Ch. Rearick: French in Love And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Paris! Le Spectacle

Paris! Le Spectacle Saturday, November 18, 2017 at 8:00pm This is the 775th concert in Koerner Hall Anne Carrère, vocals Stéphanie Impoco, vocals Gregory Benchenafi, vocals Philippe Villa, musical direction & piano Guy Giuliano, accordion Laurent Sarrien, percussion & xylophone Fabrice Bistoni, bass Karine Soucheire, dance Jeff Dubourg, dance PROGRAM Paris medley Paris Les amants d’un jour La bohème Parisienne L'accordéoniste Yves Montand medley La foule Parlez-moi d’amour La goualante du pauvre Jean Comme d’habitude (My Way) J’ai deux amours Y’a d’la Joie medley Mon dieu INTERMISSION Moulin Rouge instrumental French Cancan medley Padam Que reste-t-il de nos amours? Charles Aznavour medley Mon amant de Saint-Jean Ne me quitte pas Jalousie Mon manège à moi Et maintenant Les petites femmes de Pigalle Milord Hymne à l’amour Non, je ne regrette rien La vie en rose Ça c’est Paris Les Champs-Élysées Musical arrangements: Gil Marsalla, Philippe Villa, Arnaud Fustélambezat This spectacular evening is a vibrant tribute to the greatest French songs of the post-war years and exports the charm and the flavour of Paris for the whole world to enjoy. The show transports us from Montmartre to the stages of the great Parisian cabarets of the time, presenting a repertoire of the greatest songs of Édith Piaf, Maurice Chevalier, Lucienne Boyer, Charles Trenet, Josephine Baker, Yves Montand, Charles Aznavour, Jacques Brel, and others. Story: Françoise, a young girl who dreams of becoming a famous artist in Paris, arrives in Montmartre. On her journey, she will cross paths with Édith Piaf and become her friend, confidante, and soul mate. -

Nova Bossa Repertoire

NOVA BOSSA REPERTOIRE JOBIM / BRAZILIAN JAZZ A Felicidade Dindi Agua de Beber Girl from Ipanema Aguas de Março (Waters of March) How Insensitive Amor em Paz (Once I Loved) O Morro Não Tem Vez (Favela) Bonita One Note Samba Brigas Nunca Mais Só Danço Samba Chega de Saudade Triste Corcovado (Quiet Nights) Wave Desafinado BOSSA NOVA / MPB Aquele Um - Djavan Ladeira da Preguiça - Elis Regina A Flor e o Espinho - Leny Andrade Lobo Bobo - João Gilberto Aquarela do Brasil (Brazil) - João Gilberto Maçã do Rosto - Djavan (Forró) A Rã - João Donato Mas Que Nada - Sergio Mendes Bala Com Bala - Elis Regina Maria das Mercedes - Djavan Berimbau - Baden Powell O Bêbado e a Equilibrista - Elis Regina Capim - Djavan O Mestre Sala dos Mares - Elis Regina Chove Chuva - Sergio Mendes O Pato - João Gilberto Casa Forte - Elis Regina (baião) Reza - Elis Regina Doralice - João Gilberto Rio - Leny Andrade É Com Esse Que Eu Vou - Elis Regina Serrado - Djavan Embola Bola - Djavan Telefone - Nara Leão Estate (Summer) - João Gilberto Tristeza - Beth Carvalho Fato Consumado - Djavan Vatapá - Rosa Passos Flor de Lis - Djavan Você Abusou JAZZ STANDARDS A Night in Tunisia Don't Get Around Much Anymore All of Me Fly Me To The Moon Almost Like Being in Love Gee, Baby, Ain't I Good to You As Time Goes By Green Dolphin Street Brother Can You Spare A Dime? Honeysuckle Rose Bye Bye Blackbird How High the Moon C'est Si Bon How Long Has This Been Going On? Dearly Beloved I Could Write A Book Do Nothing Til You Hear from Me I Only Have Eyes for You 1 I Remember You Save Your -

