Urban Terrorism: Strategies for Mitigating Terrorist Attacks Against the Domestic Urban Environment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Profiles of Perpetrators of Terrorism in the United States, 1970-2013, Final Report to Resilient Systems Division, DHS Science A

Profiles of Perpetrators of Terrorism in the United States, 1970-2013 Final Report to Resilient Systems Division, DHS Science and Technology Directorate December 2014 National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism A Department of Homeland Security Science and Technology Center of Excellence Based at the University of Maryland 8400 Baltimore Ave, Suite 250 • College Park, MD 20740 • 301.405.6600 www.start.umd.edu National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism A Department of Homeland Security Science and Technology Center of Excellence About This Report The lead author of this final report is Erin Miller at the University of Maryland. Questions about this report should be directed to Erin Miller at [email protected]. An interim report was co-authored by Kathleen Smarick and Joseph Simone, Jr. (University of Maryland) in 2011. This research was supported by the Resilient Systems Division of the Science and Technology Directorate of the U.S. Department of Homeland Security through Award Number 2009-ST-108-LR0003 made to the National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism (START). The views and conclusions contained in this document are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as necessarily representing the official policies, either expressed or implied, of the U.S. Department of Homeland Security or START. This report is part of a series in support of the Prevent/Deter program. The goal of this program is to sponsor research that will aid the intelligence and law enforcement communities in assessing potential terrorist threats and support policymakers in developing prevention efforts. -

FBI 1996 US Terrorism Report

TERRoRISM in the United States 1996 Counterterrorism Threat Assessment and Warning Unit National Security Division I N T R O DUCTION United States soil was the site of three terrorist incidents during 1996. The pipe bomb explosion during the Summer Olympic Games in Centennial Olympic Park that killed two and the robberies and bombings carried out in April and July 1996 by members of a group known as the Phineas Priesthood underscored the ever-present threat that exists from individuals determined to use violence to advance particular causes. The FBI successfully prevented five planned acts of domestic terrorism in 1996. These preventions thwarted attacks on law enforcement officials, prevented planned bombings of federal buildings, and halted plots to destroy domestic infrastructure. The explosion of TWA Flight 800 over the Atlantic Ocean near Long Island, New York, on July 17, 1996, resulted in initial speculation that a terrorist attack may have been the cause and served to highlight the potential danger terrorists pose to U.S. civil aviation. The FBI, along with the National Transportation Safety Board, devoted significant resources to the criminal investigation throughout 1996. Evidence did not implicate a criminal or terrorist act by year’s-end. Threats from domestic terrorism continue to build as militia extremists, particularly those operating in the western United States, gain new adherents, stockpile weapons, and prepare for armed conflict with the federal government. The potential for domestic right-wing terrorism remains a threat. Special interest groups also endure as a threat that could surface at any time. International terrorists threaten the United States directly. -

I: to the N~'Iiqnal Grlmlnal Justice Reference Service (NCJRS)

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file contact us at NCJRS.gov. • .. -~.• -,- ''''' ....'1 r: .~ ~ .....,J ... J 'IJ'·· . " " ..........~~ ' .... ,...-, 107701- U.S. Departmtnt of JUltlce Nationallnllllute of JUllice 107706 1 This document has been reproduced exactly as received from the .. person or organization originating It. Polnle! of view or opinions stated In this dllcument are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official pOSition or policies of the Natlonallnstllule 01 Justice. \ Permission to reproduce this copyrighted material has been granted by , FBI LaW Enforcem:m.t Bulletin I: to the N~'IIQnal Grlmlnal Justice Reference Service (NCJRS). Further reproduOtlon outside of Ihe NCJRS system requires permis sion oIlhe copyright owner. I' aitJ • haA .. ~"'. ~ Ocfober 1987, Volume 56, Number 11 fiLl l1e f; L,~~l! ~~#Bglf 1 Terrorism Today 107 7 t:)1 Ci By Oliver B. Revell 167702. Domestic Terrorism In the 1980's ~ By John W. Harris, Jr. '. I C)7 7CJ3 The FBI and Terrorism ~ By Steven L. Pomerantz /6770,( Irish Terrorism Investigations E By J.L. Stone, Jr. ( a 770$ ~. Narco-Terrorism -- By Daniel Boyce .,. .. [28"_ FBI's Expanding Role In International Terrorism Investigations By D.F. Martell m Law Enforcement Bulletin United States Department of Justice Published by the Office of Publlo Affairs th.COil.r: Federal Bureau of Investigation Milt Ahlerlch, Acting Assistant Director This I!lsue of the Bullelln Is a specl.1 report on Washington, DC 2Q535 terrorism. Cover design by John E. Ott. Edltor-Thom:ls J. OC:lkln JOhil E. Otto, ActIng DIrector Assistant Editor-Kathryn E. -

