From Structure to Function

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Arginine Kinase: a Crystallographic Investigation of Essential Substrate Structure Shawn A

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2006 Arginine Kinase: A Crystallographic Investigation of Essential Substrate Structure Shawn A. (Shawn Adam) Clark Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES ARGININE KINASE; A CRYSTALLOGRAPHIC INVESTIGATION OF ESSENTIAL SUBSTRATE STRUCTURE BY SHAWN A. CLARK A Dissertation submitted to the Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Fall Semester, 2006 The members of committee approve the dissertation of Shawn A. Clark defended on 11/2/2006 __________________ Michael Chapman Professor Co-Directing Dissertation __________________ Tim Logan Professor Co-Directing Dissertation __________________ Ross Ellington Outside Committee Member __________________ Al Stiegman Committee Member _________________ Tim Cross Committee Member Approved: ________________________________________ Naresh Dalal, Department Chair, Department of Chemistry & Biochemistry The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The voyage through academic maturity is full of numerous challenges that present themselves at many levels: physically, mentally, and emotionally. These hurdles can only be overcome with dedication, guidance, patience and above all support. It is for these reasons that I would like to express my sincerest and deepest admiration and love for my family; my wife Bobbi, and my two children Allexis and Brytney. Their encouragement, sacrifice, patience, loving support, and inquisitive nature have been the pillar of my strength, the beacon of my determination, and the spark of my intuition. -

Yeast Genome Gazetteer P35-65

gazetteer Metabolism 35 tRNA modification mitochondrial transport amino-acid metabolism other tRNA-transcription activities vesicular transport (Golgi network, etc.) nitrogen and sulphur metabolism mRNA synthesis peroxisomal transport nucleotide metabolism mRNA processing (splicing) vacuolar transport phosphate metabolism mRNA processing (5’-end, 3’-end processing extracellular transport carbohydrate metabolism and mRNA degradation) cellular import lipid, fatty-acid and sterol metabolism other mRNA-transcription activities other intracellular-transport activities biosynthesis of vitamins, cofactors and RNA transport prosthetic groups other transcription activities Cellular organization and biogenesis 54 ionic homeostasis organization and biogenesis of cell wall and Protein synthesis 48 plasma membrane Energy 40 ribosomal proteins organization and biogenesis of glycolysis translation (initiation,elongation and cytoskeleton gluconeogenesis termination) organization and biogenesis of endoplasmic pentose-phosphate pathway translational control reticulum and Golgi tricarboxylic-acid pathway tRNA synthetases organization and biogenesis of chromosome respiration other protein-synthesis activities structure fermentation mitochondrial organization and biogenesis metabolism of energy reserves (glycogen Protein destination 49 peroxisomal organization and biogenesis and trehalose) protein folding and stabilization endosomal organization and biogenesis other energy-generation activities protein targeting, sorting and translocation vacuolar and lysosomal -

(12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 6,387,890 B1 Christianson Et Al

USOO638789OB1 (12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 6,387,890 B1 Christianson et al. (45) Date of Patent: May 14, 2002 (54) COMPOSITIONS AND METHODS FOR CA:87:6321 abs of Diss Abstr Int B 37(8) pp. 3927-8 by INHIBITING ARGINASE ACTIVITY Hartz. Albina et al., 1995, J. Immunol. 155:4391-4396. (75) Inventors: David Christianson, Media, PA (US); Bacon et al., 1988, J. Mol. Graph. 6:219–200. Ricky Baggio, Waltham; Daniel Baker et al., 1980, Fed. Proc., Fed. Am. Soc. Exp. Biol. Elbaum, Newton, both of MA (US) 39:1686. Baker et al., 1983, Biochemistry 22:2098-2103. (73) Assignee: Trustees of the University of Bergeron et al., 1987, J. Org. Chem. 52:1700–1703. Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA (US) Biancani et al., 1985, Gastroenterology 89:867-874. - 0 Boden, 1975, Synthesis 784. (*) Notice: Subject to any disclaimer, the term of this Boucher et al., 1994, Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. patent is extended or adjusted under 35 2O3:1614-1621. U.S.C. 154(b) by 0 days. Bringer et al., 1987, Science 235:458–460. Bringer et al., 1998, Acta Crystallogr. D54:905-921. (21) Appl. No.: 09/545,737 Campos et al., 1995, J. Biol. Chem. 270:1721–1728. Cavaili et al., 1994, Biochemistry 33:10652–10657. (22) Filed: Apr. 10, 2000 Chakder and Rattan, 1997, J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 282:378-384. Related U.S. Application Data Chakder and Rattan, 1993, Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. (63) Continuation-in-part of application No. PCT/US98/21430, Liver Physiol. 264:G7-G12. filed on Oct. -

