Of Bikes and Men

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Keeping St. Pete Special Thrown by Tom St. Petersburg Police Mounted Patrol Unit

JUL/AUG 2016 St. Petersburg, FL Est. September 2004 St. Petersburg Police Mounted Patrol Unit Jeannie Carlson In July, 2009 when the Boston Police t. Petersburg cannot be called a ‘one-horse Department was in the process of disbanding town.’ In fact, in addition to the quaint their historic mounted units, they donated two Shorse-drawn carriages along Beach Drive, of their trained, Percheron/Thoroughbred-cross the city has a Mounted Police Unit that patrols horses to the St. Petersburg Police Department. the downtown waterfront parks and The last time the St. Petersburg Police entertainment district. The Mounted Unit, Department employed a mounted unit was back which consists of two officers and two horses, in 1927. The donation of these horses facilitated is part of the Traffic Division of the St. Petersburg a resurgence of the unit in the bustling little Police Department as an enhancement to the metropolis that is now the City of St. Petersburg police presence downtown, particularly during in the 21st century. weekends and special events. Continued on page 28 Tom Davis and some of his finished pottery Thrown by Tom Linda Dobbs ranada Terrace resident Tom Davis is a true craftsman – even an artist. Craftsmen work with their hands and Gheads, but artists also work with their hearts according to St. Francis of Assisi. Well, Tom certainly has heart – he spends 4-6 hours per day at the Morean Center for Clay totally immersed in pottery. He even sometimes helps with the firing of ceramic creations. Imagine that in Florida’s summer heat. Tom first embraced pottery in South Korea in 1971-72 where he was stationed as a captain in the US Air Force. -

Richard's 21St Century Bicycl E 'The Best Guide to Bikes and Cycling Ever Book Published' Bike Events

Richard's 21st Century Bicycl e 'The best guide to bikes and cycling ever Book published' Bike Events RICHARD BALLANTINE This book is dedicated to Samuel Joseph Melville, hero. First published 1975 by Pan Books This revised and updated edition first published 2000 by Pan Books an imprint of Macmillan Publishers Ltd 25 Eccleston Place, London SW1W 9NF Basingstoke and Oxford Associated companies throughout the world www.macmillan.com ISBN 0 330 37717 5 Copyright © Richard Ballantine 1975, 1989, 2000 The right of Richard Ballantine to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. • All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. 1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2 A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. • Printed and bound in Great Britain by The Bath Press Ltd, Bath This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall nor, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher's prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser. -

LINK-Liste … Thema "Velomobile"

LINK-Liste … Thema "Velomobile" ... Elektromobilität Aerorider | Electric tricycle | Velomobiel Akkurad, Hersteller und Händler von Elektroleichtfahrzeugen BentBlog.de - Neuigkeiten aus der Liegerad, Trike und Velomobilszene bike-revolution - Velomobile, Österreich Birk Butterfly - alltagstaugliches Speed-HPV Blue Sky Design - HPV Blue Sky Design kit - HPV BugE Dreirad USA, Earth for Earthlings Cab-bike-D CARBIKE GmbH - "S-Pedelec-Auto" Collapsible Recumbent Tricycle Design (ICECycles) - YouTube Drymer - HPV mit Neigetechnik, NL ecoWARRIOR – 4WHEELER – eBike-Konzept von "mint-slot" ecoWARRIOR – e-Mobility – Spirit & Product Ein Fahrrad-Auto-Mobil "Made in Osnabrück" | NDR.de - Nachrichten - Niedersachsen - Osnabrück/Emsland ELF - Die amerikanische Antwort auf das Twike Elf - Wo ein Fahrrad aufs Auto trifft - USA fahrradverkleidung.de - Liegeradverkleidung, Trikeverkleidung, Dreiradverkleidung FN-Trike mit Neigetecchnik Future Cycles are Pedal-Powered Vehicles Ready to Inherit Carless Road - PSFK GinzVelo - futuristisches eBike aus den USA - Pedelecs und E-Bikes Go-One Velomobiles Goone3 - YouTube HP Velotechnik Liegeräder, Dreirad und recumbent Infos - Willkommen / Welcome HPV Sverige: Velomobil Archives ICLETTA - The culture of cycling Katanga s.r.o | WAW LEIBA - Startseite Leitra Light Electric Vehicle Association MARVELO - HPV Canada Mehrspurige ergonomische Fahrräder Mensch-Maschine-Hybrid – TWIKE - Blixxm Milan Velomobil - Die Zukunft der Mobilität Ocean Cycle HPV - GB - Manufacturer of high quality Velomobiles and recumbent bike -

