MBA-Seafood Watch US-Farmed Shrimp Report (Pdf)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SUSTAINABLE FISHERIES and RESPONSIBLE AQUACULTURE: a Guide for USAID Staff and Partners

SUSTAINABLE FISHERIES AND RESPONSIBLE AQUACULTURE: A Guide for USAID Staff and Partners June 2013 ABOUT THIS GUIDE GOAL This guide provides basic information on how to design programs to reform capture fisheries (also referred to as “wild” fisheries) and aquaculture sectors to ensure sound and effective development, environmental sustainability, economic profitability, and social responsibility. To achieve these objectives, this document focuses on ways to reduce the threats to biodiversity and ecosystem productivity through improved governance and more integrated planning and management practices. In the face of food insecurity, global climate change, and increasing population pressures, it is imperative that development programs help to maintain ecosystem resilience and the multiple goods and services that ecosystems provide. Conserving biodiversity and ecosystem functions are central to maintaining ecosystem integrity, health, and productivity. The intent of the guide is not to suggest that fisheries and aquaculture are interchangeable: these sectors are unique although linked. The world cannot afford to neglect global fisheries and expect aquaculture to fill that void. Global food security will not be achievable without reversing the decline of fisheries, restoring fisheries productivity, and moving towards more environmentally friendly and responsible aquaculture. There is a need for reform in both fisheries and aquaculture to reduce their environmental and social impacts. USAID’s experience has shown that well-designed programs can reform capture fisheries management, reducing threats to biodiversity while leading to increased productivity, incomes, and livelihoods. Agency programs have focused on an ecosystem-based approach to management in conjunction with improved governance, secure tenure and access to resources, and the application of modern management practices. -

Nutrition, Feeds and Feed Technology for Mariculture in India Vijayagopal P

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by CMFRI Digital Repository Course Manual Nutrition, Feeds and Feed Technology for Mariculture in India Vijayagopal P. [email protected] Central Marine Fisheries Research Institute, Kochi - 18 Mariculture of finfish on a commercial scale is non-existent in India. CMFRI, RGCA of MPEDA, CIBA are the Institutions promoting finfish mariculture with demonstrated seed production capabilities of Asian seabass (Lates calcarifer), cobia (Rachycentron canadum) and silver pompano (Trachynotus blochii). Seed production is not sufficient enough togo in for commercial scale investment. Requisite private investment has not flown into this segment of aquabusiness and Public Private Partnerships (PPP) are yet to take off. The scenario being this in the case of one (seed) of the two major inputs in this food production system, feeds and feeding, which is the other is the subject of elaboration here. Quality marine fish like king seer, pomfrets and tuna retails at more than Rs.400/- per kg in domestic markets. In metro cities it Rs.1000/- per kg is not surprising. With this purchasing power in the domestic market, most of the farmed marine fish is sold to such a clientele which is ever increasing in India. Therefore, without any assurance of a sustainable supply of such fish from capture fisheries, there is no doubt that we have to farm quality marine fish. With as deficit in seed supply at present, let us examine nutrition, feeds and feed technology required for this farming system in India. Farming sites, technologies of cage fabrication and launch, day-to-day management, social issues, policy, economics and health management, harvest and marketing, development of value chains, traceability and certification are all equally important and may or may not be dealt with in this training programme. -

Can Sustainable Mariculture Match Agriculture's Output?

10/30/2018 Can sustainable mariculture match agriculture’s output? « Global Aquaculture Advocate ENVIRONMENTAL & SOCIAL RESPONSIBILITY (/ADVOCATE/CATEGORY/ENVIRONMENTAL-SOCIAL- RESPONSIBILITY) Can sustainable mariculture match agriculture’s output? Thursday, 18 August 2016 By Amir Neori, Ph.D. A global focus on macroalgae and marine plants will result in many jobs and increased food security A seaweed farmer in Nusa Lembongan gathers edible seaweed that has grown on a rope. Photo by Jean-Marie Hullot. https://www.aquaculturealliance.org/advocate/can-sustainable-mariculture-match-agricultures-output/?headlessPrint=AAAAAPIA9c8r7gs82oWZBA 10/30/2018 Can sustainable mariculture match agriculture’s output? « Global Aquaculture Advocate Currently, there is a signicant production difference between agriculture and aquaculture (an imbalance of around 100 to 1). Improving this relationship represents a signicant challenge to the aquaculture industry. A quantum leap in the scale of global food production is imperative to support increasing food needs on a global scale, as the human population continues to grow along with the additional demand for food. Climate change and its possible impacts on traditional food production practices must also be considered, and mariculture presents a unique opportunity. Agriculture produces about 10 billion tons annually of various products, most of which are plants. However, it is hard to imagine how this gure can grow much further, considering the toll of this production on diminishing resources of arable land, fertilizers and irrigation water. Strikingly, aquaculture production is a mere 1 percent of agriculture production, or about 100 million tons per year (according to FAO reports). This is astonishing in a world whose surface is 70 percent water, most of it an oceanic area that receives most of the world’s solar irradiation and that contains huge amounts of nutrients (e.g., 1011 tons of phosphorus), especially in the Pacic Ocean. -

