Guidelines for Spiritual Reading from C.S. Lewis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introducing CS Lewis

Volume 1 Issue 3 Article 7 January 1972 Introducing C.S. Lewis: Sincerity Personified Kathryn Lindskoog Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythpro Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Lindskoog, Kathryn (1972) "Introducing C.S. Lewis: Sincerity Personified," Mythcon Proceedings: Vol. 1 : Iss. 3 , Article 7. Available at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythpro/vol1/iss3/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Mythopoeic Society at SWOSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mythcon Proceedings by an authorized editor of SWOSU Digital Commons. An ADA compliant document is available upon request. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Mythcon 51: The Mythic, the Fantastic, and the Alien Albuquerque, New Mexico • Postponed to: July 30 – August 2, 2021 Abstract An overview of C.S. Lewis’s life, primarily based on Surprised by Joy and Letters, covering the entire period from his birth to death with special emphasis on his education and conversion. Includes personal reminiscences of the author’s own meeting with him in 1956. This is the first chapter of Lindskoog’s biography of Lewis. Keywords Lewis, C.S.— Biography; Lewis, C.S.—Personal reminisences This article is available in Mythcon Proceedings: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythpro/vol1/iss3/7 Dnt:r<onacfnGLindskoog: Introducing C.S. Lewis:ml Sincerity ~ Personified l!ewfs= sfncer<ft:J! per<sont-i:ten by Kathryn Lindskoog "lie struck me as the most thoroughly converted for the distant green hills on the horizon. In contrast, man I ever met.• Walter Hooper they had some dazzling sandy summer days at the beach; C. -

“The Imitation of Christ” 1 John 3:1-7

Aaron Coyle-Carr 11:00 service Wilshire Baptist Church 15 April, 2018 Dallas, Texas “The Imitation of Christ” 1 John 3:1-7 A little book called The Imitation themselves, just as he is pure.” of Christ is perhaps the most And then later on in verse seven, popular piece of devotional “everyone who does what is material in all of Christian right is righteous, just as he is history, apart from the Bible, of righteous.” It’s pretty clear that course. First John believes that the beloved community, the church, Written in the early 1400s by a is made up of those who spend Dutch monk named Thomas, the their lives imitating Jesus. It is book begins like this: the sincerest form of flattery, after all. “‘He that followeth Me, walketh not in darkness,’ saith the Lord. And there’s some powerful truth These are the words of Christ, by to this idea of imitation. which we are taught how we Elsewhere in the New ought to imitate his life and Testament, Paul asks the church manners, if we would truly be at Corinth to be imitators of him, enlightened, and delivered from even as he imitates Christ. We all blindness of heart.” 1 should be imitators of Christ, but I worry that, in the modern For Thomas, disillusioned by the world especially, the idea of material excess and superstition imitation doesn’t go nearly far of the medieval church, the key enough. to all of Christian spirituality was pretty basic: being a faithful Almost fifteen years ago, a Christian simply meant imitating landmark project called “The the life of Jesus Christ. -

A Report of the House of Bishops' Working Party on Women in the Episcopate Church Ho

Women Bishops in the Church of England? A report of the House of Bishops’ Working Party on Women in the Episcopate Church House Publishing Church House Great Smith Street London SW1P 3NZ Tel: 020 7898 1451 Fax: 020 7989 1449 ISBN 0 7151 4037 X GS 1557 Printed in England by The Cromwell Press Ltd, Trowbridge, Wiltshire Published 2004 for the House of Bishops of the General Synod of the Church of England by Church House Publishing. Copyright © The Archbishops’ Council 2004 Index copyright © Meg Davies 2004 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or stored or transmitted by any means or in any form, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system without written permission, which should be sought from the Copyright Administrator, The Archbishops’ Council, Church of England, Church House, Great Smith Street, London SW1P 3NZ. Email: [email protected]. The Scripture quotations contained herein are from the New Revised Standard Version Bible, copyright © 1989, by the Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the USA, and are used by permission. All rights reserved. Contents Membership of the Working Party vii Prefaceix Foreword by the Chair of the Working Party xi 1. Introduction 1 2. Episcopacy in the Church of England 8 3. How should we approach the issue of whether women 66 should be ordained as bishops? 4. The development of women’s ministry 114 in the Church of England 5. Can it be right in principle for women to be consecrated as 136 bishops in the Church of England? 6. -

