Animating Hierarchy: Disney and the Globalization of Capitalism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Racism and Stereotypes: Th Movies-A Special Reference to And

People’s Democratic Republic of Algeria Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific ResearchResearch Larbi Ben M’h idi University-Oum El Bouaghi Faculty of Letters and Languages Department of English Racism and Stereotypes: The Image of the Other in Disney’s Movies-A Special Reference to Aladdin , Dumbo and The Lion King A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the D egree of Master of Arts in Anglo-American Studies By: Abed Khaoula Board of Examiners Supervisor: Hafsa Naima Examiner: Stiti Rinad 2015-2016 Dedication To the best parents on earth Ouiza and Mourad To the most adorable sisters Shayma, Imène, Kenza and Abir To my best friend Doudou with love i Acknowledgements First of all,I would like to thank ‘A llah’ who guides and gives me the courage and Patience for conducting this research.. I would like to express my deep appreciation to my supervisor Miss Hafsa Naima who traced the path for this dissertation. This work would have never existed without her guidance and help. Special thanks to my examiner Miss Stiti Rinad who accepted to evaluate my work. In a more personal vein I would like to thank my mother thousand and one thanks for her patience and unconditional support that facilitated the completion of my graduate work. Last but not least, I acknowledge the help of my generous teacher Mr. Bouri who believed in me and lifted up my spirits. Thank you for everyone who believed in me. ii ا ا أن اوات ا اد ر ر دة اطل , د ه اوات ا . -

Disney Syllabus 12

WS 325: Disney: Gender, Race, and Empire Women Studies Oregon State University Fall 2012 Thurs., 2:00-3:20 WLKN 231 (3 credits) Dr. Patti Duncan 266 Waldo Hall Office Hours: Mon., 2:00-3:30 and by appt email: [email protected] Graduate Teaching Assistant: Chelsea Whitlow [OFFICE LOCATION] Office Hours: Mon./Wed., 9:30-11:00 email: [email protected] __________________________________________________________________________________________________ CATALOGUE DESCRIPTION Introduces key themes and critical frameworks in feminist film theories and criticism, focused on recent animated Disney films. Explores constructions of gender, race, class, sexuality, and nation in these representations. (H) (Bacc Core Course) PREREQUISITES: None, but a previous WS course is helpful. COURSE DESCRIPTION In this discussion-oriented course, students will explore constructions of gender, race, class, sexuality, and nation in the recent animated films of Walt Disney. By examining the content of several Disney films created within particular historical and cultural contexts, we will develop and expand our understanding of the cultural productions, meanings, and 1 intersections of racism, sexism, classism, colonialism, and imperialism. We will explore these issues in relation to Disney’s representations of concepts such as love, sex, family, violence, money, individualism, and freedom. Also, students will be introduced to concepts in feminist film theory and criticism, and will develop analyses of the politics of representation. Hybrid Course This is a hybrid course, where approximately 50% of the course will take place in a traditional face-to-face classroom and 50% will be delivered via Blackboard, your online learning community, where you will interact with your classmates and with the instructor. -

Here Comes Television

September 1997 Vol. 2 No.6 HereHere ComesComes TelevisionTelevision FallFall TVTV PrPrevieweview France’France’ss ExpandingExpanding ChannelsChannels SIGGRAPHSIGGRAPH ReviewReview KorKorea’ea’ss BoomBoom DinnerDinner withwith MTV’MTV’ss AbbyAbby TTerkuhleerkuhle andand CTW’CTW’ss ArleneArlene SherShermanman Table of Contents September 1997 Vol. 2, . No. 6 4 Editor’s Notebook Aah, television, our old friend. What madness the power of a child with a remote control instills in us... 6 Letters: [email protected] TELEVISION 8 A Conversation With:Arlene Sherman and Abby Terkuhle Mo Willems hosts a conversation over dinner with CTW’s Arlene Sherman and MTV’s Abby Terkuhle. What does this unlikely duo have in common? More than you would think! 15 CTW and MTV: Shorts of Influence The impact that CTW and MTV has had on one another, the industry and beyond is the subject of Chris Robinson’s in-depth investigation. 21 Tooning in the Fall Season A new splash of fresh programming is soon to hit the airwaves. In this pivotal year of FCC rulings and vertical integration, let’s see what has been produced. 26 Saturday Morning Bonanza:The New Crop for the Kiddies The incurable, couch potato Martha Day decides what she’s going to watch on Saturday mornings in the U.S. 29 Mushrooms After the Rain: France’s Children’s Channels As a crop of new children’s channels springs up in France, Marie-Agnès Bruneau depicts the new play- ers, in both the satellite and cable arenas, during these tumultuous times. A fierce competition is about to begin... 33 The Korean Animation Explosion Milt Vallas reports on Korea’s growth from humble beginnings to big business. -

