Doktori (Phd) Értekezés

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Neil Macgregor, a History of the World in 100 Objects

TERMINUS tom 15 (2013), z. 2 (27), s. 275–282 doi:10.4467/20843844TE.13.016.1573 www.ejournals.eu/Terminus NCEIL MA GREGOR, A HISTORY OF THE WORLD IN 100 OBJECTS, FIRST PUBLISHED IN PRINT IN OCTOBER 2010 BY ALLEN LANE IMPRINT OF PENGUIN BOOKS, PP. 640 Edition used for the review: Kindle Edition, 6 October 2011, Penguin KAJA SZYMAńSKA Uniwersytet Jagielloński, Kraków Only stable, rich and powerful states can commission great art and architectu- re that, unlike text or language, can be instantly understood by anyone – a gre- at advantage in multilingual empires. Neil MacGregor1 The book A History of the World in 100 Objects is a result of a multi-plat- form BBC and British Museum joint enterprise released in 2010. It of- fered an innovative look at history and the role of a museum, and was a great success in popularising knowledge, and history in particular. The whole project involved 550 heritage partners and comprised several me- dia outlets: a six-month long series of daily broadcasts by BBC Radio 4, a website through which individual users and other institutions could also contribute, uploading objects of their own choice, and finally, the book to which this review specifically relates. The radio programme drew 4 million listeners and podcast downloads amounted to over 10 million during the 1 N. MacGregor, loc. 3542/9008. Publikacja objęta jest prawem autorskim. Wszelkie prawa zastrzeżone. Kopiowanie i rozpowszechnianie zabronione. Publikacja przeznaczona jedynie dla klientów indywidualnych. Zakaz rozpowszechniania i udostępniania w serwisach bibliotecznych 276 Kaja Szymańska following year (only just over 5.7 million from the UK). -

AND8002/D Eclinps™, Eclinps Lite™, Eclinps Plus™, Eclinps MAX™, and Gigacomm™ Marking and Ordering Information Guide

查询AND8003-D供应商 捷多邦,专业PCB打样工厂,24小时加急出货 AND8002/D ECLinPS,ECLinPSLite, ECLinPSPlus, ECLinPSMAX,and GigaCommMarkingand OrderingInformationGuide http://onsemi.com APPLICATION NOTE Prepared by: Paul Shockman ON Semiconductor HFPD Applications Engineer Introduction This application note describes the device markings and This application note also includes the following ordering information for the following ON Semiconductor appendices: families (refer to the respective family data book for family • Appendix 1: ECLinPS Device Order Number and information): Marking tables. • ECLinPS • Appendix 2: ECLinPS Lite Device Order Number and • ECLinPS Lite Marking tables. • ECLinPS Plus • Appendix 3: ECLinPS Plus Device Order Number and • ECLinPS MAX Marking tables. • GigaComm • Appendix 4: ECLinPS MAX Device Order Number Note that data sheet information takes precedence over and Marking Tables. this application note if there are any differences. • Appendix 5: GigaComm Device Order Number and Marking tables. Application Note Information This application note is divided into the following sections: • Section 1: Data Sheet Marking Diagrams − The diagrams provide identification, traceability, date, and packaging information. • Section 2: Data Sheet Ordering Information Tables − The tables list the device order numbers for every available device configuration. Semiconductor Components Industries, LLC, 2005 1 Publication Order Number: April, 2005 − Rev. 6 AND8002/D AND8002/D SECTION 1: Data Sheet Marking Diagrams Device Marking Examples • Code 1. Circuit Identification Code The marking format is dependent upon the device • Code 2. Temperature Compensation Code package, and larger device packages allow the inclusion of • Code 3. Family Identification Code more information on the face of the device. On the larger • packages where marking space permits, the Pb Free Code 4. -

From Small States to Universalism in the Pre-Islamic Near East

REVOLUTIONIZING REVOLUTIONIZING Mark Altaweel and Andrea Squitieri and Andrea Mark Altaweel From Small States to Universalism in the Pre-Islamic Near East This book investigates the long-term continuity of large-scale states and empires, and its effect on the Near East’s social fabric, including the fundamental changes that occurred to major social institutions. Its geographical coverage spans, from east to west, modern- day Libya and Egypt to Central Asia, and from north to south, Anatolia to southern Arabia, incorporating modern-day Oman and Yemen. Its temporal coverage spans from the late eighth century BCE to the seventh century CE during the rise of Islam and collapse of the Sasanian Empire. The authors argue that the persistence of large states and empires starting in the eighth/ seventh centuries BCE, which continued for many centuries, led to new socio-political structures and institutions emerging in the Near East. The primary processes that enabled this emergence were large-scale and long-distance movements, or population migrations. These patterns of social developments are analysed under different aspects: settlement patterns, urban structure, material culture, trade, governance, language spread and religion, all pointing at population movement as the main catalyst for social change. This book’s argument Mark Altaweel is framed within a larger theoretical framework termed as ‘universalism’, a theory that explains WORLD A many of the social transformations that happened to societies in the Near East, starting from Andrea Squitieri the Neo-Assyrian period and continuing for centuries. Among other infl uences, the effects of these transformations are today manifested in modern languages, concepts of government, universal religions and monetized and globalized economies. -

