A Mother Gorilla's Variable Use of Touch Toguide Her Infant

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Music Video As Black Art

IN FOCUS: Modes of Black Liquidity: Music Video as Black Art The Unruly Archives of Black Music Videos by ALESSANDRA RAENGO and LAUREN MCLEOD CRAMER, editors idway through Kahlil Joseph’s short fi lm Music Is My Mis- tress (2017), the cellist and singer Kelsey Lu turns to Ishmael Butler, a rapper and member of the hip-hop duo Shabazz Palaces, to ask a question. The dialogue is inaudible, but an intertitle appears on screen: “HER: Who is your favorite fi lm- Mmaker?” “HIM: Miles Davis.” This moment of Black audiovisual appreciation anticipates a conversation between Black popular cul- ture scholars Uri McMillan and Mark Anthony Neal that inspires the subtitle for this In Focus dossier: “Music Video as Black Art.”1 McMillan and Neal interpret the complexity of contemporary Black music video production as a “return” to its status as “art”— and specifi cally as Black art—that self-consciously uses visual and sonic citations from various realms of Black expressive culture in- cluding the visual and performing arts, fashion, design, and, obvi- ously, the rich history of Black music and Black music production. McMillan and Neal implicitly refer to an earlier, more recogniz- able moment in Black music video history, the mid-1990s and early 2000s, when Hype Williams defi ned music video aesthetics as one of the single most important innovators of the form. Although it is rarely addressed in the literature on music videos, the glare of the prolifi c fi lmmaker’s infl uence extends beyond his signature lumi- nous visual style; Williams distinguished the Black music video as a creative laboratory for a new generation of artists such as Arthur Jafa, Kahlil Joseph, Bradford Young, and Jenn Nkiru. -

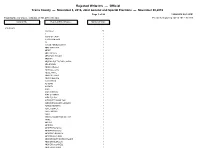

Rejected Write-Ins

Rejected Write-Ins — Official Travis County — November 8, 2016, Joint General and Special Elections — November 08,2016 Page 1 of 28 12/08/2016 02:12 PM Total Number of Voters : 496,044 of 761,470 = 65.14% Precincts Reporting 247 of 268 = 92.16% Contest Title Rejected Write-In Names Number of Votes PRESIDENT <no name> 58 A 2 A BAG OF CRAP 1 A GIANT METEOR 1 AA 1 AARON ABRIEL MORRIS 1 ABBY MANICCIA 1 ABDEF 1 ABE LINCOLN 3 ABRAHAM LINCOLN 3 ABSTAIN 3 ABSTAIN DUE TO BAD CANDIA 1 ADA BROWN 1 ADAM CAROLLA 2 ADAM LEE CATE 1 ADELE WHITE 1 ADOLPH HITLER 2 ADRIAN BELTRE 1 AJANI WHITE 1 AL GORE 1 AL SMITH 1 ALAN 1 ALAN CARSON 1 ALEX OLIVARES 1 ALEX PULIDO 1 ALEXANDER HAMILTON 1 ALEXANDRA BLAKE GILMOUR 1 ALFRED NEWMAN 1 ALICE COOPER 1 ALICE IWINSKI 1 ALIEN 1 AMERICA DESERVES BETTER 1 AMINE 1 AMY IVY 1 ANDREW 1 ANDREW BASAIGO 1 ANDREW BASIAGO 1 ANDREW D BASIAGO 1 ANDREW JACKSON 1 ANDREW MARTIN ERIK BROOKS 1 ANDREW MCMULLIN 1 ANDREW OCONNELL 1 ANDREW W HAMPF 1 Rejected Write-Ins — Official Travis County — November 8, 2016, Joint General and Special Elections — November 08,2016 Page 2 of 28 12/08/2016 02:12 PM Total Number of Voters : 496,044 of 761,470 = 65.14% Precincts Reporting 247 of 268 = 92.16% Contest Title Rejected Write-In Names Number of Votes PRESIDENT Continued.. ANN WU 1 ANNA 1 ANNEMARIE 1 ANONOMOUS 1 ANONYMAS 1 ANONYMOS 1 ANONYMOUS 1 ANTHONY AMATO 1 ANTONIO FIERROS 1 ANYONE ELSE 7 ARI SHAFFIR 1 ARNOLD WEISS 1 ASHLEY MCNEILL 2 ASIKILIZAYE 1 AUSTIN PETERSEN 1 AUSTIN PETERSON 1 AZIZI WESTMILLER 1 B SANDERS 2 BABA BOOEY 1 BARACK OBAMA 5 BARAK -