Exploring the Chemistry and Evolution of the Isomerases

Exploring the chemistry and evolution of the isomerases Sergio Martínez Cuestaa, Syed Asad Rahmana, and Janet M. Thorntona,1 aEuropean Molecular Biology Laboratory, European Bioinformatics Institute, Wellcome Trust Genome Campus, Hinxton, Cambridge CB10 1SD, United Kingdom Edited by Gregory A. Petsko, Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, NY, and approved January 12, 2016 (received for review May 14, 2015) Isomerization reactions are fundamental in biology, and isomers identifier serves as a bridge between biochemical data and ge- usually differ in their biological role and pharmacological effects. nomic sequences allowing the assignment of enzymatic activity to In this study, we have cataloged the isomerization reactions known genes and proteins in the functional annotation of genomes. to occur in biology using a combination of manual and computa- Isomerases represent one of the six EC classes and are subdivided tional approaches. This method provides a robust basis for compar- into six subclasses, 17 sub-subclasses, and 245 EC numbers cor- A ison and clustering of the reactions into classes. Comparing our responding to around 300 biochemical reactions (Fig. 1 ). results with the Enzyme Commission (EC) classification, the standard Although the catalytic mechanisms of isomerases have already approach to represent enzyme function on the basis of the overall been partially investigated (3, 12, 13), with the flood of new data, an integrated overview of the chemistry of isomerization in bi- chemistry of the catalyzed reaction, expands our understanding of ology is timely. This study combines manual examination of the the biochemistry of isomerization. The grouping of reactions in- chemistry and structures of isomerases with recent developments volving stereoisomerism is straightforward with two distinct types cis-trans in the automatic search and comparison of reactions. -

(10) Patent No.: US 8119385 B2

US008119385B2 (12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 8,119,385 B2 Mathur et al. (45) Date of Patent: Feb. 21, 2012 (54) NUCLEICACIDS AND PROTEINS AND (52) U.S. Cl. ........................................ 435/212:530/350 METHODS FOR MAKING AND USING THEMI (58) Field of Classification Search ........................ None (75) Inventors: Eric J. Mathur, San Diego, CA (US); See application file for complete search history. Cathy Chang, San Diego, CA (US) (56) References Cited (73) Assignee: BP Corporation North America Inc., Houston, TX (US) OTHER PUBLICATIONS c Mount, Bioinformatics, Cold Spring Harbor Press, Cold Spring Har (*) Notice: Subject to any disclaimer, the term of this bor New York, 2001, pp. 382-393.* patent is extended or adjusted under 35 Spencer et al., “Whole-Genome Sequence Variation among Multiple U.S.C. 154(b) by 689 days. Isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa” J. Bacteriol. (2003) 185: 1316 1325. (21) Appl. No.: 11/817,403 Database Sequence GenBank Accession No. BZ569932 Dec. 17. 1-1. 2002. (22) PCT Fled: Mar. 3, 2006 Omiecinski et al., “Epoxide Hydrolase-Polymorphism and role in (86). PCT No.: PCT/US2OO6/OOT642 toxicology” Toxicol. Lett. (2000) 1.12: 365-370. S371 (c)(1), * cited by examiner (2), (4) Date: May 7, 2008 Primary Examiner — James Martinell (87) PCT Pub. No.: WO2006/096527 (74) Attorney, Agent, or Firm — Kalim S. Fuzail PCT Pub. Date: Sep. 14, 2006 (57) ABSTRACT (65) Prior Publication Data The invention provides polypeptides, including enzymes, structural proteins and binding proteins, polynucleotides US 201O/OO11456A1 Jan. 14, 2010 encoding these polypeptides, and methods of making and using these polynucleotides and polypeptides. -

