Canadian Developing World

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Siriusxm-Schedule.Pdf

on SCHEDULE - Eastern Standard Time - Effective: Sept. 6/2021 ET Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri Saturday Sunday ATL ET CEN MTN PAC NEWS NEWS NEWS 6:00 7:00 6:00 5:00 4:00 3:00 Rewind The Doc Project The Next Chapter NEWS NEWS NEWS 7:00 8:00 7:00 6:00 5:00 4:00 Quirks & The Next Now or Spark Unreserved Play Me Day 6 Quarks Chapter Never NEWS What on The Cost of White Coat NEWS World 9:00 8:00 7:00 6:00 5:00 8:00 Pop Chat WireTap Earth Living Black Art Report Writers & Company The House 8:37 NEWS World 10:00 9:00 8:00 7:00 6:00 9:00 World Report The Current Report The House The Sunday Magazine 10:00 NEWS NEWS NEWS 11:00 10:00 9:00 8:00 7:00 Day 6 q NEWS NEWS NEWS 12:00 11:00 10:00 9:00 8:00 11:00 Because News The Doc Project Because The Cost of What on Front The Pop Chat News Living Earth Burner Debaters NEWS NEWS NEWS 1:00 12:00 The Cost of Living 12:00 11:00 10:00 9:00 Rewind Quirks & Quarks What on Earth NEWS NEWS NEWS 1:00 Pop Chat White Coat Black Art 2:00 1:00 12:00 11:00 10:00 The Next Quirks & Unreserved Tapestry Spark Chapter Quarks Laugh Out Loud The Debaters NEWS NEWS NEWS 2:00 Ideas in 3:00 2:00 1:00 12:00 11:00 Podcast Now or CBC the Spark Now or Never Tapestry Playlist Never Music Live Afternoon NEWS NEWS NEWS 3:00 CBC 4:00 3:00 2:00 1:00 12:00 Writers & The Story Marvin's Reclaimed Music The Next Chapter Writers & Company Company From Here Room Top 20 World This Hr The Cost of Because What on Under the NEWS NEWS 4:00 WireTap 5:00 4:00 3:00 2:00 1:00 Living News Earth Influence Unreserved Cross Country Check- NEWS NEWS Up 5:00 The Current -

News Deserts and Ghost Newspapers: Will Local News Survive?

NEWS DESERTS AND GHOST NEWSPAPERS: WILL LOCAL NEWS SURVIVE? PENELOPE MUSE ABERNATHY Knight Chair in Journalism and Digital Media Economics Will Local News Survive? | 1 NEWS DESERTS AND GHOST NEWSPAPERS: WILL LOCAL NEWS SURVIVE? By Penelope Muse Abernathy Knight Chair in Journalism and Digital Media Economics The Center for Innovation and Sustainability in Local Media School of Media and Journalism University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill 2 | Will Local News Survive? Published by the Center for Innovation and Sustainability in Local Media with funding from the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Office of the Provost. Distributed by the University of North Carolina Press 11 South Boundary Street Chapel Hill, NC 27514-3808 uncpress.org Will Local News Survive? | 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface 5 The News Landscape in 2020: Transformed and Diminished 7 Vanishing Newspapers 11 Vanishing Readers and Journalists 21 The New Media Giants 31 Entrepreneurial Stalwarts and Start-Ups 40 The News Landscape of the Future: Transformed...and Renewed? 55 Journalistic Mission: The Challenges and Opportunities for Ethnic Media 58 Emblems of Change in a Southern City 63 Business Model: A Bigger Role for Public Broadcasting 67 Technological Capabilities: The Algorithm as Editor 72 Policies and Regulations: The State of Play 77 The Path Forward: Reinventing Local News 90 Rate Your Local News 93 Citations 95 Methodology 114 Additional Resources 120 Contributors 121 4 | Will Local News Survive? PREFACE he paradox of the coronavirus pandemic and the ensuing economic shutdown is that it has exposed the deep Tfissures that have stealthily undermined the health of local journalism in recent years, while also reminding us of how important timely and credible local news and information are to our health and that of our community. -

