The Mere Possesion of a Pipe Bomb

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Urban Terrorism: Strategies for Mitigating Terrorist Attacks Against the Domestic Urban Environment

Old Dominion University ODU Digital Commons Theses and Dissertations in Urban Services - Urban Management College of Business (Strome) Spring 2001 Urban Terrorism: Strategies for Mitigating Terrorist Attacks Against the Domestic Urban Environment John J. Kiefer Old Dominion University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/urbanservices_management_etds Part of the Public Administration Commons, Public Policy Commons, and the Urban Studies and Planning Commons Recommended Citation Kiefer, John J.. "Urban Terrorism: Strategies for Mitigating Terrorist Attacks Against the Domestic Urban Environment" (2001). Doctor of Philosophy (PhD), dissertation, , Old Dominion University, DOI: 10.25777/ 0b83-mp91 https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/urbanservices_management_etds/29 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Business (Strome) at ODU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations in Urban Services - Urban Management by an authorized administrator of ODU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. URBAN TERRORISM: STRATEGIES FOR MITIGATING TERRORIST ATTACKS AGAINST THE DOMESTIC URBAN ENVIRONMENT by John J. Kiefer B.B.A. August 1975, University of Mississippi M.S.A. August 1989, Central Michigan University M.U.S. May 1997, Old Dominion University A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of Old Dominion University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY URBAN SERVICES OLD DOMINION UNIVERSITY May 2001 Reviewed by: Approved by: Wol indur tfChair) College of Business and Public Administration Leonard I. Ruchelman (Member) Berhanu Mengistu^Ph.D. G. William Whitehurst (Member) Program Director Graduate Center for Urban Studies And Public Administration Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. -

FBI 1996 US Terrorism Report

TERRoRISM in the United States 1996 Counterterrorism Threat Assessment and Warning Unit National Security Division I N T R O DUCTION United States soil was the site of three terrorist incidents during 1996. The pipe bomb explosion during the Summer Olympic Games in Centennial Olympic Park that killed two and the robberies and bombings carried out in April and July 1996 by members of a group known as the Phineas Priesthood underscored the ever-present threat that exists from individuals determined to use violence to advance particular causes. The FBI successfully prevented five planned acts of domestic terrorism in 1996. These preventions thwarted attacks on law enforcement officials, prevented planned bombings of federal buildings, and halted plots to destroy domestic infrastructure. The explosion of TWA Flight 800 over the Atlantic Ocean near Long Island, New York, on July 17, 1996, resulted in initial speculation that a terrorist attack may have been the cause and served to highlight the potential danger terrorists pose to U.S. civil aviation. The FBI, along with the National Transportation Safety Board, devoted significant resources to the criminal investigation throughout 1996. Evidence did not implicate a criminal or terrorist act by year’s-end. Threats from domestic terrorism continue to build as militia extremists, particularly those operating in the western United States, gain new adherents, stockpile weapons, and prepare for armed conflict with the federal government. The potential for domestic right-wing terrorism remains a threat. Special interest groups also endure as a threat that could surface at any time. International terrorists threaten the United States directly. -

Bombing for Justice: Urban Terrorism in New York City from the 1960S Through the 1980S

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Publications and Research John Jay College of Criminal Justice 2014 Bombing for Justice: Urban Terrorism in New York City from the 1960s through the 1980s Jeffrey A. Kroessler John Jay College of Criminal Justice How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/jj_pubs/38 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] Bombing for Justice: Urban Terrorism in New York City from the 1960s through to the 1980s Jeffrey A. Kroessler John Jay College of Criminal Justice, City University of New York ew York is no stranger to explosives. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the Black Hand, forerunners of the Mafia, planted bombs at stores and residences belonging to successful NItalians as a tactic in extortion schemes. To combat this evil, the New York Police Department (NYPD) founded the Italian Squad under Lieutenant Joseph Petrosino, who enthusiastically pursued those gangsters. Petrosino was assassinated in Palermo, Sicily, while investigating the criminal back- ground of mobsters active in New York. The Italian Squad was the gen- esis of today’s Bomb Squad. In the early decades of the twentieth century, anarchists and labor radicals planted bombs, the most devastating the 63 64 Criminal Justice and Law Enforcement noontime explosion on Wall Street in 1920. That crime was never solved.1 The city has also had its share of lunatics. -