Amino Acid Residue. Chorismate Mutase by Variation of a Single

Modulation of the allosteric equilibrium of yeast chorismate mutase by variation of a single amino acid residue. R Graf, Y Dubaquié and G H Braus J. Bacteriol. 1995, 177(6):1645. Downloaded from Updated information and services can be found at: http://jb.asm.org/content/177/6/1645 These include: CONTENT ALERTS Receive: RSS Feeds, eTOCs, free email alerts (when new articles cite this article), more» http://jb.asm.org/ on March 22, 2013 by guest Information about commercial reprint orders: http://journals.asm.org/site/misc/reprints.xhtml To subscribe to to another ASM Journal go to: http://journals.asm.org/site/subscriptions/ JOURNAL OF BACTERIOLOGY, Mar. 1995, p. 1645–1648 Vol. 177, No. 6 0021-9193/95/$04.0010 Copyright q 1995, American Society for Microbiology Modulation of the Allosteric Equilibrium of Yeast Chorismate Mutase by Variation of a Single Amino Acid Residue RONEY GRAF,† YVES DUBAQUIE´,‡ AND GERHARD H. BRAUS* Institut fu¨r Mikrobiologie, Biochemie & Genetik, Friedrich-Alexander Universita¨t Erlangen-Nu¨rnberg, D-91058 Erlangen, Germany Received 26 September 1994/Accepted 11 January 1995 Chorismate mutase (EC 5.4.99.5) from the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae is an allosteric enzyme which can be locked in its active R (relaxed) state by a single threonine-to-isoleucine exchange at position 226. Seven new replacements of residue 226 reveal that this position is able to direct the enzyme’s allosteric equilibrium, without interfering with the catalytic constant or the affinity for the activator. Downloaded from Chorismate is the last common precursor of the amino acids amino acid 226 of yeast chorismate mutase to glycine and tyrosine, phenylalanine, and tryptophan and an important in- alanine (small), aspartate and arginine (charged), serine (hy- termediate in the biosynthesis of other aromatic compounds in drophilic, similar to the wild-type threonine), cysteine (sulfur fungi, bacteria, and plants (9). -

24666Hakda.Pdf

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies Legacy Theses 1997 The properties of beta-galactosidases from Escherichia coli with substitutions for glycine 794 and tryptophan 999 Hakda, Shamina Hakda, S. (1997). The properties of beta-galactosidases from Escherichia coli with substitutions for glycine 794 and tryptophan 999 (Unpublished master's thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. doi:10.11575/PRISM/13125 http://hdl.handle.net/1880/26631 master thesis University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca THE UNZVERSITY OF CALGARY The hperties of 8-Galactosidases hmEscherichia coli With Substitutions for Glycine 794 and Tryptophan 999 Shamina Hakda A THESIS SUBMlTTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE DEPARTMENT OF BIOLOGICAL SCIENCES CALGARY,ALBERTA AUGUST, 1997 O Shamina Hakda 1997 National Library Bibliothèque nationale of Canada du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographie Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Ottawa ON KiA ON4 Canada Canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National Library of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distrhute or seil reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microfonn, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. -

Thermodynamic and Extrathermodynamic Requirements of Enzyme Catalysis

Biophysical Chemistry 105 (2003) 559–572 Thermodynamic and extrathermodynamic requirements of enzyme catalysis Richard Wolfenden* Department of Biochemistry and Biophysics, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC 27599-7260, USA Received 24 October 2002; received in revised form 22 January 2003; accepted 22 January 2003 Abstract An enzyme’s affinity for the altered substrate in the transition state (symbolized here as S‡) matches the value of kcatyK m divided by the rate constant for the uncatalyzed reaction in water. The validity of this relationship is not affected by the detailed mechanism by which any particular enzyme may act, or on whether changes in enzyme conformation occur on the path to the transition state. It subsumes potential effects of substrate desolvation, H- bonding and other polar attractions, and the juxtaposition of several substrates in a configuration appropriate for reaction. The startling rate enhancements that some enzymes produce have only recently been recognized. Direct measurements of the binding affinities of stable transition-state analog inhibitors confirm the remarkable power of binding discrimination of enzymes. Several parts of the enzyme and substrate, that contribute to S‡ binding, exhibit extremely large connectivity effects, with effective relative concentrations in excess of 108 M. Exact structures of enzyme complexes with transition-state analogs also indicate a general tendency of enzyme active sites to close around S‡ in such a way as to maximize binding contacts. The role of solvent water in these binding equilibria, for which Walter Kauzmann provided a primer, is only beginning to be appreciated. ᮊ 2003 Elsevier Science B.V. All rights reserved. -

