Open Call and Food Systems Planning Papers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Key Officers List (UNCLASSIFIED)

United States Department of State Telephone Directory This customized report includes the following section(s): Key Officers List (UNCLASSIFIED) 9/13/2021 Provided by Global Information Services, A/GIS Cover UNCLASSIFIED Key Officers of Foreign Service Posts Afghanistan FMO Inna Rotenberg ICASS Chair CDR David Millner IMO Cem Asci KABUL (E) Great Massoud Road, (VoIP, US-based) 301-490-1042, Fax No working Fax, INMARSAT Tel 011-873-761-837-725, ISO Aaron Smith Workweek: Saturday - Thursday 0800-1630, Website: https://af.usembassy.gov/ Algeria Officer Name DCM OMS Melisa Woolfolk ALGIERS (E) 5, Chemin Cheikh Bachir Ibrahimi, +213 (770) 08- ALT DIR Tina Dooley-Jones 2000, Fax +213 (23) 47-1781, Workweek: Sun - Thurs 08:00-17:00, CM OMS Bonnie Anglov Website: https://dz.usembassy.gov/ Co-CLO Lilliana Gonzalez Officer Name FM Michael Itinger DCM OMS Allie Hutton HRO Geoff Nyhart FCS Michele Smith INL Patrick Tanimura FM David Treleaven LEGAT James Bolden HRO TDY Ellen Langston MGT Ben Dille MGT Kristin Rockwood POL/ECON Richard Reiter MLO/ODC Andrew Bergman SDO/DATT COL Erik Bauer POL/ECON Roselyn Ramos TREAS Julie Malec SDO/DATT Christopher D'Amico AMB Chargé Ross L Wilson AMB Chargé Gautam Rana CG Ben Ousley Naseman CON Jeffrey Gringer DCM Ian McCary DCM Acting DCM Eric Barbee PAO Daniel Mattern PAO Eric Barbee GSO GSO William Hunt GSO TDY Neil Richter RSO Fernando Matus RSO Gregg Geerdes CLO Christine Peterson AGR Justina Torry DEA Edward (Joe) Kipp CLO Ikram McRiffey FMO Maureen Danzot FMO Aamer Khan IMO Jaime Scarpatti ICASS Chair Jeffrey Gringer IMO Daniel Sweet Albania Angola TIRANA (E) Rruga Stavro Vinjau 14, +355-4-224-7285, Fax +355-4- 223-2222, Workweek: Monday-Friday, 8:00am-4:30 pm. -

Building on Nature: Area-Based Conservation As a Key Tool for Delivering Sdgs

Area-based conservation as a key tool for delivering SDGs CITATION For the publication: Kettunen, M., Dudley, N., Gorricho, J., Hickey, V., Krueger, L., MacKinnon, K., Oglethorpe, J., Paxton, M., Robinson, J.G., and Sekhran, N. 2021. Building on Nature: Area-based conservation as a key tool for delivering SDGs. IEEP, IUCN WCPA, The Nature Conservancy, The World Bank, UNDP, Wildlife Conservation Society and WWF. For individual case studies: Case study authors. 2021. Case study name. In: Kettunen, M., Dudley, N., Gorricho, J., Hickey, V., Krueger, L., MacKinnon, K., Oglethorpe, J., Paxton, M., Robinson, J.G., and Sekhran, N. 2021. Building on Nature: Area-based conservation as a key tool for delivering SDGs. IEEP, IUCN WCPA, The Nature Conservancy, The World Bank, UNDP, Wildlife Conservation Society and WWF. CORRESPONDING AUTHORS Nigel Dudley ([email protected]) and Marianne Kettunen ([email protected]) PARTNERS Institute for European Environmental Policy (IEEP) IUCN World Commission on Protected Areas (WCPA) The Nature Conservancy (TNC) The World Bank Group UN Development Programme (UNDP) Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) WWF DISCLAIMER The information and views set out in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect official opinions of the institutions involved. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This report and the work underpinning it has benefitted from the support of the following people: Sophia Burke (AmbioTEK CIC), Andrea Egan (UNDP), Marie Fischborn (PANORAMA), Barney Long (Re-Wild), Melanie McField (Healthy Reefs), Mark Mulligan (King’s College, London), Caroline Snow (proofreading), Sue Stolton (Equilibrium Research), Lauren Wenzel (NOAA), and from the many case study authors named individually throughout the publication. -

