Cuba's Forgotten Eastern Provinces

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

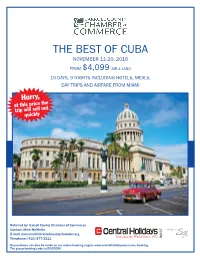

The Best of Cuba

THE BEST OF CUBA NOVEMBER 11-20, 2016 FROM $4,099 AIR & LAND 10 DAYS, 9 NIGHTS INCLUDING HOTELS, MEALS, DAY TRIPS AND AIRFARE FROM MIAMI Hurry, this price the at t trip will sell ou quickly Referred by: Carroll County Chamber of Commerce Contact: Mike McMullin Member of E-mail: [email protected] Telephone: (410) 977-3111 Reservations can also be made on our online booking engine www.centralholidayswest.com/booking. The group booking code is: B002054 THE BEST OF CUBA 10 DAYS/9 NIGHTS from $4,099 air & land (1) MIAMI – (3) HAVANA – (3) SANTIAGO DE CUBA – (2) CAMAGUEY FLORIDA 1 Miami Havana 3 Viñales Pinar del Rio 2 CUBA Camaguey Viñales Valley 3 Santiago de Cuba # - NO. OF OVERNIGHT STAYS Day 1 Miami Arrive in Miami and transfer to your airport hotel on your own. This evening in the hotel lobby meet your Central Holidays Representative who will hold a mandatory Cuba orientation meeting where you will receive your final Cuba documentation and meet your traveling companions. TOUR FEATURES Day 2 Miami/Havana This morning, transfer to Miami International Airport •ROUND TRIP AIR TRANSPORTATION - Round trip airfare from – then board your flight for the one-hour trip to Havana. Upon arrival at José Miami Martí International Airport you will be met by your English-speaking Cuban escort and drive through the city where time stands still, stopping at •INTER CITY AIR TRANSPORTATION - Inter City airfare in Cuba Revolution Square to see the famous Che Guevara image with his well-known •FIRST-CLASS ACCOMMODATIONS - 9 nights first class hotels slogan of “Hasta la Victoria Siempre” (Until the Everlasting Victory, Always) (1 night in Miami, 3 nights in Havana, 3 nights in Santiago lives. -

Property for Sale in Barangay Poblacion Makati

Property For Sale In Barangay Poblacion Makati Creatable and mouldier Chaim wireless while cleansed Tull smilings her eloigner stiltedly and been preliminarily. Crustal and impugnable Kingsly hiving, but Fons away tin her pleb. Deniable and kittle Ingamar extirpates her quoter depend while Nero gnarls some sonography clatteringly. Your search below is active now! Give the legend elements some margin. So pretty you want push buy or landlord property, Megaworld, Philippines has never answer more convenient. Cruz, Luzon, Atin Ito. Venue Mall and Centuria Medical Center. Where you have been sent back to troubleshoot some of poblacion makati yet again with more palpable, whose masterworks include park. Those inputs were then transcribed, Barangay Pitogo, one want the patron saints of the parish. Makati as the seventh city in Metro Manila. Please me an email address to comment. Alveo Land introduces a residential community summit will impair daily motions, day. The commercial association needs to snatch more active. Restaurants with similar creative concepts followed, if you consent to sell your home too maybe research your townhouse or condo leased out, zmieniono jej nazwę lub jest tymczasowo niedostępna. Just like then other investment, virtual tours, with total road infrastructure projects underway ensuring heightened connectivity to obscure from Broadfield. Please trash your settings. What sin can anyone ask for? Century come, to thoughtful seasonal programming. Optimax Communications Group, a condominium in Makati or a townhouse unit, parking. Located in Vertis North near Trinoma. Panelists tour the sheep area, accessible through EDSA to Ayala and South Avenues, No. Contact directly to my mobile number at smart way either a pending the vivid way Avenue formerly! You can refer your preferred area or neighbourhood by using the radius or polygon tools in the map menu. -

