Barbed Utopia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Unpacking “Gender Ideology” and the Global Right’S Antigender Countermovement

Elizabeth S. Corredor Unpacking “Gender Ideology” and the Global Right’s Antigender Countermovement n 2011, eighty French MPs of the Union for a Popular Movement employed I right-wing gender ideology rhetoric to oppose new biology textbooks that defined gender as socially constructed rather than biologically predeter- mined (Le Bars 2011; Fillod 2014; Brustier 2015).1 Opponents called gen- der theory a “totalitarian ideology, more oppressive and pernicious than the Marxist ideology” and asserted that it “risks destabilizing young people and adolescents and altering their development” (Le Bars 2011). Analogous language later reappeared in France between 2013 and 2014 in debates con- cerning same-sex marriage and reproductive assistance for LGBTQ1 cou- ples (Fillod 2014; Brustier 2015). While same-sex marriage was eventually approved, measures for alternative reproductive procedures and adoption for LGBTQ1 couples were denied. Additionally, a scholastic gender equal- ity program called the “ABCD of Equality,” which was intended to sup- port teachers in addressing gender stereotyping in schools, was canceled (Penketh 2014; Brustier 2015). The antigender mobilizations in France stimulated similar campaigns across Europe, all rooted in gender ideology rhetoric. In Italy, Croatia, Spain, Hungary, Poland, Ukraine, Germany, Aus- tria, and Slovakia, programs and legislation that sought to enhance gender and sexual equality have faced significant resistance and, in many cases, have been abandoned.2 Latin America appears to be the latest battleground as gender ideology backlash has entered political debates in Mexico, Brazil, Peru, Guatemala, I would like to thank Mona Lena Krook, Cynthia Daniels, Mary Hawkesworth, and The- rese A. Dolan for their careful readings of preliminary drafts of this article. -

PHIL 220 Introduction to Feminism Fall 1997

1 Introduction to Feminism PHIL 220 Spring 2012 University of Mary Washington Dr. Craig Vasey. Department of Classics, Philosophy, and Religion Trinkle 238. M,W 10-11; TR 3:30-5 pm Phone: 654-1342 [email protected] In teaching women, we have two choices: to lend our weight to the forces that indoctrinate women to passivity, self-depreciation and a sense of powerlessness, in which case the issue of "taking women students seriously" is a moot one; or to consider what we have to work against, as well as with, in ourselves, in our students, in the content of the curriculum, in the structure of the institution, in the society at large. And this means, first of all, taking ourselves seriously. Suppose we were to ask ourselves, simply: what does a woman need to know? Does she not, as a self-conscious, self-defining being, need a knowledge of her own history, her much politicized biology, an awareness of the creative work of women of the past, the skills and crafts and techniques and powers exercised by women in different times and cultures, a knowledge of women's rebellions and organized movements against our oppression and how they have been routed or diminished? Without such knowledge women live and have lived without context, vulnerable to the projections of male fantasy, male prescriptions for us, estranged from our own experience because our education has not reflected or echoed it. Adrienne Rich, "Taking Women Students Seriously" 1978 Rich's claims and questions, thirty-four years old now, seem to me to be just as valid today, and to deserve thoughtful consideration. -

Girls Made Of? the Discourse of Girl Power in Contemporary U.S

WHAT ARE LITTLE (EMPOWERED) GIRLS MADE OF? THE DISCOURSE OF GIRL POWER IN CONTEMPORARY U.S. POPULAR CULTURE Rosalind Sibielski A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY August 2010 Committee: Ellen Berry, Advisor Lesa Lockford, Graduate Faculty Representative Cynthia Baron Kimberly Coates © 2010 Rosalind Sibielski All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Ellen Berry, Advisor Beginning in the late 1990s, U.S. popular culture has been inundated with messages promoting “girl power.” This dissertation examines representations of girl power in the mass media, as well as popular literature and advertising images, in order to interrogate the ways in which the discourse of girl power has shaped cultural understandings of girlhood in the past twenty years. It also examines the ways in which that discourse has functioned as both an extension of and a response to social concerns about the safety, health and emotional well-being of girls in the United States at the turn of the millennium. Girl power popular culture texts are often discussed by commentators, fans and their creators as attempts to use media narratives and images to empower girls, either by providing them with models for how to enact empowered femininity or by providing them with positive representations that make them feel good about themselves as girls. However, this project is arguably limited by the focus in girl power texts on girls’ individual (as opposed to their structural) empowerment, as well as the failure of these texts to conceive of the exercise of power outside of patriarchal models. -