![HUMAN POWERED INDIVIDUAL TRANSPORT SYSTEMS] Jack Robinson](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5604/human-powered-individual-transport-systems-jack-robinson-1455604.webp)

HUMAN POWERED INDIVIDUAL TRANSPORT SYSTEMS] Jack Robinson

[HUMAN POWERED INDIVIDUAL TRANSPORT SYSTEMS] Jack Robinson Human Powered individual transport systems Feasibility Report Project 3a (64ET6918_1213_9) By Jack Robinson 10298859 1 Contacts: | MMU [HUMAN POWERED INDIVIDUAL TRANSPORT SYSTEMS] Jack Robinson 0.0 Summary The following report aims to address the key issues surrounding human powered vehicles and analyse them in such a way as to outline the existing benefits, flaws and bring focus to potential improvements. Using the past as a spring-board, this report will critically analyse the growth and evolution of this mode of transport. Then moving forward, it will assess and criticise current options available finally looking at the potential for future growth and evolution. The further stages of this project will revolve around velomobiles; a great deal of primary and secondary research has been conducted to give the reader a full understanding of their construction and purpose. Great care has been taken to ensure that I have feedback and responses from the market that velomobiles appeal to by using specific cycling forums and contacts. Taking a critical standpoint this report utilises mistakes from the past to influence and redesign the future. 2 Contacts: | MMU [HUMAN POWERED INDIVIDUAL TRANSPORT SYSTEMS] Jack Robinson 0.1 Acknowledgements Contacts: Undercover Cycling – Go-one - [email protected] Ymte Sijbrandij – Owner of Velomobiel.nl Rollin Nothwehr – recumbent bicycle designer and manufacturer Dr Graham Sparey-Taylor – British Human Powered Forums Shimano bicycles – Bicycle and fishing company British Human Power forum - users Bentrider online forum – users The recumbent bike forums – Users Surveymonkey 3 Contacts: | MMU [HUMAN POWERED INDIVIDUAL TRANSPORT SYSTEMS] Jack Robinson Contents Table of Contents Contacts: ................................................................................................................................... -

Bicycle Paper Review Coverage in Is Secondary, and the Common Situations and Cyclist’S Health Insur- Discuss the New Bike Insurance That Ance Is Third in Line

fRee! noRTHweST cyclinG aUTHoRiTy Since 1972 www.BicyclePaPeR.com aPRil 2010 Evolutions in Commerce: Field Notes coveRaGe of the Riding Class Insurance Issues BY JOHN DU gg AN , ATTORNEY AT LAW Bike v. Car (motorist at fault): 1) As a cyclist, if you are hit by a car nbeknownst to many cyclists, in- and the accident is the driver’s fault, surance to cover cycling-related your medical bills may be covered by damagesU is generally the motorist’s Person- pieced together from al Injury Protection a combination of auto (PIP) coverage, your insurance, health insur- own automobile PIP ance and homeowners/ coverage and/or your renters insurance. Until health insurance. In recently, there was no some states PIP cover- specific “bike insur- age is optional, and uneral Home f ance” to cover situations not all drivers carry where there was no it. In Washington, the available automobile, driver’s PIP insurance emetery and medical or homeown- is primary, regardless c ers/renters insurance. of who is at fault. The This article will briefly cyclist’s PIP coverage Photo by Bicycle Paper review coverage in is secondary, and the common situations and cyclist’s health insur- discuss the new bike insurance that ance is third in line. The latter will should be available in Washington and Oregon by the time you read this. SEE INSURANCE ON PAGE 5 Photo courtesy of Sunset Hill Wade Lind of Sunset Hill Cemetery and Funeral Home in Eugene, Ore., displays his one-of-a-kind rickshaw hearse. SafeTy BY GARRETT SIMMON S hardened veterans and adrenaline junkies. -