Problems and Innovations

ТЕХНИЧЕСКИЕ НАУКИ........................................................................................................... 7 О СОВЕРШЕНСТВОВАНИИ ТЕХНОЛОГИИ ЗАГОТОВКИ ДРЕВЕСИНЫ ОСИНЫ КАК МАТЕРИАЛА ДЛЯ УСТРОЙСТВА КРОВЛИ С УЧЕТОМ ПРИРОДНЫХ И ПРОИЗВОДСТВЕННЫХ УСЛОВИЙ БОРИСОВ А.Ю., КОЛЕСНИКОВ Г.Н. ...................................................................................... 8 АНАЛИЗ УЯЗВИМОСТЕЙ ИСХОДНОГО КОДА НА ЭТАПАХ РАЗРАБОТКИ ПРОГРАММНОГО ОБЕСПЕЧЕНИЯ НЕСТЕРЕНКО М.А. МИКОВА С.А., БЕЛОЗЁРОВА А.А. ...................................................... 14 СХЕМА МОБИЛЬНОЙ СИСТЕМЫ КРУГОВОГО ОБЗОРА ДЛЯ ВИДЕОСКАНИРОВАНИЯ ПРОСТРАНСТВА СМИРНОВ М.Л. ...................................................................................................................... 20 СЕЛЬСКОХОЗЯЙСТВЕННЫЕ НАУКИ ................................................................................ 24 УРОЖАЙНОСТЬ ОДНОЛЕТНИХ ТРАВ ПО СИСТЕМАМ ОСНОВНОЙ ОБРАБОТКИ ПОЧВЫ В СЕВЕРНОМ ЗАУРАЛЬЕ РЗАЕВА В.В. .......................................................................................................................... 25 ЭКОНОМИЧЕСКИЕ НАУКИ .................................................................................................. 30 НЕЙРО-СЕТЕВАЯ ТРАНСФОРМАЦИЯ СТРУКТУРЫ ИНФОРМАЦИОННОЙ ЭКОНОМИКИ ДЯТЛОВ С.А. .......................................................................................................................... 31 МЕЖДИСЦИПЛИНАРНЫЙ ПОДХОД К ИССЛЕДОВАНИЮ НЕЙРО-СЕТЕВОЙ РЕИНДУСТРИАЛИЗАЦИИ ЭКОНОМИКИ ДЯТЛОВ С.А., НОВОСЕЛОВА Е.М. ..................................................................................... -

119 Original Article the GOLDEN SHRINES of TUTANKHAMUN

id9070281 pdfMachine by Broadgun Software - a great PDF writer! - a great PDF creator! - http://www.pdfmachine.com http://www.broadgun.com Egyptian Journal of Archaeological and Restoration Studies "EJARS" An International peer-reviewed journal published bi-annually Volume 2, Issue 2, December - 2012: pp: 119-130 www. ejars.sohag-univ.edu.eg Original article THE GOLDEN SHRINES OF TUTANKHAMUN AND THEIR INTENDED BURIAL PLACE Soliman, R. Lecturer, Tourism guidance dept., Faculty of Archaeology & Tourism guidance, Misr Univ. for Sciences & Technology, 6th October city, Egypt E-mail: [email protected] Received 3/5/2012 Accepted 12/10/2012 Abstract The most famous tomb at the Valley of the Kings, KV 62 housed so far the most intact discovery of royal funerary treasures belonging to the eighteenth dynasty boy-king Tutankhamun. The tomb has a simple architectural plan clearly prepared for a non- royal burial. However, the hastily death of Tutankhamun at a young age caused his interment in such unusually small tomb. The treasures discovered were immense in number, art finesse and especially in the amount of gold used. Of these treasures the largest shrine of four shrines laid in the burial chamber needed to be dismantled and reassembled in the tomb because of its immense size. Clearly the black marks on this shrine helped in the assembly and especially the orientation in relation to the burial chamber. These marks are totally incorrect and prove that Tutankhamun was definitely intended to be buried in another tomb. Keywords: KV62, WV23, Golden shrines, Tutankhamun, Burial chamber, Orientation. 1. Introduction Tutankhamun was only nine and the real cause of his death remains years old when he got to throne; at that enigmatic. -

