Poverty, Wealth and Place in Britain, 1968-2005

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Across the Divide: Tackling Digital Exclusion in Glasgow

Across the Divide Tackling Digital Exclusion in Glasgow Douglas White The Carnegie UK Trust is an independent, endowed charitable trust incorporated by Royal Charter. We seek to improve the lives and wellbeing of people throughout the UK and Republic of Ireland by influencing public policy and demonstrating innovative practice. This project was made possible thanks to the and Jeremy Mitchell formerly at the work, help and support of many different people: Communications Consumer Panel; Trisha • Mark Diffley and Vanessa Chan of Ipsos McAuley and Annie McGovern at Consumer MORI carried out both the primary and Focus Scotland; Sarah Beattie-Smith at secondary research on which this report Citizens Advice Scotland; Laura Alexander at is based. They offered great imagination the Ofcom Advisory Committee for Scotland; and diligence to help us devise the right Laura Muir at Robert Gordon University; approach for the research, and applied their Vicki Hanson at University of Dundee; John considerable expertise and commitment to Crawford, Trustee at CILIP; Stuart Gibson at make this a successful study. Farrpoint; and Gillian Anderson at University of Strathclyde. • A number of people offered expert insight and improvement at various stages of the • Martyn Evans and Jennifer Wallace provided project, including the research design and valuable internal review and support. final report. These include Vicki Nash and • 200 citizens in Glasgow generously gave Claire Mack at Ofcom Scotland; Evelyn up their time to share with us their personal McDowall at Glasgow Housing Association; experiences and views on the internet, David Coyne and Lynsey Telford at Glasgow including why they go online and why City Council; Andrew Unsworth at Scottish they do not. -

First Drumchapel

First Drumchapel - Govan 3 via Partick, City Centre & Silverburn Monday to Friday (Summer) Ref.No.: T14 Service No 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 Drumchapel Station 0445 0515 0545 0608 0623 0633 0654 0710 0720 0731 0740 0750 0802 0814 0827 0839 0851 0903 0915 0927 0939 0951 1003 1015 Drumchapel Shopping Centre 0454 0524 0555 0618 0633 0643 0704 0721 0731 0742 0751 0801 0813 0825 0838 0850 0902 0914 0926 0938 0950 1002 1014 1026 Scotstoun 0508 0538 0610 0634 0649 0700 0721 0739 0749 0801 0811 0821 0833 0845 0857 0908 0920 0932 0944 0956 1008 1020 1032 1044 Partick, Merkland Street 0517 0547 0619 0644 0659 0710 0732 0751 0802 0814 0824 0834 0846 0858 0909 0920 0932 0944 0956 1008 1020 1032 1044 1056 Charing Cross 0527 0557 0629 0654 0709 0720 0743 0803 0815 0827 0836 0846 0858 0910 0921 0932 0944 0956 1008 1020 1032 1044 1056 1108 Union St, Central Station 0535 0605 0637 0650 0703 0718 0729 0741 0753 0804 0815 0827 0839 0848 0858 0910 0922 0933 0944 0956 1008 1020 1032 1044 1056 1108 1120 Eglinton Toll South 0541 0611 0643 0656 0709 0724 0735 0748 0800 0811 0822 0834 0846 0855 0905 0917 0929 0940 0951 1003 1015 1027 1039 1051 1103 1115 1127 Shawlands Cross 0548 0618 0650 0703 0716 0731 0742 0755 0807 0818 0830 0842 0854 0903 0913 0925 0937 0948 0959 1011 1023 1035 1047 1059 1111 1123 1135 Riverford Road, Morrisons 0553 0623 0655 0708 0721 0736 0747 0800 0812 0824 0836 0848 0900 0909 0919 0931 0943 0954 1005 1017 1029 1041 1053 1105 1117 1129 1141 Silverburn, Bus Stn 0933 0945 0955 1008 1019 1027 1043 1055 1107 1119 -

1 Minutes of the Meeting of Blairdardie and Old Drumchapel Community Council Held in the Blairdrum Neighbourhood Centre, 11 Keal