Patterns of Terrorism in the United States, 1970-2013

Patterns of Terrorism in the United States, 1970-2013 Final Report to Resilient Systems Division, DHS Science and Technology Directorate October 2014 National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism A Department of Homeland Security Science and Technology Center of Excellence Based at the University of Maryland 8400 Baltimore Ave, Suite 250 • College Park, MD 20740 • 301.405.6600 www.start.umd.edu National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism A Department of Homeland Security Science and Technology Center of Excellence About This Report The author of this report is Erin Miller at the University of Maryland. Questions about this report should be directed to Erin Miller at [email protected]. The initial collection of data for the Global Terrorism Database (GTD) data was carried out by the Pinkerton Global Intelligence Services (PGIS) between 1970 and 1997 and was donated to the University of Maryland in 2001. Digitizing and validating the original GTD data from 1970 to 1997 was funded by a grant from the National Institute of Justice in 2004 (PIs Gary LaFree and Laura Dugan; grant number: NIJ2002-DT-CX-0001) and in 2005 as part of the START Center of Excellence by the Department of Homeland Security Science and Technology Directorate (DHS S&T), Office of University Programs (PI Gary LaFree; grant numbers N00140510629 and 2008-ST-061-ST0004). Data collection for incidents that occurred between January 1998 and March 2008 and updates to the earlier data to make it consistent with new GTD coding criteria were funded by the DHS S&T Human Factors/Behavioral Sciences Division (HFD) (PIs Gary LaFree and Gary Ackerman; contract number HSHQDC-05-X-00482) and conducted by database staff at the National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism (START) and the Center for Terrorism and Intelligence Studies (CETIS). -

Fugitive Life: Race, Gender, and the Rise of the Neoliberal-Carceral State

Fugitive Life: Race, Gender, and the Rise of the Neoliberal-Carceral State A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Stephen Dillon IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Regina Kunzel, Co-adviser Roderick Ferguson, Co-adviser May 2013 © Stephen Dillon, 2013 Acknowledgements Like so many of life’s joys, struggles, and accomplishments, this project would not have been possible without a vast community of friends, colleagues, mentors, and family. Before beginning the dissertation, I heard tales of its brutality, its crushing weight, and its endlessness. I heard stories of dropouts, madness, uncontrollable rage, and deep sadness. I heard rumors of people who lost time, love, and their curiosity. I was prepared to work 80 hours a week and to forget how to sleep. I was prepared to lose myself as so many said would happen. The support, love, and encouragement of those around me means I look back on writing this project with excitement, nostalgia, and appreciation. I am deeply humbled by the time, energy, and creativity that so many people loaned me. I hope one ounce of that collective passion shows on these pages. Without those listed here, and so many others, the stories I heard might have become more than gossip in the hallway or rumors over drinks. I will be forever indebted to Rod Ferguson’s simple yet life-altering advice: “write for one hour a day.” Adhering to this rule meant that writing became a part of me like never before. -