Leg Stretchers

CYCLESENSE wanted to have a bicycle with you, no mat- exceptionally wide tires give great stability. prises winner was Scholz, who won a silver WOODSTOCK for SMALL WHEELS ter what you’re doing.” To make this irre- The tiny tires give maneuverability no medal in the 1971 USCF national champi- sistible for all sorts of travelers, he now has large-wheel mountain bike can match, and onships and hasn’t gained an ounce since. At Mike McGettigan’s festival for folding and small wheel bikes, everybody showed up. 17 “formats” of the Bike Friday. Prices the resultant package allows you to ride dif- There was a folding tour: riders took the by John Schubert range from $600 to about $3800. ficult trails with ease. commuter train from Philadelphia to Scholz was upstaged by his marketing The list of interesting designs contin- Valley Forge and rode back. Finally, there dynamo Lynette Chiang, who wowed the ues: British designer Grahame Herbert was dinner at a restaurant, where all the Adventure Cyclist reader Bob Elgroth recently reminded us in our letters crowd with a slide show of touring in showed up after a 350-mile test tour on his folders fit in a corner of the room rather column that the Bike Friday is a viable and popular choice for touring and, Cuba. She didn’t talk about her bike: she lightweight aluminum Airframe. Broo-k neatly. talked about the experiences the bike made lyn’s Peter Reich displayed his Swift folder. Overwhelmed? I sure was. If you’re thus, touring cyclists can think out of the “regular bike” box and find possible, which is what it’s all about. -

2019 Retail Price List •

22.07.2019 Orderform Euro € TRIGO retail prices including 19 VAT, valid from 01.01.2019 (VAT may vary depending on the country) old price sheets loose their validity,errors and off the shelft, while stocks last, additional accessories not mounted omissions excepted Art.No. items retail TRIGO & TRIGO UP Frame o 26200 TRIGO UP – Carmine Red/Black – above-seat steering – seat height 23”–26¼” (58.5-66.5cm) – 8-speed internal gear hub – twist 2350,00 shifter – aluminum frame and fork – Kenda 58-406mm tires with reflective sidewalls and puncture protection – Samox crankset 155mm 36T – Promax DSK-300F mech. disc brakes with parking-brake mechanism o 26100 TRIGO – Carmine Red/Black – under-seat steering – seat height 23”–26¼” (58.5-66.5cm) – 24-speed derailleur system – twist 2149,00 shifters – aluminum frame and fork – Kenda 58-406mm tires with reflective sidewalls and puncture protection – Samox crankset 155mm 50/39/30T – Promax DSK-300F mech. disc brakes with parking-brake mechanism o 26201 TRIGO NEXUS – Carmine Red/Black – under-seat steering – seat height 23”–26¼” (58.5-66.5cm) – 8-speed internal gear hub – 2350,00 twist shifter – aluminum frame and fork – Kenda 58-406mm tires with reflective sidewalls and puncture protection – Samox crankset 155mm 36T – Promax DSK-300F mech. disc brakes with parking-brake mechanism drivetrain accessories o 26068 Motor TRIGO for retrofitting - Shimano Steps E5000 - 418 Wh battery- we recommend the optional Differential as additional 1849,00 feature (limited use for people with weak leg muscles) o 25828 Motor -

Design of Urban Transit Rowing Bike (UTRB)

Design of Urban Transit Rowing Bike (UTRB) A Major Qualifying Project Report Submitted to the Faculty of the WORCESTER POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Science In Mechanical Engineering ________________ ________________ By Zebediah Tracy Claudio X. Salazar [email protected] [email protected] Date: August 2012 ___________________________________ Professor Isa Bar-On, Project Advisor Legend Red: Works contributed by Zebediah Tracy Blue: Works contributed by Claudio X. Salazar Green: Mutual works contributed by both Tracy and Salazar Abstract The objective of this project was to create a human-powered vehicle as a mode of urban transport that doubles as a complete exercise system. The project was constrained in scope by the requirement of affordability, under $1,000. This was accomplished through reducing complexity by utilizing a cable and pulley drive train, simplified tilting linkage and electric power assist in place of variable gears. This project successfully demonstrates that rowing can be the basis for effective human powered urban transport. Acknowledgments The UTRB MQP group would like to thank the following people for their assistance during this project. Thanks to professor Isa-Bar-On for her steadfast support and guidance over the full course of this endeavor. This report would not have been possible without her. Thanks to Derk F. Thys creator of the Thys Rowing Bike for his correspondence and for his foundational work on rowing geometry for biking. Thanks to Bram Smit for his correspondence regarding the Munzo TT linkage and his experience building a variety of innovative recumbents. Thanks to Bob Stuart, creator of the Car Cycle for his correspondence regarding his groundbreaking work and engineering insights. -