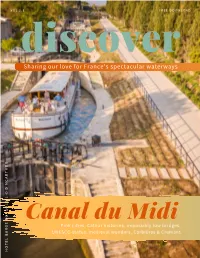

Canal Du Midi Waterways Guide

V O L 2 . 1 F R E E D O W N L O A D discover Sharing our love for France's spectacular waterways R U H T R A C M D © L I E L O S I O R Canal du Midi E G Pink cities, Cathar histories, impossibly low bridges, R A UNESCO status, medieval wonders, Corbières & Cremant B L E T O H P A G E 2 Canal du Midi YOUR COMPLETE GUIDE TO FRANCE'S MOST POPULAR WATERWAY Introducing the Canal du Midi Canal du Midi essentials Why visit the Canal du Midi? Where's best to stop? How to cruise the Canal du Midi? When to go? Canal du Midi top tips Contact us Travelling the magical Canal du Midi is a truly enchanting experience that will stay with you forever. It’s a journey whose every turn brings spectacular beauty that will leave you breathless. It’s an amazing feat of engineering whose elegant ingenuity will enthral you. It’s a rich and fertile region known for superb local produce, fabulous cuisine and world class wine. So, no matter how you choose to explore the Canal du Midi, by self-drive boat or hotel barge, just make sure you’re prepared to be utterly enchanted. Ruth & the team H O T E L B A R G E S A R A P H I N A P A G E 3 INTRODUCING THE CANAL DU MIDI The Canal du Midi runs from the city of Toulouse to It was the Romans who first dreamt of connecting the Mediterranean town of Sète 240km away. -

Photojournalism

ASSOCIATION VISA POUR L’IMAGE - PERPIGNAN Couvent des Minimes, 24, rue Rabelais - 66000 Perpignan tel: +33 (0)4 68 62 38 00 e-mail: [email protected] - www.visapourlimage.com FB Visa pour l’Image - Perpignan @visapourlimage PRESIDENT RENAUD DONNEDIEU DE VABRES rd VICE-PRESIDENT/TREASURER PIERRE BRANLE AUGUST 28 TO SEPTEMBER 26, 2021 COORDINATION ARNAUD FELICI & JÉRÉMY TABARDIN ASSISTANTS (COORDINATION) CHRISTOPHER NOU & NATHAN NOELL PRESS/PUBLIC RELATIONS 2e BUREAU 18, rue Portefoin - 75003 Paris INTERNATIONAL FESTIVAL OF tel: +33 (0)1 42 33 93 18 e-mail: [email protected] 33 www.2e-bureau.com Instagram & Twitter@2ebureau DIRECTOR GENERAL, COORDINATION SYLVIE GRUMBACH MANAGEMENT/ACCREDITATIONS VALÉRIE BOURGOIS PRESS RELATIONS MARTIAL HOBENICHE, DANIELA JACQUET ANNA ROUFFIA PHOTOJOURNALISM FESTIVAL MANAGEMENT Program subject to change due to Covid-19 health restrictions IMAGES EVIDENCE 4, rue Chapon - Bâtiment B - 75003 Paris tel: +33 (0)1 44 78 66 80 e-mail: [email protected] / [email protected] FB Jean Francois Leroy Twitter @jf_leroy Instagram @visapourlimage DIRECTOR GENERAL JEAN-FRANÇOIS LEROY EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR DELPHINE LELU COORDINATION CHRISTINE TERNEAU ASSISTANTJEANNE RIVAL SENIOR ADVISOR JEAN LELIÈVRE SENIOR ADVISOR – USA ELIANE LAFFONT SUPERINTENDENCE ALAIN TOURNAILLE TEXTS FOR SCREENINGS, PRESENTATIONS & RECORDED VOICE - FRENCH PAULINE CAZAUBON “MEET THE PHOTOGRAPHERS” MODERATOR CAROLINE LAURENT-SIMON BLOG & “MEET THE PHOTOGRAPHERS” CO-MODERATOR VINCENT JOLLY PROOFREADING OF FRENCH TEXTS & -