Legacies of Biafra Conference Schedule - SOAS, University of London, April 21-22

H-AfrLitCine Legacies of Biafra Conference Schedule - SOAS, University of London, April 21-22 Discussion published by Louisa Uchum Egbunike on Monday, April 24, 2017 Legacies of Biafra Conference Schedule - April 21-22, SOAS, University of London Registration is to completed online at www.igboconference.com/tickets For further details about the conference, visit www.igboconference.com Conference Schedule: Thursday 20th April, Khalili Lecture Theatre, SOAS 6:00pm – 8:00pm Preconference Welcome, Film screening: Most Vulnerable Nigerians: The Legacy of the Asaba Massacres by Elizabeth Bird, followed by a Q & A session. Elizabeth Bird will introduce the documentary film and talk about her research and upcoming book about the Asaba Massacres. Film Screening: Onye Ije: The Traveller, An Igbo travelogue on the Umuahia War Museum & The Ojukwu Bunker produced by Brian C. Ezeike and Mazi Waga. The film will be introduced by the producers of the Documentary series, followed by a short Q & A Session. …………………………………………… FRIDAY, 21st APRIL 2017, Brunei Gallery Lecture Theatre & Suite, SOAS 8:30am Conference Registration Opens 9:30am Parallel Panels (A) A1 Panel: Revisiting Biafra A2 Panel: Writing Biafra (please scroll down for speaker details on the A Panels) 11:00am Parallel Panels (B) B1 Roundtable: Global Media and Humanitarian Responses to the Biafra War B2 Roundtable: Real Life Accounts of the War B3 Panel: Child Refugees of the Nigeria-Biafra war (please scroll down for speaker details on the B Panels ) 12:30pm Obi Nwakanma in Conversation with Olu Oguibe Citation: Louisa Uchum Egbunike. Legacies of Biafra Conference Schedule - SOAS, University of London, April 21-22 . -

Mass-Mediated Canadian Politics: CBC News in Comparative Perspective

Mass-Mediated Canadian Politics: CBC News in Comparative Perspective Blake Andrew Department of Political Science McGill University Leacock Building, Room 414 855 Sherbrooke Street West Montreal, QC H3A 2T7 blake.andrew at mcgill.ca *Paper prepared for the Annual General Meeting of the Canadian Political Science Association, Ottawa, Canada, May 27-29, 2009. Questions about news media bias are recurring themes of mainstream debate and academic inquiry. Allegations of unfair treatment are normally based on perceptions of inequality – an unfair playing field. News is dismissed as biased if people think that a political group or candidate is systemically advantaged (or disadvantaged) by coverage. When allegations of this nature surface, the perpetrator is usually one of three usual suspects: the media (writ large), a newsroom, or a medium (e.g. Adkins Covert and Wasburn 2007; D'Alessio and Allen 2000; Groeling and Kernell 1998; Niven 2002; Shoemaker and Cohen 2006). Headlines and stories are marshaled for evidence; yet the integrity of headlines as proxies for their stories is rarely considered as an avenue for testing and conceptualizing claims of media bias. It is common knowledge that headlines are supposed to reflect, at least to some degree in the space they have, the content that follows. Yet this myth has thus far received only sparse attention in social science (Althaus, Edy and Phalen 2001; Andrew 2007). It is a surprising oversight, partly because news headlines are clearly not just summaries. They also signal the importance of, and attempt to sell the news story that follows. The interplay of these imperatives is what makes a test of the relationship between headline news and story news particularly intriguing. -

Mapping Nigeria's Response to Covid-19 the Bold Ones

DIGITAL DIALOGUES A NATIONAL CONVERSATION: MAPPING NIGERIA’S RESPONSE TO COVID-19 POST-EVENT REPORT THE BOLD ONES: NIGERIAN COMPANIES REINVENTING FOR THE NEW NORMAL SPECIAL SUPPLEMENT JULY 2020 AGRIBUSINESS FINANCE MARKETS NIRSAL exists to create a handshake between the Agricultural Value Chain and the Financial Sector in order to boost productivity, food security and the profitability of agribusiness in Nigeria. At the heart of our strategy is the Credit Risk Guarantee (CRG) which enhances the flow of finance and investment into fixed Agricultural Value Chains by serving as a buffer that encourages investors to fund verified bankable projects. Working with financial institutions, farmer groups, mechanization service providers, logistics providers and other actors in the Value Chain, NIRSAL is changing Nigeria's agricultural landscape and delivering food security, financial inclusion, wealth creation and economic growth. THE NIGERIA INCENTIVE-BASED RISK SHARING SYSTEM FOR AGRICULTURAL LENDING De-Risking Agriculture Facilitating Agribusiness Office Address Lagos Office Plot 1581, Tigris Crescent CBN Building www.nirsal.com Maitama District Tinubu Square, Marina You u e Abuja, Nigeria Lagos, Nigeria @nirsalconnect NIRSAL, a Central Bank of Nigeria corporation. DIGITAL DIALOGUES A NATIONAL CONVERSATION: MAPPING NIGERIA’S RESPONSE TO COVID-19 POST-EVENT REPORT THE BOLD ONES: NIGERIAN COMPANIES REINVENTING FOR THE NEW NORMAL SPECIAL SUPPLEMENT Sponsors Moderators and Panelists ZAINAB PROF. AKIN IBUKUN DR. OBIAGELI ALIYU DR. DOYIN OLISA ENGR. -

Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2020

Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2020 Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2020 Nic Newman with Richard Fletcher, Anne Schulz, Simge Andı, and Rasmus Kleis Nielsen Supported by Surveyed by © Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism / Digital News Report 2020 4 Contents Foreword by Rasmus Kleis Nielsen 5 3.15 Netherlands 76 Methodology 6 3.16 Norway 77 Authorship and Research Acknowledgements 7 3.17 Poland 78 3.18 Portugal 79 SECTION 1 3.19 Romania 80 Executive Summary and Key Findings by Nic Newman 9 3.20 Slovakia 81 3.21 Spain 82 SECTION 2 3.22 Sweden 83 Further Analysis and International Comparison 33 3.23 Switzerland 84 2.1 How and Why People are Paying for Online News 34 3.24 Turkey 85 2.2 The Resurgence and Importance of Email Newsletters 38 AMERICAS 2.3 How Do People Want the Media to Cover Politics? 42 3.25 United States 88 2.4 Global Turmoil in the Neighbourhood: 3.26 Argentina 89 Problems Mount for Regional and Local News 47 3.27 Brazil 90 2.5 How People Access News about Climate Change 52 3.28 Canada 91 3.29 Chile 92 SECTION 3 3.30 Mexico 93 Country and Market Data 59 ASIA PACIFIC EUROPE 3.31 Australia 96 3.01 United Kingdom 62 3.32 Hong Kong 97 3.02 Austria 63 3.33 Japan 98 3.03 Belgium 64 3.34 Malaysia 99 3.04 Bulgaria 65 3.35 Philippines 100 3.05 Croatia 66 3.36 Singapore 101 3.06 Czech Republic 67 3.37 South Korea 102 3.07 Denmark 68 3.38 Taiwan 103 3.08 Finland 69 AFRICA 3.09 France 70 3.39 Kenya 106 3.10 Germany 71 3.40 South Africa 107 3.11 Greece 72 3.12 Hungary 73 SECTION 4 3.13 Ireland 74 References and Selected Publications 109 3.14 Italy 75 4 / 5 Foreword Professor Rasmus Kleis Nielsen Director, Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism (RISJ) The coronavirus crisis is having a profound impact not just on Our main survey this year covered respondents in 40 markets, our health and our communities, but also on the news media. -

Nigeria's Economic Reforms

Nigeria’s Economic Reforms Progress and Challenges Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala Philip Osafo-Kwaako Working Paper # 6 NIGERIA’S ECONOMIC REFORMS: PROGRESS AND CHALLENGES Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala Distinguished Fellow Global Economy and Development Program The Brookings Institution Philip Osafo-Kwaako Visiting Research Associate Global Economy and Development Program The Brookings Institution MARCH 2007 THE BROOKINGS INSTITUTION 1775 MASSACHUSETTS AVE., NW WASHINGTON, DC 20036 2 The authors are grateful to various colleagues, particularly members of the Nigerian Economic Team, for valuable comments and suggestions on various components of the recent reform program. Additional suggestions should be directed to [email protected]. About the Global Economy and Development Program The Global Economy and Development program at Brookings examines the opportunities and challenges presented by globalization, which has become a central concern for policymakers, business executives and civil society, and offers innovative recommendations and solutions in order to materially shape the policy debate. Global Economy and Development scholars address the issues surrounding globalization within three key areas: • The drivers shaping the global economy • The road out of poverty • The rise of new economic powers The program is directed by Lael Brainard, vice president and holder of the Bernard L. Schwartz Chair in International Economics. The program also houses the Wolfensohn Center for Development, a major effort to improve the effectiveness of national and international development efforts. www.brookings.edu/global The views expressed in this working paper do not necessarily reflect the official position of Brookings, its board or the advisory council members. © The Brookings Institution ISBN: 978-0-9790376-5-8 Contents List of Acronyms . -