Conversion to an Electric Recumbent Bicycle

On your back Some articles from the periodicals of HPV-unions from Europe, Australia and Canada. 2019-2 Eu Autumn tour, photo Michael Ammann Supino2019-2 1 31 Kyle’s 6 hour and 1 hour Record Attempts Contents 42 by Kyle Lierich from Australia 38 4 To share experiences by Søren Flensted Möller, Denmark 34 Construction Report Phantom Mini-T by Tim Corbett from Australia 6 Journey to the North Cape 31 34 by Alve Henricson from Sweden 38 Soup Dragon Episode 2 by Russell Bridge in Laidback Cyclist, summer 2019 8 Racing in Räyskälä by eo Zweers, from the Dutch Ligets& 2019-3 42 A Purposeful Semi-Recumbent Tandem Tour in Western Canada 11 Recumbent activities in Finland by Peter and Serap Brown from Vancouver, Canada by Tero Linnanen, Finland 45 Recumbent activities in France in 2020 12 Cycling makes people happy by Marc Lesourd of AFV, France 6 by Alexey Ganshin, Ukraine 46 Bram Moens 35 years in business 14 Autumn tour to Alpe d’Huez by Wilfred Brahm in the Dutch Ligets& 2019-3 by Michael Ammann, Future Bike, in Infobul 210 50 Miles Kingsbury’s rst Quattro 18 Everyday mobility by Bram Smit and Willem Jan Coster in LIgfiets& 2019-3 by Werner Klomp, Recumbent bike club Vorarlberg, Austria 53 ‘Recumbent back’ 8 by Geo Searle in Laidback Cyclist, summer 2019 11 19 Literature recommendations by Heike Bunte, HPV Germany 54 Vélomobile and E-assist by Jean-Bernard Jouannel 4 20 e 24 hours of Shenington 26 by Marini of the Belgian HPV union 56 Quattrovelo with crank motor 53 50 by Denis Bodennec 19 23 On three wheels to Corfu 20 59 28 by Armin Ziegler, -

Zero-Shot Learning Problem Definition Semantic Labels Visual Feature Space

Semi-supervised Yanwei Fu Vocabulary- Leonid Sigal informed Learning Research Supervised Learning Problem Definition Supervised Learning Problem Definition Visual feature space x1 x2 Supervised Learning Problem Definition Semantic labels Visual feature space x1 airplane car unicycle tricycle x2 Supervised Learning Learning Semantic labels Visual feature space x1 airplane car unicycle tricycle x2 Supervised Learning Learning Semantic labels Visual feature space x1 airplane car unicycle tricycle x2 Supervised Learning Learning Semantic labels Visual feature space x1 airplane car unicycle tricycle x2 Supervised Learning Learning Semantic labels Visual feature space x1 airplane car unicycle tricycle x2 Supervised Learning Inference Semantic labels Visual feature space x1 airplane car unicycle tricycle x2 Supervised Learning Inference Semantic labels Visual feature space x1 airplane car unicycle tricycle x2 Supervised Learning Inference Semantic labels Visual feature space x1 airplane car unicycle tricycle x2 Zero-shot Learning Problem Definition Semantic labels Visual feature space x We do not have any visually labeled 1 instances of what these look like bicycle truck x2 Zero-shot Learning Learning Semantic label space Visual feature space x1 v1 airplane unicycle bicycle tricycle v2 car v3 truck x2 Zero-shot Learning Learning f(x) Semantic label space Visual feature space x1 v1 Word vector-feature category mapping: airplane v = f(x) unicycle bicycle tricycle v2 car v3 truck x2 Zero-shot Learning Inference f(x) Semantic label space Visual feature -

MTB Champs Give Shirts Off Their Backs to NEMBA!