Minutes of the Meeting of Blairdardie and Old Drumchapel Community Council Held in the Blairdrum Neighbourhood Centre, 11 Keal Place, Blairdardie at 7pm on Monday 18th January 2016 1. Apologies for Absence: Bill Kidd MSP, Anne Mc Taggart MSP. Jonathon Findlay, Paul Carey, Glasgow City Councillors. Community Councillor: Mrs J. McCann. Mrs N Cunningham. 2. Minutes of Meeting Held on Monday 16th November 2015 Proposed: Mrs M.A.Morrison Seconded: Mrs G. Riddell 3. Matters Arising not on the Agenda: None. 4. Police Report: Blairdardie/Old Drumchapel “AE” Subdivision. Inspector –Drumchapel and West Police 532 3655 The Drumchapel Office 220 Drumry Road East G158PT is manned 24hours contact 0141 532 3600 or 532 3655. For “non” emergencies call 101 rather than “999”. Community police Constable Gordon McLaren. Gordon is part of the community team at Drumchapel Police Office and anticipated attending our future meetings. He reported that a few instances of “sneak in thefts” had occurred locally. Front doors had been left open and access had been gained to steal money or jewellery. A lot of thefts of vehicles have occurred where car keys were stolen from the house. Sometimes by “fishing via a hook” through a letter box. Also thefts from unlocked motor vehicles. Number plates have been stolen and the stolen plates put on another vehicle and the vehicle filled with fuel and then driven out of the filling station forecourt without paying. Call police if your number plate has been stolen. Question: Cars going on fire at community business in Dalsetter Avenue. Answer: Premises have put in extra security and police are aware of this and giving the premises extra attention. -

Glasgow City Community Health Partnership Service Directory 2014 Content Page

Glasgow City Community Health Partnership Service Directory 2014 Content Page About the CHP 1 Glasgow City CHP Headquarters 2 North East Sector 3 North West Sector 4 South Sector 5 Adult Protection 6 Child Protection 6 Emergency and Out-of-Hours care 6 Addictions 7 - 9 Asylum Seekers 9 Breast Screening 9 Breastfeeding 9 Carers 10 - 12 Children and Families 13 - 14 Dental and Oral Health 15 Diabetes 16 Dietetics 17 Domestic Abuse / Violence 18 Employability 19 - 20 Equality 20 Healthy Living 21 Health Centres 22 - 23 Hospitals 24 - 25 Housing and Homelessness 26 - 27 Learning Disabilities 28 - 29 Mental Health 30 - 40 Money Advice 41 Nursing 41 Physiotherapy 42 Podiatry 42 Respiratory 42 Rehabilitation Services 43 Sexual Health 44 Rape and Sexual Assault 45 Stop Smoking 45 Transport 46 Volunteering 46 Young People 47-49 Public Partnership Forum 50 Comments and Complaints 51-21 About Glasgow City Community Health Partnership Glasgow City Community Health Partnership (GCCHP) was established in November 2010 and provides a wide range of community based health services delivered in homes, health centres, clinics and schools. These include health visiting, health improvement, district nursing, speech and language therapy, physiotherapy, podiatry, nutrition and dietetic services, mental health, addictions and learning disability services. As well as this, we host a range of specialist services including: Specialist Children’s Services, Homeless Services and The Sandyford. We are part of NHS Greater Glasgow & Clyde and provide services for 584,000 people - the entire population living within the area defined by the LocalAuthority boundary of Glasgow City Council. Within our boundary, we have: 154 GP practices 136 dental practices 186 pharmacies 85 optometry practices (opticians) The CHP has more than 3,000 staff working for it and is split into three sectors which are aligned to local social work and community planning boundaries. -