O O2 Enzymes Available from Sigma Enzymes Available from Sigma

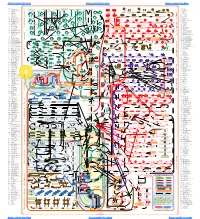

COO 2.7.1.15 Ribokinase OXIDOREDUCTASES CONH2 COO 2.7.1.16 Ribulokinase 1.1.1.1 Alcohol dehydrogenase BLOOD GROUP + O O + O O 1.1.1.3 Homoserine dehydrogenase HYALURONIC ACID DERMATAN ALGINATES O-ANTIGENS STARCH GLYCOGEN CH COO N COO 2.7.1.17 Xylulokinase P GLYCOPROTEINS SUBSTANCES 2 OH N + COO 1.1.1.8 Glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase Ribose -O - P - O - P - O- Adenosine(P) Ribose - O - P - O - P - O -Adenosine NICOTINATE 2.7.1.19 Phosphoribulokinase GANGLIOSIDES PEPTIDO- CH OH CH OH N 1 + COO 1.1.1.9 D-Xylulose reductase 2 2 NH .2.1 2.7.1.24 Dephospho-CoA kinase O CHITIN CHONDROITIN PECTIN INULIN CELLULOSE O O NH O O O O Ribose- P 2.4 N N RP 1.1.1.10 l-Xylulose reductase MUCINS GLYCAN 6.3.5.1 2.7.7.18 2.7.1.25 Adenylylsulfate kinase CH2OH HO Indoleacetate Indoxyl + 1.1.1.14 l-Iditol dehydrogenase L O O O Desamino-NAD Nicotinate- Quinolinate- A 2.7.1.28 Triokinase O O 1.1.1.132 HO (Auxin) NAD(P) 6.3.1.5 2.4.2.19 1.1.1.19 Glucuronate reductase CHOH - 2.4.1.68 CH3 OH OH OH nucleotide 2.7.1.30 Glycerol kinase Y - COO nucleotide 2.7.1.31 Glycerate kinase 1.1.1.21 Aldehyde reductase AcNH CHOH COO 6.3.2.7-10 2.4.1.69 O 1.2.3.7 2.4.2.19 R OPPT OH OH + 1.1.1.22 UDPglucose dehydrogenase 2.4.99.7 HO O OPPU HO 2.7.1.32 Choline kinase S CH2OH 6.3.2.13 OH OPPU CH HO CH2CH(NH3)COO HO CH CH NH HO CH2CH2NHCOCH3 CH O CH CH NHCOCH COO 1.1.1.23 Histidinol dehydrogenase OPC 2.4.1.17 3 2.4.1.29 CH CHO 2 2 2 3 2 2 3 O 2.7.1.33 Pantothenate kinase CH3CH NHAC OH OH OH LACTOSE 2 COO 1.1.1.25 Shikimate dehydrogenase A HO HO OPPG CH OH 2.7.1.34 Pantetheine kinase UDP- TDP-Rhamnose 2 NH NH NH NH N M 2.7.1.36 Mevalonate kinase 1.1.1.27 Lactate dehydrogenase HO COO- GDP- 2.4.1.21 O NH NH 4.1.1.28 2.3.1.5 2.1.1.4 1.1.1.29 Glycerate dehydrogenase C UDP-N-Ac-Muramate Iduronate OH 2.4.1.1 2.4.1.11 HO 5-Hydroxy- 5-Hydroxytryptamine N-Acetyl-serotonin N-Acetyl-5-O-methyl-serotonin Quinolinate 2.7.1.39 Homoserine kinase Mannuronate CH3 etc. -

Syntheses of Chorismate Analogs for Investigation of Structural Requirements for Chorismate Mutase

Syntheses of Chorismate Analogs for Investigation of Structural Requirements for Chorismate Mutase by Chang-Chung Cheng B.S., Department of Chemistry National Chung-Hsing University 1986 Submitted to the Department of Chemistry in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Organic Chemistry at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology May, 1994 © 1994 Chang-Chung Cheng All rights reserved The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in oart. Signature of Author... ............ ............ ......................................................... Department of Chemistry May 18, 1994 Certified by...................................... Glenn A. Berchtold Thesis Supervisor Accepted by..........................................-. ,..... ......................................................... Glenn A. Berchtold Science Chairman, Departmental Committee on Graduate Studies JUN 2 1 1994 LjENrVUVk*_ This doctoral thesis has been examined by a Committee of the Department of Chemistry as Follows: Professor Frederick D. Greene, II......... .......... Chairman Professor Glenn A. Berchtold .ThS................................ Thesis Supervisor Professor Julius Rebek, Jr............... .. ............................................L% 1 Foreword Chang-Chung (Cliff) Cheng's Ph. D. thesis is a special thesis for me because of our association with the individual who supervised his undergraduate research and since Cliff will be the last student to receive the Ph. D. from me during my career at M.I.T.. Cliff received the B.S. degree in Chemistry from National Chung-Hsing University, Taichung, Taiwan in June 1986, and he enrolled in our doctoral program in September 1989. During his undergraduate career Cliff was engaged in research under the supervision of Professor Teng-Kuei Yang. Professor Yang also received his undergraduate training in chemistry at National Chung-Hsing University before coming to the United States to complete the Ph. -