Part II EXPLOSIVES INCIDENTS ANALYSIS

If you have issues viewing or .accessing this file contact us at NCJRS.gov. lIP :. I , . •• , .. I , It • ~ • -. I .. • r • -. I , I "$: .; ~.. ,~--.~.~. " I I I I ,.. .~;- ""', ....... ~~-, ~,-- - --------~- .. ". ---------------- Cover: Top Photo: The results of an explosive device that detonated beneath the vehicle as it was traveling through the Kansas City, Missouri, area. The detonation ldlled the driver and severely injured the driver's wife. (Photo .courtesy of Dan Dyer, the News Leader Newspaper.) Bottom Photo: The scene of an explosion in Duncanville, Alabama, that killed the two occupants of the trailer. 12608.1 U.S. Department of Justice National Institute of Justice This document has been reproduced exactly as received from the person or organization originating it. Points of view or opinions stated In this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the National Institute of Justice. Permission to reproduce this "'IJIi". material has been granted by U.S. Dept. of Treasury/Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco & Firearms to the National Criminal Justice Reference Service (NCJRS). Further reproduction outside of the NCJRS system requires permis sion of the ~ owner. Dedication This year we have seen a significant increase in the number of injuries sustained by our State and local counterparts in the law enforcement and fire service communities. The dangers inherent to their line of work are a given; however, the ever-changing environment in which they work has increased these dangers. Booby-trapped drug operations and illicit explosives manufac turing operations are but a few of the criminal activities that present such dangers, not only to them but to the public as well. -

“A Peace of Sorts”: a Cultural History of the Belfast Agreement, 1998 to 2007 Eamonn Mcnamara

“A Peace of Sorts”: A Cultural History of the Belfast Agreement, 1998 to 2007 Eamonn McNamara A thesis submitted for the degree of Master of Philosophy, Australian National University, March 2017 Declaration ii Acknowledgements I would first like to thank Professor Nicholas Brown who agreed to supervise me back in October 2014. Your generosity, insight, patience and hard work have made this thesis what it is. I would also like to thank Dr Ben Mercer, your helpful and perceptive insights not only contributed enormously to my thesis, but helped fund my research by hiring and mentoring me as a tutor. Thank you to Emeritus Professor Elizabeth Malcolm whose knowledge and experience thoroughly enhanced this thesis. I could not have asked for a better panel. I would also like to thank the academic and administrative staff of the ANU’s School of History for their encouragement and support, in Monday afternoon tea, seminars throughout my candidature and especially useful feedback during my Thesis Proposal and Pre-Submission Presentations. I would like to thank the McClay Library at Queen’s University Belfast for allowing me access to their collections and the generous staff of the Linen Hall Library, Belfast City Library and Belfast’s Newspaper Library for all their help. Also thanks to my local libraries, the NLA and the ANU’s Chifley and Menzies libraries. A big thank you to Niamh Baker of the BBC Archives in Belfast for allowing me access to the collection. I would also like to acknowledge Bertie Ahern, Seán Neeson and John Lindsay for their insightful interviews and conversations that added a personal dimension to this thesis. -

