An Oral History of Professional Nurses' Wartime Practice in Finnmark

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Liquefied Natural Gas Production at Hammerfest: a Transforming Marine Community

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Wageningen University & Research Publications Liquefied natural gas production at Hammerfest: A transforming marine community van Bets, L. K. J., van Tatenhove, J. P. M., & Mol, A. P. J. This article is made publically available in the institutional repository of Wageningen University and Research, under article 25fa of the Dutch Copyright Act, also known as the Amendment Taverne. Article 25fa states that the author of a short scientific work funded either wholly or partially by Dutch public funds is entitled to make that work publicly available for no consideration following a reasonable period of time after the work was first published, provided that clear reference is made to the source of the first publication of the work. For questions regarding the public availability of this article, please contact [email protected]. Please cite this publication as follows: van Bets, L. K. J., van Tatenhove, J. P. M., & Mol, A. P. J. (2016). Liquefied natural gas production at Hammerfest: A transforming marine community. Marine Policy, 69, 52-61. DOI: 10.1016/j.marpol.2016.03.020 You can download the published version at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2016.03.020 Marine Policy 69 (2016) 52–61 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Marine Policy journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/marpol Liquefied natural gas production at Hammerfest: A transforming marine community Linde K.J. van Bets n, Jan P.M. van Tatenhove, Arthur P.J. Mol Environmental Policy Group, Wageningen University, PO Box 8130, 6700 EW Wageningen, The Netherlands article info abstract Article history: Global energy demand and scarce petroleum resources require communities to adapt to a rapidly Received 10 February 2016 changing Arctic environment, but as well to a transforming socio-economic environment instigated by Received in revised form oil and gas development. -

ALTA – City of the Northern Lights

Alta Cruise Port Events: Alta Soul & Blues Festival, May, - Norwegian National Day, 17. May - Midsummer Night, 23 June. Cruising season: All year. Midnight sun: 16 Mai – 26 July. Northern Lights: September - April. Dark season: 24 November – 18 January. Average temperature: May: 5, June: 10,5, July:14, August: 12,5 Useful links: www.visitalta.no, www.altahavn.no, www.finnmark.com Destination Alta | page 58 Alta Destination Alta Canyon - Sautso. Photo: Henriette Bismo Eilertsen Midsummer night. Photo: Paul Nilsen Cavzo Safari. Photo: Stefan Sanne Gargia Fjelstue: Maze and Cavzo Safari: Karasjok. Visit the Sami Theme Park with a guide Duration: 4 hours. Duration: 4-5 hours. who can tell you all the good stories. ATV/Quad – Safari- Experience the fabulous Alta A genuine Sami village. Here you can have a Duration: 10 hours 59 scenery. On this exclusive trip you can se the unique nature experience on the river boats to Finnmarksplateau and experience the beauty and the Alta Dam, or on a shorter trip over to the old Snowmobile Tour: wilderness. church. You will also get the Sami experience Duration: 4 hours. in Maze when the local host tells you about the (January – April) Try to drive you own Hunting for the Aurora Borealis: Sami way of life and their history. Bidos ( sami snowmobile. A professional, experienced Duration: 2 hours. traditional food) is served in the lavvo. guide will take care of your comfort and (January – April) Follow your guide who will safety throughout the entire trip. Good winter help you hunt for the Northern Lights. Enjoy the Northern Delights: equipment to keep you warm and good. -

Snøhvit – Wider Impacts from the LNG Process Plant at Hammerfest Trond Nilsen, Senior Researcher Norut Alta Norway