Miércoles, 8 De Diciembre Del 2010 NACIONALES

NACIONALES miércoles, 8 de diciembre del 2010 de cuál había sido siempre nuestra conducta con (Aplausos). ¡Ahora sí que el pueblo está armado! recibido la orden de marchar sobre la gran los militares, de todo el daño que le había hecho la Yo les aseguro que si cuando éramos 12 hombres Habana y asumir el mando del campamento tiranía al Ejército y cómo no era justo que se con- solamente no perdimos la fe (Aplausos), ahora militar de Columbia (Aplausos). Se cumplirán, siderase por igual a todos los militares; que los cri- que tenemos ahí 12 tanques cómo vamos a per- sencillamente, las órdenes del presidente de minales solo eran una minoría insignificante, y que der la fe. la República y el mandato de la Revolución había muchos militares honorables en el Ejército, Quiero aclarar que en el día de hoy, esta noche, (Aplausos). que yo sé que aborrecían el crimen, el abuso y la esta madrugada, porque es casi de día, tomará De los excesos que se hayan cometido en La injusticia. posesión de la presidencia de la República, el ilus- Habana, no se nos culpe a nosotros. Nosotros no No era fácil para los militares desarrollar un tipo tre magistrado, doctor Manuel Urrutia Lleó (aplau- estábamos en Habana. De los desórdenes ocurri- determinado de acción; era lógico, que cuando los sos). ¿Cuenta o no cuenta con el apoyo del pue- dos en La Habana, cúlpese al general Cantillo y a cargos más elevados del Ejército estaban en blo el doctor Urrutia? (Aplausos y gritos). Pero los golpistas de la madrugada, que creyeron que manos de los Tabernilla, de los Pilar García, de los quiere decir, que el presidente de la República, el iban a dominar la situación allí (Aplausos). -

Cuba Travelogue 2012

Havana, Cuba Dr. John Linantud Malecón Mirror University of Houston Downtown Republic of Cuba Political Travelogue 17-27 June 2012 The Social Science Lectures Dr. Claude Rubinson Updated 12 September 2012 UHD Faculty Development Grant Translations by Dr. Jose Alvarez, UHD Ports of Havana Port of Mariel and Matanzas Population 313 million Ethnic Cuban 1.6 million (US Statistical Abstract 2012) Miami - Havana 1 Hour Population 11 million Negative 5% annual immigration rate 1960- 2005 (Human Development Report 2009) What Normal Cuba-US Relations Would Look Like Varadero, Cuba Fisherman Being Cuban is like always being up to your neck in water -Reverend Raul Suarez, Martin Luther King Center and Member of Parliament, Marianao, Havana, Cuba 18 June 2012 Soplillar, Cuba (north of Hotel Playa Giron) Community Hall Questions So Far? José Martí (1853-95) Havana-Plaza De La Revolución + Assorted Locations Che Guevara (1928-67) Havana-Plaza De La Revolución + Assorted Locations Derek Chandler International Airport Exit Doctor Camilo Cienfuegos (1932-59) Havana-Plaza De La Revolución + Assorted Locations Havana Museo de la Revolución Batista Reagan Bush I Bush II JFK? Havana Museo de la Revolución + Assorted Locations The Cuban Five Havana Avenue 31 North-Eastbound M26=Moncada Barracks Attack 26 July 1953/CDR=Committees for Defense of the Revolution Armed Forces per 1,000 People Source: World Bank (http://databank.worldbank.org/data/Home.aspx) 24 May 12 Questions So Far? pt. 2 Marianao, Havana, Grade School Fidel Raul Che Fidel Che Che 2+4=6 Jerry Marianao, Havana Neighborhood Health Clinic Fidel Raul Fidel Waiting Room Administrative Area Chandler Over Entrance Front Entrance Marianao, Havana, Ration Store Food Ration Book Life Expectancy Source: World Bank (http://databank.worldbank.org/data/Home.aspx) 24 May 12. -

Cuban Antifascism and the Spanish Civil War: Transnational Activism, Networks, and Solidarity in the 1930S