DOC 501 Prairie Fire Organizing Committee/John Brown Book Club

DOC 501 Prairie Fire Organizing Committee/John Brown Book Club Prairie Fire Organizing Committee Publications Date Range Organizational Body Subjects Formats General Description of Publication 1976-1995 Prairie Fire Organizing Prison, Political Prisoners, Human Rights, Black liberation, Periodicals, Publications by John Brown Book Club include Breakthrough, Committee/John Brown Book Chicano, Education, Gay/Lesbian, Immigration, Indigenous pamphlets political journal of Prairie Fire Organizing Committee (PFOC), Club struggle, Middle East, Militarism, National Liberation, Native published from 1977 to 1995; other documents published by American, Police, Political Prisoners, Prison, Women, AIDS, PFOC Anti-imperialism, Anti-racism, Anti-war, Apartheid, Aztlan, Black August, Clandestinity, COINTELPRO, Colonialism, Gender, High School, Kurds, Egypt, El Salvador, Eritrea, Feminism, Gentrification, Haiti, Israel, Nicaragua, Palestine, Puerto Rico, Racism, Resistance, Soviet Union/Russia, Zimbabwe, Philippines, Male Supremacy, Weather Underground Organization, Namibia, East Timor, Environmental Justice, Bosnia, Genetic Engineering, White Supremacy, Poetry, Gender, Environment, Health Care, Eritrea, Cuba, Burma, Hawai'i, Mexico, Religion, Africa, Chile, For other information about Prairie Fire Organizing Committee see the website pfoc.org [doesn't exist yet]. Freedom Archives [email protected] DOC 501 Prairie Fire Organizing Committee/John Brown Book Club Prairie Fire Organizing Committee Publications Keywords Azania, Torture, El Salvador, -

The Anti Law Enforcement Bandwagon Is Overcrowded Scapegoating the Police for Society’S Ills Takes the Heat Off Politicians and Bureaucrats

LEBRATIN CE G FRANCIS N CO SA 40YEARS P O LIC E W O S M ER EN OFFIC c Official Publication Of The C SAN FRANCISCO POLICE OFFICERS ASSOCIATION This Publication was Produced and Printed in California, USA ✯ Buy American ✯ Support Local Business VOLUME 47, NUMBER 7 SAN FRANCISCO, JULY 2015 www.sfpoa.org “Enough!” The Anti Law Enforcement Bandwagon is Overcrowded Scapegoating the Police for Society’s Ills Takes the Heat off Politicians and Bureaucrats By Martin Halloran as well as in the Public Defender’s Of- women of the SFPD are reviewed by African American youth from the Bay- SFPOA President fice. The common denominator is that both civilian and government enti- view/Hunters Point on a trip to West we are all human and prone to make ties. I believe that accountability and Africa to learn about their ancestral As the anti law enforcement rhetoric mistakes. The question is can we learn responsibility rest not only with the heritage. Known as Operation Genesis, continues to flood the media print and and advance from those mistakes? SFPD but with all members of our the program was primarily funded by airways in this country, and as certain When problems have arisen with community. These include faith-based the Department and the POA. Also, groups and politicians are jumping on the SFPD, our Chief has taken swift leaders, community activists, elected Officer Todd Burkes of Mission Station this bandwagon to bolster their own action. The Chief has demonstrated officials, and yes even those accused of recently escorted a youth group from status or posture for a possible better more transparency, and has been more violating the law. -

Bombing for Justice: Urban Terrorism in New York City from the 1960S Through the 1980S

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Publications and Research John Jay College of Criminal Justice 2014 Bombing for Justice: Urban Terrorism in New York City from the 1960s through the 1980s Jeffrey A. Kroessler John Jay College of Criminal Justice How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/jj_pubs/38 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] Bombing for Justice: Urban Terrorism in New York City from the 1960s through to the 1980s Jeffrey A. Kroessler John Jay College of Criminal Justice, City University of New York ew York is no stranger to explosives. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the Black Hand, forerunners of the Mafia, planted bombs at stores and residences belonging to successful NItalians as a tactic in extortion schemes. To combat this evil, the New York Police Department (NYPD) founded the Italian Squad under Lieutenant Joseph Petrosino, who enthusiastically pursued those gangsters. Petrosino was assassinated in Palermo, Sicily, while investigating the criminal back- ground of mobsters active in New York. The Italian Squad was the gen- esis of today’s Bomb Squad. In the early decades of the twentieth century, anarchists and labor radicals planted bombs, the most devastating the 63 64 Criminal Justice and Law Enforcement noontime explosion on Wall Street in 1920. That crime was never solved.1 The city has also had its share of lunatics. -

