Brachial Plexopathies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Isolated Brachialis Muscle Atrophy

A Case Report & Literature Review Isolated Brachialis Muscle Atrophy John W. Karl, MD, MPH, Michael T. Krosin, MD, and Robert J. Strauch, MD or sensory complaints. His medical history was otherwise Abstract unremarkable. Physical examination revealed obvious wast- Isolated brachialis muscle atrophy, a rare entity with ing of the right brachialis muscle, most notable on the lateral few reported cases in the literature, is explained by a aspect of the distal arm (Figures 1, 2A, 2B). His biceps muscle variety of etiologies. We present a case of unilateral, was functioning with full strength and had a normal bulk. He isolated brachialis muscle atrophy that likely resulted had a normal range of active and passive motion, including from neuralgic amyotrophy. full extension and flexion of both elbows, as well as complete Figure 1. Frontal view of both arms: note the brachialis atrophy solated brachialis muscle atrophy has been rarely reported. (solid arrow) on the right side, although the biceps contracts well. Among the few cases in the literature, 1 was attributed I to a presumed compartment syndrome,1 1 to a displaced clavicle fracture,2 and 3 to neuralgic amyotrophy.3,4 We pres- ent a case of isolated brachialis muscle atrophy of unknown etiology, the presentation of which is consistent with neuralgic amyotrophy, also known as Parsonage-Turner syndrome or brachial plexitis. The patient provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report. AJO Case Report A 37-year-old right-handed highway worker presented for eval- uation of right-arm muscle atrophy. One year earlier, while lift- ing heavy bags at work, he felt a painful strain in his right arm, although there was no bruising or swelling. -

Whole Exome Sequencing Gene Package Intellectual Disability, Version 9.1, 31-1-2020

Whole Exome Sequencing Gene package Intellectual disability, version 9.1, 31-1-2020 Technical information DNA was enriched using Agilent SureSelect DNA + SureSelect OneSeq 300kb CNV Backbone + Human All Exon V7 capture and paired-end sequenced on the Illumina platform (outsourced). The aim is to obtain 10 Giga base pairs per exome with a mapped fraction of 0.99. The average coverage of the exome is ~50x. Duplicate and non-unique reads are excluded. Data are demultiplexed with bcl2fastq Conversion Software from Illumina. Reads are mapped to the genome using the BWA-MEM algorithm (reference: http://bio-bwa.sourceforge.net/). Variant detection is performed by the Genome Analysis Toolkit HaplotypeCaller (reference: http://www.broadinstitute.org/gatk/). The detected variants are filtered and annotated with Cartagenia software and classified with Alamut Visual. It is not excluded that pathogenic mutations are being missed using this technology. At this moment, there is not enough information about the sensitivity of this technique with respect to the detection of deletions and duplications of more than 5 nucleotides and of somatic mosaic mutations (all types of sequence changes). HGNC approved Phenotype description including OMIM phenotype ID(s) OMIM median depth % covered % covered % covered gene symbol gene ID >10x >20x >30x A2ML1 {Otitis media, susceptibility to}, 166760 610627 66 100 100 96 AARS1 Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease, axonal, type 2N, 613287 601065 63 100 97 90 Epileptic encephalopathy, early infantile, 29, 616339 AASS Hyperlysinemia, -

