Reggae Ambassadors. La Légende Du Reggae

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Toots & the Maytals, Linton Kwesi Johnson

TOOTS & THE MAYTALS, LINTON KWESI JOHNSON: FULL CAMPAIGN DETAILS SEE PAGE IV 1 i ISUVHI If t Tr®(o®gs LKJ: biffs1 ^BOB MARLEY & THE WAITERS start their world tour with their first- A POET mmum 111111© ever Japanese concerts this month. The band also play in Australia - again a first - before hitting Hawaii in May. The Wailers' new album will be avail- &HIS able in June ... m ; -'.ii ^ A-.--: BIFFS THIRD WORLD are working on a new album, the follow-up to the brilliant JOURNEY TO ADDIS. The fm new elpee is being recorded in Los Angeles with Ibo, the band's key- boards player, as producer. Again, we're aiming for a summer release ... Tfi RIFFS O Toots Hibbert is a genuine reggae 1LPS 9534), which has been available t legend. Few artists can boast the kind since April 6. This is a stunning album, HI-TENSION'S new single will of revered status Toots has won for fully the equal of Toots' past achieve- be released in mid-May, just before himself over the past decade or so. ments, But, of course, you've already the band embark on a headlining Toots & The Maytals have been re- heard one of the tracks, FAMINE, British tour. Dates have yet to be sponsible for countless classics of which came out as a single back in finalised, but they will include at least Jamaican music during that period, January. FAMINE hit Radio One's one major London show^ from the compulsive DO THE REG- playlist and even figured in the BMRB/ GAY (the first time the word 'reggae', Music Week chart. -

Record Store Day 2020 (GSA) - 18.04.2020 | (Stand: 05.03.2020)

Record Store Day 2020 (GSA) - 18.04.2020 | (Stand: 05.03.2020) Vertrieb Interpret Titel Info Format Inhalt Label Genre Artikelnummer UPC/EAN AT+CH (ja/nein/über wen?) Exclusive Record Store Day version pressed on 7" picture disc! Top song on Billboard's 375Media Ace Of Base The Sign 7" 1 !K7 Pop SI 174427 730003726071 D 1994 Year End Chart. [ENG]Pink heavyweight 180 gram audiophile double vinyl LP. Not previously released on vinyl. 'Nam Myo Ho Ren Ge Kyo' was first released on CD only in 2007 by Ace Fu SPACE AGE 375MEDIA ACID MOTHERS TEMPLE NAM MYO HO REN GE KYO (RSD PINK VINYL) LP 2 PSYDEL 139791 5023693106519 AT: 375 / CH: Irascible Records and now re-mastered by John Rivers at Woodbine Street Studio especially for RECORDINGS vinyl Out of print on vinyl since 1984, FIRST official vinyl reissue since 1984 -Chet Baker (1929 - 1988) was an American jazz trumpeter, actor and vocalist that needs little introduction. This reissue was remastered by Peter Brussee (Herman Brood) and is featuring the original album cover shot by Hans Harzheim (Pharoah Sanders, Coltrane & TIDAL WAVES 375MEDIA BAKER, CHET MR. B LP 1 JAZZ 139267 0752505992549 AT: 375 / CH: Irascible Sun Ra). Also included are the original liner notes from jazz writer Wim Van Eyle and MUSIC two bonus tracks that were not on the original vinyl release. This reissue comes as a deluxe 180g vinyl edition with obi strip_released exclusively for Record Store Day (UK & Europe) 2020. * Record Store Day 2020 Exclusive Release.* Features new artwork* LP pressed on pink vinyl & housed in a gatefold jacket Limited to 500 copies//Last Tango in Paris" is a 1972 film directed by Bernardo Bertolucci, saxplayer Gato Barbieri' did realize the soundtrack. -