A Million Trees Offer Hope to Save the Gorillas' Home

issue 48 summer 2017 the gorilla organization A million trees offer hope to save the gorillas’ home Letter from The Gorilla Organization has helped the Virungas villagers in the Congo to plant more than a million trees to protect gorilla habitats and prevent This year’s 50th devastating floods. anniversary of The initiative was driven by Dian Fossey’s Gorilla Organization programme arrival in Africa manager Henry Cirhuza, reminds us how who brought the World Food far we have come Programme (WFP) on board to in the fight to save continue a tree-planting project gorillas from extinction. protecting the delicate ecosystem In the 1980s there were of Kahuzi-Biega National Park. just 250 mountain gorillas in the world The WFP provided more than and it was a daily fight to protect them. 269,000 tonnes of ‘Food for Work’ Today they are rising back towards a for the project’s beneficiaries who Beneficiaries receive training from Gorilla Organization staff thousand, and we are working with then plant out the saplings to communities across central Africa reforest land at the edge of the network of streams that prevent In 2014, Léontine Muduha to halt the decline of the three other park. flooding during the rainy seasons. witnessed first-hand the unforeseen gorilla subspecies. “This should mean people Over recent years, this delicate consequences of destroying the But there is still a gorilla-sized have less reason to go into or system has come under threat, with forest. When the heavy rains came, mountain to climb! Grauer’s (eastern even destroy the forest, which is forest destroyed for subsistence the River Nyalunkumbo was unable lowland) gorilla numbers have gone excellent news for the gorillas”, farming. -

Still Only a Theory? America's Continuing

Still Only a Theory? America’s Continuing Problem with Evolution Ken Miller Molecular Biology, Cell Biology, & Biochemistry Brown University 10/16/09 Sam Brownback We Live in Mike(Really) Huckabee Interesting Times Tom Tancredo I’m curious. Is there anybody on the stage that does not believe in evolution? Mike Huckabee: “If anybody wants to believe that they are the descendants of a primate, they are certainly welcome to do it.” Who’s to blame for humans being classified as primates? Not Charles Darwin. Carolus Linneaus: the father of modern scientific classifcation, and a creationist X “Deus creavit; Linneaus disposuit” TwoTwoEvolution StateFederal Elections isTrials an Issue GeorgiaKansas that Divides; ;Ohio PA Americans “If you believe in God, creation, & true science, vote for ” .... “If you believe in This textbook contains material on evolution. Debbie. Evolution is a theory, not a fact, regarding the origin of living things. This material should be approached with an open mind, evolution, abortion,studied carefully. and” critically & considered. sin, vote for her opponent Judgment Day What does “Intelligent Design” mean? • IDTheists, is the byproposition definition, that believe “design,” in a in the formtranscendent of outside intelligence, intelligent intervention, sometimes is requiredexpressed to as account a view for that the there origins is an of livingintelligent things. design to the universe. • This distinguishesBut thisID from is not more what is general considerationsmeant of meaning by ID. and purpose in the universe, and makes it a doctrine of special creation. 2004: The Dover (PA) school board votes for an “intelligent design” lesson in biology. The Dover Board followed a Discovery Institute playbook on ID, and purchased the textbook Of Pandas & People. -

