Finding Meaning and Value in Tel Aviv's Street

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sigma 04.04 Copy.Indd

Parsec April 2004 Meeting Date and Time: April 10th 2004, 2 PM (Although members tend to gather early.) Topic: Dan Bloch on “The History of Tall Build ings from the Pyramids to 2010.” Location: East Liberty Branch of Carnegie Library The Newsletter of PARSEC • April 2004 • Issue 217 (Directions on page 11.) SIGMA Tentative Meeting Schedule May 2004 Date: May 8th, 2004 Topic: TBA Location: East Liberty Branch of Carnegie Library June 2004 Date: June 12th, 2004 Topic: TBA Location: East Liberty Branch of Carnegie Library Cover Art by Diana Harlan Stein In This Issue: Kosak on Planetes PARSEC Pittsburgh Areaʼs Premiere Science-Fiction Organization Tjernlund on P.O. Box 3681, Pittsburgh, PA 15230-3681 Cassini/Huygens President - Kevin Geiselman Vice President - Kevin Hayes Irvine on Eragon Treasurer - Greg Armstrong Secretary - Bill Covert Commentator - Ann Cecil Website: trfn.clpgh.org/parsec Meetings - Second Saturday of every month. Dues: $10 full member, $2 Supporting member Sigma is edited by David Brody Send article submissions to: [email protected] View From the Outside The President’s Column - Kevin Geiselman Announcements Last month, I attended the Tekkoshocon anime con- vention. It was much like the previous year with plenty of DVDʼs and manga in the dealerʼs room, computer • PARSECʼs Mary Soon Lee will have the games, video rooms (“Full Metal Panic? Fumoffu” was story, “Shenʼs Daughter” in the Fantasy absolutely hysterical), panels, artists and cosplayers. I Best of 2003 collection, edited by David was there for a few hours before I realized something Hartwell and Kathryn Kramer was missing. It was me. Last year I went in my Klingon gear and fit right in. -

Pixaçāo: the Criminalization and Commodification of Subcultural Struggle in Urban Brazil

Kent Academic Repository Full text document (pdf) Citation for published version Gil Larruscahim, Paula (2018) Pixação: the criminalization and commodification of subcultural struggle in urban Brazil. Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) thesis, University of Kent,. DOI Link to record in KAR https://kar.kent.ac.uk/70308/ Document Version Publisher pdf Copyright & reuse Content in the Kent Academic Repository is made available for research purposes. Unless otherwise stated all content is protected by copyright and in the absence of an open licence (eg Creative Commons), permissions for further reuse of content should be sought from the publisher, author or other copyright holder. Versions of research The version in the Kent Academic Repository may differ from the final published version. Users are advised to check http://kar.kent.ac.uk for the status of the paper. Users should always cite the published version of record. Enquiries For any further enquiries regarding the licence status of this document, please contact: [email protected] If you believe this document infringes copyright then please contact the KAR admin team with the take-down information provided at http://kar.kent.ac.uk/contact.html PIXAÇĀO: THE CRIMINALIZATION AND COMMODIFICATION OF SUBCULTURAL STRUGGLE IN URBAN BRAZIL By Paula Gil Larruscahim Word Count: 83023 Date of Submission: 07 March 2018 Thesis submitted to the University of Kent and Utrecht University in partial fulfillment for requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy after following the Erasmus Mundus Doctoral Programme in Cultural and Global Criminology. University of Kent, School of Sociology, Social Policy and Social Research Utrecht University, Willem Pompe Institute for Criminal Law and Criminology 1 Statement of Supervision Acknowledgments This research was co-supervised by Prof. -

Trompe L'œil: an Approach to Promoting Art Tourism (Case Study: Shiraz City, Iran)