Building Microbial Factories for The

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Metabolic Engineering journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/meteng Building microbial factories for the production of aromatic amino acid pathway derivatives: From commodity chemicals to plant-sourced natural products ∗ Mingfeng Caoa,b,1, Meirong Gaoa,b,1, Miguel Suásteguia,b, Yanzhen Meie, Zengyi Shaoa,b,c,d, a Department of Chemical and Biological Engineering, Iowa State University, USA b NSF Engineering Research Center for Biorenewable Chemicals (CBiRC), Iowa State University, USA c Interdepartmental Microbiology Program, Iowa State University, USA d The Ames Laboratory, USA e School of Life Sciences, No.1 Wenyuan Road, Nanjing Normal University, Qixia District, Nanjing, 210023, China ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: The aromatic amino acid biosynthesis pathway, together with its downstream branches, represents one of the Aromatic amino acid biosynthesis most commercially valuable biosynthetic pathways, producing a diverse range of complex molecules with many Shikimate pathway useful bioactive properties. Aromatic compounds are crucial components for major commercial segments, from De novo biosynthesis polymers to foods, nutraceuticals, and pharmaceuticals, and the demand for such products has been projected to Microbial production continue to increase at national and global levels. Compared to direct plant extraction and chemical synthesis, Flavonoids microbial production holds promise not only for much shorter cultivation periods and robustly higher yields, but Stilbenoids Benzylisoquinoline alkaloids also for enabling further derivatization to improve compound efficacy by tailoring new enzymatic steps. This review summarizes the biosynthetic pathways for a large repertoire of commercially valuable products that are derived from the aromatic amino acid biosynthesis pathway, and it highlights both generic strategies and spe- cific solutions to overcome certain unique problems to enhance the productivities of microbial hosts. -

Isotope Effects As Probes for Enzyme Catalyzed Hydrogen-Transfer Reactions

Molecules 2013, 18, 5543-5567; doi:10.3390/molecules18055543 OPEN ACCESS molecules ISSN 1420-3049 www.mdpi.com/journal/molecules Review Isotope Effects as Probes for Enzyme Catalyzed Hydrogen-Transfer Reactions Daniel Roston †, Zahidul Islam † and Amnon Kohen * Department of Chemistry, The University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA 52242, USA † These authors contributed equally to this work. * Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-319-335-0234. Received: 11 April 2013; in revised form: 30 April 2013 / Accepted: 3 May 2013 / Published: 14 May 2013 Abstract: Kinetic Isotope effects (KIEs) have long served as a probe for the mechanisms of both enzymatic and solution reactions. Here, we discuss various models for the physical sources of KIEs, how experimentalists can use those models to interpret their data, and how the focus of traditional models has grown to a model that includes motion of the enzyme and quantum mechanical nuclear tunneling. We then present two case studies of enzymes, thymidylate synthase and alcohol dehydrogenase, and discuss how KIEs have shed light on the C-H bond cleavages those enzymes catalyze. We will show how the combination of both experimental and computational studies has changed our notion of how these enzymes exert their catalytic powers. Keywords: kinetic isotope effects; Marcus-like models; alcohol dehydrogenase; thymidylate synthase; hydrogen tunneling 1. Introduction One of the most powerful tools in the chemist’s arsenal for studying reaction mechanisms and transition state structures is to measure kinetic isotope effects (KIEs). KIEs have become a pivotal source of information on enzymatic reactions, and a number of recent reviews have described the successes of KIEs in enzymology, from determining molecular mechanisms and transition state Molecules 2013, 18 5544 structures that are useful for drug design [1], to answering questions on the roles of nuclear quantum tunneling [2,3], electrostatics [4], and dynamic motions [5–8] in enzyme catalyzed reactions.