Download File

Your Rights, Your World: The Power of Youth in the Age of the Sustainable Development Goals Prepared by: Rhianna Ilube, Natasha Anderson, Jenna Mowat, Ali Goldberg, Tiffany Odeka, Calli Obern, and Danny Tobin Kahane Program at the United Nations Disclaimer: This report was written by a seven member task force comprised of members of Occidental College at the United Nations program. For four months, participating students interned in various agency or permanent missions to the United Nations. As the authors are not official UNICEF staff members, this report in no way reflects UNICEF's views or opinions. Furthermore, this report in no way endorses the views or opinions of Occidental College. 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS: Foreword ……………………………………………………………………………………………….. p.4 Acknowledgements…………………………………………………………………………………….. p. 5 Executive Summary……………………………………………………………………………………… p. 6 Background ……………………………………………………………………………………………. Why this report is needed …………………………………………………………………… p. 6 Defining Key Concepts ……………………………………………………………………… p. 8 Methodology ……….……………………………………………………………………….. p. 9 The Case Studies …………………………………………………………………………………… High-Income: United Kingdom ………………………………………………………….. p. 11 Middle- Income: Colombia ……………………………………………………………….. p. 15 The Role of Youth to Advance Goal 13 on Climate Action for Colombia ……………… p. 16 Low-Income: Uganda ……………………………………………………………………… p. 21 Refugee Children: Education in Emergencies ……………………………………………. p. 26 Youth Voices: Fresh Ideas ………………………………………………………………………… p. 31 Building Awareness: Opportunities and -

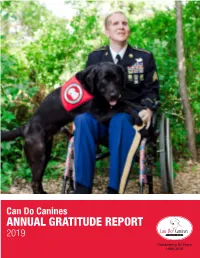

2019 Annual Report

Can Do Canines ANNUAL GRATITUDE REPORT 2019 ® Celebrating 30 Years 1989-2019 A Letter From Can Do Canines EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR ALAN PETERS Mission Annual Gratitude Report 2019 Can Do Canines is dedicated to & BOARD CHAIR MITCH PETERSON enhancing the quality of life for 3 A Letter From the Executive Director and Board Chair people with disabilities by creating 4 At a Glance Infographic Dear Friends, mutually beneficial partnerships 5 Client Stories with specially trained dogs. We are pleased to share this report of Can Do Canines’ accomplishments 8 Graduate Teams during 2019. Throughout these pages you’ll see our mission come to life through the stories and words of our graduates. You’ll witness the many 11 The Numbers people who have helped make Can Do Canines possible. And we hope you’ll Celebrating 12 Volunteers be inspired to continue your support. Vision 30 Years We envision a future in which every 16 Contributors We celebrated our 30th anniversary during 2019! Thirty years of service 1989-2019 to the community is a significant accomplishment. An anniversary video person who needs and wants an 25 Legacy Club Alan M. Peters and special logo were created and shared at events and in publications Executive Director assistance dog can have one. 26 Donor Policy throughout the year. Our 30th Anniversary Gala was made extra special by inviting two-time Emmy award winner Louie Anderson to entertain us. And enclosed with this report is the final part of the celebration: our booklet celebrating highlights of those 30 years. Values Those Who Served on the Most importantly, we celebrated our mission through action. -

Lucy Britt Masters

MOURNING AGAIN IN AMERICA: MEMORIAL DAY, MONUMENTS, AND THE POLITICS OF REMEMBRANCE Lucy Britt A thesis submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Political Science in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences. Chapel Hill 2017 Approved by: Susan Bickford Michael Lienesch Jeff Spinner-Halev © 2017 Lucy Britt ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Lucy Britt: Mourning Again in America: Memorial Day, Monuments, and the Politics of Remembrance (Under the Direction of Susan Bickford) The subjects and modes of mourning undertaken in public are consequential for past and continuing injustices because they indicate what a society cares about remembering and how. Holidays and monuments, as expressions of civil religion, affect how citizens read their history by rejecting or legitimating state violence and war in the future. Counter-narratives such as those from oppressed groups often emerge to challenge dominant narratives of civil religion. Close readers of civil religious ceremonies and markers such as Memorial Day and Confederate memorials should undertake a critical examination of the symbols’ historical meanings. I propose a politics of mourning that leverages the legal doctrine of government speech to reject impartiality and construct a public sphere in which different narratives of history are acknowledged but not all are endorsed. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES ....................................................................................................................... -