Imitation of Christ-Layout-12072017.Indd

BOOK ONE Practical advice about the spiritual life 1. we must take christ for our model, and despise the shams of earth He who follows me can never walk in darkness,1 our Lord says. Here are words of Christ, words of warning; if we want to see our way truly, never a trace of blindness left in our hearts, it is his life, his character, we must take for our model. Clearly, then, we must make it our chief business to train our thoughts upon the life of Jesus Christ. 2. Christ’s teaching—how it overshadows all the Saints have to teach us! Could we but master its spirit, what a store of hidden manna we should find there! How is it that so many of us can hear the Gospel read out again and again, with so little emotion? Because they haven’t got the spirit of Christ; that is why. If a man wants to understand Christ’s words fully, and relish the flavourSAMPLE of them, he must be one who is trying to fashion his whole life on Christ’s model. 3. Talk as learnedly as you will about the doctrine of the Holy Trinity, it will get you no thanks from the Holy Trinity if you aren’t humble about it. After all, it isn’t learned talk that saves a man or makes a Saint of him; only a life well lived can claim God’s friendship. For myself, I would sooner know what contrition feels like, than how to define it. Why, if you had the whole of Scripture and all the maxims of the philosophers at your finger-tips, what would be the use of it all, without God’s love and God’s grace? 1 Jn 8:12. -

Myth in CS Lewis's Perelandra

Walls 1 A Hierarchy of Love: Myth in C.S. Lewis’s Perelandra A Thesis Submitted to The Faculty of the School of Communication In Candidacy for the Degree of Master of Arts in English by Joseph Robert Walls May 2012 Walls 2 Liberty University School of Communication Master of Arts in English _______________________________________________________________________ Thesis Chair Date Dr. Branson Woodard, D.A. _______________________________________________________________________ First Reader Date Dr. Carl Curtis, Ph.D. _______________________________________________________________________ Second Reader Date Dr. Mary Elizabeth Davis, Ph.D. Walls 3 For Alyson Your continual encouragement, support, and empathy are invaluable to me. Walls 4 Contents Introduction......................................................................................................................................5 Chapter 1: Understanding Symbol, Myth, and Allegory in Perelandra........................................11 Chapter 2: Myth and Sacramentalism Through Character ............................................................32 Chapter 3: On Depictions of Evil...................................................................................................59 Chapter 4: Mythical Interaction with Landscape...........................................................................74 A Conclusion Transposed..............................................................................................................91 Works Cited ...................................................................................................................................94 -

The Mind and Will of Christ

THE HUMAN MIND AND WILL OF CHRIST By EDWARD YARNOLD ESUS WAS FULLY GOD and a real man. What did this mean in practice? In particular, what did it feel like to be both God and man? Was the sense of divinity so strong that Jesus' human J knowledge and will, though always present, were almost irrele- vant, as an electric light is useless and almost unnoticed in a room lit by strong sunlight? But this is virtual monophysitism, the heresy that Jesus' human nature was absorbed into his divinity. So perhaps the divine knowledge was sealed off from the human knowledge, so that at the divine level of his consciousness he was all-knowing, while at the human level he knew himself only as a man, beset by ignorance and doubt, though admittedly not sin. No, this is virtual nestorianism, the heresy that separates a human person in Christ from the divine. How then do we escape this dilemma? Professor Eric Mascall cast doubt upon the validity of any attempt to study Jesus' psychology, when he wrote: I am frankly amazed to find how often the problem of the incarnation is taken as simply the problem of describing the mental life and consciousness of the incarnate Lord, for this problem seems to me to be strictly insoluble. If I am asked to say what I believe it feels like to be God incarnate I can only reply that I have not the slightest idea and I should not expect to have it. 1 Nevertheless, there are good reasons for trying to penetrate as deeply as we can into this situation which is beyond our experience. -