Ê K-Jîxbôflô:⁄Ýè

120753bk Trenet2 16/2/04 10:50 AM Page 2 13. Le soleil et la lune 2:26 18. Le retour des saisons 3:09 The Naxos Historical labels aim to make available the greatest recordings of the history of recorded (Charles Trenet) (Charles Trenet-Lasry) music, in the best and truest sound that contemporary technology can provide.To achieve this aim, With Wal-Berg's Orchestra Orchestra conducted by Albert Lasry Naxos has engaged a number of respected restorers who have the dedication, skill and experience Columbia DF 2667, mx CL 7144-1 Columbia BF 193, mx CL 8293-1 to produce restorations that have set new standards in the field of historical recordings. Recorded 27 October 1939 Recorded 7 January 1947 14. Mam'zelle Clio 2:43 19. Marie, Marie 2:51 (Charles Trenet) (Charles Trenet–Léo Chauliac) Also available from Naxos Nostalgia With Wal-Berg's Orchestra Orchestra conducted by Albert Lasry Columbia DF 2668, mx CL 7145-1 Columbia BF 107, mx CL 8295-1 Recorded 27 October 1939 Recorded 7 January 1947 15. Verlaine 3:23 20. Coquelicot 3:01 (Charles Trenet–Paul Verlaine) (Charles Trenet) Charles Trenet et Le Jazz de Paris Orchestra and Chorus conducted by Columbia DF 2800, mx CL 7399-1 Albert Lasry Recorded 31 January 1941 Columbia DF 3210, mx CL 8495-1ER 16. Terre 2:34 Recorded 19 January 1948 (Charles Trenet) All selections sung in French Charles Trenet et Le Jazz de Paris All titles recorded in Paris Columbia DF 2800, mx CL 7400-2 8.120523* 8.120553 8.120558 Recorded 31 January 1941 Transfers & Production: David Lennick 17. -

Maisons Des Illustres En Occit

Drac Occitanie | direction régionale des affaires culturelles Maisons des Illustres en Occitanie La région Occitanie possède 23 lieux labellisés "Maisons des Illustres" dont la vocation est de conserver et transmettre la mémoire des personnalités qui les ont habitées. Ariège Maison natale de Pierre Bayle Pierre Bayle (1647-1708). Rue principale Philosophe français adepte d’un rationalisme 09130 Carla-Bayle critique et moral, inspirateur des Lumières. Tél. 05 61 68 42 92 [email protected] www.maison-pierre-bayle.com Maison natale d'Aristide Bergès Aristide Bergès (1833-1904). Espace Aristide Bergès Industriel, ingénieur et inventeur de la houille Chemin des Papeteries blanche. 09190 Lorp-Sentaraille Tél. 05 61 66 13 97 [email protected] www.aab.asso.fr/maisonnatale.htm Aude Maison des Mémoires - Joë Bousquet Joë Bousquet (1897-1950). 53 rue de Verdun Poète. 11000 Carcassonne Tél. 04 68 72 50 83 [email protected] www.garae.fr/ Maison natale de Charles Trenet Charles Trenet (1913-2001). 13, avenue Charles Trenet Auteur, compositeur, interprète. 11100 Narbonne Tél. 04 68 90 30 65 [email protected] Gard Maison de Gaston Doumergue Gaston Doumergue (1863-1937). Place Gaston Doumergue Homme d’État, élu président de la République 30670 Aigues-Vives en 1924. Tél. 04 66 73 79 95 [email protected] http://amisdedoumergue.free.fr/Gaston_Doumergue/Gasto n_Doumergue.html Musée du Désert Pierre Laporte dit « Rolland » (1680-1704). Le Mas Soubeyran Chef camisard. 30140 Mialet Tél. 04 66 85 02 72 [email protected] www.museedudesert.com/article5684.html Maisons des Illustres 1/4 janvier 2020 Drac Occitanie | direction régionale des affaires culturelles Château d'Espeyran Guillaume, Guy et Frédéric Sabatier. -