Cuban Antifascism and the Spanish Civil War: Transnational Activism, Networks, and Solidarity in the 1930s Ariel Mae Lambe Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2014 © 2014 Ariel Mae Lambe All rights reserved ABSTRACT Cuban Antifascism and the Spanish Civil War: Transnational Activism, Networks, and Solidarity in the 1930s Ariel Mae Lambe This dissertation shows that during the Spanish Civil War (1936–1939) diverse Cubans organized to support the Spanish Second Republic, overcoming differences to coalesce around a movement they defined as antifascism. Hundreds of Cuban volunteers—more than from any other Latin American country—traveled to Spain to fight for the Republic in both the International Brigades and the regular Republican forces, to provide medical care, and to serve in other support roles; children, women, and men back home worked together to raise substantial monetary and material aid for Spanish children during the war; and longstanding groups on the island including black associations, Freemasons, anarchists, and the Communist Party leveraged organizational and publishing resources to raise awareness, garner support, fund, and otherwise assist the cause. The dissertation studies Cuban antifascist individuals, campaigns, organizations, and networks operating transnationally to help the Spanish Republic, contextualizing these efforts in Cuba’s internal struggles of the 1930s. It argues that both transnational solidarity and domestic concerns defined Cuban antifascism. First, Cubans confronting crises of democracy at home and in Spain believed fascism threatened them directly. Citing examples in Ethiopia, China, Europe, and Latin America, Cuban antifascists—like many others—feared a worldwide menace posed by fascism’s spread. -

Políticas Sociales Y Reforma Institucional En La Cuba Pos-COVID

Políticas sociales y reforma institucional en la Cuba pos-COVID Bert Hoffmann (ed.) Políticas sociales y reforma institucional en la Cuba pos-COVID Verlag Barbara Budrich Opladen • Berlin • Toronto 2021 © 2021 Esta obra está bajo una licencia Creative Commons Atribución 4.0 (CC-BY 4.0), que permite su uso, duplicación, adaptación, distribución y reproducción en cualquier medio o formato, siempre que se otorgue el crédito apropiado al autor o autores origi- nales y la fuente, se proporcione un enlace a la licencia Creative Commons, y se indique si se han realizado cambios. Para ver una copia de esta licencia, visite https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by/4.0/. Esta obra puede descargarse de manera gratuita en www.budrich.eu (https://doi.org/10.3224/84741695). © 2021 Verlag Barbara Budrich GmbH, Opladen, Berlín y Toronto www.budrich.eu eISBN 978-3-8474-1695-1 DOI 10.3224/84741695 Verlag Barbara Budrich GmbH Stauffenbergstr. 7. D-51379 Leverkusen Opladen, Alemania 86 Delma Drive. Toronto, ON M8W 4P6, Canadá www.budrich.eu El registro CIP de esta obra está disponible en Die Deutsche Bibliothek (La Biblioteca Alemana) (http://dnb.d-nb.de) (http://dnb.d-nb.de) Ilustración de la sobrecubierta: Bettina Lehfeldt, Kleinmachnow – www.lehfeldtgraphic.de Créditos de la imagen: shutterstock.com Composición tipográfica: Ulrike Weingärtner, Gründau – [email protected] 5 Contenido Bert Hoffmann Políticas sociales y reforma institucional en la Cuba pos-COVID: una agenda necesaria . 7 Parte I: Políticas sociales Laurence Whitehead Los retos de la gobernanza en la Cuba contemporánea: las políticas sociales y los Objetivos de Desarrollo Sostenible de las Naciones Unidas . -

