Integrated Mariculture: Asking the Right Questions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nutrition, Feeds and Feed Technology for Mariculture in India Vijayagopal P

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by CMFRI Digital Repository Course Manual Nutrition, Feeds and Feed Technology for Mariculture in India Vijayagopal P. [email protected] Central Marine Fisheries Research Institute, Kochi - 18 Mariculture of finfish on a commercial scale is non-existent in India. CMFRI, RGCA of MPEDA, CIBA are the Institutions promoting finfish mariculture with demonstrated seed production capabilities of Asian seabass (Lates calcarifer), cobia (Rachycentron canadum) and silver pompano (Trachynotus blochii). Seed production is not sufficient enough togo in for commercial scale investment. Requisite private investment has not flown into this segment of aquabusiness and Public Private Partnerships (PPP) are yet to take off. The scenario being this in the case of one (seed) of the two major inputs in this food production system, feeds and feeding, which is the other is the subject of elaboration here. Quality marine fish like king seer, pomfrets and tuna retails at more than Rs.400/- per kg in domestic markets. In metro cities it Rs.1000/- per kg is not surprising. With this purchasing power in the domestic market, most of the farmed marine fish is sold to such a clientele which is ever increasing in India. Therefore, without any assurance of a sustainable supply of such fish from capture fisheries, there is no doubt that we have to farm quality marine fish. With as deficit in seed supply at present, let us examine nutrition, feeds and feed technology required for this farming system in India. Farming sites, technologies of cage fabrication and launch, day-to-day management, social issues, policy, economics and health management, harvest and marketing, development of value chains, traceability and certification are all equally important and may or may not be dealt with in this training programme. -

Can Sustainable Mariculture Match Agriculture's Output?

10/30/2018 Can sustainable mariculture match agriculture’s output? « Global Aquaculture Advocate ENVIRONMENTAL & SOCIAL RESPONSIBILITY (/ADVOCATE/CATEGORY/ENVIRONMENTAL-SOCIAL- RESPONSIBILITY) Can sustainable mariculture match agriculture’s output? Thursday, 18 August 2016 By Amir Neori, Ph.D. A global focus on macroalgae and marine plants will result in many jobs and increased food security A seaweed farmer in Nusa Lembongan gathers edible seaweed that has grown on a rope. Photo by Jean-Marie Hullot. https://www.aquaculturealliance.org/advocate/can-sustainable-mariculture-match-agricultures-output/?headlessPrint=AAAAAPIA9c8r7gs82oWZBA 10/30/2018 Can sustainable mariculture match agriculture’s output? « Global Aquaculture Advocate Currently, there is a signicant production difference between agriculture and aquaculture (an imbalance of around 100 to 1). Improving this relationship represents a signicant challenge to the aquaculture industry. A quantum leap in the scale of global food production is imperative to support increasing food needs on a global scale, as the human population continues to grow along with the additional demand for food. Climate change and its possible impacts on traditional food production practices must also be considered, and mariculture presents a unique opportunity. Agriculture produces about 10 billion tons annually of various products, most of which are plants. However, it is hard to imagine how this gure can grow much further, considering the toll of this production on diminishing resources of arable land, fertilizers and irrigation water. Strikingly, aquaculture production is a mere 1 percent of agriculture production, or about 100 million tons per year (according to FAO reports). This is astonishing in a world whose surface is 70 percent water, most of it an oceanic area that receives most of the world’s solar irradiation and that contains huge amounts of nutrients (e.g., 1011 tons of phosphorus), especially in the Pacic Ocean. -

Shrimp Farming in the Asia-Pacific: Environmental and Trade Issues and Regional Cooperation