GALLATIN COUNTY UNCLAIMED PROPERTY <

GALLATIN COUNTY UNCLAIMED PROPERTY < $50 DEPT PAYEE LAST KNOWN ADDRESS CITY ST ZIP CHECK $ TREASURER 191 LLC 2001 STADIUM DR BOZEMAN MT 59715 $6.60 TREASURER 2575 LLC 2510 WARREN AVE CHEYENNE MT 82001 $6.60 TREASURER 4 BOYS HOLDING CO 101 PINE AVE ANNA MARIA FL 34216 $6.60 TREASURER 4 THIRD ST LLC 5645 RAMSHORN ST GALLATIN GATEWAY MT 59730 $6.60 C OF DC A LA CARTE $20.15 DETENTION AAFEDT, MICAH 10636 COTTONWOOD RD BOZEMAN MT 59718 $5.32 C OF DC ABATE, GRACE 216 WESTRIDGE DR BOZEMAN MT 59715 $16.36 AUDITOR ABC RENTAL & EQUIPMENT SALES 80 SHIRE TRAIL BOZEMAN MT 59718 $40.00 JUSTICE CT ABC RENTAL & EQUIPMENT SALES 80 SHIRE TRAIL BOZEMAN MT 59718 $20.51 TREASURER ABERAJESS LLC 6 NORTH VILLAGE DR SW #107 OCEAN SHORES WA 98569 $7.21 C OF DC ABNEY, LARRY ROGER 93 CEDAR SHADE LANE BOZEMAN MT 59718 $23.99 DETENTION ABRAHAM, JENNIFER $0.20 DETENTION ACERRA, RICHARD $5.00 C OF DC ACHESON, JOHN 317 WILDA LANE BOZEMAN MT 59718 $12.00 TREASURER ACKERMAN, BRENDA 322 MOON BEAM LN BELGRADE MT 59714 $12.00 DETENTION ACORD, SHANE $5.00 DETENTION ACOSTA, ANDRE $9.00 DETENTION ACRES, THOMAS $3.00 JUSTICE CT ACTION PAWN 625 N 7TH BOZEMAN MT 59715 $4.12 AUDITOR ADAMEK, SCOTT $16.68 DETENTION ADAMS, CASEY $9.00 DETENTION ADAMS, JENNIFER $0.21 DETENTION ADAMS, NICHOLAS $4.90 TREASURER ADAMS, RUTH PO BOX 2783 STONEY PLAIN AB T721Y3 $6.00 DETENTION ADAMS, SHALYN $1.00 C OF DC ADAMSON, JACOB 6700 TELEPHONE ROAD VENTURA CA 93001 $0.45 DETENTION ADAMSON, STEPHEN $21.00 C OF DC ADELMAN, JACOB SCOTT 2202 ARROWLEAF HILLS BOZEMAN MT 59715 $17.00 DETENTION ADKINS, COLTER $10.00 AUDITOR AGUILAR, TRACIE L 110 BENNETTE DRIVE BOZEMAN MT 59715 $9.20 AUDITOR AGUILAR, TRACIE L. -

Candidates for Degrees

CANDIDATES FOR DEGREES Doctoral Degrees COLLEGE OF AGRICULTURE Doctor of Philosophy in Ecology and Environmental Sciences Alexander Bryce Olson Michaud Advisor: John Priscu, Ph.D. Dissertation Title: Microbially Mediated Biogeochemical Cycles in Polar Ice Covered Lakes Pamela Santibanez Avila Advisor: John Priscu, Ph.D. Dissertation Title: Factors Influencing the Abundance of Microorganisms in Icy Environments Heidi Jean Smith Advisor: Christine Foreman, Ph.D. Dissertation Title: Microbial Community Composition and the Transformation of Dissolved Organic Matter in Supraglacial Environments Kimberley T. Taylor Advisor: Bruce Maxwell, Ph.D. Dissertation Title: Drivers, Impacts & Feedback of Global Pinus Contorta (Lodgepole Pine) Invasions Trista Juliana Vick-Majors Advisor: John Priscu, Ph.D. Dissertation Title: Biogeochemical Processes in Antarctic Aquatic Environments: Linkages & Limitations Doctor of Philosophy in Plant Science Andrea Correa Varella Advisor: Luther Talbert, Ph.D. Dissertation Title: Genetic Basis of Wheat Resistance to the Wheat Stem Sawfly COLLEGE OF EDUCATION, HEALTH AND HUMAN DEVELOPMENT Doctor of Philosophy in Education Mary E. Ulrich Advisor: Carrie Myers, Ph.D. Dissertation Title: Learning Relational Ways of Being: What Globally Engaged Scholars Have Learned about Global Engagement and Sustainable Community Development 7 Doctor of Education Anne Klees Zulick Milkovich Advisor: Carrie Myers, Ph.D. Dissertation Title: Institutional Performance Management: A Model of Integrated Planning Natalie Boren Miller Advisor: Arthur Bangert, Ed.D. Dissertation Title: Administrators’ & Teachers’ Perceptions of the Formative Assessment Process Used to Evaluate Students’ Level of Proficiency & Ongoing Instruction in Reading Lynne Scaffidi Scalia Advisor: Tena Versland, Ed.D. Dissertation Title: Derailed: Factors Influencing College & Career Decisions of High School Students in a De-Industrialized Rural Community Kathryn D. -