National Retailers.Xlsx

THE NATIONAL / SUNDAY NATIONAL RETAILERS Store Name Address Line 1 Address Line 2 Address Line 3 Post Code M&S ABERDEEN E51 2-28 ST. NICHOLAS STREET ABERDEEN AB10 1BU WHS ST NICHOLAS E48 UNIT E5, ST. NICHOLAS CENTRE ABERDEEN AB10 1HW SAINSBURYS E55 UNIT 1 ST NICHOLAS CEN SHOPPING CENTRE ABERDEEN AB10 1HW RSMCCOLL130UNIONE53 130 UNION STREET ABERDEEN, GRAMPIAN AB10 1JJ COOP 204UNION E54 204 UNION STREET X ABERDEEN AB10 1QS SAINSBURY CONV E54 SOFA WORKSHOP 206 UNION STREET ABERDEEN AB10 1QS SAINSBURY ALF PL E54 492-494 UNION STREET ABERDEEN AB10 1TJ TESCO DYCE EXP E44 35 VICTORIA STREET ABERDEEN AB10 1UU TESCO HOLBURN ST E54 207 HOLBURN STREET ABERDEEN AB10 6BL THISTLE NEWS E54 32 HOLBURN STREET ABERDEEN AB10 6BT J&C LYNCH E54 66 BROOMHILL ROAD ABERDEEN AB10 6HT COOP GT WEST RD E46 485 GREAT WESTERN ROAD X ABERDEEN AB10 6NN TESCO GT WEST RD E46 571 GREAT WESTERN ROAD ABERDEEN AB10 6PA CJ LANG ST SWITIN E53 43 ST. SWITHIN STREET ABERDEEN AB10 6XL GARTHDEE STORE 19-25 RAMSAY CRESCENT GARTHDEE ABERDEEN AB10 7BL SAINSBURY PFS E55 GARTHDEE ROAD BRIDGE OF DEE ABERDEEN AB10 7QA ASDA BRIDGE OF DEE E55 GARTHDEE ROAD BRIDGE OF DEE ABERDEEN AB10 7QA SAINSBURY G/DEE E55 GARTHDEE ROAD BRIDGE OF DEE ABERDEEN AB10 7QA COSTCUTTER 37 UNION STREET ABERDEEN AB11 5BN RS MCCOLL 17UNION E53 17 UNION STREET ABERDEEN AB11 5BU ASDA ABERDEEN BEACH E55 UNIT 11 BEACH BOULEVARD RETAIL PARK LINKS ROAD, ABERDEEN AB11 5EJ M & S UNION SQUARE E51 UNION SQUARE 2&3 SOUTH TERRACE ABERDEEN AB11 5PF SUNNYS E55 36-40 MARKET STREET ABERDEEN AB11 5PL TESCO UNION ST E54 499-501 -

Open Space Strategy Consultative Draft

GLASGOW OPEN SPACE STRATEGY CONSULTATIVE DRAFT Prepared For: GLASGOW CITY COUNCIL Issue No 49365601 /05 49365601 /05 49365601 /05 Contents 1. Executive Summary 1 2. Glasgu: The Dear Green Place 11 3. What should open space be used for? 13 4. What is the current open space resource? 23 5. Place Setting for improved economic and community vitality 35 6. Health and wellbeing 59 7. Creating connections 73 8. Ecological Quality 83 9. Enhancing natural processes and generating resources 93 10. Micro‐Climate Control 119 11. Moving towards delivery 123 Strategic Environmental Assessment Interim Environment Report 131 Appendix 144 49365601 /05 49365601 /05 1. Executive Summary The City of Glasgow has a long tradition in the pursuit of a high quality built environment and public realm, continuing to the present day. This strategy represents the next steps in this tradition by setting out how open space should be planned, created, enhanced and managed in order to meet the priorities for Glasgow for the 21st century. This is not just an open space strategy. It is a cross‐cutting vision for delivering a high quality environment that supports economic vitality, improves the health of Glasgow’s residents, provides opportunities for low carbon movement, builds resilience to climate change, supports ecological networks and encourages community cohesion. This is because, when planned well, open space can provide multiple functions that deliver numerous social, economic and environmental benefits. Realising these benefits should be undertaken in a way that is tailored to the needs of the City. As such, this strategy examines the priorities Glasgow has set out and identifies six cross‐cutting strategic priority themes for how open space can contribute to meeting them. -

Glasgow City Health and Social Care Partnership Health Contacts

Glasgow City Health and Social Care Partnership Health Contacts January 2017 Contents Glasgow City Community Health and Care Centre page 1 North East Locality 2 North West Locality 3 South Locality 4 Adult Protection 5 Child Protection 5 Emergency and Out-of-Hours care 5 Addictions 6 Asylum Seekers 9 Breast Screening 9 Breastfeeding 9 Carers 10 Children and Families 12 Continence Services 15 Dental and Oral Health 16 Dementia 18 Diabetes 19 Dietetics 20 Domestic Abuse 21 Employability 22 Equality 23 Health Improvement 23 Health Centres 25 Hospitals 29 Housing and Homelessness 33 Learning Disabilities 36 Maternity - Family Nurse Partnership 38 Mental Health 39 Psychotherapy 47 NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde Psychological Trauma Service 47 Money Advice 49 Nursing 50 Older People 52 Occupational Therapy 52 Physiotherapy 53 Podiatry 54 Rehabilitation Services 54 Respiratory Team 55 Sexual Health 56 Rape and Sexual Assault 56 Stop Smoking 57 Volunteering 57 Young People 58 Public Partnership Forum 60 Comments and Complaints 61 Glasgow City Community Health & Care Partnership Glasgow Health and Social Care Partnership (GCHSCP), Commonwealth House, 32 Albion St, Glasgow G1 1LH. Tel: 0141 287 0499 The Management Team Chief Officer David Williams Chief Officer Finances and Resources Sharon Wearing Chief Officer Planning & Strategy & Chief Social Work Officer Susanne Miller Chief Officer Operations Alex MacKenzie Clincial Director Dr Richard Groden Nurse Director Mari Brannigan Lead Associate Medical Director (Mental Health Services) Dr Michael Smith -