Snøhvit – Wider impacts from the LNG process plant at Hammerfest Trond Nilsen, Senior Researcher Norut Alta Norway The 5th Concept Symposium on Project Governance Valuing the Future - Public Investments and Social Return 20. – 21. September 2012 Symposium web-site: http://www.conceptsymposium.no/ Concept Research Programme: http://www.concept.ntnu.no/english/ Snøhvit ‐ Wider impacts from the LNG‐process plant in Hammerfest Resource peripheries and global production networks Trond Nilsen, Ph.D. Norut Alta This presentation leans on primary data • Trail research project for the Snøhvit Construction Phase (2003‐2008) • Trail research project for the Goliat Construction Phase and Early Operation Phase –started (2010‐2015) • Study of ripple effects in five regions, for Ministry of Petroleum and Energy (august 2012) These research projects are performed by Norut ‐Northern Research Institute, Alta. The TRP for Snøhvit was led by a steering committee with representatives for the operator Statoil, Hammerfest municipality and Finnmark county municipality. The TRP for Goliat is led by a steering committee with representatives for the operator Eni, Hammerfest municipality, Finnmark county municipality, The county Governor of Finnmark. The Snøhvit project • Development of the Snøhvit and two other gas fields in the Barents Sea at 250‐350 m water depth, 140 km north‐west of Hammerfest • Remote controlled Subsea production system on the seabed • Pipeline to shore, feeding a land based LNG plant at Melkøya Island at the shipping channel entrance into Hammerfest City • Capture and reinjection of Carbon dioxide from the wellstream • Shipping by LNG vessels (Asia, Spain, France etc.). Operator: Statoil AS Construction Phase 2002‐07 Came on stream late 2007. -

Use of Health Care in the Main Area of Sami Habitation in Norway – Catching up with National Expenditure Rates

ORIGINAL RESEARCH Use of health care in the main area of Sami habitation in Norway – catching up with national expenditure rates M Gaski, M Melhus, T Deraas, OH Førde University of Tromsø, Tromsø, Norway Submitted: 3 November 2010; Revised: 21 February 2011; Published: 31 May 2011 Gaski M, Melhus M, Deraas T, Førde OH Use of health care in the main area of Sami habitation in Norway – catching up with national expenditure rates Rural and Remote Health 11: 1655. (Online) 2011 Available: http://www.rrh.org.au A B S T R A C T Introduction: For many years political and professional concerns have centred on the health service access of Norway’s modern Indigenous Sami people. Thirty years ago, a study determined that a low rate of health expenditure on Sami patients had lead to inferior health services for the Sami people, with their average consultation rate 6 times lower than the Norwegian national average. Since 1980, there have been few studies of differences in the utilization of medical services between the Sami people and the rest of the Norwegian population. There are few official statistics relating to the ethnic category Sami. This study explored the present utilization of healthcare services among the Sami people by investigating Sami municipalities’ current expenditure on somatic hospital and specialist service. Methods: To assess the use of health care in Sami municipalities, data on expenditure of somatic hospitals and specialist services were retrieved from the Norwegian Patient Registry, and age- and sex-adjusted expenditure rates were calculated. Predominantly Sami and non-Sami municipalities were compared, as well as a comparison with the national average. -

Arctic Railway: the Vision

AN ARCTIC RAILWAY VISION The goods perspective for an Arctic railway between Rovaniemi and Kirkenes linking to a port on the Barents Sea Front page: Illustration from video produced in 2014 for the Arctic Corridor project by Region of Northern Lapland - http://arcticcorridor.fi 455 En arktisk jernbanevisjon Side 2 CONTENTS Perspectives for an Arctic railway ........................................................................................................... 5 0 SUMMARY .......................................................................................................................................... 13 1 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................................. 15 2 CURRENT MARITIME GOODS TRAFFIC IN THE NORTH ....................................................................... 16 2.1 Export .......................................................................................................................................... 16 2.2 Import .......................................................................................................................................... 18 3 THE NORTHERN SEA ROUTE ............................................................................................................... 20 3.1 The NSR and container traffic ..................................................................................................... 23 3.2 China and container cargo on the NSR ....................................................................................... -