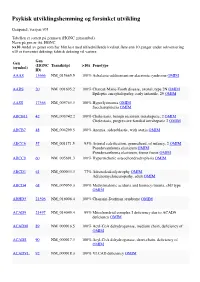

Psykisk Utviklingshemming Og Forsinket Utvikling

Psykisk utviklingshemming og forsinket utvikling Genpanel, versjon v03 Tabellen er sortert på gennavn (HGNC gensymbol) Navn på gen er iht. HGNC >x10 Andel av genet som har blitt lest med tilfredstillende kvalitet flere enn 10 ganger under sekvensering x10 er forventet dekning; faktisk dekning vil variere. Gen Gen (HGNC Transkript >10x Fenotype (symbol) ID) AAAS 13666 NM_015665.5 100% Achalasia-addisonianism-alacrimia syndrome OMIM AARS 20 NM_001605.2 100% Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease, axonal, type 2N OMIM Epileptic encephalopathy, early infantile, 29 OMIM AASS 17366 NM_005763.3 100% Hyperlysinemia OMIM Saccharopinuria OMIM ABCB11 42 NM_003742.2 100% Cholestasis, benign recurrent intrahepatic, 2 OMIM Cholestasis, progressive familial intrahepatic 2 OMIM ABCB7 48 NM_004299.5 100% Anemia, sideroblastic, with ataxia OMIM ABCC6 57 NM_001171.5 93% Arterial calcification, generalized, of infancy, 2 OMIM Pseudoxanthoma elasticum OMIM Pseudoxanthoma elasticum, forme fruste OMIM ABCC9 60 NM_005691.3 100% Hypertrichotic osteochondrodysplasia OMIM ABCD1 61 NM_000033.3 77% Adrenoleukodystrophy OMIM Adrenomyeloneuropathy, adult OMIM ABCD4 68 NM_005050.3 100% Methylmalonic aciduria and homocystinuria, cblJ type OMIM ABHD5 21396 NM_016006.4 100% Chanarin-Dorfman syndrome OMIM ACAD9 21497 NM_014049.4 99% Mitochondrial complex I deficiency due to ACAD9 deficiency OMIM ACADM 89 NM_000016.5 100% Acyl-CoA dehydrogenase, medium chain, deficiency of OMIM ACADS 90 NM_000017.3 100% Acyl-CoA dehydrogenase, short-chain, deficiency of OMIM ACADVL 92 NM_000018.3 100% VLCAD -

Journal of Biomechanical Science and Engineering Researches on Biomechanical Properties and Models of Peripheral Nerves

Bulletin of the JSME Vol.12, No.1, 2017 Journal of Biomechanical Science and Engineering 【Review Paper】 Researches on biomechanical properties and models of peripheral nerves - a review Ming-Shaung JU*, Chou-Ching K. LIN** and Cheng-Tao CHANG* *Department of Mechanical Engineering, National Cheng Kung University 1 University Road, Tainan 701, Taiwan (R.O.C.) E-mail: [email protected] **Department of Neurology College of Medicine and University Hospital National Cheng Kung University 1 University Road, Tainan 701, Taiwan (R.O.C.) Received: 14 December 2016; Revised: 11 February 2017; Accepted: 6 March 2017 Abstract The biomechanics of peripheral nerve plays an important role in physiology of the healthy and pathology of the diseased such as the diabetic neuropathy, the cauda equine compression and the carpal tunnel syndrome. The other application is recent development of neural prostheses. The goal of this paper is to review researches done by members of Taiwanese Society of Biomechanics on the biomechanics of peripheral nerves in the past two decades. First, a brief introduction of the anatomy of peripheral nerve is given. Then experiment designs and mechanical models for testing the nerves are presented. The material properties ranged from linear elastic to nonlinear visco-elastic and scales ranged from organ level to tissue level are reviewed. Implications of these studies to clinical problems will be addressed and the challenges and future perspective on biomechanics of peripheral nerve are discussed. Key words: Biomechanics, Peripheral nerve, Review, Diabetic mellitus, Cauda equine 1. Introduction Nervous system plays an important role in the human body it can coordinate voluntary and involuntary actions of other tissues and sub-systems. -