A History of the World in 100 Objects Free

FREE A HISTORY OF THE WORLD IN 100 OBJECTS PDF Neil MacGregor | 640 pages | 01 Dec 2012 | Penguin Books Ltd | 9780241951774 | English | London, United Kingdom A History Of The World In Objects pdf Free Download - We use cookies to make our website work more efficiently, to provide you with more personalised services or advertising to you, and to analyse traffic on our website. For more information on how we use cookies and how to manage cookies, please follow the 'Read more' link, otherwise select 'Accept and close'. Please note only certain galleries on the Lower and Ground floors A History of the World in 100 Objects open to visitors. Our trails will take you on fascinating tours, highlighting the most popular objects on display and covering a variety of themes. Skip to main content Please enable JavaScript in your web browser to get the best experience. Read more about our cookie policy Accept and close the cookie policy. Object trails. The Royal Game of Ur on Collection online. You are in the Visit section Home Visit Object trails. Share the page Share on Facebook Share on Twitter. Visiting information Plan your visit. View the Museum map. Choose from a selection of object trails around the Museum. One hour at the Museum This trail will take you on a whirlwind tour of the history of the world. Collecting and empire trail Learn how colonial relationships shaped the British Museum's collection. Twelve objects to see with children From ancient armour to mummies, travel back in time on this captivating trail. Three hours at the A History of the World in 100 Objects This three-hour trail showcases the most popular objects on display. -

![Beloved of Amun-Ra, Lord of the Thrones of Two-Lands Who Dwells in Pure-Mountain [I.E., Gebel Barkal]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5688/beloved-of-amun-ra-lord-of-the-thrones-of-two-lands-who-dwells-in-pure-mountain-i-e-gebel-barkal-1475688.webp)

Beloved of Amun-Ra, Lord of the Thrones of Two-Lands Who Dwells in Pure-Mountain [I.E., Gebel Barkal]

1 2 “What is important for a given people is not the fact of being able to claim for itself a more or less grandiose historic past, but rather only of being inhabited by this feeling of continuity of historic consciousness.” - Professor Cheikh Anta DIOP Civilisation ou barbarie, pg. 273 3 4 BELOVED OF AMUN-RA A colossal head of Ramesses II (r. 1279-1213 BCE) is shifted by native workers in the Ramesseum THE LOST ORIGINS OF THE ANCIENT NAMES OF THE KINGS OF RWANDA STEWART ADDINGTON SAINT-DAVID © 2019 S. A. Saint-David All rights reserved. 5 A stele of King Harsiotef of Meroë (r. 404-369 BCE),a Kushite devotee of the cult of Amun-Ra, who took on a full set of titles based on those of the Egyptian pharaohs Thirty-fifth regnal year, second month of Winter, 13th day, under the majesty of “Mighty-bull, Who-appears-in-Napata,” “Who-seeks-the-counsel-of-the-gods,” “Subduer, 'Given'-all-the-desert-lands,” “Beloved-son-of-Amun,” Son-of-Ra, Lord of Two-Lands [Egypt], Lord of Appearances, Lord of Performing Rituals, son of Ra of his body, whom he loves, “Horus-son-of-his-father” [i.e., Harsiotef], may he live forever, Beloved of Amun-Ra, lord of the Thrones of Two-Lands Who dwells in Pure-Mountain [i.e., Gebel Barkal]. We [the gods] have given him all life, stability, and dominion, and all health, and all happiness, like Ra, forever. Behold! Amun of Napata, my good father, gave me the land of Nubia from the moment I desired the crown, and his eye looked favorably on me. -