Gender Ideology” and the Global Right’S Antigender Countermovement

Elizabeth S. Corredor Unpacking “Gender Ideology” and the Global Right’s Antigender Countermovement n 2011, eighty French MPs of the Union for a Popular Movement employed I right-wing gender ideology rhetoric to oppose new biology textbooks that defined gender as socially constructed rather than biologically predeter- mined (Le Bars 2011; Fillod 2014; Brustier 2015).1 Opponents called gen- der theory a “totalitarian ideology, more oppressive and pernicious than the Marxist ideology” and asserted that it “risks destabilizing young people and adolescents and altering their development” (Le Bars 2011). Analogous language later reappeared in France between 2013 and 2014 in debates con- cerning same-sex marriage and reproductive assistance for LGBTQ1 cou- ples (Fillod 2014; Brustier 2015). While same-sex marriage was eventually approved, measures for alternative reproductive procedures and adoption for LGBTQ1 couples were denied. Additionally, a scholastic gender equal- ity program called the “ABCD of Equality,” which was intended to sup- port teachers in addressing gender stereotyping in schools, was canceled (Penketh 2014; Brustier 2015). The antigender mobilizations in France stimulated similar campaigns across Europe, all rooted in gender ideology rhetoric. In Italy, Croatia, Spain, Hungary, Poland, Ukraine, Germany, Aus- tria, and Slovakia, programs and legislation that sought to enhance gender and sexual equality have faced significant resistance and, in many cases, have been abandoned.2 Latin America appears to be the latest battleground as gender ideology backlash has entered political debates in Mexico, Brazil, Peru, Guatemala, I would like to thank Mona Lena Krook, Cynthia Daniels, Mary Hawkesworth, and The- rese A. Dolan for their careful readings of preliminary drafts of this article. -

GENDER TROUBLE: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity

GENDER TROUBLE GENDER TROUBLE Feminism and the Subversion of Identity JUDITH BUTLER Routledge New York and London Published in 1999 by Routledge 29 West 35th Street New York, NY 10001 Published in Great Britain by Routledge 11 New Fetter Lane London EC4P 4EE This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2002. Copyright © 1990, 1999 by Routledge Gender Trouble was originally published in the Routledge book series Thinking Gender, edited by Linda J. Nicholson. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Butler, Judith P. Gender trouble : feminism and the subversion of identity / Judith Butler. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. Originally published: New York : Routledge, 1990. ISBN 0-415-92499-5 (pbk.) 1. Feminist theory. 2. Sex role. 3. Sex differences (Psychology) 4. Identity (Psychology) 5. Femininity. I.Title. HQ1154.B898 1999 305.3—dc21 99-29349 CIP ISBN 0-203-90275-0 Master e-book ISBN ISBN 0-203-90279-3 (Glassbook Format) Contents Preface () vii Preface () xxvii One Subjects of Sex/Gender/Desire 3 i “Women” as the Subject of Feminism 3 ii The Compulsory Order of Sex/ Gender/Desire 9 iii Gender:The Circular Ruins of Contemporary Debate 11 iv Theorizing the Binary, the Unitary, and -