Trompe l’œil: an approach to promoting art tourism (case study: Shiraz city, Iran) Zahra Nikoo, Neda Torabi Farsani and Mohamadreza Emadi Abstract Zahra Nikoo, Purpose – Trompe l’oeil as a novel art technique can not only promote art tourism but can also transform Neda Torabi Farsani and the landscape of a city into a platform for negotiation. Furthermore, trompe l’oeil aims to create a joyful, Mohamadreza Emadi all entertaining, new experience and an interactive environment for tourists in the cities. This paper are based at the Art highlights the introduction of trompe l’oeil as a new tourist attraction in Shiraz (Iran). Moreover, the goals University of Isfahan, of this study are to explore the role of trompe l’oeil (three-dimensional [3D] street painting) in promoting Isfahan, Iran. art tourism, to investigate the tendency of tourists toward experiencing art tours and trompe l’oeil and to determine the priority of trompe l’oeil themes from the domestic tourists’ perspective. Design/methodology/approach – Qualitative and quantitative methods were used in this research study. Findings – On the basis of the results of this study, it can be concluded that domestic tourists are eager to experience art tours and trompe l’oeil attractions and activities, except for buying and wearing 3D- printed clothes. In addition, trompe l’oeil on street floors and walls with funny, joyful and cultural-artistic and national-historical themes is more attractive for them. Originality/value – No significant academic work has been undertaken in the field of art tourism to evaluate the attitude of tourists toward the trompe l’oeil attractions and activities. -

İncəsənət Və Mədəniyyət Problemləri Jurnalı

AZƏRBAYCAN MİLLİ ELMLƏR AKADEMİYASI AZERBAIJAN NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES НАЦИОНАЛЬНАЯ АКАДЕМИЯ НАУК АЗЕРБАЙДЖАНА MEMARLIQ VƏ İNCƏSƏNƏT İNSTİTUTU INSTITUTE OF ARCHITECTURE AND ART ИНСТИТУТ АРХИТЕКТУРЫ И ИСКУССТВА İncəsənət və mədəniyyət problemləri Beynəlxalq Elmi Jurnal N 4 (74) Problems of Arts and Culture International scientific journal Проблемы искусства и культуры Международный научный журнал Bakı - 2020 Baş redaktor: ƏRTEGİN SALAMZADƏ, AMEA-nın müxbir üzvü (Azərbaycan) Baş redaktorun müavini: GULNARA ABDRASİLOVA, memarlıq doktoru, professor (Qazaxıstan) Məsul katib : FƏRİDƏ QULİYEVA, sənətşünaslıq üzrə fəlsəfə doktoru (Azərbaycan) Redaksiya heyətinin üzvləri: ZEMFİRA SƏFƏROVA – AMEA-nın həqiqi üzvü (Azərbaycan) RƏNA MƏMMƏDOVA – AMEA-nın müxbir üzvü (Azərbaycan) RƏNA ABDULLAYEVA – sənətşünaslıq doktoru, professor (Azərbaycan) SEVİL FƏRHADOVA – sənətşünaslıq doktoru (Azərbaycan) RAYİHƏ ƏMƏNZADƏ - memarlıq doktoru, professor (Azərbaycan) VLADİMİR PETROV – fəlsəfə elmləri doktoru, professor (Rusiya) KAMOLA AKİLOVA – sənətşünaslıq doktoru, professor (Özbəkistan) MEYSER KAYA – fəlsəfə doktoru (Türkiyə) VİDADİ QAFAROV – sənətşünaslıq üzrə fəlsəfə doktoru, dosent (Azərbaycan) Editor-in-chief: ERTEGIN SALAMZADE, corresponding member of ANAS (Azerbaijan) Deputy editor: GULNARA ABDRASSILOVA, Prof., Dr. (Kazakhstan) Executive secretary: FERİDE GULİYEVA Ph.D. (Azerbaijan) Members to editorial board: ZEMFIRA SAFAROVA – academician of ANAS (Azerbaijan) RANA MAMMADOVA – corresponding-member of ANAS (Azerbaijan) RANA ABDULLAYEVA – Prof., Dr. (Azerbaijan) -