Congo Congo Mp3, Flac, Wma

Congo Congo mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Reggae Album: Congo Country: Canada Released: 1979 Style: Roots Reggae MP3 version RAR size: 1225 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1322 mb WMA version RAR size: 1867 mb Rating: 4.8 Votes: 711 Other Formats: AUD VOC MP4 MOD WAV VQF ASF Tracklist A1 Days Chasing Days 4:43 A2 Jackpot 5:10 A3 Hail The World Of Jah 4:24 A4 Education Of Brainwashing 3:20 B1 Youth Man 4:30 B2 Yoyo 4:43 B3 Nana 4:39 B4 Thief Is In The Vineyard 3:18 Companies, etc. Pressed By – CBS Disques Distributed By – CBS Disques Phonographic Copyright (p) – CBS Inc. Copyright (c) – CBS Inc. Printed By – Montreuil Offset Recorded At – Harry J's Recording Studio Recorded At – Aquarius Studio Mixed At – Dynamic Sounds Studios Credits Backing Vocals [Background Vocals] – Roy Johnson*, Watty Burnett Bass – Philippe Quilichini Drums – Santa*, Sly Dunbar (tracks: A3) Engineer [Ingénieurs Du Son] – Mervyn Williams, Sylvan Morris Lead Guitar – Ernest Ranglin (tracks: A3), Lennox Gordon Lead Vocals – Cedric Myton Mixed By [Mixé Par] – Geoffrey Chung, Nadette Duget Organ, Electric Piano, Piano [Acoustic Piano] – Harold Butler, Keith Sterling Percussion – Scully*, Congo*, Sticky* Producer [Produit Par] – Nadette Duget Rhythm Guitar – Earl "Chinna" Smith (tracks: A1, A3), Willie Lindo Saxophone – Tommy McCook Written-By – Cedric Myton, Roy Johnson* (tracks: A1, A3, A4, B1 to B4), Watty Burnett (tracks: A2, B2, B4) Notes Enregistré à Harry J. Studio, Aquarius Recording Co Ltd. Mixé à Dynamic Sounds Recordings Co Ltd. Kingston, Jamaïque, Février 79 [Mixed in February 1979]. Editeur: droits réservés Inner sleeve with photographs and lyrics. -

Read Or Download

afrique.q 7/15/02 12:36 PM Page 2 The tree of life that is reggae music in all its forms is deeply spreading its roots back into Afri- ca, idealized, championed and longed for in so many reggae anthems. African dancehall artists may very well represent the most exciting (and least- r e c o g n i z e d ) m o vement happening in dancehall today. Africa is so huge, culturally rich and diverse that it is difficult to generalize about the musical happenings. Yet a recent musical sampling of the continent shows that dancehall is begin- ning to emerge as a powerful African musical form in its own right. FromFrom thethe MotherlandMotherland....Danc....Danc By Lisa Poliak daara-j Coming primarily out of West Africa, artists such as Gambia’s Rebellion D’Recaller, Dancehall Masters and Senegal’s Daara-J, Pee GAMBIA Froiss and V.I.B. are creating their own sounds growing from a fertile musical and cultural Gambia is Africa’s cross-pollination that blends elements of hip- dancehall hot spot. hop, reggae and African rhythms such as Out of Gambia, Rebel- Senegalese mbalax, for instance. Most of lion D’Recaller and these artists have not yet spread their wings Dancehall Masters are on the international scene, especially in the creating music that is U.S., but all have the musical and lyrical skills less rap-influenced to explode globally. Chanting down Babylon, than what is coming these African artists are inspired by their out of Senegal. In Jamaican predecessors while making music Gambia, they’re basi- that is uniquely their own, praising Jah, Allah cally heavier on the and historical spiritual leaders. -

Jamaican Politics, Nationalism, and Musical Culture in Transition, 1974-1984

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations Dissertations and Theses 5-18-2007 Between Two Giant Sounds: Jamaican Politics, Nationalism, and Musical Culture in Transition, 1974-1984 Caree Banton University of New Orleans Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td Recommended Citation Banton, Caree, "Between Two Giant Sounds: Jamaican Politics, Nationalism, and Musical Culture in Transition, 1974-1984" (2007). University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations. 508. https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td/508 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by ScholarWorks@UNO with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Between Two Giant Sounds: Jamaican Politics, Nationalism, and Musical Culture in Transition, 1974 – 1984 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of New Orleans In partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Master of Arts In History By Caree Ann-Marie Banton B.A. Grambling State University 2005 B.P.A Grambling State University 2005 May 2007 Acknowledgement I would like to thank all the people that facilitated the completion of this work. -