The Impossible Country Rear Guard Scientists

The THE NEWSPAPER OF THE LITERARY ARTS Volume 4, N umber 5 September 1994 Ithaca, New York The Impossible Country Nicolas Vaczek In spring and summer of 1991, Ithaca’s Brian Hall traveled through the former Yugoslavia, witnessing the onset of civil war. One of the last foreigners to have traveled there unhindered, Hall in his new book, The Impossible Country (David R. Godine), has captured the voices o f the prominent and the unknown, from Slo bodan Milosevic to a wide variety of “real, likeable people” throughout Bosnia, Serbia, and Croatia. In addition, the book provides indispensable historical background, showing how Yugoslavia was formed after World War I, and explaining why every attempt at polit ical compromise has been met with suspicion and resis tance. Nicolas Vaczek recently interviewed Brian Hall in Ithaca. NV: Anyone writing in the travel mode on Yugoslavia has Rebecca West’s Black Lamb and Grey Falcon to contend with. BH: Yes. It’s a fabulous book. One of the greatest travel books ever written. She was there in 1937, though it’s not clear how much time she spent. If you read between the lines it doesn’t seem long. World War II is on the way. She’s writing from 1939 to 1940, and then she could retroactively put in some of her awareness. By 1940, she’s getting bombed in London by the Germans. By that time, Yugoslavia has become for her the symbol of a certain kind of decent civilization, represented by the Serbs under siege by the barbaric Germans. By the time I started writing my book, the war had begun in Bosnia. -

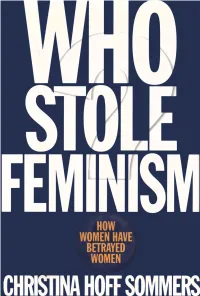

Who Stole Feminism? Is a Call to Arms That Will Enrage Or Inspire, but Cannot Be Ignored

FEMINISM HOW WOMEN HAVE BETRAYED WOMEN CHRISTINA HOFF SUMMERS U.S. $23.00 Can. $29.50 Philosophy professor Christina Sommers has exposed a disturbing development: how a group of zealots, claiming to speak for all women, are promoting a dangerous new agenda that threatens our most cherished ide als and sets women against men in all spheres of life. In case after case, Sommers shows how these extrem ists have propped up their arguments with highly questionable but well-fund ed research, presenting inflamma tory and often inaccurate information and stifling any sem blance of free and open scrutiny. Trumpeted as orthodoxy, the resulting "findings" on everything from rape to domestic abuse to economic bias to the supposed crisis in girls' self- esteem perpetuate a view of women as victims of the "patriarchy." Moreover, these arguments and the supposed facts on which they are based have had enormous influence beyond the academy, where they have shaken the foundations of our educa tional, scientific, and legal institutions and have fostered resentment and alienation in our private lives. Despite its current dominance, Sommers maintains, such a breed of feminism is at odds with the real aspirations and values of most American women and undermines the cause of true equality. Who Stole Feminism? is a call to arms that will enrage or inspire, but cannot be ignored. CHRISTINA HOFF SOMMERS is an associ ate professor of philosophy at Clark University who specializes in contem porary moral theory. The editor of two ethics textbooks, she has published numerous professional papers. She has also written articles for The New Republic, The Wall Street Journal, the Chicago Tribune, and The New England Journal of Medicine, among other publications. -