The Lion King Audition Monologues

Audition Monologues Choose ONE of the monologues. This is a general call; the monologue you choose does not affect how you will be cast in the show. We are listening to the voice, character development, and delivery no matter what monologue you choose. SCAR Mufasa’s death was a terrible tragedy; but to lose Simba, who had barely begun to live... For me it is a deep personal loss. So, it is with a heavy heart that I assume the throne. Yet, out of the ashes of this tragedy, we shall rise to greet the dawning of a new era... in which lion and hyena come together, in a great and glorious future! MUFASA Look Simba. Everything the light touches is our kingdom. A king's time as ruler rises and falls like the sun. One day, Simba, the sun will set on my time here - and will rise with you as the new king. Everything exists in a delicate balance. As king, you need to understand that balance, and respect for all creatures-- Everything is connected in the great Circle of Life. YOUNG SIMBA Hey Uncle Scar, guess what! I'm going to be king of Pride Rock. My Dad just showed me the whole kingdom, and I'm going to rule it all. Heh heh. Hey, Uncle Scar? When I'm king, what will that make you? {beat} YOUNG NALA Simba, So, where is it? Better not be any place lame! The waterhole? What’s so great about the waterhole? Ohhhhh….. Uh, Mom, can I go with Simba? Pleeeez? Yay!!! So, where’re we really goin’? An elephant graveyard? Wow! So how’re we gonna ditch the dodo? ZAZU (to Simba) You can’t fire me. -

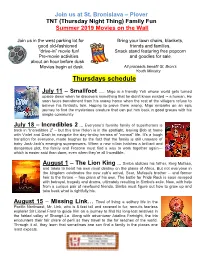

Thursdays Schedule

Join us at St. Bronislava – Plover TNT (Thursday Night Thing) Family Fun Summer 2019 Movies on the Wall Join us in the west parking lot for Bring your lawn chairs, blankets, good old-fashioned friends and families. “drive-in” movie fun! Snack stand featuring free popcorn Pre-movie activities and goodies for sale. about an hour before dusk. Movies begin at dusk. All proceeds benefit St. Bron’s Youth Ministry Thursdays schedule July 11 – Smallfoot … Migo is a friendly Yeti whose world gets turned upside down when he discovers something that he didn't know existed -- a human. He soon faces banishment from his snowy home when the rest of the villagers refuse to believe his fantastic tale. Hoping to prove them wrong, Migo embarks on an epic journey to find the mysterious creature that can put him back in good graces with his simple community July 18 – Incredibles 2 … Everyone’s favorite family of superheroes is back in “Incredibles 2” – but this time Helen is in the spotlight, leaving Bob at home with Violet and Dash to navigate the day-to-day heroics of “normal” life. It’s a tough transition for everyone, made tougher by the fact that the family is still unaware of baby Jack-Jack’s emerging superpowers. When a new villain hatches a brilliant and dangerous plot, the family and Frozone must find a way to work together again— which is easier said than done, even when they’re all Incredible. August 1 – The Lion King … Simba idolizes his father, King Mufasa, and takes to heart his own royal destiny on the plains of Africa. -