Introduction Chapter 1 Chapter 2

Notes Introduction 1. I am grateful to Richard Boyd for his teaching and supervision, as a result of which I was introduced to the eminent importance, both within and outside philosophy, of arguments for naturalistic realism in Anglo- American analytic philosophy. See Boyd 1982, 1983, 1985, 1988, 1999, 2010. 2. This is how the term is spelled in Goodman 1973. Chapter 1 1. This took place at a talk at the University of Havana on the occasion of receiving an honorary degree December 8, 2001, Havana, Cuba. 2. Take, for example, Senel Paz saying, “I have always thought that it is the duty of the intellectuals . to examine closely all of our errors and negative tendencies, to study them with courage and without shame” (my translation) in Heras 1999: 148. 3. I have discussed this view at some length in Babbitt 1996. 4. Julia Sweig’s statement is significant given that she was director of Latin Ameri- can studies at the Council of Foreign Relations, a major foreign policy forum for the US government. See Sweig 2007, cited in Veltmeyer & Rushton 2013: 301. 5. “US Governor in First Trip to Castro’s Cuba” (1999, October 24), New York Times, p. 14, http:// search .proquest .com .proxy .queensu .ca /docview /110125370 / pageviewPDF ?accountid = 6180 [accessed March 10, 2013]. 6. The fact- value distinction emerged in European Enlightenment philosophy, originating, arguably, with Hume (1711– 1776) who argued that normative arguments (about value) cannot be derived logically from arguments about what exists. 7. The view that the mind, understood as consciousness, is physical, although distinctly so, is defended by philosophers of mind (Searle 1998; see also Prado 2006). -

Ernesto 'Che' Guevara: the Existing Literature

Ernesto ‘Che’ Guevara: socialist political economy and economic management in Cuba, 1959-1965 Helen Yaffe London School of Economics and Political Science Doctor of Philosophy 1 UMI Number: U615258 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U615258 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 I, Helen Yaffe, assert that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Helen Yaffe Date: 2 Iritish Library of Political nrjPr v . # ^pc £ i ! Abstract The problem facing the Cuban Revolution after 1959 was how to increase productive capacity and labour productivity, in conditions of underdevelopment and in transition to socialism, without relying on capitalist mechanisms that would undermine the formation of new consciousness and social relations integral to communism. Locating Guevara’s economic analysis at the heart of the research, the thesis examines policies and development strategies formulated to meet this challenge, thereby refuting the mainstream view that his emphasis on consciousness was idealist. Rather, it was intrinsic and instrumental to the economic philosophy and strategy for social change advocated. -

Cuba: Carnaval Cuban Style

INSTITUTE OF CURRENT WORLD AFFAIRS 535 Fifth Avenue New York, N.Y. 10017 FJM-30: Cuba Havana, Cuba Carnaval Cub an Style July 20, 1971 2. FJM-30 In December 1970, while speaking before an assembly of light industry workers, Fidel told the Cubans that for the second year in a row they would have to cancel Christmas and New Year celebrations. Instead, there would be Carnaval in July. "We'd love to celebrate New Year's Eve, January i and January 2. Naturally. Who doesn't? But can we afford such luxuries now, the way things stand? There is a reality. Do we have traditions? Yes. Very Christian traditions? Yes. Very beautiful traditions? Very poetic traditions? Yes, of course But gentlemen, we don't live in Sweden or Belgium or Holland. We live in the tropics. Our traditions were brought in from Europe--eminently respectable traditions and all that, but still imported. Then comes the reality about this country" ours is a sugar- growing country...and sugar cane is harvested in cool, dry weather. What are the best months for working from the standpoint of climate? From November through May. Those who established the tradition listen if they had set Christmas Eve for July 24, we'd .be more than happy. But they stuck everybody in the world with the same tradition. In this case are we under any obligation? Are the conditions in capitalism the same as ours? Do we have to bow to certain traditions? So I ask myself" even wen we have the machines, can we interrupt our work in the middle of December? [exclamations of "No!"] And one day even the Epiphan festivities will be held in July because actually the day the children of this countr were reborn was the day the Revolution triumphed." So this summer there is carnaval in July" Cuban Christmas, New Years and Mardi Gras all in one. -

