions in Two Cats

Acta Neuropathol (2007) 114:537–542 DOI 10.1007/s00401-007-0217-6 CASE REPORT Myopathy with tubulin-reactive inclusions in two cats G. Diane Shelton · Beverly K. Sturges · Leslie A. Lyons · D. Colette Williams · Monica Aleman · Yun Jiang · Andrew P. Mizisin Received: 26 January 2007 / Revised: 5 March 2007 / Accepted: 6 March 2007 / Published online: 29 March 2007 © Springer-Verlag 2007 Abstract Many types of inclusions have been described Keywords Cats · Myopathy · Crystalline inclusions · in human myopathies including but not limited to nemaline Tubulin rod bodies, cylindrical spirals, tubular aggregates, cytoplas- mic bodies, reducing bodies, and Wngerprint bodies, and hyaline inclusions in myoWbrillar myopathy and inclusion Introduction body myositis. There are very few reports describing inclu- sions in spontaneously occurring myopathies in cats, and Inclusions described in human myopathies include nema- these reports are limited to nemaline rod myopathy. A line rod bodies, cylindrical spirals, tubular aggregates, cyto- myopathy with tubulin-reactive crystalline inclusions has plasmic bodies, reducing bodies, Wngerprint bodies, and recently been reported in a human patient with a clinical hyaline inclusions in myoWbrillar myopathy and inclusion presentation of myalgia and fatigue. Similarly, a myopathy body myositis [2]. These inclusions may be the primary with chronic, slowly progressive muscle weakness has been pathologic change as in myopathies associated with nema- identiWed here in two unrelated cats. Inclusions were the line rods, tubular aggregates or cylindrical spirals [9], or only pathological change in skeletal muscle biopsies and, may be associated with other myopathic abnormalities as in ultrastructurally, groups of crystalline structures were evi- myoWbrillar myopathy [11] and inclusion body myositis dent that had a subsarcolemmal or central location, rhom- [1].