Shrimp Farming in the Asia-Pacific: Environmental and Trade Issues and Regional Cooperation Recommended Citation J. Honculada Primavera, "Shrimp Farming in the Asia-Pacific: Environmental and Trade Issues and Regional Cooperation", trade and environment, September 25, 1994, https://nautilus.org/trade-an- -environment/shrimp-farming-in-the-asia-pacific-environmental-and-trade-issues-- nd-regional-cooperation-4/ J. Honculada Primavera Aquaculture Department Southeast Asian Fisheries Development Center Tigbauan, Iloilo, Philippines 5021 Tel 63-33-271009 Fax 63-33-271008 Presented at the Nautilus Institute Workshop on Trade and Environment in Asia-Pacific: Prospects for Regional Cooperation 23-25 September 1994 East-West Center, Honolulu Abstract Production of farmed shrimp has grown at the phenomenal rate of 20-30% per year in the last two decades. The leading shrimp producers are in the Asia-Pacific region while the major markets are in Japan, the U.S.A. and Europe. The dramatic failures of shrimp farms in Taiwan, Thailand, Indonesia and China within the last five years have raised concerns about the sustainability of shrimp aquaculture, in particular intensive farming. After a brief background on shrimp farming, this paper reviews its environmental impacts and recommends measures that can be undertaken on the farm, 1 country and regional levels to promote long-term sustainability of the industry. Among the environmental effects of shrimp culture are the loss of mangrove goods and services as a result of conversion, salinization of soil and water, discharge of effluents resulting in pollution of the pond system itself and receiving waters, and overuse or misuse of chemicals. Recommendations include the protection and restoration of mangrove habitats and wild shrimp stocks, management of pond effluents, regulation of chemical use and species introductions, and an integrated coastal area management approach. -

An Investigation of Impediments to Commercial Shellfish Mariculture in Virginia

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1990 An Investigation of Impediments to Commercial Shellfish Mariculture in Virginia Robert Charles Neikirk College of William and Mary - Virginia Institute of Marine Science Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the Fresh Water Studies Commons, and the Oceanography Commons Recommended Citation Neikirk, Robert Charles, "An Investigation of Impediments to Commercial Shellfish Mariculture in Virginia" (1990). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539617609. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.25773/v5-k2ra-fn95 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. AN INVESTIGATION OF IMPEDIMENTS TO COMMERCIAL SHELLFISH MARICULTURE IN VIRGINIA A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the School of Marine Science The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by ROBERT CHARLES NEIKIRK 1990 This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Approved August 1990 N. Bartlett Theberge, Jr., LL.M. Committee Chairman Carl H. Hobbs, III Walter I. Priest, III ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS . iv LIST OF TABLES. v ABSTRACT. vi INTRODUCTION. ... 2 LITERATURE REVIEW . 7 METHODS . 13 RESULTS ... 19 DISCUSSION . 28 Regulatory Impediments ....................................... 29 Impediments Associated with multiple use of the Coastal Zone . -

Mariculture and Food Production: Sustaining the Promise

POSITION PAPER 2012 MARICULTURE AND FOOD PRODUCTION SUSTAINING THE PROMISE Naveen Namboothri1,2, C.M. Muralidharan3 and Aarthi Sridhar1,4 1Dakshin Foundation, Bengaluru 2Centre for Ecological Studies, Indian Institute of Science, Bengaluru 3Consultant, Food and Agriculture Organization, Bangkok 4Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi Feeding the world with dwindling ranks second in world aquaculture production (see figure on stocks Pages 2-3), with an estimated production of 3,791,921 tonnes per annum. The origins of aquaculture date back more than 4,000 Marine fish stocks in many parts of the world years1. There is evidence that Egyptians cultured fish as early have been exploited beyond recovery, but this as 2500 BC2. The Chinese have a rich tradition of aquaculture has done little to slacken an increasing global practices that can be traced back to 2000 BC. Contemporary demand for sea food. These markets compel practices in this field are a result of the refinement and the producers throughout the world to fish out adaptation of these ancient experiments with aquaculture. even smaller sizes, effectively endangering reproducing populations of several commercial The tradition of aquaculture in India can be traced back to 300 species. Sustainability and equity in fisheries has BC, and certain practices involving the integration of paddy frequently been sacrificed in favour of meeting and fish farming techniques are seen in their more traditional this growing desire for seafood. Declining wild manifestations even today in Kerala and West Bengal. Even fish catch, increasing input costs of fishing though these traditional production methods were considered operations, and the unrelenting demand for low-technology, produced lesser quantities, and were often marine products has prompted an interest in low cost and less intensive, these traditional forms of fish aquaculture. -

