Clear and Present Thinking Project Director Brendan Myers (Cegep Heritage College)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The U.F.A. Who Is Interested in the States Power Trust

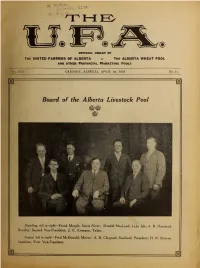

M. WcRae, ... pederal, Alta. OFFICIAL ORGAN OF THE UNITED FARMERS OF ALBERTA THE ALBERTA WHEAT POOL AND OTHER PROVINCIAL MARKETING POOLS Vol. VIII. CALGARY, ALBERTA, APRIL 1st, 1929 No. 11. m Board of the Alberta Livestock Pool Standing, left to r/gA/—Frank Marple. Spirit River; Donald MacLeod, Lake Isle; A. B. Haarstad, Bentley. Second Vice-President; J. E, Evenson, Taber. Seated, left to right—Fred McDonald. Mirror; A. B. Claypool, Swalwell. President; H. N. Stearns. Innisfree, First Vice-President. 2 rsw) THE U. F. A. April iBt, lyz^i Ct The Weed-Killing CULTIVATOR with the exclusive Features The Climax Cultivator leads the war on weeds that trob these Provinces of $60,000,000 every year. Put it to work for you! Get the extra profits it is ready to make for you—clean grain, more grain, more money. The Climax has special featxires found in no Sold in Western Canada by other cultivator. Hundreds of owners acclaim it Cockshutt Plow Co., as a durable, dependable modem machine. Limited The Climax is made to suit every type of farm Winnipeg, Regina, and any kind of power. great variety of equip- Saskatoon, Calgary, A Edmonton ment for horses or tractors. Special Features of the Climax Manufactured by The Patented Depth Regulator saves The Frost & Wood Co., Limited pow«r and horse fag. The Power Lift saves time. Points working independ- Smiths Falls, Oat. ently do better work. Heavy Duty Drag Bars equipped with powerful coils prings prevent breakage. Rigid Angle Steel Frame. Variety of points from 2" to 14". llVi" points are standard eqvdpment. -

Towards a Disinformation Resilient Society? the Experience of the Czech Republic

Cosmopolitan ARTICLE (PEER-REVIEWED) Civil Societies: an Towards a Disinformation Resilient Society? Interdisciplinary Journal The Experience of the Czech Republic Vol. 11, No. 1 Ondřej Filipec 2019 Department of Politics and Social Sciences, Palacký University Olomouc, Křížkovského 511/8, 771 47 Olomouc, Czechia. ondrejfi[email protected] DOI: https://doi.org/10.5130/ccs.v11.i1.6065 Article History: Received05/09/2018; Revised 05/02/19; Accepted 14/02/19; Published 28/03/2019 Abstract © 2019 by the author(s). This is an Open Access article Disinformation is currently an important threat to modern democratic societies and has distributed under the terms a critical impact on the quality of public life. Tis article presents an organic approach to of the Creative Commons understanding of the issue of disinformation that is derived from the context of the Czech Attribution 4.0 International Republic. Te approach builds on the various similarities with virology where disinformation (CC BY 4.0) License (https:// creativecommons.org/licenses/ is compared to a hostile virus that is spread in a certain environment and may penetrate the by/4.0/), allowing third parties human body. Contribution is providing Czech experience in eight areas related to creation and to copy and redistribute the spread of disinformation and analyzing obstacles for building disinformation resilience. material in any medium or format and to remix, transform, and build upon the Keywords material for any purpose, even Disinformation, Propaganda, Fake News, Information Warfare, Hybrid Warfare, Resilience, commercially, provided the Czech Republic original work is properly cited and states its license. Citation: Filipec, O. 2019. -