Massive Indoor Cycling-Induced Rhabdomyolysis in a Patient With

CASE CoMMUNICATIONS IMAJ • VOL 14 • noveMber 2012 Massive Indoor Cycling-Induced Rhabdomyolysis in a Patient with Hereditary Neuropathy with Liability to Pressure Palsy Marganit Benish PhD1, Inna Zeitlin MD2, Dana Deshet MD2 and Yitzhak Beigel MD1,2 1Sackler Faculty of Medicine, Tel Aviv University, Ramat Aviv, Israel 2Department of Medicine D, Wolfson Medical Center, Holon, Israel profoundly decreased. Severe pain exercise-induced rhabdomyolysis, KEY WORDS: PATIENT DESCRIPTION and stiffness were observed when she hereditary neuropathy with liability A 21 year old female was hospitalized stretched both legs. She did not suffer to pressure palsy (HNPP), creatine kinase, indoor cycling, “spinning,” in December 2011 because of pain from any other medical condition and myoglobin and profound weakness in her thighs had no history of recent exposure to IMAJ 2012; 14: 712-714 rendering her unable to walk, and tea- medications, vaccines, alcohol drinking, colored urine. The muscular symptoms or any signs and symptoms of a viral had begun 5 days prior to her admis- infection. Laboratory results showed a sion, starting immediately after she had CK level of 132,170 U/L (range < 10–145 participated, for the first time in her U/L) and increased transaminase levels habdomyolysis is a condition charac- life, in an indoor-cycling class (“spin- (alanine transaminase 280 U/L (< 3–31 R terized by extended myolysis, marked ning”) lasting 45 minutes. The color U/L), aspartate transaminase 1256 U/L elevation of serum creatine kinase and of her urine changed and prompted (< 3–32 U/L) [Table], serum sodium myoglobinuria. Weakness, myalgia, and her to immediately seek medical care. -

Iatrogenic Neuromuscular Disorders

Iatrogenic Neuromuscular Disorders Peter D. Donofrio, MD Anthony A. Amato, MD James F. Howard, Jr., MD Charles F. Bolton, MD, FRCP(C) 2009 COURSE G AANEM 56th Annual Meeting San Diego, California Copyright © October 2009 American Association of Neuromuscular & Electrodiagnostic Medicine 2621 Superior Drive NW Rochester, MN 55901 Printed by Johnson Printing Company, Inc. ii Iatrogenic Neuromuscular Disorders Faculty Anthony A. Amato, MD Charles F. Bolton, MD, FRCP(C) Department of Neurology Faculty Brigham and Women’s Hospital Department of Medicine Division of Neurology Harvard Medical School Queen’s University Boston, Massachusetts Kingston, Ontario, Canada Dr. Amato is the vice-chairman of the department of neurology and the Dr. Bolton was born in Outlook, Saskatchewan, Canada. He received director of the neuromuscular division and clinical neurophysiology labo- his medical degree from Queen’s University and trained in neurology ratory at Brigham and Women’s Hospital (BWH/MGH) in Boston. He is at the University Hospital, Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, Canada, and at also professor of neurology at Harvard Medical School. He is the director the Mayo Clinic. While at Mayo Clinic, he studied neuromuscular of the Partners Neuromuscular Medicine fellowship program. Dr. Amato disease under Dr. Peter Dyck, and electromyography under Dr. Edward is an author or co-author on over 150 published articles, chapters, and Lambert. Dr. Bolton has had academic appointments at the Universities books. He co-wrote the textbook Neuromuscular Disorders with Dr. Jim of Saskatchewan and Western Ontario, at the Mayo Clinic, and cur- Russell. He has been involved in clinical research trials involving patients rently at Queen’s University. -

P 2-92 Distal Type of Neuralgic Amyotrophy Presenting With

P 2-92 Distal Type of Neuralgic Amyotrophy Presenting with Multifocal Motor Neuropathy : A Case report Jung Ho Yang1*, Seung Hoon Han1† Hanyang University College of Medicine, Department of Rehabilitation Medicine1 Introduction A distal form of neuralgic amyotrophy in which weakness is limited to the forearm and hand muscles is rare and not explicitly mentioned in many neurological textbooks. We report a case that shows left hand motor weakness without any sensory symptom and diagnoses of distal type neuralgic amyotrophy. Case presentation Fifty eight-year-old male presented with nuchal pain with radiating pain to left upper extremity. On his first visit, he also showed general motor weakness of left upper extremity including shoulder and elbow. The symptoms started from 20 days earlier. Motor weakness of left hand and wrist was prominent with MRC grade 2 finger abductor and wrist extensor, respectively. Additionally, he had atrophy of left hand intrinsic muscles. However, there was no sensory abnormalities on left upper extremity. He had no specific past, personal, and family history on any muscle weakness. The patient underwent cervical spine magnetic resonance image to rule out cervical spinal cord injury or possibility of cervical radiculopathy. It showed disc space narrowing of multiple cervical intervertebral segments. Electrodiagnostic study was performed and it showed decreased amplitude of left median, ulnar, and radial compound muscle action potentials recording at Abductor pollicis brevis, Abductor digiti minimi, and Extensor indicis proprius respectively. There was no abnormality of sensory nerve action potentials and median F- wave. On needle electromyography, abnormal spontaneous activities were found in left Abductor pollicis brevis, Abductor digiti minimi, Extensor carpi radialis longus, First dorsal interosseous, Flexor carpi ulnaris, Triceps, and Extensor indicis proprius muscles. -