Open Omara Dissfinaldraft.Pdf

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School College of the Liberal Arts FEMINIST REFLECTIONS ON THE NATURE/CULTURE DISTINCTION IN MERLEAU-PONTYAN PHILOSOPHY A Dissertation in Philosophy by Cameron Matthew O’Mara 2013 Cameron Matthew O’Mara Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2013 The dissertation of Cameron Matthew O’Mara was reviewed and approved* by the following: Dr. Leonard Lawlor Edwin Erle Sparks Professor of Philosophy Dissertation Advisor Chair of Committee Dr. Robert Bernasconi Edwin Erle Sparks Professor of Philosophy Dr. Claire Colebrook Edwin Erle Sparks Professor of English Dr. Véronique Fóti Professor of Philosophy Dr. Shannon Sullivan Professor of Philosophy, Women’s Studies, and African and African American Studies Philosophy Department Head *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School iii ABSTRACT The purpose of this project is twofold: first, I trace the concepts of “nature” and “culture” throughout Merleau-Ponty’s corpus, drawing from select texts that highlight significant moments in the development of his thought. I show how nature and culture function as a problematic dualism that Merleau-Ponty is unable to collapse until his third course on Nature given at the Collège de France. I demonstrate that throughout Merleau-Ponty’s works, the human-animal relation serves to both trouble, yet reiterate this distinction. It is only when Merleau-Ponty begins to understand culture as institution, and to theorize the expressivity inherent in nature via institution, that he finds the means of positing the animal and the human, and later, the natural and the cultural, within a new model of difference that does not suggest an ontological divide between them. -

APA Newsletters

APA Newsletters Volume 01, Number 2 Spring 2002 NEWSLETTER ON FEMINISM AND PHILOSOPHY FROM THE EDITOR, JOAN CALLAHAN NEWS FROM THE COMMITTEE ON THE STATUS OF WOMEN, NANCY TUANA APA COMMITTEE ON THE STATUS OF WOMEN, 2001-2002 ARTICLES: FEMINIST VIRTUE THEORY AND ETHICS, Andrea Nicki, Guest Editor ANDREA NICKI “Introduction: Feminist Virtue Theory and Ethics” LISA TESSMAN “Do the Wicked Flourish? Virtue Ethics and Unjust Social Privilege” JOAN WOOLFREY “Feminist Awareness as Virtue: A Path of Moderation” WENDY DONNER “Feminist Ethics and Anger: A Feminist Buddhist Reflection” ANDREA NICKI “Envy, Self-Protection, and Moral Protection” SANDRA LEE BARTKY “Semper Fidelis? Some Observations on Adultery” BOOK REVIEW Christine Pierce: Immovable Laws Irresistible Rights: Natural Laws, Moral Rights, and Feminist Ethics REVIEWED BY VICTORIA DAVION ANNOUNCEMENTS NOTES ON CONTRIBUTORS © 2002 by The American Philosophical Association ISSN: 1067-9464 APA NEWSLETTER ON Feminism and Philosophy Andrea Nicki, Guest Editor Spring 2002 Volume 01, Number 2 always in need of book reviewers. To volunteer to review books (or some particular book), please send a CV and letter FROM THE EDITOR of interest, including mention of your areas of research and teaching. 3. Where to Send Things: Please send all articles, comments, Joan Callahan suggestions, books, and other communications to the Editor: Professor Joan Callahan, c/o Women’s Studies, 112 Current Issue: “Feminist Virtue Theory and Ethics,” Andrea Breckinridge Hall, University of Kentucky, Lexington, KY 40506- Nicki, Guest Editor 0056. If you want to send materials by email, this is fine, but Future Thematic Issues: “Diversity and Its Discontents,” Fall please be sure that they are in Microsoft Word. -

Women's Voice

Illinois State University Women’s Studies Program Volume 11, Issue 1, Sept/Oct 2005 Women’s Studies Launches We offer a minor and graduate certificate. We support student Five-Year Planning Process activism on campus. Our courses and programming are more multicultural than most others on campus. We run a successful By Alison Bailey annual student research symposium. We administer the Luellen Laurenti and Dorothy E. Lee scholarships. We are Thirty-five women’s studies affiliated faculty, students, and expanding our affiliated faculty base and graduate program. community members met on September 15 to discuss the future of the Women’s Studies Program at Illinois State We are fabulous, but we could be more fabulous. We need a University. The retreat was the first phase in a four-phased makeover of spa-sized proportions. As a small underfunded process designed to move the program forward in line with the program, most of our resources are regularly channeled into College of Arts and Sciences Five-Year Strategic Plan. It was staffing our feeder course (WS 120) and into extracurricular probably the first time that so many people affiliated with the programming. Like most women, the Women’s Studies program gathered together to talk candidly about the program. Program has taken the time to care for others, and needs to do Participants expressed their delight in seeing so many feminist more to care for itself. faculty together, and in being introduced to many people they had not met. Those who were unable to attend contributed by Retreat participants suggested that we begin to think about completing a questionnaire and attending one of three lunch- organizing opportunities for collaborative research among time focus groups. -