Fishery Basics – Seafood Markets Types of Fishery Products

Fishery Basics – Seafood Markets Types of Fishery Products Fish products are highly traded and valuable commodities around the world. Seafood products are high in unsaturated fats and contain many proteins and other compounds that enhance good health. Fisheries products can be sold as live, fresh, frozen, preserved, or processed. There are a variety of methods to preserve fishery products, such as fermenting (e.g., fish pastes), drying, smoking (e.g., smoked Salmon), salting, or pickling (e.g., pickled Herring) to name a few. Fish for human consumption can be sold in its entirety or in parts, like filets found in grocery stores. The vast majority of fishery products produced in the world are intended for human consumption. During 2008, 115 million t (253 billion lbs) of the world fish production was marketed and sold for human consumption. The remaining 27 million t (59 billion lbs) of fishery production from 2008 was utilized for non-food purposes. For example, 20.8 million t (45 billion lbs) was used for reduction purposes, creating fishmeal and fish oil to feed livestock or to be used as feed in aquaculture operations. The remainder was used for ornamental and cultural purposes as well as live bait and pharmaceutical uses. Similar to the advancement of fishing gear and navigation technology (See Fishing Gear), there have been many advances in the seafood-processing sector over the years. Prior to these developments, most seafood was only available in areas close to coastal towns. The modern canning process originated in France in the early 1800s. Cold storage and freezing plants, to store excess harvests of seafood, were created as early as 1892. -

Improving Shrimp Practices in Latin America

IMPROVING SHRIMP MARICULTURE in LATIN AMERICA GOOD MANAGEMENT PRACTICES (GMPS) to R EDUCE ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACTS and IMPROVE EFFICIENCY of S HRIMP AQUACULTURE in LATIN AMERICA and an ASSESSMENT of P RACTICES in the HONDURAN SHRIMP INDUSTRY Claude E. Boyd P.O. Box 3074 Auburn,Alabama 36831 U.S.A. Maria C. Haws Coastal Resources Center University of Rhode Island Narragansett, Rhode Island 02882 U.S.A. Bartholomew W. Green Department of Fisheries and Allied Aquaculture Auburn University,Alabama 36849-5419 U.S.A. TABLE of C ONTENTS Preface___________________________________________________________________ 1 1.0 Rationale for Developing GMPs ____________________________________________ 3 2.0 Characteristics of Good Management Practices__________________________________ 5 3.0 Who Can Benefit from Good Management Practices _____________________________ 7 4.0 Methodology Used in Developing Good Management Practices ______________________ 8 5.0 The Scope and Intent of Good Management Practices _____________________________ 10 6.0 Characteristics of the Honduras Shrimp Industry ________________________________ 12 7.0 Site Selection _________________________________________________________ 16 7.1 Topography ______________________________________________________ 17 7.2 Hydrology and Hydrography__________________________________________ 18 7.3 Soil Characteristics ________________________________________________ 18 7.4 Infrastructure and Operational Considerations _____________________________ 19 8.0 Farm Design and Construction _____________________________________________ -

Soil Association Organic Aquaculture Standards

Soil Association Organic aquaculture standards Version 1.3 May 2017 Soil Association organic aquaculture standards Contents OP: Overall principles of organic aquaculture.................................................................... 3 SS: Site selection .............................................................................................................................. 7 OA: Origin of aquaculture animals .......................................................................................... 8 ON: Simultaneous production of organic and non-organic ......................................... 9 AH: Aquaculture husbandry ..................................................................................................... 11 SD: Species-specific production requirements and stocking densities ................. 13 AL: Aquaculture livestock management .............................................................................. 16 AC: Aquatic containment systems ......................................................................................... 19 AM: Antifouling measures and cleaning ............................................................................. 20 FF: Feeding fish, crustaceans and echinoderms ............................................................... 22 FC: Feeding carnivorous aquaculture species ................................................................... 22 FO: Feeding other species .......................................................................................................... 24 -

Aquaponics NOMA New Innovations for Sustainable Aquaculture in the Nordic Countries