Résumés Des Interventions Conférences

Résumés des interventions Conférences Yves CHARNET Un fantôme qui chante : hantises de Charles Trenet Un ange du bizarre échappé de quelque histoire fantastique… Ç’aura d’abord été, pour moi, cet être chimérique. De la transmission de sa légende par ma mère jusqu’à ma propre découverte du Fou chantant dans ses œuvres. C’est au début des années 70 que, au siècle dernier, se joue cette scène capitale. Ma rencontre intime avec Charles Trenet. Je vais avoir 10 ans. Lui 57. C’est mon âge aujourd’hui. Pour me demander de quoi ce chanteur-poète est-il le nom. Dans ma vocation de prosateur à l’écoute de ces rengaines qui me redisent dans leur refrain ces mots qui me font à la fin de la peine. Quelles fêlures dissimule le créateur de « Y a d’la joie ». Quelle mélancolie secrète. Celui pour qui chanter c’était, du même geste, hanter fut, pour le petit garçon de Nevers, ce revenant sous les masques duquel le monstre sacré revient à la chanson. Avec ce fabuleux album de 1971 significativement intitulé Fidèle. Mon Trenet c’est, pour toujours, le compositeur de la chanson numéro 5. « Le Revenant ». C’est de cette double hantise dont je voudrais, à l’occasion de cette carte blanche, essayer de parler. De cette présence spectrale du chanteur dans ma propre vie comme des obsessions propres à Charles Trenet dans son identification paradoxale à la figure du fantôme qui chante. Que reste-t-il de tout cela ? De cette aventure délirante souvent hallucinée… Dominic DAUSSAINT « Dîner avec un ami » : rencontres autour d’un projet de film documentaire J’ai fait la connaissance de Charles Trenet en 1987. -

Charles Trenet UN GENRE EN SOI 1913–2001 « La Nouvelle Génération N’Ose Plus Dire Qu’Elle Fait Des Chansons : on Fait Des Titres

Charles Trenet UN GENRE EN SOI 1913–2001 « La nouvelle génération n’ose plus dire qu’elle fait des chansons : on fait des titres. Je ne sais pas s’ils sont cotés en Bourse. » Charles Trenet TRENET EN 20 titres 1937 « Je chante », C’est le 25 mars 1938 qu’il débuta « Fleur bleue » de plain-pied pour un « seul en scène » 1938 retentissant à l’ABC, en première partie « Y’a d’la joie », de Lys Gauty – un mois auparavant, « La Polka du roi », « Boum ! » Maurice Chevalier, l’insigne vedette qui avait accepté l’une de ses compositions, 1939 « Ménilmontant », « Y’a d’la joie » (1936), l’y avait convié afin « Le Soleil et la Lune », de le présenter à son public. Ce soir du « Mam’zelle Clio » 25 mars, répondant aux exhortations du 1938 public trépignant, au lieu de chanter deux « La Romance de Paris » chansons, Trenet en avait enchaîné cinq. 1942 Les jours d’après, la presse relatait cet « Débit de l’eau », engouement phénoménal – Le Petit Pari- débit de lait », sien, sous la plume de Louis-Léon Martin : 1946 « Il s’est passé une manière d’événement « La Mer » vendredi dernier, à l’ABC. Un poète du 1950 tour de chant s’y est révélé dans une at- « Mes jeunes années » mosphère d’enthousiasme unanime […] » ; 1951 Le Figaro, sous celle d’André Warnod : « L’Âme des poètes », « Dans les pharmacies », « Charles Trenet, un tout jeune homme, « La Folle Complainte » À ses débuts, coiffé de son blond et rose, vigoureux, une vivacité, légendaire chapeau. 1952 une ardeur, une santé de jeune animal « La Jolie Sardane » en liberté. -