The Reinvigoration of Oakland Neighborhoods Through Public Art Installations

The Reinvigoration of Oakland Neighborhoods Through Public Art Installations Riley Anderson-Barrett California Polytechnic State University, San Luis Obispo College of Architecture and Environmental Design City and Regional Planning Department Senior Project June 2019 1 (Riggs) The Reinvigoration of Oakland Neighborhoods Through Public Art Installations Riley Anderson-Barrett Senior Project City and Regional Planning Department California Polytechnic State University - San Luis Obispo June 2019 © 2019 Riley Anderson-Barrett 2 Approval Page Title: The Reinvigoration of Oakland Neighborhoods Through Public Art Installations Author: Riley Anderson-Barrett, BSCRP student Date Submitted: June 14, 2019 Signature of parties: Student: Riley Anderson-Barrett date Advisor: Vicente del Rio, PhD date Department Head: Michael Boswell, PhD date 3 Table of Contents Chapter 1. Introduction 5 Chapter 2. The Role of Public Art in the City 7 Forms of Art 11 Public Art Installations 13 Chapter 3. Case Studies 16 Washington DC 18 Buenos Aires, Argentina 21 Paris, France 24 Lessons Learned 27 Chapter 4. The Case of Oakland 28 Background of Oakland 29 Project Proposal 32 Location 1 34 Location 2 45 Location 3 56 Implementation 67 Chapter 5. Conclusion 75 Chapter 6. References 78 4 Chapter 1. Introduction 5 (Illuminaries, 2013) The driving factor behind this project is my interest in how public art can drastically improve areas with somewhat little tangible change. With the implementation of a few key pieces, an area can gain recognition, triangulation, and life. Recognition begins when the location becomes recognizable and memorable, as opposed to being yet another mundane street corner or node. Making a location memorable and recognizable sparks the interest and desire for people to come visit the area. -

Spring 2021 Houston Seminar Brochure

THE HOUSTON SEMINAR SPRING 2021 As we continue to navigate challenges and new ways of living with COVID-19, the Houston Seminar is offering more courses on Zoom, as well as outdoor, socially distanced in-person experiences around Houston. Please join us as we dive into literature, landscape, history, philosophy, A Note politics, and more. Most of our Zoom courses will be recorded, and will be available on our website for two weeks after they take place. Please note To Our that by registering for Zoom courses, you are understood to be giving your THE HOUSTON SEMINAR Patrons permission to be recorded. Visit www.houstonseminar.org to learn more and to register for courses. The Houston Seminar was founded in 1977 for the purpose of stimulating learning and cultural awareness. Each spring and fall the nonprofit group offers lectures and study tours focused on varied topics that may include art, January architecture, literature, music, theater, history, politics, philosophy, psychology, SMTW TH FS religion, the natural environment, and current trends and events. Spring 2021 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 BOARD OF DIRECTORS ADVISORY BOARD Daytime Page 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 The Many Names of Slavery 7 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 Gail Adler Nancy Crow Allen 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 Bettie Cartwright Memorial Park: Vera Baker 9 31 Marcela Descalzi Brave Jan Cato Implementing the Ten-Year Plan February Kathleen Huggins Clarke Diane Cannon What’s with That Wall? Exploring 10 1 2 3 4 5 6 Sandy Godfrey Houston’s Street Art (tours) Barbara Catechis Kate Hawk 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Liz Crowell Nancy F. -

Reading the Fantastic Imagination

Reading the Fantastic Imagination Reading the Fantastic Imagination: The Avatars of a Literary Genre Edited by Dana Percec Reading the Fantastic Imagination: The Avatars of a Literary Genre Edited by Dana Percec This book first published 2014 Cambridge Scholars Publishing 12 Back Chapman Street, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2XX, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2014 by Dana Percec and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-5387-9, ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-5387-3 TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword ................................................................................................. viii Introduction .............................................................................................. xv It’s a Kind of Magic Dana Percec Part I: Fantasy: Terms and Boundaries Chapter One ................................................................................................ 2 Fantasy: Beyond Failing Definitions Pia Brînzeu Chapter Two ............................................................................................. 39 Gothic Literature: A Brief Outline Francisco Javier Sánchez-Verdejo Pérez Chapter Three .......................................................................................... -

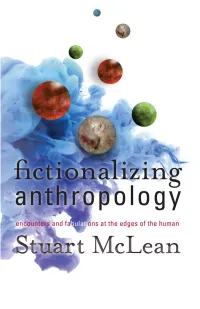

Fictionalizing Anthropology This Page Intentionally Left Blank Fictionalizing Anthropology