Alaska Mariculture Development Plan

ALASKA MARICULTURE DEVELOPMENT PLAN STATE OF ALASKA MARCH 23, 2018 DRAFT Alaska Mariculture Development Plan // 1 Photo credit clockwise from top left: King crab juvenile by Celeste Leroux; bull kelp provided by Barnacle Foods; algae tanks in OceansAlaska shellfish hatchery provided by OceansAlaska; fertile blade of ribbon kelp provided by Hump Island Oyster Co.; spawning sea cucumber provided by SARDFA; icebergs in pristine Alaska waters provided by Alaska Seafood. Cover photos: Large photo: Bull kelp by ©“TheMarineDetective.com”. Small photos from left to right: Oyster spat ready for sale in a nursery FLUPSY by Cynthia Pring-Ham; juvenile king crab by Celeste Leroux; oyster and seaweed farm near Ketchikan, Alaska, provided by Hump Island Oyster Co. Back cover photos from left to right: Nick Mangini harvests kelp on Kodiak Island, by Trevor Sande; oysters on the half-shell, by Jakolof Bay Oyster Company; oyster spat which is set, by OceansAlaska. Photo bottom: “Mariculture – Made in Alaska” graphic provided by Alaska Dept. of Commerce, Community and Economic Development, Division of Economic Development Layout and design by Naomi Hagelund, Aleutian Pribilof Island Community Development Association (APICDA). This publication was created in part with support from the State of Alaska. This publication was funded in part by NOAA Award #NA14NMF4270058. The statements are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of NOAA or the U.S. Dept. of Commerce. 2 // Alaska Mariculture Development Plan TABLE OF CONTENTS Message from -

The Status of Mariculture in Northern China

271 The status of mariculture in northern China Chang Yaqing1 and Chen Jiaxin2 1Dalian Fisheries University Dalian, Liaoning, People’s Republic of China E-mail: [email protected] 2Yellow Sea Fisheries Research Institute Chinese Academy of Fisheries Sciences Qingdao, Shandong, People’s Republic of China Chang, Y. and Chen, J. 2008. The status of mariculture in northern China. In A. Lovatelli, M.J. Phillips, J.R. Arthur and K. Yamamoto (eds). FAO/NACA Regional Workshop on the Future of Mariculture: a Regional Approach for Responsible Development in the Asia- Pacific Region. Guangzhou, China, 7–11 March 2006. FAO Fisheries Proceedings. No. 11. Rome, FAO. 2008. pp. 271–284. INTRODUCTION The People’s Republic of China has a long history of mariculture production. The mariculture industry in China has achieved breakthroughs in the hatchery, nursery and culture techniques of shrimp, molluscs and fish of high commercial value since the 1950s. The first major development was seaweed culture during the 1950s, made possible by breakthroughs in breeding technology. By the end of the 1970s, annual seaweed production had reached 250 000 tonnes in dry weight (approximately 1.5 million tonnes of fresh seaweed). Shrimp culture developed during the 1980s because of advances in hatchery technology and economic reform policies. Annual shrimp production reached 210 000 tonnes in 1992. Disease outbreaks since 1993, however, have reduced shrimp production by about two-thirds. Mariculture production increased steadily between 1954 and 1985, but has been growing exponentially since 1986, mostly driven by mollusc culture. Mollusc culture in China began to expand beyond the four traditional species (oyster, cockle, razor clam and ruditapes clam) in the 1970s. -

Temporal Patterns of Adoption of Mariculture Innovation Globally

ARTICLES https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-019-0395-y Temporal patterns of adoption of mariculture innovation globally Rebecca R. Gentry *, Elizabeth O. Ruff and Sarah E. Lester Mariculture—farming seafood in the ocean—has been expanding in many countries and has the potential to be a critical compo- nent of a sustainable global food system. However, it has developed inconsistently across the globe, with minimal development in some regions, while in others intensive growth threatens sustainability. There is no overall understanding of trajectories of mariculture development around the world. We analyse mariculture development trends at the country level, drawing on dif- fusion of innovation theory. We show that most countries follow predictable patterns of development that are associated with key economic and governance indicators, such as regulatory quality. We also show that production of some taxa (for example, molluscs) is more strongly associated with stable production over time, as is growing a diversity of species. Taken together, our results suggest that enabling policies may unlock mariculture growth opportunities and that strategies that emphasize production of a diversity of species could contribute to a more stable mariculture industry. Further, by assessing each country’s trajectory of mariculture development in relation to its production potential, we consider the limits and opportunities for future mariculture growth and its contribution to sustainable food systems. ood production has notable and far-reaching effects, both Large-scale mariculture is relatively new in much of the world. positive and negative, on the health of people, society and the It requires shifts in livelihood strategies, expertise, infrastructure environment1. -