Faculty Research: Violence and Family in Northern Ireland Patricia J

Bridgewater Review Volume 25 | Issue 1 Article 10 Jun-2006 Faculty Research: Violence and Family in Northern Ireland Patricia J. Fanning Bridgewater State College, [email protected] Ruth Hannon Bridgewater State College, [email protected] Recommended Citation Fanning, Patricia J. and Hannon, Ruth (2006). Faculty Research: Violence and Family in Northern Ireland. Bridgewater Review, 25(1), 23-24. Available at: http://vc.bridgew.edu/br_rev/vol25/iss1/10 This item is available as part of Virtual Commons, the open-access institutional repository of Bridgewater State University, Bridgewater, Massachusetts. Faculty Research Violence and Family in Northern Ireland E C N For several years Dr. Ruth Hannon packed with nails, metal frag- O of the Psychology Department has ments, and a blasting cap, Y P studied working parents and their exploded on the schoolhouse children’s perceptions of their parents’ steps. Dozens of children, ages 4 work. In interviewing some four dozen to 11 were quickly surrounded by agal children and families, mostly from New riot police and removed from the M England, she found that an overrid- schoolyard. ing concern for those trying to balance How did such events affect family a… work and family was safety. Parents N life, Hannon wondered. How do worried about the availability of safe working parents cope with this UA yet affordable day care, after-school IJ kind of danger and how do the programs, and other after-school ar- children perceive the situation? rangements, even in ostensibly safe, O T Dr. Hannon also knew from her G suburban neighborhoods. How, she research that women were enter- E I wondered, do families manage in areas From Page 19 ing the workforce in Northern D n that are inherently unsafe? Although his or her individual work that would later feed the screens, and free local beer. -

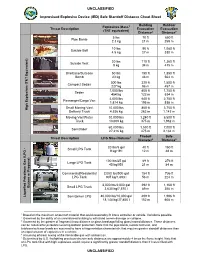

Improvised Explosive Device (IED) Safe Standoff Distance Cheat Sheet

UNCLASSIFIED Improvised Explosive Device (IED) Safe Standoff Distance Cheat Sheet Building Outdoor Explosives Mass1 Threat Description Evacuation Evacuation (TNT equivalent) Distance2 Distance3 5 lbs 70 ft 850 ft Pipe Bomb 2.3 kg 21 m 259 m 10 lbs 90 ft 1,080 ft Suicide Belt 4.5 kg 27 m 330 m 20 lbs 110 ft 1,360 ft Suicide Vest 9 kg 34 m 415 m Briefcase/Suitcase 50 lbs 150 ft 1,850 ft Bomb 23 kg 46 m 564 m 500 lbs 320 ft 1,500 ft Compact Sedan 227 kg 98 m 457 m 1,000 lbs 400 ft 1,750 ft Sedan 454 kg 122 m 534 m 4,000 lbs 640 ft 2,750 ft Passenger/Cargo Van 1,814 kg 195 m 838 m Small Moving Van/ 10,000 lbs 860 ft 3,750 ft High Explosives (TNT Equivalent) Delivery Truck 4,536 kg 263 m 1,143 m Moving Van/Water 30,000 lbs 1,240 ft 6,500 ft Truck 13,608 kg 375 m 1,982 m 60,000 lbs 1,570 ft 7,000 ft Semitrailer 27,216 kg 475 m 2,134 m Fireball Safe Threat Description LPG Mass/Volume1 Diameter4 Distance5 20 lbs/5 gal 40 ft 160 ft - Small LPG Tank 9 kg/19 l 12 m 48 m 100 lbs/25 gal 69 ft 276 ft Large LPG Tank 45 kg/95 l 21 m 84 m Commercial/Residential 2,000 lbs/500 gal 184 ft 736 ft LPG Tank 907 kg/1,893 l 56 m 224 m 8,000 lbs/2,000 gal 292 ft 1,168 ft Butane or Propane) Small LPG Truck 3,630 kg/7,570 l 89 m 356 m Liquefied Petroleum Gas (LPG Semitanker LPG 40,000 lbs/10,000 gal 499 ft 1,996 ft 18,144 kg/37,850 l 152 m 608 m 1 Based on the maximum amount of material that could reasonably fit into a container or vehicle. -