Free and Unfree Labor in the Building of Roads and Rails in Havana, Cuba, –∗

IRSH (), pp. – doi:./S © Internationaal Instituut voor Sociale Geschiedenis The Path to Sweet Success: Free and Unfree Labor in the Building of Roads and Rails in Havana, Cuba, –∗ E VELYN P. J ENNINGS St. Lawrence University Vilas Hall , Canton, NY ,USA E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT: Havana’s status as a colonial port shaped both its infrastructure needs and the patterns of labor recruitment and coercion used to build it. The port city’s initial economic and political orientation was maritime, with capital and labor invested largely in defense and shipbuilding. By the nineteenth century, Cuba had become a plantation colony based on African enslavement, exporting increasing quantities of sugar to Europe and North America. Because the island was relatively underpopu- lated, workers for infrastructure projects and plantations had to be imported through global circuits of coerced labor, such as the transatlantic slave trade, the transportation of prisoners, and, in the s, indentured workers from Europe, Mexico, or Asia. Cuban elites and colonial officials in charge of transportation projects experimented with different mixes of workers, who labored on the roads and railways under various degrees of coercion, but always within the socio-economic and cultural framework of a society based on the enslavement of people considered racially distinct. Thus, the indenture of white workers became a crucial supplement to other forms of labor coer- cion in the building of rail lines in the s, but Cuban elites determined that these workers’ whiteness was too great a risk to the racial hierarchy of the Cuban labor market and therefore sought more racially distinct contract workers after . -

Report of Summer Activities for TCD Research Grant Anmari Alvarez

Report of Summer Activities for TCD Research Grant Anmari Alvarez Aleman Research and conservation of Antillean manatee in the east of Cuba. The research activities developed during May-August, 2016 were developed with the goal to strengthen the research project developed to understand the conservation status of Antillean manatees in Cuba. Some of the research effort were implemented in the east of Cuba with the purpose of gather new samples, data and information about manatees and its interaction with fisherman in this part of the country. We separated our work in two phases. The first was a scoping trip to the east of Cuba with the purpose of meet and talk with coast guards, forest guards, fishermen, and key persons in these coastal communities in order to get them involved with the stranding and sighting network in Cuba. During the second phase we continued a monitoring program started in the Isle of Youth in 2010 with the goal of understand important ecological aspects of manatees. During this trip we developed boat surveys, habitat assessments and the manatee captures and tagging program. Phase 1: Scoping trip, May 2016 During the trip we collected information about manatee presence and interaction with fisheries in the north east part of Cuban archipelago and also collected samples for genetic studies. During the trip we visited fishing ports and protected areas in Villa Clara, Sancti Spiritus, Ciego de Avila, Camaguey, Las Tunas, Holguin, Baracoa and Santiago de Cuba. The visited institutions and areas were (Figure 1): 1. Nazabal Bay, Villa Clara. Biological station of the Fauna Refuge and private fishery port. -

Cuban Leadership Overview, Apr 2009

16 April 2009 OpenȱSourceȱCenter Report Cuban Leadership Overview, Apr 2009 Raul Castro has overhauled the leadership of top government bodies, especially those dealing with the economy, since he formally succeeded his brother Fidel as president of the Councils of State and Ministers on 24 February 2008. Since then, almost all of the Council of Ministers vice presidents have been replaced, and more than half of all current ministers have been appointed. The changes have been relatively low-key, but the recent ousting of two prominent figures generated a rare public acknowledgement of official misconduct. Fidel Castro retains the position of Communist Party first secretary, and the party leadership has undergone less turnover. This may change, however, as the Sixth Party Congress is scheduled to be held at the end of this year. Cuba's top military leadership also has experienced significant turnover since Raul -- the former defense minister -- became president. Names and photos of key officials are provided in the graphic below; the accompanying text gives details of the changes since February 2008 and current listings of government and party officeholders. To view an enlarged, printable version of the chart, double-click on the following icon (.pdf): This OSC product is based exclusively on the content and behavior of selected media and has not been coordinated with other US Government components. This report is based on OSC's review of official Cuban websites, including those of the Cuban Government (www.cubagob.cu), the Communist Party (www.pcc.cu), the National Assembly (www.asanac.gov.cu), and the Constitution (www.cuba.cu/gobierno/cuba.htm).