Eine Geschichte Der Welt in 100 Objekten

EineNeil MacGregor Geschichte der Welt in 100 Objekten 2 3 Aus dem Englischen von Waltraud Götting, CD 4 Laufzeit ca. 71 Minuten CD 7 Laufzeit ca. 67 Minuten Andreas Wirthensohn und Annabel Zettel 1 Die Anfänge von Wissenschaft 1 Reichsgründer (300 v. Chr.–10 n. Chr.) Gelesen von Hanns Zischler, Rahel Comtesse, und Literatur (2000–700 v. Chr.) 2 Münze mit dem Kopf des Alexander Detlef Kügow und Nico Holonics 2 Die Sintflut-Tafel 3 Ashoka-Säule Redaktion und Regie: Antonio Pellegrino 3 Rhind-Papyrus zur Mathematik 4 Der Stein von Rosette Regieassistenz: Kirsten Böttcher 4 Minoischer Stierspringer 5 Lackierte chinesische Tasse Sound-Design: Dagmar Petrus und Christoph Brandner 5 Der goldene Schulterkragen aus Mold aus der Han-Zeit Studioaufnahmen, Schnitt, Sound-Mix: Ruth-Maria Ostermann 6 Statue von Ramses II. 6 Kopf des Augustus Produktion: Bayerischer Rundfunk/Der Hörverlag 2012 CD 5 Laufzeit ca. 59 Minuten CD 8 Laufzeit ca. 65 Minuten 1 Alte Welt, neue Mächte 1 Antike Freuden, modernes Gewürz (1100–300 v. Chr.) (1–500 n. Chr.) 2 Das Lachisch-Relief 2 Warren Cup CD 1 Laufzeit ca. 60 Minuten 3 Die Liebenden von Ain Sakhri 3 Die Sphinx des Taharqa 3 Nordamerikanische Otterpfeife 1 Wie wir Menschen wurden 4 Ägyptisches Tonmodell von Rindern 4 Chinesisches Ritualgefäß 4 Gürtel für ein rituelles Ballspiel (2 000 000–9000 v. Chr.) 5 Maya-Statue des Maisgottes aus der Zhou-Zeit 5 Ermahnungs-Bildrolle 2 Die Mumie des Hornedjitef 6 Topf der J mon-Kultur 5 Textil der Paracas-Kultur 6 Pfefferstreuer von Hoxne 3 Steinernes Schneidewerkzeug der 6 Die Goldmünze des Krösus Oldowan-Kultur CD 3 Laufzeit ca. -

Yale Egyptological Studies 7 the Inscription of Queen Katimala At

Yale Egyptological Studies 7 The Inscription of Queen Katimala at Semna: Textual Evidence for the Origins of the Napatan State Yale Egyptological Studies CHIEF EDITOR John Coleman Darnell EDITORS Hans-Werner Fischer-Elfert Bentley Layton ESTABLISHED BY William Kelly Simpson Yale Egyptological Studies 7 The Inscription of Queen Katimala at Semna Textual Evidence for the Origins of the Napatan State John Coleman Darnell Yale Egyptological Studies 7 ISBN 0-9740025-3-4 © 2006 Yale Egyptological Seminar All Rights Reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in an information retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper. Contents Editor’s Preface vii Preface ix List of Illustrations xi Introduction—Katimala’s Tableau and Semna 1 The Scene and Annotations 7 The Main Inscription 17 Part 1: Introduction—the complaint of a ruler to Katimala 17 Part 2: The Queen Responds 26 Part 3: The Queen Addresses a Council of Chiefs—Fear is the Enemy 31 Part 4: The Queen Addresses a Council of Chiefs— What is Good and What is Bad 36 Part 5: The Queen Addresses a Council of Chiefs— Make Unto Amun a New Land 39 Part 6: The Queen Addresses a Council of Chiefs—The Cattle of Amun 40 Part 7: The Fragmentary Conclusion 44 Dating the Inscription—Palaeography and Grammar 45 Literary Form and a Theory of Kingship 49 An Essay at Historical Interpretation 55 The Main Inscription—Continuous Transliteration and Translation 65 Bibliography 73 Glossary 93 Grammatical Index 99 Index 101 Plates 103 v Editor’s Preface This seventh volume of the Yale Egyptological Studies marks a change in the scope of the series. -