Social and Economic Impacts of Capture Fisheries and Mariculture

23 Social and Economic Impacts of Capture Fisheries and Mariculture Jacob Ochiewo Opposite page: Improvised fishmarket at landing site, Inhaca Island, Mozambique. © José Paula. INTRODUCTION that some species with a higher economic value (namely tuna, prawns and lobsters) are exported, and these species Several countries of the SW Indian Ocean are classified as are therefore scarce on local markets, or are prohibitively Least Developed Countries (LDC) by the UNDP, and expensive (FAO 2014). have a low Human Development Index (HDI) (UNDP Environmental degradation caused by fishing and 2014). High levels of poverty and rapid population growth mariculture activities (see Chapters 21 and 22) can reduce is pervasive, and in coastal communities along the main- potential harvests and food security, affect economic land (Mozambique, Tanzania, Kenya), Madagascar and on growth and reduce the quality of life in coastal communi- small islands (Comoros, Seychelles, Mauritius) capture ties. Domestic sewage and agricultural waste runoff, fisheries are integral to food security (see Chapter 21) and chemical contaminants and microbial run-off increase the the functioning of social and economic systems. In recent risk of disease (see references in European Marine Board years, mariculture initiatives have taken root in some areas, 2013). Food safety systems for fish products, such as such as seaweed farming in Zanzibar, but at a regional scale Standard Sanitary Operation Processes (SSOP) and Haz- it is still in an early developmental phase (see Chapter 22). ard Analysis Critical Control Point (HACCP) programmes Fish is rich in essential nutrients for human health (in have been developed in some SW Indian Ocean coun- particular iron, iodine, zinc, calcium, vitamins A and B), tries, mainly to comply with export regulations of foreign and is especially important in the diets of infants, children markets. -

Draft NATIONAL MARICULTURE POLICY 2019

CMFRI Marine Fisheries Policy Series No.17/2020 Draft National Mariculture Policy 2019 (NMP2019) [Report of the Committee constituted by the National Fisheries Development Board (NFDB) Ministry of Fisheries, Animal Husbandry & Dairying, Govt. of India] ISSN: 0972-2351 Published by Dr. A. Gopalakrishnan Director, ICAR-Central Marine Fisheries Research Institute (CMFRI), Post Box No. 1603, Ernakulam North P.O. Kochi- 682 018, Kerala, India Web: www.cmfri.org Design & Layout: Abhilash P.R., CMFRI, Kochi Publication, Production & Coordination: Arun Surendran, Library and Documentation Centre, CMFRI, Kochi Suggested citation: Gopalakrishnan, A., Kirubagaran, R., George John, Ponniah, A.G., Gopakumar, G., Sunilkumar Mohamed K., Krishnan P., Imelda Joseph, Boby Ignatius, Abdul Nazar, A.K., Jayakumar, R., Raju, M.S., Sreepada, R.A., Shinoj, P. and Rajesh N. (2019). Draft National Mariculture Policy 2019 (NMP2019); Report of the Committee constituted by the National Fisheries Development Board (NFDB), Ministry of Fisheries, Animal Husbandry & Dairying, Govt. of India. CMFRI Marine Fisheries Policy Series No.17/2020, 22p. iii Contents Preface iii National Mariculture Policy 2019 (NMP2019) Draft Preamble 01 Vision 01 Mission 01 Definition and Scope 01 Status of Mariculture in India and Opportunities 02 Objectives 04 Mariculture Area Development 04 Leasing and Licensing 05 Mariculture Systems and Species 05 Precautionary Approach to Environmental Sustainability 06 Seed and Feed 07 Food Safety and Health Management 08 Capacity Building and Extension 09 Insurance and Support Services 09 Processing, Value Addition and Market Support 10 Institutional Mechanisms 11 Legal Framework 12 Research and Development (R&D) 12 Way Forward 13 Annexure 1 Constitution of the Committee and its ToR (Letter from NFDB) 17 Annexure 2 Meetings Convened by the Committee 19 Annexure 3 Experts involved in the Consultation Process 20 Acronyms/Abbreviations 21 v Draft National Mariculture Policy 2019 (NMP 2019) National Mariculture Policy 2019 (NMP 2019) Draft 1. -