WILDLIFE CONSERVATION in the Field

WILDLIFE CONSERVATION IN THE FIELD Saving Nature Together MISSION Woodland Park Zoo saves animals and their habitats through conservation leadership and engaging experiences, inspiring people to learn, care and act. VISION Woodland Park Zoo envisions a world where people protect animals and conserve their habitats in order to create a sustainable future. As a leading conservation zoo, we empower people, in our region and around the world, to create this future, in ways big and small. CONTENTS Why Wildlife Conservation? .............4 Partners for Wildlife ............................8 Africa ................................................... 10 Central Asia ...................................... 12 Asia Pacific ......................................... 14 Living Northwest ............................... 22 Wildlife Survival Fund ...................... 36 Call to Action ..................................... 38 FIELD CONSERVatION at • We recognize that wildlife conservation ultimately WHY WILDLIFE CONSERVatION? WOODLAND PARK ZOO is about people, and long-term solutions will for example depend upon education, global health, • We carry out animal-focused projects that engage At Woodland Park Zoo, we believe that animals and habitats have intrinsic value, and that their poverty alleviation, and sustainable living practices. the public’s interest, contribute toward species existence enriches our lives. We also realize that animals and plants are essential for human Therefore, whenever advantageous, we include conservation, and leverage landscape-level -

Conference Program July 26-29, 2021 | Pacific Daylight Time 2021 Asee Virtual Conference President’S Welcome

CONFERENCE PROGRAM JULY 26-29, 2021 | PACIFIC DAYLIGHT TIME 2021 ASEE VIRTUAL CONFERENCE PRESIDENT’S WELCOME SMALL SCREEN, SAME BOLD IDEAS It is my honor, as ASEE President, to welcome you to the 128th ASEE Annual Conference. This will be our second and, almost certainly, final virtual conference. While we know there are limits to a virtual platform, by now we’ve learned to navigate online events to make the most of our experience. Last year’s ASEE Annual Conference was a success by almost any measure, and all of us—ASEE staff, leaders, volunteers, and you, our attendees—contributed to a great meeting. We are confident that this year’s event will be even better. Whether attending in person or on a computer, one thing remains the same, and that’s the tremendous amount of great content that ASEE’s Annual Conference unfailingly delivers. From our fantastic plenary speakers, paper presentations, and technical sessions to our inspiring lineup of Distinguished Lectures and panel discussions, you will have many learning opportunities and take-aways. I hope you enjoy this week’s events and please feel free to “find” me and reach out with any questions or comments! Sincerely, SHERYL SORBY ASEE President 2020-2021 2 Schedule subject to change. Please go to https://2021asee.pathable.co/ for up-to-date information. 2021 ASEE VIRTUAL CONFERENCE TABLE OF CONTENTS 2021 ASEE VIRTUAL CONFERENCE AND EXPOSITION PROGRAM ASEE BOARD OF DIRECTORS ................................................................................4 CONFERENCE-AT-A-GLANCE ................................................................................6 -

Journalism Class Introduces Humans of Jefferson College Senator Claire

Vol. 83 Issue 1 May 5, 2017 [email protected] the harbinger The student newspaper of Jefferson College since 1964 Senator Claire McCaskill Delivers Town Hall Journalism Class Introduces Meeting at Jefferson College Humans of Jefferson College by Nathan Imlay By Adam Riordan Are you familiar with Hu- All you have to do to register On April 12, Senator Claire is to sign a release form, allow us McCaskill held a town hall meet- mans of St. Louis or Humans of New York and wish that sort to take one picture of yourself (or ing at the Fine Arts Theater of send us a selfie of your own), and Jefferson College. More than of program would come to Jef- ferson College? Well, your wish a recording of the conversation 50 people attended to have the you have with the interviewer. Senator answer their questions. has been granted. Now, at Jefferson College in Once it's all done, we can share The vast majority of the crowd your exact details to the entire was friendly towards Senator Mc- Hillsboro, Missouri, the journal- ism course has now created their world by posting it on our Face- Caskill and many of the questions book page. With Humans of Jef- related to how the Democratic op- own unique human program with the Humans of Jefferson College. ferson College, this gives you all position could delay or halt pieces an opportunity to share anything of President Trump's agenda. With this program, this gives us the chances to talk to any student, that you desire to the whole cam- The Senator began with an pus and even the world. -