Bharati Volume 4

SARASVATI Bharati Volume 4 Gold bead; Early Dynastic necklace from the Royal Cemetery; now in the Leeds collection y #/me raed?sI %/-e A/hm! #N/m! Atu?vm! , iv/Èaim?Sy r]it/ e/dm! -ar?t jn?m! . (Vis'va_mitra Ga_thina) RV 3.053.12 I have made Indra glorified by these two, heaven and earth, and this prayer of Vis'va_mitra protects the race of Bharata. [Made Indra glorified: indram atus.t.avam-- the verb is the third preterite of the casual, I have caused to be praised; it may mean: I praise Indra, abiding between heaven and earth, i.e. in va_kdevi Sarasvati the firmament]. Dr. S. Kalyanaraman Babasaheb (Umakanta Keshav) Apte Smarak Samiti Bangalore 2003 PDF Created with deskPDF PDF Writer - Trial :: http://www.docudesk.com SARASVATI: Bharati by S. Kalyanaraman Copyright Dr. S. Kalyanaraman Publisher: Baba Saheb (Umakanta Keshav) Apte Smarak Samiti, Bangalore Price: (India) Rs. 500 ; (Other countries) US $50 . Copies can be obtained from: S. Kalyanaraman, 3 Temple Avenue, Srinagar Colony, Chennai, Tamilnadu 600015, India email: [email protected] Tel. + 91 44 22350557; Fax 24996380 Baba Saheb (Umakanta Keshav) Apte Smarak Samiti, Yadava Smriti, 55 First Main Road, Seshadripuram, Bangalore 560020, India Tel. + 91 80 6655238 Bharatiya Itihasa Sankalana Samiti, Annapurna, 528 C Saniwar Peth, Pune 411030 Tel. +91 020 4490939 Library of Congress cataloguing in publication data Kalyanaraman, Srinivasan. Sarasvati/ S. Kalyanaraman Includes bibliographical references and index 1.River Sarasvati. 2. Indian Civilization. 3. R.gveda Printed in India at K. Joshi and Co., 1745/2 Sadashivpeth, Near Bikardas Maruti Temple, Pune 411030, Bharat ISBN 81-901126-4-0 FIRST PUBLISHED: 2003 2 PDF Created with deskPDF PDF Writer - Trial :: http://www.docudesk.com About the Author Dr. -

Philosophy Sunday, July 8, 2018 12:01 PM

Philosophy Sunday, July 8, 2018 12:01 PM Western Pre-Socratics Fanon Heraclitus- Greek 535-475 Bayle Panta rhei Marshall Mcluhan • "Everything flows" Roman Jakobson • "No man ever steps in the same river twice" Saussure • Doctrine of flux Butler Logos Harris • "Reason" or "Argument" • "All entities come to be in accordance with the Logos" Dike eris • "Strife is justice" • Oppositional process of dissolving and generating known as strife "The Obscure" and "The Weeping Philosopher" "The path up and down are one and the same" • Theory about unity of opposites • Bow and lyre Native of Ephesus "Follow the common" "Character is fate" "Lighting steers the universe" Neitzshce said he was "eternally right" for "declaring that Being was an empty illusion" and embracing "becoming" Subject of Heideggar and Eugen Fink's lecture Fire was the origin of everything Influenced the Stoics Protagoras- Greek 490-420 BCE Most influential of the Sophists • Derided by Plato and Socrates for being mere rhetoricians "Man is the measure of all things" • Found many things to be unknowable • What is true for one person is not for another Could "make the worse case better" • Focused on persuasiveness of an argument Names a Socratic dialogue about whether virtue can be taught Pythagoras of Samos- Greek 570-495 BCE Metempsychosis • "Transmigration of souls" • Every soul is immortal and upon death enters a new body Pythagorean Theorem Pythagorean Tuning • System of musical tuning where frequency rations are on intervals based on ration 3:2 • "Pure" perfect fifth • Inspired -