The Magazine of the New England Mountain Bike Association October 1998 Number 40 SSingleingleTTrackS MTBMTB ChampsChamps givegive ShirtsShirts offoff theirtheir backsbacks toto NEMBA!NEMBA! RidingRiding withwith DogsDogs WWannaanna RRace?ace? OFF THE FRONT Keep the Rubber Side Down: Do Trail Maintenance! Blackstone Valley NEMBA Oct. 25 Callahan SF, 508-877-2028 Cape Cod & Islands NEMBA Oct. 18 Trail of Tears, 508-888-3861 Oct. 25 Otis, 508-888-3861 Nov. 8 Trail of Tears, 508-888-3861 CT NEMBA Oct.17 Branford Supply Ponds, 203.481.7184 Oct. 24 Gay City State Park, 860.529.9970 Nov. 07 Penwood State Park, 860.653.5038 TBA Trumbull area, Fairfield, 860.529.9970 GB NEMBA Oct. 17 Lynn Woods, 800-576-3622 Oct. 18 Leominster SF, 800-576-3622 Oct. 26 Great Brook Farm SP, 800-576-3622 SE MA NEMBA TBA Foxboro SF, 508-583-0067 (call for dates) Wachusett NEMBA Oct. 18 Leominster SF, 800-576-3622 (Bob Hicks) On Our Cover: Philip Keyes and Krisztina Holly take some time off at the IMBA State Rep Summit to enjoy a Tennessee trail. Tired of seeing the same folks? :) Send your pictures to: Singletracks, 2221 Main St., Acton MA 01720 2 Contents NEMBA, the New England Mountain Bike Association, is a not-for-profit 501 c 3 organi- CHAIN LETTERS —4 zation dedicated to promoting trail access and maintaining trails open for mountain bicyclists, TREADLINES —5 and to educating mountain bicyclists using these trails to ride sensitively and responsibly. HAPPENINGS Singletracks is published six times a year by the New England Mountain Bike Association Hangin’ with Team Cannondale (Krisztina Holly)—6 for the trail community, and is made possible by a commitment from member volunteers. -

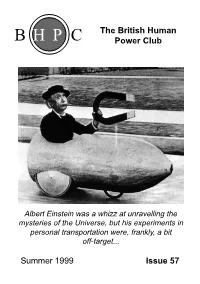

Issue 57 BHPC Newsletter - Issue 57

The British Human B H P C Power Club Albert Einstein was a whizz at unravelling the mysteries of the Universe, but his experiments in personal transportation were, frankly, a bit off-target... Summer 1999 Issue 57 BHPC Newsletter - Issue 57 Front Cover: Oi! Einstein!! NO!!! A postcard discovered by Tina in Hamburg Back Cover: Based on characters painted by some Italian geezer. Michelangelo? Mario Cipollini? I dunno... Contents Racing Events gNick, mainly 3 Touring and Socialising Events Various 3 The Six O’Clock News Dave Larrington 5 The Epistles You, Constant Reader 10 Builder’s Corner Geoff Bird, Michael Allen, Rick Valbuena, Me 12 History Lesson 1 Richard Middleton 23 History Lesson 2 Nick Bigg 25 Racing News Dave Larrington 26 Stop Press!!! Various 38 A Word From Our Sponsor Treasurer Dennis Adcock 39 Suppliers & Wants 41 Adam and Joe Tina Larrington 48 Objectives: The British Human Power Club was formed to foster all aspects of human-powered vehicles - air, land & water - for competitive, recreational and utility activities, to stimulate innovation in design and development in all spheres of HPV's, and to promote and to advertise the use of HPV's in a wide range of activities. I don’t want to drink my whisky like you do. OFFICERS Chairman & Press Officer Dave Cormie ( Home 0131 552 3148 143 East Trinity Road Edinburgh, EH5 3PP Competition Secretary gNick Green ( Home 01785 223576 267 Tixall Road Stafford, ST16 3XS E-mail: [email protected] Secretary Steve Donaldson ( Home 01224 772164 Touring Secretary Sherri Donaldson 15 Station