World Bank Document

IDA and Africa: Partnering for Development IDA and Africa: Partnering for Development Sans Poverty One Dream. One Mission. www.worldbank.org FOCUS ON AFRICA - APRIL 2007, ISSUE 3 Public Disclosure Authorized Liberia | Ghana Celebrates | The World Bank in Africa| IDA in Africa| Ask the Expert| News Published by the North American Affairs team, Sans Poverty highlights World Bank projects, policies and programs. We aim to make it a concise, interesting and informative to read. We welcome your comments. Please email us at [email protected] or [email protected]. LIBERIA'S PRESIDENT AFFIRMS STRONG PARTNERSHIP WITH BANK, URGES WOMEN TO STRIVE FOR LEADERSHIP March 28, 2006— During her recent visit to the United States, and World Bank Headquarters in Washington, Liberian President Ellen Johnson-Sirleaf, hailed the strong partnership Liberia enjoys with the World Bank, Public Disclosure Authorized outlined some benchmarks for Liberia’s development goals, and urged women to strive for higher levels of responsibility and leadership. President Johnson-Sirleaf met with World Bank President Paul Wolfowitz, who pledged the Bank’s support for resolving the issue of Liberia’s debt to the Bank, and continued support for pre-arrears President Johnson-Sirleaf welcomed by clearance. President Wolfowitz | Photo:© World Bank “We are very pleased with the strong support which we are receiving from the Bank and President Wolfowitz,” she said. “The Bank is already a very strong partner with Liberia and is helping us in some of our Public Disclosure Authorized infrastructure work and the review of some of the concession agreement that will lead to better management of our own resources. -

Appendix 6 Board of Directors’ Response to the Recommendations Presented in the Ombudsmens’ Report

APPENDIX 6 BOARD OF DIRECTORS’ RESPONSE TO THE RECOMMENDATIONS PRESENTED IN THE OMBUDSMENS’ REPORT BOARD OF DIRECTORS of the CANADIAN BROADCASTING CORPORATION STANDING COMMITTEES ON ENGLISH AND FRENCH LANGUAGE BROADCASTING Minutes of the Meeting held on June 18, 2014 Ottawa, Ontario = by videoconference Members of the Committee present: Rémi Racine, Chairperson of the Committees Hubert T. Lacroix Edward Boyd Peter Charbonneau George Cooper Pierre Gingras Marni Larkin Terrence Leier Maureen McCaw Brian Mitchell Marlie Oden Members of the Committee absent: Cecil Hawkins In attendance: Maryse Bertrand, Vice-President, Real Estate, Legal Services and General Counsel Heather Conway, Executive Vice-President, English Services () Louis Lalande, Executive Vice-President, French Services () Michel Cormier, Executive Director, News and Current Affairs, French Services () Stéphanie Duquette, Chief of Staff to the President and CEO Esther Enkin, Ombudsman, English Services () Tranquillo Marrocco, Associate Corporate Secretary Jennifer McGuire, General Manage and Editor in Chief, CBC News and Centres, English Services () Pierre Tourangeau, Ombudsman, French Services () Opening of the Meeting At 1:10 p.m., the Chairperson called the meeting to order. 2014-06-18 Broadcasting Committees Page 1 of 2 1. 2013-2014 Annual Report of the English Services’ Ombudsman Esther Enkin provided an overview of the number of complaints received during the fiscal year and the key subject matters raised, which included the controversy about paid speaking engagements by CBC personalities, the reporting on results polls, the style of, and views expressed by, a commentator, questions relating to matters of taste, the coverage regarding the mayor of Toronto, and the website’s section for comments. She also addressed the manner in which non-news and current affairs complaints are being handled by the Corporation. -

An Exploratory Study of Global and Local Discourses on Social Media Regulation

Global Media Journal German Edition From the field An Exploratory Study of Global and Local Discourses on Social Media Regulation Andrej Školkay1 Abstract: This is a study of suggested approaches to social media regulation based on an explora- tory methodological approach. Its first aim is to provide an overview of the global and local debates and the main arguments and concerns, and second, to systematise this in order to construct taxon- omies. Despite its methodological limitations, the study provides new insights into this very rele- vant global and local policy debate. We found that there are trends in regulatory policymaking to- wards both innovative and radical approaches but also towards approaches of copying broadcast media regulation to the sphere of social media. In contrast, traditional self- and co-regulatory ap- proaches seem to have been, by and large, abandoned as the preferred regulatory approaches. The study discusses these regulatory approaches as presented in global and selected local, mostly Euro- pean and US discourses in three analytical groups based on the intensity of suggested regulatory intervention. Keywords: social media, regulation, hate speech, fake news, EU, USA, media policy, platforms Author information: Dr. Andrej Školkay is director of research at the School of Communication and Media, Bratislava, Slovakia. He has published widely on media and politics, especially on political communication, but also on ethics, media regulation, populism, and media law in Slovakia and abroad. His most recent book is Media Law in Slovakia (Kluwer Publishers, 2016). Dr. Školkay has been a leader of national research teams in the H2020 Projects COMPACT (CSA - 2017-2020), DEMOS (RIA - 2018-2021), FP7 Projects MEDIADEM (2010-2013) and ANTICORRP (2013-2017), as well as Media Plurality Monitor (2015). -