NORDIC INNOVATION PUBLICATION 2015:06 // MAY 2015 Aquaponics NOMA New Innovations for Sustainable Aquaculture in the Nordic Countries Aquaponics NOMA (Nordic Marine) New Innovations for Sustainable Aquaculture in the Nordic Countries Author(s): Siv Lene Gangenes Skar, Bioforsk Norway Helge Liltved, NIVA Norway Paul Rye Kledal, IGFF Denmark Rolf Høgberget, NIVA Norway Rannveig Björnsdottir, Matis Iceland Jan Morten Homme, Feedback Aquaculture ANS Norway Sveinbjörn Oddsson, Matorka Iceland Helge Paulsen, DTU-Aqua Denmark Asbjørn Drengstig, AqVisor AS Norway Nick Savidov, AARD, Canada Randi Seljåsen, Bioforsk Norway May 2015 Nordic Innovation publication 2015:06 Aquaponics NOMA (Nordic Marine) – New Innovations for Sustainable Aquaculture in the Nordic Countries Project 11090 Participants Siv Lene Gangenes Skar, Bioforsk/NIBIO Norway, [email protected] Helge Liltved, NIVA/UiA Norway, [email protected] Asbjørn Drengstig, AqVisor AS Norway, [email protected] Jan M. Homme, Feedback Aquaculture Norway, [email protected] Paul Rye Kledal, IGFF Denmark, [email protected] Helge Paulsen, DTU Aqua Denmark, [email protected] Rannveig Björnsdottir, Matis Iceland, [email protected] Sveinbjörn Oddsson, Matorka Iceland, [email protected] Nick Savidov, AARD Canada, [email protected] Key words: aquaponics, bioeconomy, recirculation, nutrients, mass balance, fish nutrition, trout, plant growth, lettuce, herbs, nitrogen, phosphorus, business design, system design, equipment, Nordic, aquaculture, horticulture, RAS. Abstract The main objective of AQUAPONICS NOMA (Nordic Marine) was to establish innovation networks on co-production of plants and fish (aquaponics), and thereby improve Nordic competitiveness in the marine & food sector. To achieve this, aquaponics production units were established in Iceland, Norway and Denmark, adapted to the local needs and regulations. -

Fishery Oceanographic Study on the Baleen Whaling Grounds

FISHERY OCEANOGRAPHIC STUDY ON THE BALEEN WHALING GROUNDS KEIJI NASU INTRODUCTION A Fishery oceanographic study of the whaling grounds seeks to find the factors control ling the abundance of whales in the waters and in general has been a subject of interest to whalers. In the previous paper (Nasu 1963), the author discussed the oceanography and baleen whaling grounds in the subarctic Pacific Ocean. In this paper, the oceanographic environment of the baleen whaling grounds in the coastal region ofJapan, subarctic Pacific Ocean, and Antarctic Ocean are discussed. J apa nese oceanographic observations in the whaling grounds mainly have been carried on by the whaling factory ships and whale making research boats using bathyther mographs and reversing thermomenters. Most observations were made at surface. From the results of the biological studies on the whaling grounds by Marr ( 1956, 1962) and Nemoto (1959) the author presumed that the feeding depth is less than about 50 m. Therefore, this study was made mainly on the oceanographic environ ment of the surface layer of the whaling grounds. In the coastal region of Japan Uda (1953, 1954) plotted the maps of annual whaling grounds for each 10 days and analyzed the relation between the whaling grounds and the hydrographic condition based on data of the daily whaling reports during 1910-1951. A study of the subarctic Pacific Ocean whaling grounds in relation to meteorological and oceanographic conditions was made by U da and Nasu (1956) and Nasu (1957, 1960, 1963). Nemoto (1957, 1959) also had reported in detail on the subject from the point of the food of baleen whales and the ecology of plankton. -

101 Fishing Tips by Capt

101 Fishing Tips By Capt. Lawrence Piper www.TheAnglersMark.com [email protected] 904-557 -1027 Table of Contents Tackle and Angling Page 2 Fish and Fishing Page 5 Fishing Spots Page 13 Trailering and Boating Page 14 General Page 15 1 Amelia Island Back Country Light Tackle Fishing Tips Tackle and Angling 1) I tell my guests who want to learn to fish the back waters “learn your knots”! You don’t have to know a whole bunch but be confident in the ones you’re going to use and know how to tie them good and fast so you can bet back to fishing after you’ve broken off. 2) When fishing with soft plastics keep a tube of Super Glue handy in your tackle box. When you rig the grub on to your jig, place a drop of the glue below the head and then finish pushing the grub up. This will secure the grub better to the jig and help make it last longer. 3) Many anglers get excited when they hook up with big fish. When fishing light tackle, check your drag so that it’s not too tight and the line can pull out. When you hookup, the key is to just keep the pressure on the fish. If you feel any slack, REEL! When the fish is pulling away from you, use the rod and the rod tip action to tire the fish. Slowly work the fish in, lifting up, reeling down. Keep that pressure on! 4) Net a caught fish headfirst. Get the net down in the water and have the angler work the fish towards you and as it tires, bring the fish headfirst into the net. -