V- Ciaran Maxwell Sentencing Remarks

The Queen -v- Ciaran Maxwell In the Central Criminal Court Sentencing remarks of Mr Justice Sweeney 31 July 2017 Ciaran Maxwell, you are now aged 31 and have no previous convictions. You have pleaded guilty to 3 offences, each of which was committed whilst you were a serving Royal Marine Commando, latterly in the rank of Lance Corporal – having enlisted in September 2010. Over the years between January 2011 and your arrest in August 2016, in flagrant breach of trust and in betrayal of your position in the Armed Forces, you took part in the preparation of terrorist acts (Count 1). As the Particulars of that offence make clear, with the intention of assisting another to commit acts of terrorism, you engaged in conduct in preparation for giving effect to that intention namely: (1) Research resulting in the creation of a library of documents providing information of a kind likely to be useful to a person committing or preparing an act of terrorism – specifically information regarding the manufacture of explosive substances, the construction of explosive devices, and tactics used by terrorist organisations. (2) Research resulting in the creation of a library of documents providing information of a kind likely to be useful to a person committing or preparing an act of terrorism – specifically, maps, plans, and lists of potential targets for a terrorist attack. (3) Purchasing or otherwise obtaining articles for a terrorist purpose connected with the commission, preparation or instigation of an act of terrorism – specifically chemicals and components to be used in the manufacture of explosive substances and the construction of explosive devices; an image of an adapted PSNI card; and items of PSNI uniform. -

Northern Ireland) Act 2007

REPORT OF THE INDEPENDENT REVIEWER JUSTICE AND SECURITY (NORTHERN IRELAND) ACT 2007 THIRD REPORT: 2009-2010 Robert Whalley CB November 2010 The Rt Hon Owen Paterson MP Secretary of State for Northern Ireland Independent Reviewer of the Justice and Security (Northern Ireland) Act 2007 By his letter to me of 22 May 2008, your predecessor, the Rt Hon Shaun Woodward MP, appointed me as Independent Reviewer under section 40 of the Justice and Security (Northern Ireland) Act 2007. Mr Woodward set out my Terms of Reference thus: “The overall aim of the Independent Reviewer will be, in accordance with the Act: • to review the operation of sections 21 to 32 of the Act and those who use or are affected by those sections; • to review the procedures adopted by the GOC NI for receiving, investigating and responding to complaints; • and to report annually to the Secretary of State The Reviewer will act in accordance with any request by the Secretary of State to include in a review specified matters over above those outlined in Sections 21 to 32 of the Act and the GOC remit outlined above. • The Reviewer may make recommendations to be considered by the Secretary of State on whether to repeal powers in the Act”. I submitted my first report to Mr Woodward on 31 October 2008 and my second on 7 November 2009. Both are available on the Parliamentary website: Link to First Report Link to Second Report I now have pleasure in submitting to you my third report, which covers the period from 1 August 2009 to 31 July 2010. -

The Return of the Militants: Violent Dissident Republicanism

The Return of the Militants: Violent Dissident Republicanism A policy report published by the International Centre for the Study of Radicalisation and Political Violence (ICSR) ABOUT THE AUTHOR Dr. Martyn Frampton is Lecturer in Modern/ Contemporary History at Queen Mary, University of London. He was formerly a Research Fellow at Peterhouse in Cambridge. He is an expert on the Irish republican movement and his books, The Long March: The Political Strategy of Sinn Féin, 1981–2007 and Talking to Terrorists: Making Peace in Northern Ireland and the Basque Country, were published in 2009, by Palgrave Macmillan and Hurst and Co. respectively. ABOUT ICSR The International Centre for the Study of Radicalisation and Political Violence (ICSR) is a unique partnership in which King’s College London, the University of Pennsylvania, the Interdisciplinary Center Herzliya (Israel) and the Regional Center for Conflict Prevention Amman (Jordan) are equal stakeholders. The aim and mission of ICSR is to bring together knowledge and leadership to counter the growth of radicalisation and political violence. For more information, please visit www.icsr.info. CONTACT DETAILS For questions, queries and additional copies of this report, please contact: ICSR King’s College London 138 –142 Strand London WC2R 1HH United Kingdom T. + 44 20 7848 2065 F. + 44 20 7848 2748 E. [email protected] Like all other ICSR publications, this report can be downloaded free of charge from the ICSR website at www.icsr.info. © ICSR 2010 Prologue ince the Belfast Friday Agreement of 1998, the security situation in Northern Ireland has improved immeasurably. S The Provisional IRA and the main loyalist terrorist groups have called an end to their campaigns and their weapons have been decommissioned under an internationally monitored process. -