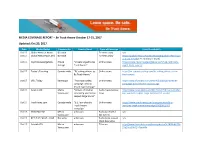

MEDIA COVERAGE REPORT – Be Truck Aware October 17-31, 2017 Updated: Oct 20, 2017

MEDIA COVERAGE REPORT – Be Truck Aware October 17-31, 2017 Updated: Oct 20, 2017 Date Media Outlet Community Header/Lead Type of Coverage Link (if available) Oct 17 Global News at Noon BC-wide TV news story n/a Oct 17 Global News Hours at 6 BC-wide TV news story https://globalnews.ca/video/3810220/global-news-hour- at-6-oct-17-4 (at 21:14 minute mark) Oct 17 MyPrinceGeorgeNow Prince “Drivers Urged to Be Online news https://www.myprincegeorgenow.com/59471/drivers- George Truck Aware” urged-truck-aware/ Oct 17 Today’s Trucking Canada-wide “BC asking drivers to Online news https://m.todaystrucking.com/bc-asking-drivers-to-be- Be Truck Aware” truck-aware Oct 17 CFJC Today Kamloops “Provincial safety Online news http://www.cfjctoday.com/article/592118/provincial- campaign aims to campaign-aims-lessen-road-carnage lessen road carnage” Oct 17 News 1130 Metro “Drivers of smaller Radio News/online http://www.news1130.com/2017/10/17/drivers-smaller- Vancouver cars being warned to news cars-warned-respect-large-commercial-trucks/ respect large trucks” Oct 17 TruckNews.com Canada-wide “B.C. launches Be Online news https://www.trucknews.com/transportation/b-c- Truck Aware launches-truck-aware-campaign/1003081520/ campaign” Oct 17 CKYE RED FM Metro unknown Radio (attended n/a Vancouver the event) Oct 17 97.3 THE EAGLE - CKLR Nanaimo unknown Radio (interviewed n/a Mark Donnelly) Oct 17 Fairchild TV Metro unknown TV news http://www.fairchildtv.com/news.php?n=5c2868adb73b Vancouver 23a26ca29b7244babfdb Oct 17 Kamloopscity.com Kamloops “Drivers urged to -

Getting a on Transmedia

® A PUBLICATION OF BRUNICO COMMUNICATIONS LTD. SPRING 2014 Getting a STATE OF SYN MAKES THE LEAP GRIon transmediaP + NEW RIVALRIES AT THE CSAs MUCH TURNS 30 | EXIT INTERVIEW: TOM PERLMUTTER | ACCT’S BIG BIRTHDAY PB.24462.CMPA.Ad.indd 1 2014-02-05 1:17 PM SPRING 2014 table of contents Behind-the-scenes on-set of Global’s new drama series Remedy with Dillon Casey shooting on location in Hamilton, ON (Photo: Jan Thijs) 8 Upfront 26 Unconventional and on the rise 34 Cultivating cult Brilliant biz ideas, Fort McMoney, Blue Changing media trends drive new rivalries How superfans build buzz and drive Ant’s Vanessa Case, and an exit interview at the 2014 CSAs international appeal for TV series with the NFB’s Tom Perlmutter 28 Indie and Indigenous 36 (Still) intimate & interactive 20 Transmedia: Bloody good business? Aboriginal-created content’s big year at A look back at MuchMusic’s three Canadian producers and mediacos are the Canadian Screen Awards decades of innovation building business strategies around multi- platform entertainment 30 Best picture, better box offi ce? 40 The ACCT celebrates its legacy Do the new CSA fi lm guidelines affect A tribute to the Academy of Canadian 24 Synful business marketing impact? Cinema and Television and 65 years of Going inside Smokebomb’s new Canadian screen achievements transmedia property State of Syn 32 The awards effect From books to music to TV and fi lm, 46 The Back Page a look at what cultural awards Got an idea for a transmedia project? mean for the business bottom line Arcana’s Sean Patrick O’Reilly charts a course for success Cover note: This issue’s cover features Smokebomb Entertainment’s State of Syn.