ABSTRACT C.S. Lewis and the Conversion of the Aeneas Story In

ABSTRACT C.S. Lewis and the Conversion of the Aeneas Story in the Ransom Trilogy Katherine Grace Hornell Directors: Phillip J. Donnelly, Ph.D. and Alan Jacobs, Ph.D. Many readers of C. S. Lewis’s writing consider his science fiction trilogy an odd divergence from his expected repertoire. Though Lewis’ "Ransom Trilogy" proves distinctive among his works, the books grow from the same deep roots in classical and medieval literary traditions that inform his other writings. Drawing from Virgil, Dante, and Arthurian legend to structure his narrative, Lewis unites ancient myth and modern fiction in order to illumine Classical stories with Christian faith. This thesis considers how Lewis’s science fiction draws on the features of secondary epic and its attendant meanings that appear in the Aeneid and in Arthurian stories. Ultimately, Lewis models how contemporary writers can make old stories live anew. APPROVED BY DIRECTOR OF HONORS THESIS: __________________________________________________ Dr. Phillip J. Donnelly, Department of Great Texts APPROVED BY THE HONORS PROGRAM: ________________________________________________ Dr. Elizabeth Corey, Director DATE: __________________ C.S. LEWIS AND THE CONVERSION OF THE AENEAS STORY IN THE RANSOM TRILOGY A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Baylor University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Honors Program By Katherine Grace Hornell Waco, Texas August 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgments………………………………………………………....…………..iii Introduction…………………………………………………………………………….1 Chapter One: Out of the Silent Planet………………………………………………….4 Chapter Two: Perelandra……………………………………………………………..22 Chapter Three: That Hideous Strength………………………………………………..43 Conclusion…………………………………………………………………………….62 Bibliography…………………………………………………………………………..65 ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to express my sincere thanks both to Dr. Alan Jacobs and to Dr. Phillip J. -

Imitation of Christ'' in Christian Tradition: It's Missing Charismatic Emphasis

The "Imitation of Christ'' In Christian Tradition: It's Missing Charismatic Emphasis Jon Mark Ruthven, PhD Professor Emeritus, Regent University School of Divinity Part I Popular American culture, with its increasing focus on the spiritual,1 has generated a minor fad among teenagers: a WWJD? (“What Would Jesus Do?”) bracelet, which, while bouncing on the wrists of video game players and entangling the TV remote, clicking in gangsta rappers on MTV, seeks to draw its wearers toward an “imitation of Christ.” The WWJD bracelet expresses this more or less continuous tradition throughout church history to replicate the life of Christ, the tradition having deep but somewhat selectively attended roots in the New Testament itself. The devotional classics ranging from St Thomas à Kempis’s Imitatio Christi to Charles Sheldon’s In His Steps easily spring to mind as examples. But this notion of “following Jesus,” “discipleship” or “spirituality” calls up a historically conditioned set of restrictions on how far that “imitation” may be applied. Traditionally, aside from minor movements in the radical reformation or from certain restorationist groups, we understand that a replication of Jesus’ life is properly restricted to piety and ethics. Progress in biblical scholarship over two millennia has produced little movement on this front. A recent collection of academic essays, Patterns of Discipleship in the New Testament2 continues this tradition without any serious consideration of extending “discipleship” to any other areas of emulating Jesus, particularly to the miraculous.3 “Discipleship remains limited to “piety and ethics,” very much as is our present notion of “spiritual formation.” Because, in traditional theology, Jesus’ unique divinity was accredited by miracles, few Christians seriously attempted to replicate that performance in Jesus’ ministry. -

Thomas a Kempis’S Meditations on the Life of Lord, Let Me Know What I Ought to Know, Love What I Christ

KNOWING & DOING 1 A Teaching Quarterly for Discipleship of Heart and Mind This article originally appeared in the Summer 2005 issue of Knowing & Doing. C.S. LEWIS INSTITUTE PROFILES IN FAITH Thomas à Kempis (1380-1471) Author of history’s most popular devotional classic by Mark Galli, Managing Editor, Christianity Today ir Thomas More, England’s famous lord chancel- In the first treatise, “Useful reminders for the Slor under Henry VIII (and subject of the film A spiritual life,” Thomas lays out the primary require- Man for All Seasons) said it was one of the three ment for the spiritually serious: “We must imitate books everybody ought to own. Ignatius of Loyola, Christ’s life and his ways if we are to be truly en- founder of the Jesuits, read a chapter a day from it lightened and set free from the darkness of our own and regularly gave away copies as gifts. Methodist hearts. Let it be the most important thing we do, founder John Wesley said it was the best summary then, to reflect on the life of Jesus Christ.” of the Christian life he had ever read. The highest virtue, from which all other virtues They were talking about Thomas à Kempis’s The stem, is humility. Thomas bids all to let go of the illu- Imitation of Christ, the devotional classic that has sion of superiority. “If you want to learn something been translated into over 50 languages, in editions that will really help you, learn to see yourself as God too numerous for scholars to keep track of (by 1779 sees you and not as you see yourself in the distorted there were already 1,800 editions). -