The Paradox of Tolerance

Religious privilege, tolerance and discrimination (part 2) – The paradox of tolerance What are religious privilege, tolerance and discrimination? Why do people support or oppose secularism? Q1. Should religious tolerance be limited? The paradox of tolerance The so-called “paradox of tolerance”, was first described by a philosopher called Karl Popper in his 1945 book: The Open Society and Its Enemies Vol. 1: “Less well known is the paradox of tolerance: Unlimited tolerance must lead to the disappearance of tolerance. If we extend unlimited tolerance even to those who are intolerant, if we are not prepared to defend a tolerant society against the onslaught of the intolerant, then the tolerant will be destroyed, and tolerance with them. — In this formulation, I do not imply, for instance, that we should always suppress the utterance of intolerant philosophies; as long as we can counter them by rational argument and keep them in check by public opinion, suppression would certainly be unwise. But we should claim the right to suppress them if necessary even by force; for it may easily turn out that they are not prepared to meet us on the level of rational argument, but begin by denouncing all argument; they may forbid their followers to listen to rational argument, because it is deceptive, and teach them to answer arguments by the use of their fists or pistols. We should therefore claim, in the name of tolerance, the right not to tolerate the intolerant.” Popper is not saying that we should abandon tolerance or have no tolerance for intolerance. But that in the interest of preserving overall tolerance we might have to limit tolerance in specific instances. -

The Rhetorical Function of Law for the Boundaries of Tolerance by João Maurício Adeodato

The Rhetorical Function of Law for the Boundaries of Tolerance by João Maurício Adeodato The Rhetorical Function of Law for the Boundaries of Tolerance by João Maurício Adeodato English Abstract Thinking of the discussions about the legal effects of the Brazilian Amnesty Law, the thesis in this paper is that positive law has to coercively assure the basic environment for the development of tolerance. So it has to stay completely apart from religion, politics, money etc., and it cannot privilege any sort of moral view, which would be in itself valid. The price to pay is the formalization, that is: the task of law is to guarantee an arena, a public space of procedural rules in which the different ideologies towards how the world ought to be can confront each other to gain the minds and opinions of the people. On the way to the thesis, I will first show how the sophistical movement turned into a rhetorical philosophy through the incorporation of the ideas of historicism, humanism and skepticism. In the second place, there will come an historical analysis of the idea of tolerance, nearly as old as culture itself. Then, in the same line, I will try to show more specifically how this evolution led to modern rhetoric, in order to, finally, situate the paradox of tolerance and how law could be able to deal with it and overcome the ethical burden that the modern democratic world has brought to it. Resumen en español En el contexto de las discusiones acerca de la Ley de la Amnistía a los crímenes políticos, cuyos efectos están en discusión en Brasil, la tesis en este texto es que el derecho positivo necesita asegurar coercitivamente el ambiente para el desarrollo de la tolerancia. -

Issues in the Normativity of Logic and the Logic As Model View By

Issues in the Normativity of Logic and the Logic as Model View by Haggeo Cadenas A Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts Approved November 2017 by the Graduate Supervisory Committee Angel Pinillos, Chair Bernard Kobes Shyam Nair Richard Creath ARIZONA STATE UNIVERSITY December 2017 ABSTRACT After surveying the literature on the normativity of logic, the paper answers that logic is normative for reasoning and rationality. The paper then goes on to discuss whether this constitutes a new problem in issues in normativity, and the paper affirms that it does. Finally, the paper concludes by explaining that the logic as model view can address this new problem. i TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION………………………………………………………………………...1 A ROMP THROUGH THE NORMATIVITY OF LOGIC: HARMAN AND THE NORMATIVITY OF LOGIC ……………...……………………………………………..6 Can Harman-esque Worries Lead to Normative Skepticism? ..............................17 Is Logic Normative?..............................................................................................19 WHY THINK THERE IS A UNIQUE PROBLEM?.......................................................22 Field’s account of the Normativity of Logic………………..…………………..35 Field and the Instrumental Conception of Epistemic Rationality………………..38 THE LOGIC AS MODEL VIEW AND NORMATIVITY……………………………...47 Three Ways Logic Might Relate to Reasoning……………………….………….47 An Elaboration of the Logic as Model View…………………………………….50 The Logic as Model View: A Layout, Application, and Analysis………….……55 A Layout………………………………………………………………………....55 The Application and Analysis……………………………………………………58 CONCLUSION…………………………………………………………………………..62 BIBLIOGRAPHY………………………………………………………………………..64 ii Issues in the Normativity of Logic and the Logic as Model View §1: Introduction What was the charge that Plato and Socrates levied against to sophists? Simply put, it’s that they, “made the weaker argument appear the stronger?” Surprisingly, this charge was brought against Socrates in his trial. -