Chant Down Babylon: the Rastafarian Movement and Its Theodicy for the Suffering

Verge 5 Blatter 1 Chant Down Babylon: the Rastafarian Movement and Its Theodicy for the Suffering Emily Blatter The Rastafarian movement was born out of the Jamaican ghettos, where the descendents of slaves have continued to suffer from concentrated poverty, high unemployment, violent crime, and scarce opportunities for upward mobility. From its conception, the Rastafarian faith has provided hope to the disenfranchised, strengthening displaced Africans with the promise that Jah Rastafari is watching over them and that they will someday find relief in the promised land of Africa. In The Sacred Canopy , Peter Berger offers a sociological perspective on religion. Berger defines theodicy as an explanation for evil through religious legitimations and a way to maintain society by providing explanations for prevailing social inequalities. Berger explains that there exist both theodicies of happiness and theodicies of suffering. Certainly, the Rastafarian faith has provided a theodicy of suffering, providing followers with religious meaning in social inequality. Yet the Rastafarian faith challenges Berger’s notion of theodicy. Berger argues that theodicy is a form of society maintenance because it allows people to justify the existence of social evils rather than working to end them. The Rastafarian theodicy of suffering is unique in that it defies mainstream society; indeed, sociologist Charles Reavis Price labels the movement antisystemic, meaning that it confronts certain aspects of mainstream society and that it poses an alternative vision for society (9). The Rastas believe that the white man has constructed and legitimated a society that is oppressive to the black man. They call this society Babylon, and Rastas make every attempt to defy Babylon by refusing to live by the oppressors’ rules; hence, they wear their hair in dreads, smoke marijuana, and adhere to Marcus Garvey’s Ethiopianism. -

Dancehall Dossier.Cdr

DANCEHALL DOSSIER STOP M URDER MUSIC DANCEHALL DOSSIER Beenie Man Beenie Man - Han Up Deh Hang chi chi gal wid a long piece of rope Hang lesbians with a long piece of rope Beenie Man Damn I'm dreaming of a new Jamaica, come to execute all the gays I'm dreaming of a new Jamaica, come to execute all the gays Beenie Man Beenie Man - Batty Man Fi Dead Real Name: Anthony M Davis (aka ‘Weh U No Fi Do’) Date of Birth: 22 August 1973 (Queers Must Be killed) All batty man fi dead! Jamaican dancehall-reggae star Beenie All faggots must be killed! Man has personally denied he had ever From you fuck batty den a coppa and lead apologised for his “kill gays” music and, to If you fuck arse, then you get copper and lead [bullets] prove it, performed songs inciting the murder of lesbian and gay people. Nuh man nuh fi have a another man in a him bed. No man must have another man in his bed In two separate articles, The Jamaica Observer newspaper revealed Beenie Man's disavowal of his apology at the Red Beenie Man - Roll Deep Stripe Summer Sizzle concert at James Roll deep motherfucka, kill pussy-sucker Bond Beach, Jamaica, on Sunday 22 August 2004. Roll deep motherfucker, kill pussy-sucker Pussy-sucker:a lesbian, or anyone who performs cunnilingus. “Beenie Man, who was celebrating his Tek a Bazooka and kill batty-fucker birthday, took time to point out that he did not apologise for his gay-bashing lyrics, Take a bazooka and kill bum-fuckers [gay men] and went on to perform some of his anti- gay tunes before delving into his popular hits,” wrote the Jamaica Observer QUICK FACTS “He delivered an explosive set during which he performed some of the singles that have drawn the ire of the international Virgin Records issued an apology on behalf Beenie Man but within gay community,” said the Observer. -

A Hard Days Night Angie About a Girl Acky Breaky Heart All Along the Watchtowers Angels All the Small Things Ain`T No Sunshine A

A hard days night Angie About a girl Acky breaky heart All along the watchtowers Angels All the small things Ain`t no sunshine All shook up Alberta Alive And I love her Anna (go to him) 500 miles 7 nation army Back to you Bad moon rising Be bop a lula Beds are burnng Big monkey man Bitter sweet symphony Big yellow taxi Blue suede shoes Born to be wild Breakfast at Tiffany`s Bonasera Brown eyed girl Can`t take my eyes off of you Californication Change the world Cigarettes and alcohol Cocain blues Baby,Come back Chasing cars Come together Creep Come as you are Cocain Cotton fields Crazy Country roads Crazy little thing called love Dont look back in anger Don't worry be happy Dancing in the moonlight Don`t stop belivin` Dance the night away Dead or alive Englishman in NY Every breath you take Easy Faith Feel like making love Fortunate son Fields of gold Further on up the road Free falling Gimme all your lovin' Gimme love Gimme all your love Great balls of fire Green grass of home Happy Hello Heart-shaped box Have you ever seen the rain Hello Mary Lou Highway to hell High and dry Hey jude Hotel california Human touch Hurt Hound dog (ISun Can't is shining Get No) Satisfaction I'm yours I don't wanna miss a thing I saw her staning there I got stripes I walk the line Imagine I`m a believer It`s my life (D) Impossible Jamming Johny be goode Keep on rockin` in a free world Knockin` on the heavens door Kingston town La bamba (E) Lay down Sally Learn to fly Light my fire Let her go Let it be Love is all around Layla Learning to fly Living next door -