Precambrian Stratigraphy in the Masi Area, Southwestern Finnmark, Norway

Precambrian Stratigraphy in the Masi Area, Southwestern Finnmark, Norway ARNE SOLLI Solli, A. 1983: Precambrian stratigraphy in the Masi area, southwestern Finnmark, Norway. Norges geol. Unders. 380, 97-105. The rocks in the Masi areaconsistsof acomformable stratigraphicsequencecontain ing three formations. The lowest is the Gål'denvarri formation, mainly containing metamorphic basic volcanics. Above this is the Masi Quartzite with a conglomerate at its base. The upper formation in the Masi area is the Suoluvuobmi formation containing metamorphic basic volcanics, metagabbros, mica schist, graphitic schist and albite fels. The eastern part of the area is dominated by granites which have an intrusive relationship to all three formations. Remnants of the Archean basement situated further to the east probably occur within the younger granites. Nothing conclusive can be said about the ages of the rocks, but for the Gål'denvarri formation an Archean age is considered most probable. The ages of the Meisi Quartzite and Suoluvuobmi formation may be Svecokarelian, but based on correlation with rocks in Finland, Archean ages also seem likely for these units. A. Solli, Norges geologiske undersokelse, P.0.80x 3006, N-7001 Trondheim, Norway. Introduction The central part of Finnmarksvidda is occupied by a dome structure of Archean granitic gneisses (Fig. 1). On each side of the dome are supracrustal rocks. To the east is the Karasjok region, and to the west is the Kautokeino- Masi region with the same types of rocks even though no direct correlation has yet been established between the two regions. Greenstones, quartzites and mica schist are the dominating rock types. A brief summary of the geo logy of Finnmarksvidda is given by Skålvoll (1978), and Fig. -

Getting Food During the German Occupation of Western Finnmark (1940–1944)

Getting food during the German occupation of Western Finnmark (1940–1944) Yaroslav Bogomolov In this article the author describes the food supply in the western part of Finnmark County. Despite the fact that the authorities tried to control the food supplies and secure equal access to food for all inhabitants, food distribution was never equal and civilians had to work hard and use their imagination in order to get some food to eat. 1 Introduction Nutrition as a topic was absent in historical studies for a long time. Food as a part of our daily routine is an almost invisible thing for historians. The changes have started to happen about two decades ago. As Clarkson and Crawford write “...nutritional history is moving out of the cellar”1. Today quite a lot of books have been published about human nutrition during various historical periods, but this work is still far from being finished. Aside from historical reports on Norwegians’ diet during the war2, nutrition on its own was very seldom a subject of interest for Norwegian authors3. This seems to me to be a bit strange. As we can see in articles by Mølmann et al. (2015) and Khatanzeiskaya (2015), insufficient nutrition was a cause of various health problems, so it is very important to study nutrition during the times of crisis. The topic of nutrition seems to me to be very comprehensive. It includes people’s daily diet, cuisine, ways of getting food, scientific approach to food (what kind of food is supposed to be healthy and how much of it is needed for each individual and so on) and much more. -

DOMINANT ETHNIC GROUPS in EUROPE, 1850-1940 · Ethnic Groups and Language Rights Volume III

COMPARATIVE STUDIES ON GOVERNMENTS AND NON 1/ .f:( - DOMINANT ETHNIC GROUPS IN EUROPE, 1850-1940 · Ethnic Groups and Language Rights Volume III ~., i . 1 . Edited by { SERGIJ VILFAN in collaboration with 1 GUDMUND SANDVIK and LODE WILS 1. f' 1 ~... ,' Non-existent Sami Language Rights in Norway, 1850--1940 GUDMUND SANDVIK European Science Foundation NEW YORK UNIVERSITY PRESS DARTMOUTH 128 .., 13 Non-existent Sami Language Rights in Norway, 1850-1940 GUDMUND SANDVIK Background The Samis are an ethnic minority in the Nordic countries and in Russia. According to more or less reliable censuses, they number today about 40 000 in Norway (1 per cent of the total population), 20000 in Sweden (0.25 per cent), 4500 in Finland (0.1 per cent) and 2000 on the Kola peninsula in Russia. Only Finland has had a regular ethnic census. The Samis call themselves sapmi or sabmi. It is only recently (after 1950) that this name has been generally accepted in the Nordic countries (singular same, plural samer). Tacitus wrote about fenni;1 Old English had finnas;2 Historia NorvegitE (History of Norway) written about P80 had finni,3 and the Norse word was {imzar. 4 In medieval Icelandic and Norwegian literature, Finnmork was the region in northern Scandinavia where the Samis lived. The northern most Norwegian fylke (county) of today, Finnmark, takes jts name from the huge medieval Finnmork. But Samis of today still use the name S4pnzi for the entire region where they live (See Map 13.1, ;].. which "shows S4pmiwith state frontiers and some Sami centres). 'Finner' is accordingly an authentic Norwegian name. -