Imitation of Christ: the Essence of a Catholic Mindset

Imitation of Christ: The essence of a Catholic mindset An image of Jesus is seen as Pope Francis greets a young woman during the World Youth Day welcoming ceremony in Blonia Park in Krakow, Poland, July 28. (CNS photo/Paul Haring) My wife and I recently finished watching a series on Netflix. As with any well-written show, I found myself engrossed in the characters and storyline. Throughout the day, I caught myself thinking about the latest plot twist and counting down the hours to when I could watch the next episode. In my last blog post, I wrote that “Catholics no longer think like Catholics. They think like Republicans, Democrats, liberals, conservatives, socialists, or secularists, but not as Catholics.” What is the key to restoring a Catholic way of thinking? In short, Catholics must seek to think like Jesus. And for me to think like Jesus, I need to replicate my experience of “binge watching” television shows such as “Lost,” “Downton Abbey,” “Blacklist” or more recently, “Stranger Things” by “binge meditating” on the life of Jesus. In the past, while commuting to work, sending an email, or watching the children, I was reviewing the latest episode of the show in the back of mind. As a Catholic, I need keep the mindfulness of a world beyond our present world, but replace the television show with the life of Jesus. In this process, my life will be less molded by the fictional characters of the newest hit show, and more by the life of Jesus. The concept of imitating Jesus has a rich tradition in Catholicism. -

Another Anglican View 11 C

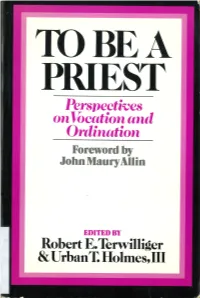

TO BE A PRIEST Perspectives on Vocation and Ordination edited by RaBERT E. TERWILLIGER URBAN T. HOLMES, ItrI with a Foreword by John Maury Allin A Crossroad Book THE SEABURY PRESS O NEW YORK The Seabury Press 815 Second Avenue New York, N.Y. 10017 Copyright O 1975 by The Seabury Press, Inc. Printed in the United States of America All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from the publisher, except for brief quotations in critical reviews and articles. LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CÄTALOGING IN PUBLIC.A,TION DAT.A Main entry under title: To be a priest. "A Crossroad book." Bibliography: p. 1. Priests-Addresses, essays, lectures. 2. Priesthood-Addresses, essays, lectures. I. Ter- wilÌiger, Robert E. II. Holmes, Urban Tigner, 1930- 8V662.T6 262'.r4 75-28248 ISBN 0-8164-2592-2 contents FOREWORD John Maurg AIIín rx c. PREFACE Robert E. Teruillíger and Urban T' Holmes be reproduced in any manner whatsoever ter, except for brief quotations in cri;ic; Pørt L What ís a Príest? 1. One Anglican View Robert E. TerwíIlíger 2. Another Anglican View 11 C. FitøSímons AIIíson 3. An Orthodox Statement 2L Thomas HoPko 4. A Roman Catholic Catechism 29 Quentín Quesnell Pørt IL The Príesthood ín the Bíble ønd Hístory 5. Priesthood in the History of Religions 45 loseph Kítagaua 6. The Priesthood of Christ 55 MEIes M' Bourke 7. Priesthood in the New Testament 63 ,UBLICATION DATA Louís Weil 8. Presbyters in the EarlY Church 7L MasseE H. ShePherd, Jr' 9. -

The Imitation of Christ

THE IMITATION OF CHRIST By JOHN ASHTON HE PROBLEM I want to tackle in this paper may be put in the following way. What is the point of contemplating or of prayerfully reflecting upon the life and teaching of Christ T as it is portrayed in the gospels? What does the christian hope - or what should he hope - to get out of this exercise? Why cannot he confine himself, as St Paul did, to attempting to assimilate into his own life the central mysteries of the christian message - God's revelation of himself to mankind through the passion, death and resurrection of his Son? St Paul succeeded in finding an answer to the question, What do the passion and resurrection mean to me and to others like me? We are so used to his answer that we tend to underestimate the difficulty of the question. Paul 'interiorized' Christ's passion and death by giving his own life (or recognizing in his own life) what Fr Yarnold has called 'a paschal shape'. By any standards this was an extraordinary intellectual and religious achievement. Why cannot we stop there? Why do we need to go further and enquire about or reflect upon the details of Christ's life ? The question may be put in another way: is it enough to think of Christ as man (as St Paul undoubtedly did), or must we be able to think of him as a man? And perhaps there is a third way of putting it too. Could christianity have dispensed with the synoptic gospels? Would it have been much the poorer, or even the same religion, without them? Some may detect a bultmannian ring in these questions; and they would be right.