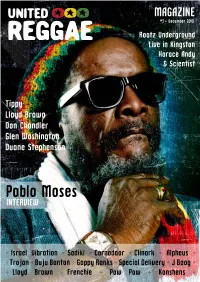

Pablo Moses INTERVIEW

MAGAZINE #3 - December 2010 Rootz Underground Live in Kingston Horace Andy & Scientist Tippy Lloyd Brown Don Chandler Glen Washington Duane Stephenson Pablo Moses INTERVIEW * Israel Vibration * Sadiki * Cornadoor * Clinark * Alpheus * * Trojan * Buju Banton * Gappy Ranks * Special Delivery * J Boog * * Lloyd Brown * Frenchie * Pow Pow * Konshens * United Reggae Mag #3 - December 2010 Want to read United Reggae as a paper magazine? In addition to the latest United Reggae news, views andNow videos you online can... each month you can now enjoy a free pdf version packed with most of United Reggae content from the last month.. SUMMARY 1/ NEWS •Lloyd Brown - Special Delivery - Own Mission Records - Calabash J Boog - Konshens - Trojan - Alpheus - Racer Riddim - Everlasting Riddim London International Ska Festival - Jamaican-roots.com - Buju Banton, Gappy Ranks, Irie Ites, Sadiki, Tiger Records 3 - 9 2/ INTERVIEWS •Interview: Tippy 11 •Interview: Pablo Moses 15 •Interview: Duane Stephenson 19 •Interview: Don Chandler 23 •Interview: Glen Washington 26 3/ REVIEWS •Voodoo Woman by Laurel Aitken 29 •Johnny Osbourne - Reggae Legend 30 •Cornerstone by Lloyd Brown 31 •Clinark - Tribute to Michael Jackson, A Legend and a Warrior •Without Restrictions by Cornadoor 32 •Keith Richards’ sublime Wingless Angels 33 •Reggae Knights by Israel Vibration 35 •Re-Birth by The Tamlins 36 •Jahdan Blakkamoore - Babylon Nightmare 37 4/ ARTICLES •Is reggae dying a slow death? 38 •Reggae Grammy is a Joke 39 •Meet Jah Turban 5/ PHOTOS •Summer Of Rootz 43 •Horace Andy and Scientist in Paris 49 •Red Strip Bold 2010 50 •Half Way Tree Live 52 All the articles in this magazine were previously published online on http://unitedreggae.com.This magazine is free for download at http://unitedreggae.com/magazine/. -

Carlton Barrett

! 2/,!.$ 4$ + 6 02/3%2)%3 f $25-+)4 7 6!,5%$!4 x]Ó -* Ê " /",½-Ê--1 t 4HE7ORLDS$RUM-AGAZINE !UGUST , -Ê Ê," -/ 9 ,""6 - "*Ê/ Ê /-]Ê /Ê/ Ê-"1 -] Ê , Ê "1/Ê/ Ê - "Ê Ê ,1 i>ÌÕÀ} " Ê, 9½-#!2,4/."!22%44 / Ê-// -½,,/9$+.)"" 7 Ê /-½'),3(!2/.% - " ½-Ê0(),,)0h&)3(v&)3(%2 "Ê "1 /½-!$2)!.9/5.' *ÕÃ -ODERN$RUMMERCOM -9Ê 1 , - /Ê 6- 9Ê `ÊÕV ÊÀit Volume 36, Number 8 • Cover photo by Adrian Boot © Fifty-Six Hope Road Music, Ltd CONTENTS 30 CARLTON BARRETT 54 WILLIE STEWART The songs of Bob Marley and the Wailers spoke a passionate mes- He spent decades turning global audiences on to the sage of political and social justice in a world of grinding inequality. magic of Third World’s reggae rhythms. These days his But it took a powerful engine to deliver the message, to help peo- focus is decidedly more grassroots. But his passion is as ple to believe and find hope. That engine was the beat of the infectious as ever. drummer known to his many admirers as “Field Marshal.” 56 STEVE NISBETT 36 JAMAICAN DRUMMING He barely knew what to do with a reggae groove when he THE EVOLUTION OF A STYLE started his climb to the top of the pops with Steel Pulse. He must have been a fast learner, though, because it wouldn’t Jamaican drumming expert and 2012 MD Pro Panelist Gil be long before the man known as Grizzly would become one Sharone schools us on the history and techniques of the of British reggae’s most identifiable figures. -