UPC Platform Publisher Title Price Available 730865001347

UPC Platform Publisher Title Price Available 730865001347 PlayStation 3 Atlus 3D Dot Game Heroes PS3 $16.00 52 722674110402 PlayStation 3 Namco Bandai Ace Combat: Assault Horizon PS3 $21.00 2 Other 853490002678 PlayStation 3 Air Conflicts: Secret Wars PS3 $14.00 37 Publishers 014633098587 PlayStation 3 Electronic Arts Alice: Madness Returns PS3 $16.50 60 Aliens Colonial Marines 010086690682 PlayStation 3 Sega $47.50 100+ (Portuguese) PS3 Aliens Colonial Marines (Spanish) 010086690675 PlayStation 3 Sega $47.50 100+ PS3 Aliens Colonial Marines Collector's 010086690637 PlayStation 3 Sega $76.00 9 Edition PS3 010086690170 PlayStation 3 Sega Aliens Colonial Marines PS3 $50.00 92 010086690194 PlayStation 3 Sega Alpha Protocol PS3 $14.00 14 047875843479 PlayStation 3 Activision Amazing Spider-Man PS3 $39.00 100+ 010086690545 PlayStation 3 Sega Anarchy Reigns PS3 $24.00 100+ 722674110525 PlayStation 3 Namco Bandai Armored Core V PS3 $23.00 100+ 014633157147 PlayStation 3 Electronic Arts Army of Two: The 40th Day PS3 $16.00 61 008888345343 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed II PS3 $15.00 100+ Assassin's Creed III Limited Edition 008888397717 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft $116.00 4 PS3 008888347231 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed III PS3 $47.50 100+ 008888343394 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed PS3 $14.00 100+ 008888346258 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Brotherhood PS3 $16.00 100+ 008888356844 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Revelations PS3 $22.50 100+ 013388340446 PlayStation 3 Capcom Asura's Wrath PS3 $16.00 55 008888345435 -

Animated Stereotypes –

Animated Stereotypes – An Analysis of Disney’s Contemporary Portrayals of Race and Ethnicity Alexander Lindgren, 36761 Pro gradu-avhandling i engelska språket och litteraturen Handledare: Jason Finch Fakulteten för humaniora, psykologi och teologi Åbo Akademi 2020 ÅBO AKADEMI – FACULTY OF ARTS, PSYCHOLOGY AND THEOLOGY Abstract for Master’s Thesis Subject: English Language and Literature Author: Alexander Lindgren Title: Animated Stereotypes – An Analysis of Disney’s Contemporary Portrayals of Race and Ethnicity Supervisor: Jason Finch Abstract: Walt Disney Animation Studios is currently one of the world’s largest producers of animated content aimed at children. However, while Disney often has been associated with themes such as childhood, magic, and innocence, many of the company’s animated films have simultaneously been criticized for their offensive and quite problematic take on race and ethnicity, as well their heavy reliance on cultural stereotypes. This study aims to evaluate Disney’s portrayals of racial and ethnic minorities, as well as determine whether or not the nature of the company’s portrayals have become more culturally sensitive with time. To accomplish this, seven animated feature films produced by Disney were analyzed. These analyses are of a qualitative nature, with a focus on imagology and postcolonial literary theory, and the results have simultaneously been compared to corresponding criticism and analyses by other authors and scholars. Based on the overall results of the analyses, it does seem as if Disney is becoming more progressive and culturally sensitive with time. However, while most of the recent films are free from the clearly racist elements found in the company’s earlier productions, it is quite evident that Disney still tends to rely heavily on certain cultural stereotypes. -

©2014 Disney ©2014 Disney Enterprises, Inc

©2014 Disney ©2014 Disney Enterprises, Inc. All Rights Reserved. Disney.com/Neverbeast STORY Story Artists TROY ADOMITIS JOHN D. ANDERSON TOM BERNARDO EMMANUEL DELIGIANNIS RYAN GREEN DAVID KNOTT JIHYUN PARK ROBB PRATT LYNDON RUDDY SEUNG-HYUN OH SHANE ZALVIN Creative Development ............................VICKI LETIZIA PRODUCTION Production Managers ..................... JARED HEISTERKAMP JASON I. STRAHS Directed by ........................................ STEVE LOTER Production Coordinators ........................JILLIAN GOMEZ Produced by ...........................MICHAEL WIGERT, p.g.a. AMY PIJANOWSKI Executive Producer .............................JOHN LASSETER BARBRA PUSHIES Story by ........................................... STEVE LOTER ALLIE RUSSELL and TOM ROGERS Production Finance Lead ........................ TANYA SELLERS Screenplay by .................................... TOM ROGERS Production Secretary ....................... BRIAN MCMENAMIN and ROBERT SCHOOLEY & MARK MCCORKLE DESIGN and KATE KONDELL Original Score Composed by ..................... JOEL MCNEELY Character Design .............................RITSUKO NOTANI Editor ..........................................MARGARET HOU ELSA CHANG Art Director .....................................ELLEN JIN OVER DAVID COLMAN Animation Supervisor .................... MICHAEL GREENHOLT BOBBY CHIU Head of Story ................................. LAWRENCE GONG KEI ACEDERA CG Supervisor ...................................... MARC ELLIS Associate Producer ......................TIMOTHY -