Paradoxes Situations That Seems to Defy Intuition

Paradoxes Situations that seems to defy intuition PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Tue, 08 Jul 2014 07:26:17 UTC Contents Articles Introduction 1 Paradox 1 List of paradoxes 4 Paradoxical laughter 16 Decision theory 17 Abilene paradox 17 Chainstore paradox 19 Exchange paradox 22 Kavka's toxin puzzle 34 Necktie paradox 36 Economy 38 Allais paradox 38 Arrow's impossibility theorem 41 Bertrand paradox 52 Demographic-economic paradox 53 Dollar auction 56 Downs–Thomson paradox 57 Easterlin paradox 58 Ellsberg paradox 59 Green paradox 62 Icarus paradox 65 Jevons paradox 65 Leontief paradox 70 Lucas paradox 71 Metzler paradox 72 Paradox of thrift 73 Paradox of value 77 Productivity paradox 80 St. Petersburg paradox 85 Logic 92 All horses are the same color 92 Barbershop paradox 93 Carroll's paradox 96 Crocodile Dilemma 97 Drinker paradox 98 Infinite regress 101 Lottery paradox 102 Paradoxes of material implication 104 Raven paradox 107 Unexpected hanging paradox 119 What the Tortoise Said to Achilles 123 Mathematics 127 Accuracy paradox 127 Apportionment paradox 129 Banach–Tarski paradox 131 Berkson's paradox 139 Bertrand's box paradox 141 Bertrand paradox 146 Birthday problem 149 Borel–Kolmogorov paradox 163 Boy or Girl paradox 166 Burali-Forti paradox 172 Cantor's paradox 173 Coastline paradox 174 Cramer's paradox 178 Elevator paradox 179 False positive paradox 181 Gabriel's Horn 184 Galileo's paradox 187 Gambler's fallacy 188 Gödel's incompleteness theorems -

Logic in the Light of Cognitive Science

STUDIES IN LOGIC, GRAMMAR AND RHETORIC 48 (61) 2016 DOI: 10.1515/slgr-2016-0057 Jan Woleński University of Information, Technology and Management Rzeszow LOGIC IN THE LIGHT OF COGNITIVE SCIENCE Abstract. Logical theory codifies rules of correct inferences. On the other hand, logical reasoning is typically considered as one of the most fundamental cognitive activities. Thus, cognitive science is a natural meeting-point for investigations about the place of logic in human cognition. Investigations in this perspec- tive strongly depend on a possible understanding of logic. This paper focuses on logic in the strict sense; that is, the theory of deductive inferences. Two problems are taken into account, namely: (a) do humans apply logical rules in ordinary reasoning?; (b) the genesis of logic. The second issue is analyzed from the naturalistic point of view. Keywords: logica docens, logica utens, rules of inference, genetic code, natural- ism, information. Logic is traditionally considered as very closely associated with cogni- tive activities. Philosophers and psychologists frequently say that human rationality consists in using logical tools in thinking and other cognitive ac- tivities, e.g. making decisions. In particular, reasoning and its correctness seem to have their roots in a faculty, which, by way of analogy with the lan- guage faculty, could be viewed as logical competence. On the other hand, one might also argue, logical competence itself is a manifestation of logic. Independently, whether logic is prior to logical competence or whether the latter has its grounds in the former, the concept of logic is indispensable for any analysis of the practice of inferences performed by humans as well as perhaps other species.1 The above, a very sketchy introduction, justifies taking the concept of logic as fundamental for my further analysis of logical aspects related to the cognitive space. -

PAGANISM a Brief Overview of the History of Paganism the Term Pagan Comes from the Latin Paganus Which Refers to Those Who Lived in the Country