Part II EXPLOSIVES INCIDENTS ANALYSIS

If you have issues viewing or .accessing this file contact us at NCJRS.gov. lIP :. I , . •• , .. I , It • ~ • -. I .. • r • -. I , I "$: .; ~.. ,~--.~.~. " I I I I ,.. .~;- ""', ....... ~~-, ~,-- - --------~- .. ". ---------------- Cover: Top Photo: The results of an explosive device that detonated beneath the vehicle as it was traveling through the Kansas City, Missouri, area. The detonation ldlled the driver and severely injured the driver's wife. (Photo .courtesy of Dan Dyer, the News Leader Newspaper.) Bottom Photo: The scene of an explosion in Duncanville, Alabama, that killed the two occupants of the trailer. 12608.1 U.S. Department of Justice National Institute of Justice This document has been reproduced exactly as received from the person or organization originating it. Points of view or opinions stated In this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the National Institute of Justice. Permission to reproduce this "'IJIi". material has been granted by U.S. Dept. of Treasury/Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco & Firearms to the National Criminal Justice Reference Service (NCJRS). Further reproduction outside of the NCJRS system requires permis sion of the ~ owner. Dedication This year we have seen a significant increase in the number of injuries sustained by our State and local counterparts in the law enforcement and fire service communities. The dangers inherent to their line of work are a given; however, the ever-changing environment in which they work has increased these dangers. Booby-trapped drug operations and illicit explosives manufac turing operations are but a few of the criminal activities that present such dangers, not only to them but to the public as well. -

“A Peace of Sorts”: a Cultural History of the Belfast Agreement, 1998 to 2007 Eamonn Mcnamara

“A Peace of Sorts”: A Cultural History of the Belfast Agreement, 1998 to 2007 Eamonn McNamara A thesis submitted for the degree of Master of Philosophy, Australian National University, March 2017 Declaration ii Acknowledgements I would first like to thank Professor Nicholas Brown who agreed to supervise me back in October 2014. Your generosity, insight, patience and hard work have made this thesis what it is. I would also like to thank Dr Ben Mercer, your helpful and perceptive insights not only contributed enormously to my thesis, but helped fund my research by hiring and mentoring me as a tutor. Thank you to Emeritus Professor Elizabeth Malcolm whose knowledge and experience thoroughly enhanced this thesis. I could not have asked for a better panel. I would also like to thank the academic and administrative staff of the ANU’s School of History for their encouragement and support, in Monday afternoon tea, seminars throughout my candidature and especially useful feedback during my Thesis Proposal and Pre-Submission Presentations. I would like to thank the McClay Library at Queen’s University Belfast for allowing me access to their collections and the generous staff of the Linen Hall Library, Belfast City Library and Belfast’s Newspaper Library for all their help. Also thanks to my local libraries, the NLA and the ANU’s Chifley and Menzies libraries. A big thank you to Niamh Baker of the BBC Archives in Belfast for allowing me access to the collection. I would also like to acknowledge Bertie Ahern, Seán Neeson and John Lindsay for their insightful interviews and conversations that added a personal dimension to this thesis. -