Campus Travel Guide Final 08092016 PRINT READY

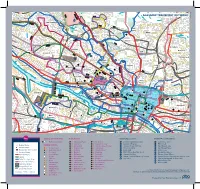

Lochfauld V Farm ersion 1.1 27 Forth and 44 Switchback Road Maryhill F C Road 6 Clyde Canal Road Balmore 1 0 GLASGOW TRANSPORT NETWORK 5 , 6 F 61 Acre0 A d Old Blairdardie oa R Drumchapel Summerston ch lo 20 til 23 High Knightswood B irkin e K F 6 a /6A r s de F 15 n R F 8 o Netherton a High d 39 43 Dawsholm 31 Possil Forth and Clyde Canal Milton Cadder Temple Gilshochill a 38 Maryhill 4 / 4 n F e d a s d /4 r a 4 a o F e River Lambhill R B d Kelvin F a Anniesland o 18 F 9 0 R 6 n /6A 1 40 r 6 u F M 30 a b g Springburn ry n h 20 i ill r R Ruchill p Kelvindale S Scotstounhill o a Balornock 41 d Possil G Jordanhill re Park C at 19 15 W es 14 te rn R 17 37 oa Old Balornock 2 d Forth and D um Kelvinside 16 Clyde b North art 11 Canal on Kelvin t Ro Firhill ad 36 ee 5 tr 1 42 Scotstoun Hamiltonhill S Cowlairs Hyndland 0 F F n e 9 Broomhill 6 F ac 0 r Maryhill Road V , a ic 6 S Pa tor Dowanhill d r ia a k D 0 F o S riv A 8 21 Petershill o e R uth 8 F 6 n F /6 G r A a u C 15 rs b R g c o u n Whiteinch a i b r 7 d e Partickhill F 4 p /4 S F a River Kelvin F 9 7 Hillhead 9 0 7 River 18 Craighall Road Port Sighthill Clyde Partick Woodside Forth and F 15 Dundas Clyde 7 Germiston 7 Woodlands Renfrew Road 10 Dob Canal F bie' 1 14 s Loa 16 n 5 River Kelvin 17 1 5 F H il 7 Pointhouse Road li 18 5 R n 1 o g 25A a t o Shieldhall F 77 Garnethill d M 15 n 1 14 M 21, 23 10 M 17 9 6 F 90 15 13 Alexandra Parade 12 0 26 Townhead 9 8 Linthouse 6 3 F Govan 33 16 29 Blyt3hswood New Town F 34, 34a Anderston © The University of Glasgo North Stobcross Street Cardonald -

New Stobhill Hospital the New Stobhill Ambulatory Care Hospital Belmont (ACH) Is Set in the Stobhill Campus

To Bishopbriggs FIF New Stobhill station E WAY New Stobhill Hospital The New Stobhill Ambulatory Care Hospital Belmont (ACH) is set in the Stobhill campus. The campus Hospital D Centre A O houses the hospital, a minor injuries unit, a R L L Marie Curie number of general and specialist mental health Walking and cycling guide 2021 HI Hospice Y facilities, and a brand new purpose-built Marie RA G Curie Cancer Care hospice. L BA A LORNOCK ROAD B The ACH provides outpatient clinics, day surgery and diagnostic services. There are hospital beds available to medics to extend the range of short B ALORNOCK ROAD stay surgical procedures offered to patients. B A L Skye House O At the main entrance there is a staffed help desk R N O and patient information points which provide C K R travel information, health promotion and other O A D advice. BELMONT ROAD Stobhill Hospital 2 new mental health wards are now on the campus. The two wards – Elgin and Appin – have space for up to 40 inpatients, with Elgin To Springburn dedicated to adult acute mental health inpatient station care and Appin focusing on older adults with functional mental health issues. Cycle Parking Entrance Rowanbank Bus stop Clinic BALORNOCK ROAD Active Travel Cycling to Work NHS Greater Glasgow & Clyde recognise that New Stobhill Hospital is well served by public transport The Cycle to Work scheme is a salary sacrifice scheme physical activity is essential for good health covering bus travel within the immediate area and available to NHS Greater Glasgow & Clyde staff*. -