1056 T CELLS and AGING, JANUARY 2002 UPDATE Graham

[Frontiers in Bioscience 7, d1056-1183, May 1, 2002] T CELLS AND AGING, JANUARY 2002 UPDATE Graham Pawelec1, Yvonne Barnett2, Ros Forsey3, Daniela Frasca4, Amiela Globerson5, Julie McLeod6, Calogero Caruso7, Claudio Franceschi8, Támás Fülöp9, Sudhir Gupta10, Erminia Mariani8, Eugenio Mocchegiani11, Rafael Solana12 1University of Tübingen, Center for Medical Research, ZMF, Waldhörnlestr. 22, D-72072 Tübingen, Germany, 2 University of Ulster, Coleraine, UK, 3 Unilever Research, Bedford, UK, 4 University of Miami, FL, 5 University of the Negev, Israel, 6 University of the West of England, Bristol, UK, 7 University of Palermo, Italy, 8 University of Bologna, Italy, 9 University of Sherbrooke, Quebec, Canada, 10 University of California, Irvine, CA, 11 INRCA, Ancona, Italy, 12 University of Córdoba, Spain TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Abstract 2. Introduction: How do we establish whether immunosenescence exists and if so whether it means anything to immunological defence mechanisms in aging? 3. Factors contributing to immunosenescence 3.1. Hematopoiesis 3.2. Thymus 4. Post-thymic aging 4.1. T cell subsets 4.2. T cell repertoire 4.3. T cell function 4.3.1. Accessory cells 4.3.2. T cell receptor signal transduction 4.3.3. Costimulatory pathways 4.3.3.1. CD28 family coreceptors and CD80 family ligands 4.3.3.2. Other costimulators 4.4. Cytokine production and response 4.4.1. Regulation of gene transcription 4.4.2. Cytokine secretion 4.4.3. Confounding factors affecting cytokine secretion results 4.4.4. Levels of cytokines in plasma 4.4.5. Cytokine antagonists 4.4.6. Cytokine receptor expression 5. Clonal expansion after T cell activation 5.1. -

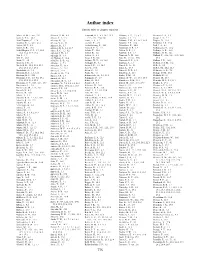

Author Index

Author index Entries refer to chapter number Aalten, D. M. F. van, 21.1 Allinson, N. M., 8.1 Artymiuk, P. J., 4.3, 20.2, 21.1, Baldwin, E. T., 1.3, 4.1 Beevers, C. A., 1.2 Aarts, E. H. L., 18.2 Allison, T. J., 1.3 22.2, 23.1, 23.4, 26.1 Baldwin, J. J., 1.3 Beggs, J. D., 3.1 Abad-Zapatero, C., 13.4 Allocati, N., 1.3 Arvai, A. S., 1.3 Baldwin, J. M., 4.2, 19.2, 19.6 Beglov, D., 23.4 Abagyan, R. A., 21.1, 21.2 Allured, V. S., 1.3 Ascenzi, P., 23.1 Baldwin, J. P., 19.4 Beintema, J. J., 13.4 Abbate, M. J., 6.2 Almassy, R., 1.3 Aschaffenburg, R., 26.1 Balendiran, K., 24.4 Bell, J. A., 4.3 Abbey, C. K., 19.6 Almassy, R. J., 1.3, 19.3 Ashford, V. A., 1.3 Ballantine, S. P., 1.3 Bellamacina, C., 23.4 Abdel-Meguid, S. S., 1.3, 10.2, Almo, S. C., 1.3, 8.2 Ashida, T., 22.4 Ballou, D. P., 1.3 Bellamy, A. R., 19.6 11.2, 11.4, 11.5, 13.4 Almond, J. W., 1.3 Ashraf, K., 16.1 Bamblin, S. J., 1.3 Bellamy, H. D., 10.1 Abe, S., 1.3 Alpaugh, M., 1.3 Ashton, A., 9.1 Bamford, D. H., 19.6 Bellard, S., 18.4, 21.1, 21.2, 24.2, Abe, Y., 21.2 Als-Nielsen, J., 14.2 Assaf, J. -