Democratic Culture. Newsletter of Teachers for a Democratic Culture

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 377 780 HE 027 964 AUTHOR Wilson, John K., Ed. TITLE Democratic Culture. Newsletter of Teachers for a Democratic Culture. Volumes 1-3. INSTITUTION Teachers for a Democratic Culture, Evanston, IL. PUB DATE 94 NOTE 121p, AVAILABLE FROM Teachers for a Democratic Culture, P.O. Box 6405, Evanston, IL 60204 ($5, single copy price; annual membership: $5, students/low-income; $25, faculty/others). PUB TYPE Collected Works Serials (022) JOURNAL CIT Democratic Culture; v1-3 Fall 1992-Fall 1994 EDRS PRICE MF01/PC05 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Academic Freedom; College Faculty; Culture; Culture Conflict; *Democracy; Democratic Values; Faculty College Relationship; Feminism; Government School Relationship; *Higher Education; *Politics of Education; Scholarship; School Community Relationship IDENTIFIERS Academic Community; Academic Discourse; Political Analysis; *Political Correctness; Political Criticism; Political Culture; Political Education ABSTRACT This document contains the first five issues of a newsletter for college faculty on countering the publicity campaign against "political correctness." The first issue from Fall 1992 describes the organization's founding and first year, analyzes a lawsuit brought by a faculty member at Massachusetts Institute of Technology against her institution charging acquiescing in "a persistent and continuing pattern of professional, political and sexual harassment," reviews books of interest, and reports on media coverage of "political correctness." The Spring 1993 issue includes reports on a -

Feminism, Capitalism, and Critique, DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-52386-6 282 NANCY FRASER’S BIBLIOGRAPHY

NANCY FRASER’S BIBLIOGRAPHY I. BOOKS Nancy Fraser, Unruly Practices: Power, Discourse and Gender in Contemporary Social Theory (University of Minnesota Press and Polity Press, 1989). German translation: Widerspenstige Praktiken: Macht, Diskurs, Geschlecht, trans. Karin Wördemann (Frankfurt: Suhrkamp Verlag 1994). Seyla Benhabib, Judith Butler, Drucilla Cornell and Nancy Fraser, Feminist Contentions: A Philosophical Exchange (Routledge, 1994). German translation: Der Streit um Differenz (Frankfurt: Fischer Verlag, 1993). Turkish translation: (Istanbul: Metis, 2008). Czech translation: (Prague: SLON Publishers). Nancy Fraser, Justice Interruptus: Critical Reflections on the “Postsocialist” Condition (Routledge, 1997). German translation: Die halbierte Gerechtigkeit, trans. Karin Wördemann (Frankfurt: Suhrkamp Verlag, 2001). Spanish translation: Iustitia Interrupta: Reflexiones críticas desde la posición “post- socialista,” trans. Maria Gomez (Bogota: Siglo del Hombres Editores, 1997). Japanese translation: trans. Masaki Nakamasa (Tokyo: Ochanomizushobo Publishers, 2003). Chinese translation: trans. Yu Haiqing (Shanghai: People’s Publishing Company, 2009). Italian translation: trans. Irene Strazzeri (Lecce: Pensa MultiMedia, 2009). Nancy Fraser and Axel Honneth, Redistribution or Recognition? A Political- Philosophical Exchange, trans. Joel Golb, James Ingram, and Christiane Wilke (London: Verso, 2003). © The Author(s) 2017 281 B. Bargu, C. Bottici (eds.), Feminism, Capitalism, and Critique, DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-52386-6 282 NANCY FRASER’S