Terrorism in the United States 1996

TERRoRISM in the United States 1996 Counterterrorism Threat Assessment and Warning Unit National Security Division I N T R O DUCTION United States soil was the site of three terrorist incidents during 1996. The pipe bomb explosion during the Summer Olympic Games in Centennial Olympic Park that killed two and the robberies and bombings carried out in April and July 1996 by members of a group known as the Phineas Priesthood underscored the ever-present threat that exists from individuals determined to use violence to advance particular causes. The FBI successfully prevented five planned acts of domestic terrorism in 1996. These preventions thwarted attacks on law enforcement officials, prevented planned bombings of federal buildings, and halted plots to destroy domestic infrastructure. The explosion of TWA Flight 800 over the Atlantic Ocean near Long Island, New York, on July 17, 1996, resulted in initial speculation that a terrorist attack may have been the cause and served to highlight the potential danger terrorists pose to U.S. civil aviation. The FBI, along with the National Transportation Safety Board, devoted significant resources to the criminal investigation throughout 1996. Evidence did not implicate a criminal or terrorist act by year’s-end. Threats from domestic terrorism continue to build as militia extremists, particularly those operating in the western United States, gain new adherents, stockpile weapons, and prepare for armed conflict with the federal government. The potential for domestic right-wing terrorism remains a threat. Special interest groups also endure as a threat that could surface at any time. International terrorists threaten the United States directly. -

Explosives Recognition and Response for First Responders

Explosives Recognition and Response for First Responders I. Training Briefing A. A brief history of the civilian Bomb Squads in the United States. 1. Hazardous Devices School: began official training of all civilian Bomb Technicians in 1971. a. Butte County has had an accredited Bomb Squad since the early 1990’s. (1) Information about the current members. 2. Training requirements for Bomb Technicians B. Overview of training. 1. Commercial explosives, military ordnance, Improvised Explosive Devices (IEDs), statutes and response to possible explosives related incident. II. Chemical Explosives A. Rapid conversion of a solid or liquid explosive compound into gases. 1. Explosion - a rapid form of combustion. 2. The speed of the burning reaction constitutes the difference between combustion, explosion, and detonation. a. Detonation is defined as instantaneous combustion. B. Effects of an explosion 1. Blast Pressure a. Detonation produces expanding gases in a period of 1/10,000 of a second and reaches velocities of up to 13,000 mile per hour, producing 700 tons of pressure per square inch. b. The blast front will vaporize flesh and bone and pulverize concrete. c. Mass of expanding gas rolls outward in a spherical pattern like a giant wave. 2. Fragmentation a. Pipe bomb will reach about the same velocity as a military rifle bullet - approximately 2,700 feet per second. 3. Incendiary Thermal Effect a. High explosives will reach temperatures of about 8,000 degrees F. C. Explosives 1. Classification a. Low Explosives (1) Deflagrate (burn) rather than detonate (a) Burning is transmitted from one grain to the next Training OuTline 1 (2) Initiated by a flame/safety fuse (3) Primarily used as propellants and have pushing or heaving effect (4) Black powder/smokeless powder (5) Must be confined to explode (6) Burning rate of under 3,280 fps b.