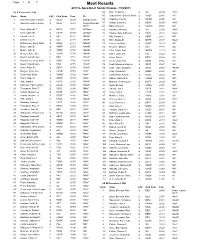

Meet Results

Page 1 of 21 Meet Results 2011 IL Speedo LC Senior Champ - 7/14/2011 50 F Freestyle LCM 64 Park, Christina J IL GA 28.99 "AAA" Rank Name LSC Club Code Time TS 65 Schumacher, Danielle Marie IL HOSC 29.01 "AA" 1 Swenson, Evan Carolyn IL WILD 26.39 Olympic Trials 66 Kopylova, Ksenia IL SWAQ 29.02 "AA" 2 Swenson, Evan Carolyn IL WILD 26.88 Winter Nationals 67 Grasty, Jessica L IL BDSC 29.05 "AAA" (SCY) 68 Miller, Nicole E IL PAWW 29.07 "AA" 3 Sims, Gabrielle T IL EXPR 27.17 US Open 69 Doolan, Colleen E IL GA 29.08 "AAA" 4 Sims, Gabrielle T IL EXPR 27.29 US Open 70 Snyder, Mary Catherine IL SCST 29.10 "AAA" 5 Larsen, Tori M IL EST 27.37 "AAAA" 71 Hill, Jennifer C IL HEAT 29.15 "AA" 6 Larsen, Tori M IL EST 27.38 "AAAA" 72 Ricci, Elaina M IL EXPR 29.17 "AAA" 7 Braunecker, Avery Marie IL SUSA 27.43 "AAAA" 73 Licari, Lisa Marie IL SCST 29.18 "AA" 8 Munro, Jane E IL YWFF 27.53 "AAAA" 74 Brearton, Maia A IL SCT 29.20 "AA" 9 Munro, Jane E IL YWFF 27.55 "AAAA" 75 Lifka, Taylor Ann IL WHTN 29.23 "AA" 10 Merges, Rylee Sue IL ACAD 27.58 "AAAA" 76 Roller, Julia Ann IL UN 29.24 "AA" 11 Boyd, Hannah Lynn IL RED 27.61 "AAAA" 76 Sivak, Erin K IL BRRY 29.24 "AA" 12 Braunecker, Avery Marie IL SUSA 27.66 "AAAA" 78 Licari, Laura Ann IL SCST 29.26 "AA" 13 Boyd, Hannah Lynn IL RED 27.75 "AAAA" 79 Scott, Michaela Marjorie IL SCST 29.27 "AA" 14 Wells, Paige N IL BDSC 27.76 "AAAA" 79 Kolar, Jamie Susanne IL WILD 29.27 "AAAA" 15 Merges, Rylee Sue IL ACAD 27.88 "AAA" 81 Gray, Courtney L IL RMSC 29.28 "AA" 16 Scott, Mary Edan IL SWAQ 27.92 "AAA" 81 Golembeski, Keri M -