International Whaling Commission (IWC)

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Fisheries and for a world without hunger Aquaculture Department Regional Fishery Bodies Summary Descriptions International Whaling Commission (IWC) Objectives Area of competence Species and stocks coverage Members Further information Objectives The main objective of the International Whaling Commission (IWC) is to establish a system of international regulations to ensure proper and effective conservation and management of whale stocks. These regulations must be "such as are necessary to carry out the objectives and purposes of the Convention and to provide for the conservation, development, and optimum utilization of whale resources; must be based on scientific findings; and must take into consideration the interests of the consumers of whale products and the whaling industry." Area of competence The area of competence of the IWC is global. The International Convention for the Regulation of Whaling also applies to factory ships, land stations, and whale catchers under the jurisdiction of the Contracting Governments and to all waters in which whaling is prosecuted by such factory ships, land stations, and whale catchers. FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Department IWC area of competence Launch the RFBs map viewer Species and stocks coverage Blue whale (Balaenoptera musculus); bowhead whale (Balaena mysticetus); Bryde’s whale (Balaenoptera edeni, B. brydei); fin whale (Balaenoptera physalus); gray whale (Eschrichtius robustus); humpback whale (Megaptera novaeangliae); minke whale (Balaenoptera -

SOLUTION: Gathering and Sonic Blasts for Oil Exploration Because These Practices Can Harm and Kill Whales

ENDANGEREDWHALES © Nolan/Greenpeace WE HAVE A PROBLEM: WHAT YOU CAN DO: • Many whale species still face extinction. • Tell the Bush administration to strongly support whale protection so whaling countries get the • Blue whales, the largest animals ever, may now number as message. few as 400.1 • Ask elected officials to press Iceland, Japan • Rogue nations Japan, Norway and Iceland flout the and Norway to respect the commercial whaling international ban on commercial whaling. moratorium. • Other threats facing whales include global warming, toxic • Demand that the U.S. curb global warming pollution dumping, noise pollution and lethal “bycatch” from fishing. and sign the Stockholm Convention, which bans the most harmful chemicals on the planet. • Tell Congress that you oppose sonar intelligence SOLUTION: gathering and sonic blasts for oil exploration because these practices can harm and kill whales. • Japan, Norway and Iceland must join the rest of the world and respect the moratorium on commercial whaling. • The loophole Japan exploits to carry out whaling for “Tomostpeople,whalingisallnineteenth- “scientific” research should be closed. centurystuff.Theyhavenoideaabout • Fishing operations causing large numbers of whale hugefloatingslaughterhouses,steel-hulled bycatch deaths must be cleaned up or stopped. chaserboatswithsonartostalkwhales, • Concerted international action must be taken to stop andharpoonsfiredfromcannons.” other threats to whales including global warming, noise Bob Hunter, pollution, ship strikes and toxic contamination. -

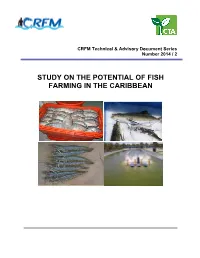

Study on the Potential of Fish Farming in the Caribbean

CRFM Technical & Advisory Document Series Number 2014 / 2 STUDY ON THE POTENTIAL OF FISH FARMING IN THE CARIBBEAN CRFM Technical & Advisory Document - Number 2014 / 2 Study on the Potential of Fish Farming in the Caribbean Prepared by: George Myvett, Milton Haughton and Peter A. Murray CRFM Secretariat Belize 2014 2 CRFM Technical & Advisory Document - Number 2014 / 2 Study on the Potential of Fish Farming in the Caribbean © CRFM 2014 All rights reserved. Reproduction, dissemination and use of material in this publication for educational or non-commercial purposes are authorised without prior written permission of the CRFM, provided the source is fully acknowledged. No part of this publication may be reproduced, disseminated on used for any commercial purposes or resold without the prior written permission of the CRFM. Correct Citation: CRFM, 2014. Study on the Potential of Fish Farming in the Caribbean. CRFM Technical & Advisory Document No 2014 / 2. P78 ISSN : 1995-1132 Published by the Caribbean Regional Fisheries Mechanism Secretariat Belize This document has been produced with financial assistance of the Technical Centre for Agricultural and Rural Coordination (CTA) which funded the Consultancy. However, the views expressed herein are those of the author and CRFM Secretariat, and can therefore in no way be taken to reflect the official opinions of CTA. 3 Contents Contents ........................................................................................................................................................ 1 Glossary