Faculty Research: Violence and Family in Northern Ireland Patricia J

Bridgewater Review Volume 25 | Issue 1 Article 10 Jun-2006 Faculty Research: Violence and Family in Northern Ireland Patricia J. Fanning Bridgewater State College, [email protected] Ruth Hannon Bridgewater State College, [email protected] Recommended Citation Fanning, Patricia J. and Hannon, Ruth (2006). Faculty Research: Violence and Family in Northern Ireland. Bridgewater Review, 25(1), 23-24. Available at: http://vc.bridgew.edu/br_rev/vol25/iss1/10 This item is available as part of Virtual Commons, the open-access institutional repository of Bridgewater State University, Bridgewater, Massachusetts. Faculty Research Violence and Family in Northern Ireland E C N For several years Dr. Ruth Hannon packed with nails, metal frag- O of the Psychology Department has ments, and a blasting cap, Y P studied working parents and their exploded on the schoolhouse children’s perceptions of their parents’ steps. Dozens of children, ages 4 work. In interviewing some four dozen to 11 were quickly surrounded by agal children and families, mostly from New riot police and removed from the M England, she found that an overrid- schoolyard. ing concern for those trying to balance How did such events affect family a… work and family was safety. Parents N life, Hannon wondered. How do worried about the availability of safe working parents cope with this UA yet affordable day care, after-school IJ kind of danger and how do the programs, and other after-school ar- children perceive the situation? rangements, even in ostensibly safe, O T Dr. Hannon also knew from her G suburban neighborhoods. How, she research that women were enter- E I wondered, do families manage in areas From Page 19 ing the workforce in Northern D n that are inherently unsafe? Although his or her individual work that would later feed the screens, and free local beer. -

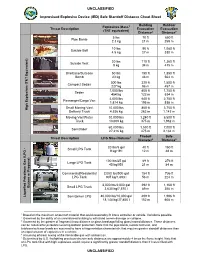

Improvised Explosive Device (IED) Safe Standoff Distance Cheat Sheet

UNCLASSIFIED Improvised Explosive Device (IED) Safe Standoff Distance Cheat Sheet Building Outdoor Explosives Mass1 Threat Description Evacuation Evacuation (TNT equivalent) Distance2 Distance3 5 lbs 70 ft 850 ft Pipe Bomb 2.3 kg 21 m 259 m 10 lbs 90 ft 1,080 ft Suicide Belt 4.5 kg 27 m 330 m 20 lbs 110 ft 1,360 ft Suicide Vest 9 kg 34 m 415 m Briefcase/Suitcase 50 lbs 150 ft 1,850 ft Bomb 23 kg 46 m 564 m 500 lbs 320 ft 1,500 ft Compact Sedan 227 kg 98 m 457 m 1,000 lbs 400 ft 1,750 ft Sedan 454 kg 122 m 534 m 4,000 lbs 640 ft 2,750 ft Passenger/Cargo Van 1,814 kg 195 m 838 m Small Moving Van/ 10,000 lbs 860 ft 3,750 ft High Explosives (TNT Equivalent) Delivery Truck 4,536 kg 263 m 1,143 m Moving Van/Water 30,000 lbs 1,240 ft 6,500 ft Truck 13,608 kg 375 m 1,982 m 60,000 lbs 1,570 ft 7,000 ft Semitrailer 27,216 kg 475 m 2,134 m Fireball Safe Threat Description LPG Mass/Volume1 Diameter4 Distance5 20 lbs/5 gal 40 ft 160 ft - Small LPG Tank 9 kg/19 l 12 m 48 m 100 lbs/25 gal 69 ft 276 ft Large LPG Tank 45 kg/95 l 21 m 84 m Commercial/Residential 2,000 lbs/500 gal 184 ft 736 ft LPG Tank 907 kg/1,893 l 56 m 224 m 8,000 lbs/2,000 gal 292 ft 1,168 ft Butane or Propane) Small LPG Truck 3,630 kg/7,570 l 89 m 356 m Liquefied Petroleum Gas (LPG Semitanker LPG 40,000 lbs/10,000 gal 499 ft 1,996 ft 18,144 kg/37,850 l 152 m 608 m 1 Based on the maximum amount of material that could reasonably fit into a container or vehicle.