Downloaded From

Connecting and correcting : a case study of Sami healers in Porsanger Miller, B.H. Citation Miller, B. H. (2007, June 20). Connecting and correcting : a case study of Sami healers in Porsanger. CNWS/LDS Publications. CNWS Publicaties, Leiden. Retrieved from https://hdl.handle.net/1887/12088 Version: Corrected Publisher’s Version Licence agreement concerning inclusion of doctoral License: thesis in the Institutional Repository of the University of Leiden Downloaded from: https://hdl.handle.net/1887/12088 Note: To cite this publication please use the final published version (if applicable). Connecting and Correcting A Case Study of Sami Healers in Porsanger Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van Doctor aan de Universitet Leiden, op gezag van Rector Magnificus prof.mr. P.F. van der Heijden, volgens besluit van het College voor Promoties te verdedigen op woensdag 20 juni 2007 klokke 16.15 uur door Barbara Helen Miller geboren te Oconomowoc, Wisconsin, USA in 1949 Promotiecommissie: Promotor: Prof. Dr. J.G. Oosten Referent: Mw. Dr. N.J.M. Zorgdrager Overige leden: Prof. Dr. P.J. Pels Prof. Dr. P.J.M. Nas Mw. Dr. S.W.J. Luning Connecting and Correcting A Case Study of Sami Healers in Porsanger CNWS Publications Leiden CNWS Publications, Vol. 151 CNWS publishes books and journals which advance scholarly research in Asian, African and Amerindian Studies. CNWS Publications is part of the Research School of Asian, African and Amerindian Studies (CNWS) at Leiden University, The Netherlands. All correspondence should be addressed to: CNWS Publications c/o Research School CNWS Leiden University PO Box 9515, 2300 RA Leiden The Netherlands. -

Indigenous Internal Selfdetermination in Australia and Norway

i Indigenous internal self-determination in Australia and Norway by Pia Solberg A thesis in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Humanities & Languages Faculty of Arts & Social Sciences The University of New South Wales October 2016 iv Table of Contents Acknowledgments.........................................................................................................vii Language and terminology.............................................................................................ix Abstract..........................................................................................................................x Introduction.................................................................................................................11 Approaches to the problem.............................................................................13 Why compare with Norway and the Sami?.....................................................17 My approach..................................................................................................20 The structure of this thesis..............................................................................24 PART ONE: HISTORY MATTERS.............................................................................26 Chapter One. Early Colonisation...........................................................................27 Introduction........................................................................................................27 Sapmi: -