Adventuring with Books: a Booklist for Pre-K-Grade 6. the NCTE Booklist

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 311 453 CS 212 097 AUTHOR Jett-Simpson, Mary, Ed. TITLE Adventuring with Books: A Booklist for Pre-K-Grade 6. Ninth Edition. The NCTE Booklist Series. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, Ill. REPORT NO ISBN-0-8141-0078-3 PUB DATE 89 NOTE 570p.; Prepared by the Committee on the Elementary School Booklist of the National Council of Teachers of English. For earlier edition, see ED 264 588. AVAILABLE FROMNational Council of Teachers of English, 1111 Kenyon Rd., Urbana, IL 61801 (Stock No. 00783-3020; $12.95 member, $16.50 nonmember). PUB TYPE Books (010) -- Reference Materials - Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF02/PC23 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Annotated Bibliographies; Art; Athletics; Biographies; *Books; *Childress Literature; Elementary Education; Fantasy; Fiction; Nonfiction; Poetry; Preschool Education; *Reading Materials; Recreational Reading; Sciences; Social Studies IDENTIFIERS Historical Fiction; *Trade Books ABSTRACT Intended to provide teachers with a list of recently published books recommended for children, this annotated booklist cites titles of children's trade books selected for their literary and artistic quality. The annotations in the booklist include a critical statement about each book as well as a brief description of the content, and--where appropriate--information about quality and composition of illustrations. Some 1,800 titles are included in this publication; they were selected from approximately 8,000 children's books published in the United States between 1985 and 1989 and are divided into the following categories: (1) books for babies and toddlers, (2) basic concept books, (3) wordless picture books, (4) language and reading, (5) poetry. (6) classics, (7) traditional literature, (8) fantasy,(9) science fiction, (10) contemporary realistic fiction, (11) historical fiction, (12) biography, (13) social studies, (14) science and mathematics, (15) fine arts, (16) crafts and hobbies, (17) sports and games, and (18) holidays. -

RECEIVED Apri14, 2019 APR 0 5 2019

RECEIVED Apri14, 2019 APR 0 5 2019 Ben Haller BUREAU OF Kansas Department of Health and Environment ENVIRONMENTAL REMEDIATION Bureau of Environmental Remediation Remedial Section/Site Remediation Unit I 000 SW Jackson Street, Suite 420 Approved with Comments Topeka, Kansas 66612-1367 Date(s) /3 1-J '1-12.. ~ 2..D/1 RE: STF Suspected Waste Area Characterization Report Former Coastal Refinery, El Dorado, Kansas Dear Mr. Haller: On behalf of El Paso Merchant Energy-Petroleum Company (EPME-PC), Stantec Consulting Services, Inc. (Stantec) submits this South Tank Farm (STF) Suspected Waste Area Characterization report presenting data to further delineate and characterize a waste-like material reported in the September 2009 Third Phase Environmental Investigation Report (Third Phase Investigation Report) for the former Coastal Refinery (Site) located in El Dorado, Kansas (Figure I). This work is being conducted as part of the Corrective Action Plan (CAP) called for in the Site Final Corrective Action Decision (CAD, November 20 16). In addition, during soil grading/earthwork completed in December 2018 to improve surface water drainage from a former STF bermed area, a second suspected waste are.a was discovered. Both areas are identified on Figure 2, they were investigated, and the findings are presented in this letter report. NORTH STF SUSPECTED WASTE AREA The North STF suspected waste area was identified in 2008 during the Third Phase Investigation. History Sixteen shallow borings were advanced (STFPSB-0 I through STFPSB-16) as part of the Third Phase Investigation to assess the extent of the buried material during pipeline removal activities. The borings shown on Figure 3 were installed using a Geoprobe® rig to a maximum depth of eight feet, transecting the area.