Whole Exome Sequencing Gene Package Skeletal Dysplasia, Version 2.1, 31-1-2020

Whole Exome Sequencing Gene package Skeletal Dysplasia, Version 2.1, 31-1-2020 Technical information DNA was enriched using Agilent SureSelect DNA + SureSelect OneSeq 300kb CNV Backbone + Human All Exon V7 capture and paired-end sequenced on the Illumina platform (outsourced). The aim is to obtain 10 Giga base pairs per exome with a mapped fraction of 0.99. The average coverage of the exome is ~50x. Duplicate and non-unique reads are excluded. Data are demultiplexed with bcl2fastq Conversion Software from Illumina. Reads are mapped to the genome using the BWA-MEM algorithm (reference: http://bio-bwa.sourceforge.net/). Variant detection is performed by the Genome Analysis Toolkit HaplotypeCaller (reference: http://www.broadinstitute.org/gatk/). The detected variants are filtered and annotated with Cartagenia software and classified with Alamut Visual. It is not excluded that pathogenic mutations are being missed using this technology. At this moment, there is not enough information about the sensitivity of this technique with respect to the detection of deletions and duplications of more than 5 nucleotides and of somatic mosaic mutations (all types of sequence changes). HGNC approved Phenotype description including OMIM phenotype ID(s) OMIM median depth % covered % covered % covered gene symbol gene ID >10x >20x >30x ABCC9 Atrial fibrillation, familial, 12, 614050 601439 65 100 100 95 Cardiomyopathy, dilated, 1O, 608569 Hypertrichotic osteochondrodysplasia, 239850 ACAN Short stature and advanced bone age, with or without early-onset osteoarthritis -

Diabetic Amyotrophy: a Report of Two Cases John Peacock

Henry Ford Hospital Medical Journal Volume 12 | Number 1 Article 14 3-1964 Diabetic Amyotrophy: A Report Of Two Cases John Peacock Raul Calderon Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.henryford.com/hfhmedjournal Part of the Life Sciences Commons, Medical Specialties Commons, and the Public Health Commons Recommended Citation Peacock, John and Calderon, Raul (1964) "Diabetic Amyotrophy: A Report Of Two Cases," Henry Ford Hospital Medical Bulletin : Vol. 12 : No. 1 , 135-140. Available at: https://scholarlycommons.henryford.com/hfhmedjournal/vol12/iss1/14 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Henry Ford Health System Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Henry Ford Hospital Medical Journal by an authorized editor of Henry Ford Health System Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Henry Ford Hosp. Med. Bull. Vol. 12, March, 1964 DIABETIC AMYOTROPHY A Report of Two Cases loHN PEACOCK, M.D. AND RAUL CALDERON, M.D. DIABETIC AMYOTROPHY is a syndrome of bilateral, asymmetrical, proximal muscle weakness particularly in the lower extremities. The syndrome is associated with variable diffuse pain and atrophy and occasionally fasciculations with weight loss and most commonly seen in elderly diabetic males.' The first symptom is a gradual muscular weakness and wasting in the legs, the muscles affected being in anatomi cal proximity (other muscles of the same nervous supply may be spared entirely). Usually the pelvic girdle musculature is affected first but eventually global involve ment of the leg may make the patient bedridden. Occasionally, muscles of the trunk and upper limb may be affected. -