Enjoy the Magic of Walt Disney World All Year Long with Celebrations Magazine! Receive 6 Issues for $29.99* (Save More Than 15% Off the Cover Price!) *U.S

Enjoy the magic of Walt Disney World all year long with Celebrations magazine! Receive 6 issues for $29.99* (save more than 15% off the cover price!) *U.S. residents only. To order outside the United States, please visit www.celebrationspress.com. To subscribe to Celebrations magazine, clip or copy the coupon below. Send check or money order for $29.99 to: YES! Celebrations Press Please send me 6 issues of PO Box 584 Celebrations magazine Uwchland, PA 19480 Name Confirmation email address Address City State Zip You can also subscribe online at www.celebrationspress.com. On the Cover: “Splash!”, photo by Tim Devine Issue 24 Taking the Plunge on 42 Contents Splash Mountain Letters ..........................................................................................6 Calendar of Events ............................................................ 8 Disney News & Updates................................................10 MOUSE VIEWS ......................................................... 15 Guide to the Magic O Canada by Tim Foster............................................................................16 50 Explorer Emporium by Lou Mongello .....................................................................18 Hidden Mickeys by Steve Barrett .....................................................................20 Photography Tips & Tricks by Tim Devine .........................................................................22 Music in the Parks Pin Trading & Collecting by John Rick .............................................................................24 -

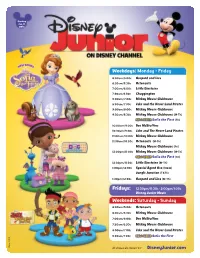

Disneyjunior.Com SM

Starting Jan. 11 2013 Weekdays: Monday - Friday 6:00am/5:00c Gaspard and Lisa 6:30am/5:30c Octonauts 7:00am/6:00c Little Einsteins 7:30am/6:30c Chuggington 8:00am/7:00c Mickey Mouse Clubhouse 8:30am/7:30c Jake and the Never Land Pirates 9:00am/8:00c Mickey Mouse Clubhouse 9:30am/8:30c Mickey Mouse Clubhouse (M-Th) NEW SERIES Sofia the First (Fri) 10:00am/9:00c Doc McStuffins 10:30am/9:30c Jake and The Never Land Pirates 11:00am/10:00c Mickey Mouse Clubhouse 11:30am/10:30c Octonauts (M-Th) Mickey Mouse Clubhouse (Fri) 12:00pm/11:00c Mickey Mouse Clubhouse (M-Th) NEW SERIES Sofia the First (Fri) 12:30pm/11:30c Little Einsteins (M-Th) 1:00pm/12:00c Special Agent Oso (M&W) Jungle Junction (T&Th) 1:30pm/12:30c Gaspard and Lisa (M-Th) Fridays: 12:30pm/11:30c - 2:00pm/1:00c Disney Junior Movie Weekends: Saturday - Sunday 6:00am/5:00c Octonauts 6:30am/5:30c Mickey Mouse Clubhouse 7:00am/6:00c Doc McStuffins 7:30am/6:30c Mickey Mouse Clubhouse 8:00am/7:00c Jake and the Never Land Pirates 8:30am/7:30c NEW SERIES Sofia the First ©Disney J#5849 ©Disney J#5849 All shows are rated TV-Y DisneyJunior.com SM Weekdays: Monday - Friday Weekends: Saturday & Sunday 6:00am/5:00c Koala Brothers 6:00am/5:00c The Little Mermaid 6:30am/5:30c Stanley 6:30am/5:30c Jungle Cubs 7:00am/6:00c Timmy Time 7:00am/6:00c Handy Manny 7:30am/6:30c 3rd & Bird 7:30am/6:30c Chuggington 8:00am/7:00c Imagination Movers 8:00am/7:00c Higglytown Heroes 8:30am/7:30c Charlie and Lola 8:30am/7:30c Charlie and Lola 9:00am/8:00c JoJo’s Circus 9:00am/8:00c Little Einsteins 9:30am/8:30c -