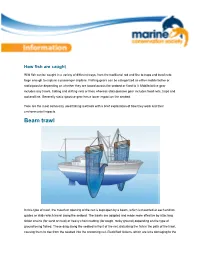

How Fish Are Caught

How fish are caught Wild fish can be caught in a variety of different ways, from the traditional rod and line to traps and trawl nets large enough to capture a passenger airplane. Fishing gears can be categorized as either mobile/active or static/passive depending on whether they are towed across the seabed or fixed to it. Mobile/active gear includes any trawls, trolling and drifting nets or lines whereas static/passive gear includes fixed nets, traps and rod and line. Generally static /passive gear has a lower impact on the seabed. Here are the most commonly used fishing methods with a brief explanation of how they work and their environmental impacts. Beam trawl In this type of trawl, the mouth or opening of the net is kept open by a beam, which is mounted at each end on guides or skids which travel along the seabed. The trawls are adapted and made more effective by attaching tickler chains (for sand or mud) or heavy chain matting (for rough, rocky ground) depending on the type of ground being fished. These drag along the seabed in front of the net, disturbing the fish in the path of the trawl, causing them to rise from the seabed into the oncoming net. Electrified ticklers, which are less damaging to the seabed, have been developed but used only experimentally. Work is also being carried out to investigate whether square mesh panels (see below) fitted in the ‘belly’ or lower panel of the net can reduce the impact of beam trawling on communities living on or in the seabed. -

THE SOCIAL and ENVIRONMENTAL EFFECTS of SHRIMP MARICULTURE: CASE STUDIES of TWO COASTAL VILLAGES in ECUADOR by Mary C. Crider A

THE SOCIAL AND ENVIRONMENTAL EFFECTS OF SHRIMP MARICULTURE: CASE STUDIES OF TWO COASTAL VILLAGES IN ECUADOR by Mary C. Crider A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The Charles E. Schmidt College of Science in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science Florida Atlantic University Boca Raton, FL May 2012 THE SOCIAL AND ENVIRONMENTAL EFFECTS OF SHRIMP MARICULTURE: CASE STUDIES OF TWO COASTAL VILLAGES IN ECUADOR by Mary C. Crider This thesis was prepared under the direction of the candidate's dissertation advisor, Dr. Maria Fadiman, Department of Geosciences, and has been approved by the members ofher supervisory committee. It was submitted to the faculty ofthe Charles E. Schmidt College of Science and was accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree ofMaster ofScience. SUPERVISORY COMMITTEE: ~~ Maria Fadiman, Ph.D. Thesis Advisor su~~~· Tobin Hindle, Ph.D. GaryW.e ,P~ Dean, Charles E. 'Schmidt Col e ofScience B~?Sr;~~ 11 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my main thesis advisor, Dr. Maria Fadiman, without whose guidance this thesis project never would have been completed. I am also grateful for the suggestions from my committee members, Dr. Susan Laramore and Dr. Tobin Hindle. Furthermore, I especially appreciate Dr. Jorge Restrepo’s instruction on my statistics, which was necessary for successful analysis. Additionally, I would like to thank Jatun Sacha, especially the director of the Congal Biomarine Station, Andres Ledergerber, for facilitating my research in the study area. Finally, I would like to express my gratitude toward my local guides, Marisol Gallardo and Carlos Torres, and translators, Eva Gertz, Yani Astudillo, Lucia Ordoñez-Gauger, Samuel Kaa, and Adrian Levrel, for their willingness to help me collect the data.