Simd Analysis: Future Projections

SIMD ANALYSIS: FUTURE PROJECTIONS 1. Background and Introduction 1.1. This paper analyses the reasons behind the recent decline of deprivation in Glasgow, projects these trends towards 2015, and comments on their likely implications. It is based on a presentation made to the Community Planning Executive Group on 2nd June 2010, which itself came from a series of events held in autumn 2009/spring 2010, involving over 120 people from council and non- council organisations in Glasgow. 1.2. The gains Glasgow made in reducing its share of Scotland’s deprivation have been the result of long-term trends that have been operating over the last two or more decades. Identifying both the trends that led to the current situation, and those currently in operation which can reasonably be presented as being influential in Glasgow towards 2015, form the basis of the projections in this paper. The main indicator used has been the Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation (SIMD), and the analysis of three waves (2004, 2006 and 2009) has been supported by the use of other indicators. Looking at the absence of deprivation as well as at areas defined by deprivation includes all communities and gives a rounded analysis of the city. 1.3. The trends that have shaped the city at present are long-term and have been in operation since the 1990s, if not earlier. It follows that trends that can be identified in the present day will be those that influence the city by 2015. Their general direction has been to accelerate Glasgow’s development to its current position as a representative medium-sized western European city. -

UPPER COTTAGE FLAT 20 Swinton Drive Cardonald Glasgow G52 2EY

Telephone us on: 0141-427 0901/427 5355 • Fax: 0141-427 7446 4 Midlock Street, Ibrox, Glasgow G51 1SL• DX No: 500607, Govan UPPER COTTAGE FLAT 20 Swinton Drive Cardonald Glasgow G52 2EY Spacious Upper Cottage flat in quiet residential street, and just minutes from excellent shops, supermarkets, public transport and motorway links. Offers Over £78,000 Viewing by appointment only Solicitors 0141-427 5355 Call Centre 0141 572 7627 242464 Telephone Harter & Co on 0141 427 0901 The agents are pleased to offer to the market LOUNGE 16’5”X 12’ this lovely Upper Cottage flat, which is located KITCHEN 10’6”X 9’6” in the popular suburb of Cardonald, which lies BEDROOM ONE 10’9”X 14’ approximately five miles to the south west of BEDROOM TWO 9’10”X 12’5” Glasgow city centre. The property is within a BATHROOM 6’2”X 7’8” well-established residential street, yet is just minutes walk from a host of excellent EPC RATING D amenities on nearby Paisley Road West. There are shops and supermarkets which cater for ENTRY DATE: most day to day requirements with more By negotiation extensive shopping available in Paisley and TRAVEL DIRECTIONS: Glasgow and both Braehead and Silverburn shopping centres are a short drive away and Travelling towards Cardonald on Paisley Road West, turn right at the lights at Morrisons onto Berryknowes Road. have a large variety of shops including most Take the third left into Redpath Drive and then left into High Street outlets and popular restaurants Swinton Drive. The property is on the right hand side. -

Strengthening the Community Voice in Alcohol Licensing Decisions in Glasgow Final Report Glasgow Centre for Population Health N

Strengthening the community voice in alcohol licensing decisions in Glasgow Final Report Glasgow Centre for Population Health November 2014 Contents 1 Introduction ....................................................................................................................... 1 2 Study methods ................................................................................................................... 8 3 Views and experiences of licensing in Glasgow ............................................................... 12 4 Case studies ..................................................................................................................... 24 5 Areas for further development ........................................................................................ 32 6 Strengthening the community voice in the licensing process ......................................... 36 7 Conclusions ...................................................................................................................... 44 References ............................................................................................................................... 45 Appendix 1: LSO survey ........................................................................................................... 46 Appendix 2: LSO survey responses.......................................................................................... 50 Appendix 3: Community survey .............................................................................................