Nummer 33/17 18 Augustus 2017 Nummer 33/17 2 18 Augustus 2017

Nummer 33/17 18 augustus 2017 Nummer 33/17 2 18 augustus 2017 Inleiding Introduction Hoofdblad Patent Bulletin Het Blad de Industriële Eigendom verschijnt The Patent Bulletin appears on the 3rd working op de derde werkdag van een week. Indien day of each week. If the Netherlands Patent Office Octrooicentrum Nederland op deze dag is is closed to the public on the above mentioned gesloten, wordt de verschijningsdag van het blad day, the date of issue of the Bulletin is the first verschoven naar de eerstvolgende werkdag, working day thereafter, on which the Office is waarop Octrooicentrum Nederland is geopend. Het open. Each issue of the Bulletin consists of 14 blad verschijnt alleen in elektronische vorm. Elk headings. nummer van het blad bestaat uit 14 rubrieken. Bijblad Official Journal Verschijnt vier keer per jaar (januari, april, juli, Appears four times a year (January, April, July, oktober) in elektronische vorm via www.rvo.nl/ October) in electronic form on the www.rvo.nl/ octrooien. Het Bijblad bevat officiële mededelingen octrooien. The Official Journal contains en andere wetenswaardigheden waarmee announcements and other things worth knowing Octrooicentrum Nederland en zijn klanten te for the benefit of the Netherlands Patent Office and maken hebben. its customers. Abonnementsprijzen per (kalender)jaar: Subscription rates per calendar year: Hoofdblad en Bijblad: verschijnt gratis Patent Bulletin and Official Journal: free of in elektronische vorm op de website van charge in electronic form on the website of the Octrooicentrum -

2016–17 Commencement Program

COMMENCEMENT UNIVERSITY OF COLORADO BOULDER FOLSOM STADIUM MAY 12, 2017 One Hundred Forty-First Year of the University CommCoverMay2017 update.indd 1 3/23/17 11:01 AM Norlin Charge to the Graduates The first commencement at the University of Colorado was held for six graduates on June 8, 1882, in the chapel of Old Main. It was not until 40 years later, on September 4, 1922, that the first summer commencement was held. Since the first commencement in 1882, the University of Colorado Boulder has awarded 350,000 degrees. The traditional Norlin Charge to the graduates was first read by President George Norlin to the June 1935 graduating class. You are now certified to the world at large as alumni of the university. She is your kindly mother and you her cherished sons and daughters. This exercise denotes not your severance from her, but your union with her. Commencement does not mean, as many wrongly think, the breaking of ties and the beginning of life apart. Rather it marks your initiation in the fullest sense into the fellowship of the university, as bearers of her torch, as centers of her influence, as promoters of her spirit. The university is not the campus, not the buildings on campus, not the faculties, not the students of any one time—not one of these or all of them. The university consists of all who come into and go forth from her halls, who are touched by her influence, and who carry on her spirit. Wherever you go, the university goes with you. -

Spring 2018 • May 6, 2018 • 12 P.M

POMP, CIRCUMSTANCE, AND OTHER SONGS OF A LIFETIME POMP, CIRCUMSTANCE, (continued from inside front cover) AND OTHER SONGS OF A LIFETIME —by Professor David Citino, 1947–2005, Late University Poet Laureate I say, rather, the richness of us, were it not for the lullabyes and songs (Originally presented as the 2000 Winter Commencement address) of dear parents, their parents, theirs. of selves that balance this globe Some are here today in the flesh. and enable it to spin true. Grandson Many are not. We mourn them with cadences of peasant immigrants, I was given of our hearts. Think how many people If you’re like me, you’ve got a big head, the opportunity to earn a doctorate sang before us, gave us a name, a voice, not to mention a funny robe, full of music— to do your best. Tennessee Ernie Ford, in English literature from Ohio State— taught us the right words. We must poems and melodies, the tunes “Sixteen Tons”: St. Peter don’t you because my family labored long nights cherish them by remembering every song. we move to, shower and shave by, call me ‘Cause I can’t go. I owe around the kitchen table trying to learn When we sing to others, we honor study, write to. Not just the incidental, my soul to the company store. this arduous English. I sat where our fathers and mothers, thank them but the momentous music keeping time. You have been digging deep in mines you’re sitting twenty-six years ago. for this day of profound scarlet and gray Our histories are measures of song. -

Publikationsbericht 2004 Publikationsbericht 2004: Otto-Von-Guericke-Universität Magdeburg