Pass Monumentale Narbonne 2021

MUSÉES MONUMENTS PASS MONUMENTALE NARBONNE 2021 16 VERS VERS CARCASSONNE, LA MAISON NATALE TOULOUSE DE CHARLES TRENET 8 Boulevard Maréchal Joffre 9 VERS PERPIGNAN, Boulevard Frédéric Mistral GARE SNCF, L’ESPACE DE LIBERTÉ, VERS LE SITE L’AUTOROUTE A9 VERS COURSAN, BÉZIERS ARCHÉOLOGIQUE NARBONNE SUD DU CLOS DE Rue Jean Jaurès LA LOMBARDE Rue de l’ancienn Boulevard Marcel Sembat e porte neuve Rue Voltaire Rue Chennebier 7 Place Rue du Lion d’Or des 5 Rue Dupleix Carmes Place Foch Maréchal Avenue Rue de la Parerie Rue Arago Salengro Rue du Capitol Quai Dillon 15 Rue Fabert Rue Gustave Fabre Rue des 3 Moulins 12 Canal de la Robine Rue de l’Hôtel Dieu 4 Rue A. Gauthier 6 Rue de l’Etoile Rue Rabelais Rue Bons Enfants Rue Marceau 2 Rue Hoche Rue de l’Ancienne Porte de Béziers Rue des 3 Pigeons 1 Rue Droite Rue Bonnel Boulevard du Docteur Lacroix Faure H. Rue 13 Rue Violet le Duc Place Cassaignol Rue Droite 3 Rue Michelet Rue Cabirol Rue Baudin Rue Crémieux Rue Rue Garibaldi Rue Raspail Rue Pont des Marchands Rue de l’Acien Courrier Place Rue Jean-Louis Longuet Rue de la Monnaie Rue Gabriel Pelouze Thérèse & Léon Rue du Luxembourg Blum Rue Louis Blanc Rue D. Rochereau Rue M. Coural Rue Francis Marcero Canal de la Robine Rue Garibaldi Rue Dugommier Rue de Belfort Rue du Docteur ROux Cours Mirabeau Boulevard Général De Gaulle Cours de la République Rue du Jeu de Paume Rue Niquet Palais Place Rue R. Bach Emile de justice Digeon Place de Verdun Rue Benet O Rue Paul Laffont Rue La Major N 10 Rue Emile Zola Rue Litté S 11 Boulevard Général De Gaulle 14 E Boulevard du Docteur Ferroul VERS NARBO VIA Boulevard Gambetta NARBONNE ARENA Pont de la Liberté LE PARC DES SPORTS A9 14 gratuit VERS NARBO VIA NARBONNE ARENA LE PARC DES SPORTS, LES PLAGES, AUTOROUTE A9, NARBONNE EST 1. -

Preface and Acknowledgments

Preface and Acknowledgments In 1994 I received a Fulbright grant to join a research group at the Centre national de la recherche scientifique (CNRS) in Paris to study French musi- cal life during the Second World War. I arrived in August to a city celebrat- ing the fiftieth anniversary of France’s liberation from German occupation. I assumed that, in exploring the wartime activities of French composers, I would be conducting historical research—writing a case study, as it were, of music, politics, and national identity. Yet, at a Fulbright reception before the research group’s first meeting, two elderly French music lovers insisted to me that no French music had been performed in wartime France. The only music they had heard in occupied Paris, they informed me, was German music played by German military bands. At the same time, French radio stations were marking the anniversary of the liberation by airing com- memorative broadcasts of wartime recordings by French ensembles, inter- spersed with interviews of aging French musicians about their wartime experiences. This startling juxtaposition of denial and homage was the first of several indications that the highly charged circumstances of the Second World War in France—the swift defeat by the German army and the humiliating armistice with Hitler in June 1940, the ordeal of foreign occu- pation, the moral complexities of France’s wartime Vichy regime, and the unresolved ambiguities of the French Resistance—were still a matter of lively national debate. This book addresses three misconceptions about music in France during the Second World War. The first, expressed to me by the elderly music lov- ers at the 1994 Fulbright reception, is that French music and musicians played a negligible role in the cultural life of wartime France. -