685 Mechanisms and Controllers of Eccrine Sweating in Humans Manabu Shiba

[Frontiers in Bioscience S2, 685-696, January 1, 2010] Mechanisms and controllers of eccrine sweating in humans Manabu Shibasaki1, Craig G. Crandall2,3 1Department of Environmental and Life Sciences, Nara Women's University Graduate School of Humanities and Sciences, Nara Japan, 2Department of Internal Medicine, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, TX, 3Institute for Exercise and Environmental Medicine, Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital of Dallas, TX TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Abstract 2. Introduction and historical perspective 3. Neural pathway from the brain to sweat gland 4. Non-thermal modulators of sweat rate 4.1. Effect of exercise in modulating sweat rate 4.2. Effect of baroreceptors in modulating sweat rate 4.3. Effect of body fluid status and osmolality on sweat rate 5. Summary 6. Acknowledgement 7. References 1. ABSTRACT 2. INTRODUCTION AND HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE Human body temperature is regulated within a very narrow range. When exposed to hyperthermic conditions, via Evaporative heat loss is critical for human survival in environmental factors and/or increased metabolism, heat a hot environment, particularly when environmental dissipation becomes vital for survival. In humans, the temperature is higher than skin temperature. Exercise or primary mechanism of heat dissipation, particularly when exposure to a hot environment elevates internal and skin ambient temperature is higher than skin temperature, is temperatures, and subsequently increases sweat rate and evaporative heat loss secondary to sweat secretion from skin blood flow. Historically it was thought that skin eccrine glands. While the primary controller of sweating is temperature was more important than internal temperature the integration between internal and skin temperatures, a in the control of sweating (24, 109). -

The Forearm Ischaemic Work Test - Hazardous to Mcardle Patients?

J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry: first published as 10.1136/jnnp.45.12.1144 on 1 December 1982. Downloaded from Journal ofNeurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry 1982;45:1144-1146 Short report The forearm ischaemic work test - hazardous to McArdle patients? HM MEINCK,* HH GOEBEL,t KW RUMPF,4 H KAISER,4 P NEUMANN§ From the Departments of Clinical Neurophysiology, * Neuropathology, t Medicinet and Nuclear Medicine,§ University of Gottingen, Gottingen, Federal Republic of Germany SUMMARY A 57-year-old patient suffering from late-onset McArdle's disease developed myoglobinaemia, massive myoglobinuria and marked serum creatine kinase elevation subsequent to a routinely performed forearm ischaemic work test. Twenty hours after the test, enhancement of99mTc methylene-diphosphonate activity was demonstrated exclusively in the tested forearm. It is concluded that the forearm ischaemic work test is potentially hazardous to McArdle patients, as it might induce myoglobinuria sufficient to result in acute myoglobinuric renal failure. The forearm ischaemic work test is established as a increased, and serum creatine kinase and creatinine levels guest. Protected by copyright. useful tool for differentiating between myopathies remained high. Serum lactate dehydrogenase (normally with and without defects of anaerobic glycogenolysis below 195 gi/l) was observed between values of 163 and 263 and glycolysis. So far no dangerous effects of this test I/l. Repeated ECGs and tests of left ventricular function have We report a case of late-onset (measured scintigraphically by means of gated blood pool been described. imaging) were normal. McArdle's disease' (glycogenosis V2), in which Neurological examination revealed atrophy and paresis massive myoglobinaemia and myoglobinuria (degrees III to IV on the MRC scale) of the shoulder girdle developed subsequent to this test. -

Development of a Functional in Vitro 3D Model of the Peripheral Nerve

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2018 Development of a Functional In Vitro 3D Model of the Peripheral Nerve Wesley Anderson University of Central Florida Part of the Disease Modeling Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Doctoral Dissertation (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Anderson, Wesley, "Development of a Functional In Vitro 3D Model of the Peripheral Nerve" (2018). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 5946. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/5946 DEVELOPMENT OF A FUNCTIONAL IN VITRO 3D MODEL OF THE PERIPHERAL NERVE by WESLEY ALLEN ANDERSON B.S. UNIVERSITY OF CENTRAL FLORIDA, 2011 M.S. UNIVERSITY OF CENTRAL FLORIDA, 2013 A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Burnett School of Biomedical Sciences in the College of Medicine at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Summer Term 2018 Major Professor: Stephen Lambert © 2018 Wesley Anderson ii ABSTRACT Peripheral neuropathies, affect approximately 20 million people in the United States and are often a complication of conditions such as diabetes that can result in amputation of affected areas such as the feet and toes. In vitro methodologies to facilitate the understanding and treatment of these disorders often lack the cellular and functional complexity required to accurately model peripheral neuropathies.