1 for IMMEDIATE RELEASE February 7, 2012 the WALT DISNEY COMPANY REPORTS FIRST QUARTER EARNINGS BURBANK, Calif. – the Walt

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE February 7, 2012 THE WALT DISNEY COMPANY REPORTS FIRST QUARTER EARNINGS BURBANK, Calif. – The Walt Disney Company today reported earnings for its first fiscal quarter ended December 31, 2011. Diluted earnings per share (EPS) for the quarter increased 18% to $0.80 from $0.68 in the prior-year quarter. “We’re off to a good start in this fiscal year executing on our ongoing strategy, deriving greater value from our brands – Disney, Pixar, Marvel, ESPN and ABC – in the U.S. and around the globe,” said Disney President and CEO Robert A. Iger. “We are confident that our commitment to creating and providing exceptional family entertainment on multiple platforms continues to position us to deliver long- term shareholder value.” The following table summarizes the first quarter results for fiscal 2012 and 2011 (in millions, except per share amounts): Quarter Ended Dec. 31, Jan. 1, 2011 2011 Change Revenues $ 10,779 $ 10,716 1 % Segment operating income (1) $ 2,444 $ 2,208 11 % Net income (2) $ 1,464 $ 1,302 12 % Diluted EPS (2) $ 0.80 $ 0.68 18 % Cash provided by operations $ 1,734 $ 1,119 55 % Free cash flow (1) $ 1,100 $ (94 ) >100 % (1) Aggregate segment operating income and free cash flow are non-GAAP financial measures. See the discussion of non-GAAP financial measures below. (2) Reflects amounts attributable to shareholders of The Walt Disney Company, i.e. after deduction of noncontrolling (minority) interests. 1 SEGMENT RESULTS The following table summarizes the first quarter segment operating results for fiscal 2012 and 2011 (in millions): Quarter Ended Dec. -

Big Media, Little Kids: Media Consolidation & Children's

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 475 660 PS 031 233 AUTHOR Glaubke, Christina Romano; Miller, Patti TITLE Big Media, Little Kids: Media Consolidation & Children's Television Programming. INSTITUTION Children Now, Oakland, CA. PUB DATE 2003-05-21 NOTE 17p.; Additional support provided by the Philadelphia Foundation and Atlantic Philanthropies. AVAILABLE FROM Children Now, 1212 Broadway, Suite 530, Oakland, CA 94612. Tel: 510-763-2444; Fax: 510-763-1974; e-mail: [email protected]; Web site: http://www.childrennow.org. For full text: http://www.childrennow.org/media/fcc-03/fcc-ownership-study- 05-21-03.pdf. PUB TYPE Reports Research (143) EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Centralization; *Childrens Television; Comparative Analysis; Mergers; *Programming (Broadcast); Television Research IDENTIFIERS California (Los Angeles); Federal Communications Commission ABSTRACT The Federal Communications Commission is currently considering modifying or eliminating existing media ownership rules. Children's advocates are concerned that any changes to these rules could negatively affect the already limited amount and types of programming available for children. Children Now conducted the first study to examine the availability and diversity of children programming in an increasingly consolidated media marketplace. Los Angeles was selected as a case study for this research because it is the second largest media market in the country, and two duopolies now exist among its television stations. The study compared the children's programming schedules from 1998, when the market's seven major commercial broadcast television stations were owned by seven different companies, to 2003, after consolidation reduced the number to five. The findings suggest that changes to the current ownership policies will have a serious impact on the availability and diversity of children's programming.