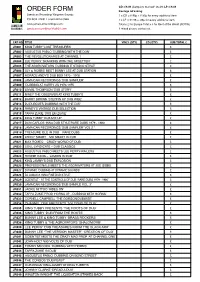

Order Form Order Form

CD: £9.49 (Samplers marked* £6.49) LP: £9.49 ORDER FORM Postage &Packing: Jamaican Recording/ Kingston Sounds 1 x CD = 0.95p + 0.35p for every additional item PO BOX 32691 London W14 OWH 1 x LP = £1.95 + .85p for every additional item JAMAICAN www.jamaicanrecordings.com Total x 2 for Europe Total x 3 for Rest of the World (ROTW) RECORDINGS [email protected] If mixed please contact us. CAT NO. TITLE VINLY (QTY) CD (QTY) SUB TOTAL £ JR001 KING TUBBY 'LOST TREASURES' £ JR002 AUGUSTUS PABLO 'DUBBING WITH THE DON' £ JR003 THE REVOLUTIONARIES AT CHANNEL 1 £ JR004 LEE PERRY 'SKANKING WITH THE UPSETTER' £ JR005 THE AGGROVATORS 'DUBBING IT STUDIO STYLE' £ JR006 SLY & ROBBIE MEET BUNNY LEE AT DUB STATION £ JR007 HORACE ANDY'S DUB BOX 1973 - 1976 £ JR008 JAMAICAN RECORDINGS 'DUB SAMPLER' £ JR009 'DUBBING AT HARRY J'S 1970-1975 £ JR010 LINVAL THOMPSON 'DUB STORY' £ JR011 NINEY THE OBSERVER AT KING TUBBY'S £ JR012 BARRY BROWN 'STEPPIN UP DUB WISE' £ JR013 DJ DUBCUTS 'DUBBING WITH THE DJS' £ JR014 RANDY’S VINTAGE DUB SELECTION £ JR015 TAPPA ZUKIE ‘DUB EM ZUKIE’ £ JR016 KING TUBBY ‘DUB MIX UP’ £ JR017 DON CARLOS ‘INNA DUB STYLE’RARE DUBS 1979 - 1980 £ JR018 JAMAICAN RECORDINGS 'DUB SAMPLER' VOL 2 * £ JR019 TREASURE ISLE IN DUB – RARE DUBS £ JR020 LEROY SMART – MR SMART IN DUB £ JR021 MAX ROMEO – CRAZY WORLD OF DUB £ JR022 SOUL SYNDICATE – DUB CLASSICS £ JR023 AUGUSTUS PABLO MEETS LEE PERRY/WAILERS £ JR024 RONNIE DAVIS – ‘JAMMIN IN DUB’ £ JR025 KING JAMMY’S DUB EXPLOSION £ JR026 PROFESSIONALS MEETS THE AGGRAVATORS AT JOE GIBBS £ JR027 DYNAMIC ‘DUBBING AT DYNAMIC SOUNDS’ £ JR028 DJ JAMAICA ‘INNA FINE DUB STYLE’ £ JR029 SCIENTIST - AT THE CONTROLS OF DUB ‘RARE DUBS 1979 - 1980’ £ JR030 JAMAICAN RECORDINGS ‘DUB SAMPLE VOL. -

Brand New Cd & Dvd Releases 2006 6,400 Titles

BRAND NEW CD & DVD RELEASES 2006 6,400 TITLES COB RECORDS, PORTHMADOG, GWYNEDD,WALES, U.K. LL49 9NA Tel. 01766 512170: Fax. 01766 513185: www. cobrecords.com // e-mail [email protected] CDs, DVDs Supplied World-Wide At Discount Prices – Exports Tax Free SYMBOLS USED - IMP = Imports. r/m = remastered. + = extra tracks. D/Dble = Double CD. *** = previously listed at a higher price, now reduced Please read this listing in conjunction with our “ CDs AT SPECIAL PRICES” feature as some of the more mainstream titles may be available at cheaper prices in that listing. Please note that all items listed on this 2006 6,400 titles listing are all of U.K. manufacture (apart from Imports which are denoted IM or IMP). Titles listed on our list of SPECIALS are a mix of U.K. and E.C. manufactured product. We will supply you with whichever item for the price/country of manufacture you choose to order. ************************************************************************************************************* (We Thank You For Using Stock Numbers Quoted On Left) 337 AFTER HOURS/G.DULLI ballads for little hyenas X5 11.60 239 ANATA conductor’s departure B5 12.00 327 AFTER THE FIRE a t f 2 B4 11.50 232 ANATHEMA a fine day to exit B4 11.50 ST Price Price 304 AG get dirty radio B5 12.00 272 ANDERSON, IAN collection Double X1 13.70 NO Code £. 215 AGAINST ALL AUTHOR restoration of chaos B5 12.00 347 ANDERSON, JON animatioin X2 12.80 92 ? & THE MYSTERIANS best of P8 8.30 305 AGALAH you already know B5 12.00 274 ANDERSON, JON tour of the universe DVD B7 13.00