Fictionalizing Anthropology This page intentionally left blank Fictionalizing Anthropology Encounters and Fabulations at the Edges of the Human Stuart McLean University of Minnesota Press Minneapolis • London Permission to quote from Transfer Fat by Aase Berg, translated by Johannes Göransson (Ugly Duckling Presse, 2012), is granted by the publisher. Copyright 2017 by the Regents of the University of Minnesota All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Published by the University of Minnesota Press 111 Third Avenue South, Suite 290 Minneapolis, MN 55401- 2520 http://www.upress.umn.edu The University of Minnesota is an equal- opportunity educator and employer. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: McLean, Stuart, author. Title: Fictionalizing anthropology : encounters and fabulations at the edges of the human / Stuart McLean. Description: Minneapolis : University of Minnesota Press, [2017] | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2017005481 (print) | ISBN 978-1-5179-0271-1 (hc) | ISBN 978-1-5179-0272-8 (pb) Subjects: LCSH: Anthropology—Philosophy. | Ethnology—Philosophy. | Literature and anthropology. | Art and anthropology. Classification: LCC GN33 .M35 2017 (print) | DDC 301.01—dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017005481 Contents Prologue vii Part I. Anthropology: A Fabulatory Art 1 An Encounter in the Mist 3 2 Talabot 21 3 Fake 34 4 Anthropologies and Fictions 45 5 Knud Rasmussen 49 6 The Voice of the Thunder 67 7 Metaphor and/or Metamorphosis 73 8 “They Aren’t Symbols— They’re Real” 88 Part II. -

Towards a Cognitive Theory of (Canadian) Syncretic Fantasy By

University of Alberta The Word for World is Story: Towards a Cognitive Theory of (Canadian) Syncretic Fantasy by Gregory Bechtel A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English English and Film Studies ©Gregory Bechtel Fall 2011 Edmonton, Alberta Permission is hereby granted to the University of Alberta Libraries to reproduce single copies of this thesis and to lend or sell such copies for private, scholarly or scientific research purposes only. Where the thesis is converted to, or otherwise made available in digital form, the University of Alberta will advise potential users of the thesis of these terms. The author reserves all other publication and other rights in association with the copyright in the thesis and, except as herein before provided, neither the thesis nor any substantial portion thereof may be printed or otherwise reproduced in any material form whatsoever without the author's prior written permission. Abstract Unlike secondary world fantasy, such as that of J.R.R. Tolkien, what I call syncretic fantasy is typically set in a world that overlaps significantly with the contemporary "real" or cognitive majoritarian world in which we (i.e. most North Americans) profess to live our lives. In terms of popular publication, this subgenre has been recognized by fantasy publishers, readers, and critics since (at least) the mid 1980s, with Charles De Lint's bestselling Moonheart (1984) and subsequent "urban fantasies" standing as paradigmatic examples of the type. Where secondary world fantasy constructs its alternative worlds in relative isolation from conventional understandings of "reality," syncretic fantasy posits alternative realities that coexist, interpenetrate, and interact with the everyday real. -

Artists and Art Installations

alk chalk & pa dew inte Si d wall murals Art SEPTEMBER 4 - 12, 2021 Artists and Art Installations Returning Featured Mural Artist - David Mark Zimmerman (aka Bigshot Robot) Wall mural address: Ace Hardware, 200 S River St bigshot-robot.com Bigshot Robot is a Milwaukee-based designer with creations that explore curiosity, vibrancy, humor and movement. In his installations there is always a sense of imagination at play with colorful palettes full of energetic patterns. You can see some of his work around Milwaukee at places like Black Cat Alley, Bayshore, Commonplace / Tasha Rae, and Classic Slice. Bigshot participated in Art Infusion 2020 and completed the beloved Dog Bone Mural at the back of the building at 215 W Milwaukee St in Janesville. Most recently and on the heels of a Milwaukee Bucks NBA Finals win, Bigshot was commissioned to create a mural in the Walker’s Point neighborhood of a fierce buck that can be seen from various viewpoints in Milwaukee. Ivan Roque of Miami, Florida Wall mural address: Rock River Charter School, 31 W Milwaukee Street ivanroque.com Born December of 1991, Ivan J. Roque is a Cuban-American visual artist from Miami, Florida. Raised in the inner city of the infamous Carol City with a passion for the concepts of birth, death, renewal and social struggles, his influences range from the old masters to the new such as Caravaggio, Marc Rothko, Typoe and Gianni Versace. Roque has been able to accomplish many achievements for his young age, including working with rapper Denzel Curry, collaborating with major brands like Samsung, Becks, Seagram's Gin, Ultra Music Festival and showcasing alongside established artists such as The London Police, David Detuna, John "CRASH" Matos and many more. -