DSFRA IKEN Report Template

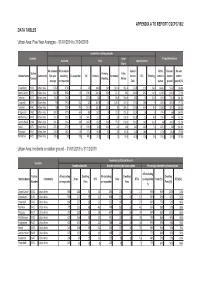

APPENDIX A TO REPORT CSCPC/19/2 DATA TABLES Urban Area: Five-Year Averages – 01/04/2014 to 31/04/2019 Incidents on station grounds Location False Pump Attendances Overview Fires Special Service Alarm All incidents All incidents Special All by On own On own Station Primary: False Station Name Community five-year excluding Co-responder All Primary Secondary Service RTC Flooding station's station station Number Dwelling Alarms average co-responder Calls pumps ground ground (%) Greenbank KV50 Urban Area 878.6 878.6 0 245 104.6 56.6 140.4 361.4 271.8 21.6 24.6 1424.8 974.2 68.4% Danes Castle KV32 Urban Area 832.6 830.8 1.8 198.8 126.4 56.6 72.4 385 248.4 29.2 14.8 1090.6 849.4 77.9% Torquay KV17 Urban Area 744.8 744.8 0 207.8 111 59 96.8 306.8 230 36 15.8 919.8 776.4 84.4% Crownhill KV49 Urban Area 742 741.8 0.2 227 100.6 43 126.4 337.4 177.4 28.6 9 878.4 680.6 77.5% Taunton KV61 Urban Area 734 733.4 0.6 227.8 132.8 56.6 95 284.6 221.6 65.4 8.4 1038.8 901.8 86.8% Bridgwater KV62 Urban Area 584.2 577.6 6.6 160 88.2 38 71.8 231.8 192.4 56 8 774.4 666 86.0% Middlemoor KV59 Urban Area 537.6 535.8 1.8 144.2 91.2 33 53 239.6 153.8 51 8.8 724.4 444 61.3% Camels Head KV48 Urban Area 491.6 491.2 0.4 162.8 85.2 50.4 77.6 178.6 150.2 16.6 11.8 638 390.2 61.2% Yeovil KV73 Urban Area 471.6 471.6 0 139.6 78.6 34.8 61 191 141 46.8 7.4 674.2 569 84.4% Plympton KV47 Urban Area 218.4 204.4 14 57.8 34.8 12 23 87.8 72.4 18.6 3 170.6 135.8 79.6% Plymstock KV51 Urban Area 185.8 185 0.8 48.4 27.4 12 21 76.8 60.6 12.6 2.6 165.4 123.8 74.8% Urban Area: Incidents on -

Decoding the Medinet Habu Inscriptions: the Ideological Subtext of Ramesses III’S War Accounts

Peters 1 Decoding the Medinet Habu Inscriptions: The Ideological Subtext of Ramesses III’s War Accounts Abstract: The temple of Medinet Habu in Thebes stands as Ramesses III‘s lasting legacy to Ancient Egyptian history. This monumental structure not only contained luxury goods within, but also a goldmine of information inscribed on its outside walls. Here, Ramesses adorned the temple with stories of military campaigns he led against enemies in the north who hoped to gain control of Egypt. These war accounts have posed a series of problems to modern scholars. Today, the debate still rages over how the inscriptions should be interpreted. This work analyzes Ramesses‘s records through the lens of socioeconomic decline that occurred during his rule in order to demonstrate the role ideology—namely ma‘at—played in his self-representation and his methodology to ensure and legitimize his rule during these precarious times. Scott M. Peters Senior Thesis, Department of History Columbia College, Columbia University April 2011 Advisors: Professor Marc Van De Mieroop and Professor Martha Howell Word Count: 17,070 (with footnotes + bibliography included) Peters 2 Figure 1: Map of Ancient Egypt with key sites. Image reproduced from Marc Van De Mieroop, A History of Ancient Egypt (Malden: Wiley-Blackwell, 2011), 28. Peters 3 Introduction When describing his victory over invading forces in the north of Egypt, Ramesses III, ruler at the time, wrote: …Those who came on land were overthrown and slaughtered…Amon-Re was after them destroying them. Those who entered the river mouths were like birds ensnared in the net…their leaders were carried off and slain. -

Illuminating the Path of Darkness

ILLUMINATING THE PATH OF DARKNESS: Social and sacred power of artificial light in Pharaonic Period Egypt This thesis is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Meghan E. Strong Girton College University of Cambridge January 2018 Illuminating the path of darkness: social and sacred power of artificial light in Pharaonic Period Egypt Meghan E. Strong ABSTRACT Light is seldom addressed in archaeological research, despite the fact that, at least in ancient Egypt, it would have impacted upon all aspects of life. When discussing light in Egyptology, the vast majority of scholarly attention is placed on the sun, the primary source of illumination. In comparison, artificial light receives very little attention, primarily due to a lack of archaeological evidence for lighting equipment prior to the 7th century BC. However, 19th and 20th century lychnological studies have exaggerated this point by placing an overwhelming emphasis on decorated lamps from the Greco-Roman Period. In an attempt to move beyond these antiquarian roots, recent scholarship has turned towards examining the role that light, both natural and artificial, played in aspects of ancient societies’ architecture, ideology and religion. The extensive body of archaeological, textual and iconographic evidence that remains from ancient Egypt is well suited to this type of study and forms three core data sets in this thesis. Combining a materials- based examination of artificial light with a contextualized, theoretical analysis contributes to a richer understanding of ancient Egyptian culture from the 3rd to 1st millennium BC. The first three chapters of this study establish a typology of known artificial lighting equipment, as well as a lexicon of lighting terminology.