PAGANISM A brief overview of the history of Paganism The term Pagan comes from the Latin paganus which refers to those who lived in the country. When Christianity began to grow in the Roman Empire, it did so at first primarily in the cities. The people who lived in the country and who continued to believe in “the old ways” came to be known as pagans. Pagans have been broadly defined as anyone involved in any religious act, practice, or ceremony which is not Christian. Jews and Muslims also use the term to refer to anyone outside their religion. Some define paganism as a religion outside of Christianity, Judaism, Hinduism, Islam, and Buddhism; others simply define it as being without a religion. Paganism, however, often is not identified as a traditional religion per se because it does not have any official doctrine; however, it has some common characteristics within its variety of traditions. One of the common beliefs is the divine presence in nature and the reverence for the natural order in life. In the strictest sense, paganism refers to the authentic religions of ancient Greece and Rome and the surrounding areas. The pagans usually had a polytheistic belief in many gods but only one, which represents the chief god and supreme godhead, is chosen to worship. The Renaissance of the 1500s reintroduced the ancient Greek concepts of Paganism. Pagan symbols and traditions entered European art, music, literature, and ethics. The Reformation of the 1600s, however, put a temporary halt to Pagan thinking. Greek and Roman classics, with their focus on Paganism, were accepted again during the Enlightenment of the 1700s. -

The Business of Life and Death, Vol. 1: Values and Economies

The Business of Life and Death, Vol. 1: Values and Economies Collected Philosophical Essays by Giorgio Baruchello, PhD Gatineau, Quebec Canada Published by Northwest Passage Books, 2018. Complete Table of Contents Part I - Introductions The Cancer Stage of Capitalism Value Wars From Crisis to Cure Part II - Applications What Is To Be Conserved? An Appraisal of Political Conservatism Good And Bad Tourism Paul Krugman’s Banking Metastases Social Philosophy and Oncology On the Mission of Public Universities Part III - Implications Adam Smith, Historical and Rhetorical Cornelius Castoriadis and the Crux of Adam Smith’s Liberty The Price of Tranquility: Cruelty and Death in Adam Smith’s Liberalism Adam Smith Can Never Be Wrong Five Books of Economic History A History of Economics Epilogue: Good and Bad Capitalism This Sample Includes: Introduction 2 What Is To Be Conserved? An Appraisal of Political Conservatism 9 Copyright © 2018 by Giorgio Baruchello. All rights reserved. This sample of the text may be shared freely provided it is not modified in any way, not used for the reader’s commercial purposes, and that the author’s name remains attached to the work. 1 Baruchello / The Business of Life and Death, vol 1: Values and Economies The Business of Life and Death, Vol. 1: Values and Economies Introduction A direct descendant of the Ontario Agricultural College, the University of Guelph can boast among the members of its vast academic family two great Canadian intellectuals, who have never been afraid of tackling public affairs and economic matters with unswerving courage, subtle acumen and dazzling style. The first one is John Kenneth—“Ken”—Galbraith (1908–2006). -

Introduction

i i OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, //, SPi i i PART I Introduction i i i i i i OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, //, SPi i i i i i i i i OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, //, SPi i i Logical Consequence Its Nature, Structure, and Application Colin R. Caret and Ole T. Hjortland . Introduction Recent work in philosophical logic has taken interesting and unexpected turns. It has seen not only a proliferation of logical systems, but new applications of a wide range of different formal theories to philosophical questions. As a result, philosophers have been forced to revisit the nature and foundation of core logical concepts, chief amongst which is the concept of logical consequence. This volume collects together some of the most important recent scholarship in the area by drawing on a wealth of contributions that were made over the lifetime of the AHRC-funded Foundations of Logical Consequence project. In the following introductory essay we set these contributions in context and identify how they advance important debates within the philosophy of logic. Logical consequence is the relation that obtains between premises and conclu- sion(s) in a valid argument. Validity, most will agree, is a virtue of an argument, butwhatsortofvirtue?Orthodoxyhasitthatanargumentisvalidifitmustbethe case that when the premises are true, the conclusion is true. Alternatively, that it is impossible for the premises to be true and the conclusion false simultaneously. In short, the argument is necessarily truth preserving. These platitudes, however, leave us with a number