Porsanger Kommune

Kartlegging av radon i Porsanger kommune Radon 2000/2001 Vinteren 2000/2001 ble det gjennomført en fase 1-kartlegging av radon i inneluft i Porsanger kommune, i forbindelse med den landsomfattende undersøkelsen ”Radon 2000/2001”. En andel på 11 % av kommunens husstander deltok i kartleggingen, og det ble funnet at 4 % av disse har en radonkonsentrasjon som er høyere enn anbefalt tiltaksnivå på 200 Bq/m3 luft. Deler av Porsanger har et radonproblem, og anbefalt oppfølging av kommunen kan deles i tre kategorier avhengig av problemomfang. I Mikkeljord er flere enn 20 % av målingene over tiltaksgrensen, noe som tilsier en høy sannsynlighet for høye radonverdier. Statens strålevern anbefaler oppfølgende målinger i alle boliger som har leilighet eller oppholdsrom i 1. etasje eller underetasje i dette området. I området nord for Mikkeljord langs Porsangen forbi Olderfjord, i området sør for Lakselv langs E6 forbi Porsangmoen og Skoganvarre, samt i Børselv viser mellom 5 % og 20 % av målingene verdier over 200 Bq/m3. Sannsynligheten for høye radonverdier er her middels høy, og det anbefales å gjøre oppfølgende målinger i utvalgte boliger i disse områdene. I de resterende delene av Porsanger kommune ligger under 5 % av målingene over tiltaksgrensen, og sannsynligheten for høye radonverdier er lav. I disse områdene kan oppfølgingen begrenses til generell informasjon og veiledning til innbyggerne. Line Ruden Gro Beate Ramberg Katrine Ånestad Terje Strand Kartlegging av radon i Porsanger kommune Mer generell informasjon om radon finnes 1. INNLEDNING på Strålevernets radonsider: http://radon.nrpa.no. 1.1 Om radon Radon (222Rn) er et radioaktivt stoff som dannes naturlig ved desintegrasjon av 1.2 Bakgrunn for prosjektet radium (226Ra), og som finnes i varierende I forbindelse med Nasjonal kreftplan, som mengder i all berggrunn og jordsmonn. -

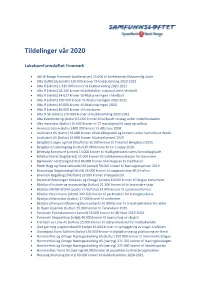

Tildelinger Vår 2020

Tildelinger vår 2020 Lokalsamfunnsløftet Finnmark • ADHD Norge Finnmark (konferanser) 25.000 til konferansen Elevvennlig skole. • Alta Golfklubb (idrett) 120.000 kroner til klubbutvikling 2020-2022. • Alta IF (idrett) 1.410.000 kroner til klubbutvikling 2020-2022. • Alta IF (idrett) 28.200 kroner til deltakelse i nasjonal serie håndball. • Alta IF (idrett) 34.627 kroner til Altaturneringen i håndball. • Alta IF (idrett) 350.000 kroner til Altaturneringen 2020-2022. • Alta IF (idrett) 40.000 kroner til Altaturneringen 2020. • Alta IF (idrett) 86.000 kroner til treerbaner. • Alta IF Ski (idrett) 270.000 kroner til klubbutvikling 2020-2022. • Alta Kvenforening (kultur)15.000 kroner til kulturelt innslag under vinterfestivalen. • Alta mannskor (kultur) 10.000 kroner til 17.mai dugnad til sang og spilling. • Aronnesrocken (kultur) 400.000 kroner til Alta Live 2020. • Audioland AS (kultur) 35.000 kroner til bestillingsverk og konsert under Sami Music Week. • Audioland AS (kultur) 65.000 kroner til påskekonsert 2020. • Bergsfjord Jeger og Fisk (friluftsliv) 10.000 kroner til Fiskefest Bergsfjord 2020. • Bergsfjord Utviklingslag (kultur)35.000 kroner til Liv i Loppa 2020. • Berlevåg Kommune (annet) 13.000 kroner til frivillighetssentralens formiddagskafé. • Billefjord Idrettslag (idrett) 25.000 kroner til radiokommunikasjon for dommere. • Bjørnevatn Idrettslag (idrett) 86.000 kroner til innkjøp av to treerbaner. • Bloch Bygg og Materialhandel AS (annet) 50.000 kroner til Næringslivsprisen 2019. • Bossekopp Ungdomslag (idrett) 26.000 kroner til oppgradering i BUL-hallen. • Brennelv Bygdelag (friluftsliv) 29.500 kroner til løypeslodd. • Brystkreftforeningen Kirkenes og Omegn (annet) 10.000 kroner til fatigue minisminar. • Båtsfjord historie og museumslag (kultur) 21.500 kroner til to brannsikre skap.