Ka-Boom Licence to Thrill on a Mission LIFTING the LID on VIDEO GAMES

ALL FORMATS LIFTING THE LID ON VIDEO GAMES Licence Ka-boom When games look to thrill like comic books Tiny studios making big licensed games On a mission The secrets of great campaign design Issue 33 £3 wfmag.cc Yacht Club’s armoured hero goes rogue 01_WF#33_Cover V3_RL_DH_VI_HK.indd 2 19/02/2020 16:45 JOIN THE PRO SQUAD! Free GB2560HSU¹ | GB2760HSU¹ | GB2760QSU² 24.5’’ 27’’ Sync Panel TN LED / 1920x1080¹, TN LED / 2560x1440² Response time 1 ms, 144Hz, FreeSync™ Features OverDrive, Black Tuner, Blue Light Reducer, Predefined and Custom Gaming Modes Inputs DVI-D², HDMI, DisplayPort, USB Audio speakers and headphone connector Height adjustment 13 cm Design edge-to-edge, height adjustable stand with PIVOT gmaster.iiyama.com Team Fortress 2: death by a thousand cuts? t may be 13 years old, but Team Fortress 2 is to stop it. Using the in-game reporting tool does still an exceptional game. A distinctive visual nothing. Reporting their Steam profiles does nothing. style with unique characters who are still Kicking them does nothing because another four will I quoted and memed about to this day, an join in their place. Even Valve’s own anti-cheat service open-ended system that lets players differentiate is useless, as it works on a delay to prevent the rapid themselves from others of the same class, well- JOE PARLOCK development of hacks that can circumvent it… at the designed maps, and a skill ceiling that feels sky-high… cost of the matches they ruin in the meantime. Joe Parlock is a even modern heavyweights like Overwatch and So for Valve to drop Team Fortress 2 when it is in freelance games Paladins struggle to stand up to Valve’s classic. -

Lies and Little Deaths: Stories

ABSTRACT LUNDBERG, JASON ERIK. Lies and Little Deaths: Stories. (Under the direction of Dr. John J. Kessel.) This collection of stories covers a wide variety of characters and settings, which alternate (for the most part) between third- and first-person viewpoints, with the final piece, “In Jurong,” told in second person. Most of the tales take place in the mundane world of the present day, but a world that allows the magical or surreal to seep through. This blending of the realistic world with the fantastic one is of great importance to me as a writer and as a reader, as is the discussion of its merits within the broader field of literature. These twenty-three stories explore the perils and pleasures of sex (mostly the perils), the issues of the day but twisted into satire or literalized metaphor, the slightly magical, the truly bizarre, and the constant questioning of identity and the afterlife. LIES AND LITTLE DEATHS: STORIES by JASON ERIK LUNDBERG A thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty of North Carolina State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts ENGLISH Raleigh 2005 APPROVED BY: _______________________________ _______________________________ Wilton Barnhardt Jon Thompson _______________________________ John J. Kessel Chair of Advisory Committee DEDICATION for Janet ii BIOGRAPHY Jason Erik Lundberg once read all of Stephen King’s The Girl Who Loved Tom Gordon and got shot at in the same afternoon. He was born in Brooklyn, but has called North Carolina home for the past seventeen years. His fiction and non-fiction have appeared in such places as Strange Horizons, Fantastic Metropolis, Infinity Plus, The Green Man Review, Fishnet, Intracities, Americana, Lone Star Stories, Electric Velocipede and the Serbian fiction magazine Znak Sagite.