Steve Ross Press

Steve Ross Press STEVE ROSS - C'MON AND HEAR: AN IRVING BERLIN JULY 4th CELEBRATION Birdland, NY A themed evening with Steve Ross is as illuminating as it is entertaining. With cards-face-up fidelity, original embellishment, and the kind of indisputable panache that never sacrifices emotion for sophistication, Ross tonight offers a high-spirited celebration of Irving Berlin, “Russia’s best export after vodka.” As exemplified by a jaunty “Alexander’s Ragtime Band,” Ross’ lucid musicianship, aided by the excellent Jered Egan on bass, is more effective than a full band in capturing the intention of Berlin’s of-the-people oeuvre. The pianist effortlessly delivers light, tangy ragtime. Selective history and anecdotes act as bridges, not filler. Composer/lyricist Israel Isidore Baline (1888 -1989) fled a Russian pogrom, landing on New York’s Lower East Side. After stints as a singing waiter and song plugger, he began to write in earnest, catching ragtime fever. Ross describes the genre as “rhythms that came up the Mississippi to sit on marching tempo,” adroitly demonstrating with “Play a Simple Melody.” We’re treated to excerpts from several vivacious songs, including a percussive “When the Midnight Choo-Choo Leaves for Alabam”’ that appears to have fancy footwork. “I Love a Piano,” one of our host’s favorites, is as dancey as it gets. Ross is able to make exuberanceeloquent. Higher octaves arrive quiet-difficult and effective. “Mandy” is equally infectious. “...so don’t you linger...” he sings boyishly, pointing at/warning the audience. Gestures come easily tonight, drawing us in. “When I Lost You,” Berlin’s first ballad, written upon the devastating, post-honeymoon death of his bride, is melodic, yet profound in its grief: “I lost the sunshine and roses/I lost the heavens so blue/I lost the beautiful rainbow/I lost the morning dew....” “Say It Isn’t So”—moving like chiffon and marabou, and a smoky, sotto voce “How Deep Is the Ocean? (How High Is the Sky)” show mastery of melancholy ardor. -

Four Exquisite Men Will Escort You on a Thrilling Joyride About LOVE! Prepare to Be Swept Away … This Is One French Kiss You Won't Want to Miss!

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE SINGAPORE, September 2013 Four exquisite men will escort you on a thrilling joyride about LOVE! Prepare to be swept away … This is one French Kiss you won't want to miss! A French Kiss in Singapore is a one-of-a-kind musical revue about love, the perfect show to warm your hearts before Christmas! Brought to you by the same team as the sold-out ‘A Singaporean in Paris’, this brand new revue illustrates the humorous, touching and capricious nature of love with a true Singaporean flavour. Hossan Leong (The Hossan Leong Show, La Cage), George Chan (December Rains, A Singaporean in Paris), Linden Furnell (Edges, Next to Normal) and Robin Goh (Happy Robin, Crazy Christmas) will sing, dance and charm their way into your hearts with this musical treat celebrating LOVE: the one two people share but also the love for one’s country, relatives and lost friends… They will make you (re-)discover love songs from four of France's most beloved contemporary songwriters and singers: - Charles Aznavour – ‘the Performer of the Century’, named as such by CNN - Serge Gainsbourg – the word and rhythm Magician, excelling in playful double-meanings; both adored and hated (and banned in many countries) for his provocative lyrics - Jacques Brel – the life lover Incarnation, internationally renowned for his powerful and striking lyrics, strong sarcasm and his enormous generosity - Charles Trenet – the Fou Chantant/Singing Madman, who made all generations even unknowingly sing ‘La Mer/Beyond the Sea’ (‘Finding Nemo’ soundtrack) These four artists have been a source of inspiration for generations of international stars: Sinatra, Liza Minnelli, David Bowie, Marlene Dietrich, Sting, Robbie Williams, Westlife, to more recently Placebo, Franz Ferdinand, Jarvis Cooker, Portishead, The Rakes….who all performed their songs in English.