Publikationsbericht 2004 Publikationsbericht 2004: Otto-von-Guericke-Universität Magdeburg Otto-von-Guericke-Universität Magdeburg Universitätsplatz 2 D-39106 Magdeburg Telefon: +49 391 67 01; Telefax: +49 391 67 11156 www.uni-magdeburg.de 1. Leitung Prof. Dr.-Ing. habil. Jens Strackeljan (Rektor) Prof. Dr. rer. nat. Jürgen Christen (Prorektor für Planung und Haushalt) Prof. Dr. rer. nat. Volkmar Leßmann (Prorektor für Forschung, Technologie und Chancengleichheit) Prof. Dr. rer. nat. Franziska Scheffler (Prorektorin für Studium und Lehre) 2. Fakultäten Fakultät für Maschinenbau Fakultät für Verfahrens- und Systemtechnik Fakultät für Elektrotechnik und Informationstechnik Fakultät für Informatik Fakultät für Mathematik Fakultät für Naturwissenschaften Medizinische Fakultät Fakultät für Humanwissenschaften Fakultät für Wirtschaftswissenschaft Publikationsbericht 2004 FAKULTÄT FÜR MASCHINENBAU Universitätsplatz 2, 39106 Magdeburg Tel. +49 (0) 391 67 18519, Fax +49 (0) 391 67 12538 1. Leitung Prof. Dr.-Ing. Karl-Heinrich Grote (Dekan) Prof. Dr. rer. nat. Michael Scheffler (Prodekan) 2. Veröffentlichungen Hochschulschriften Bufka, Dietmar (ext.) Typologisierung von Order-to-Delivery-Prozessen in der Automobilindustrie. 2004, VIII, 193 S. Magdeburg, Univ., Fak. für Maschinenbau, Diss., 2004 Zugl. unter ISBN 3-8167-6693- Habedank, Gabriele (ext.) Neuartige Bearbeitungsverfahren zur Modifizierung senkerodierter Randschichten. 2004, VIII, 197 S. Magdeburg, Univ., Fak. für Maschinenbau, Diss., 2004 Zugl. unter ISBN 3-8322-3626- Hochrainer, Peter (ext.) Projektwirkungscontrolling zur Verbesserung der Implementierungsqualität von Industrieprojekten. 2004, IX, 257 S. Magdeburg, Univ., Fak. für Maschinenbau, Diss., 2004 Jelitto, Christian (ext.) Numerische Auslegung eines neuen Brennverfahrens für Benzin-Direkteinspritzung. 2004, II, 127 S. Magdeburg, Univ., Fak. für Maschinenbau, Diss., 2004 (Stand vom: 20.05.2005) Kersten, Mike (ext.) Prozessmodell zur IT-gestützten Umsetzung Integrierter Managementsysteme. -

SCCGS Quarterly Volume 42 (2019) Surname Index

SCCGS Quarterly Volume 42 (2019) Surname Index To find all instances of your family name, search for variants caused by poor handwriting, misinterpretation of similar letters or their sounds. A few such examples are L for S, c for e, n for u, u for a; phonetic spellings (Aubuchon for Oubuchon); abbreviations (M’ for Mc ); single letters for double (m for mm, n for nn); translations (King for Roy, Carpenter for Zimmermann). Other search tips: substitute each vowel for other ones, search for nicknames, when hyphenated – search for each surname alone, with and without “de” or “von”; with and without a space or apostrophe (Lachance and La Chance, O’Brien and OBRIEN). More suggestions are on the SCCGS website Quarterly pages at https://stclair-ilgs.org/quarterly-surname-index/ ___, blank 42 3 161 ADAMORE 42 4 181 ___, female 42 1 12 ADAMS 42 1 14, 19 ___, male 42 1 12, 24, 29, 30 ADAMS 42 2 58, 85, 97, 104 ___, male 42 2 58, 59, 64, 78, 96 ADAMS 42 3 117, 122, 124, ___, male 42 3 152, 158 128, 140, 156 ___, male 42 4 178 ADAMS 42 4 181, 197, 199, 200, 212, 215, AARON 42 2 105 216 AARON 42 4 199 ADEHARDT 42 4 228 ABANION 42 3 118 ADELHARDT 42 2 87 ABBOTT 42 3 126 ADELSBERGER 42 1 37 ABBOTT 42 4 181 ADER 42 1 40 ABEGG 42 1 13, 21, 37 ADERHOLT 42 4 222 ABEGG 42 3 154 ADKINS 42 3 117 ABEL 42 4 208 ADKINS 42 4 202, 204, 214 ABEND 42 3 152, 157 ADLER 42 1 42 ABENDROTH 42 2 97 ADLER 42 3 147 ABERCROMBIE 42 2 97 ADLER 42 4 181, 182, 224 ABERLE 42 1 17, 25 ADNEY 42 3 118 ABERNATHY 42 3 124, 130 ADOMAITIS 42 2 72 ABERNATHY 42 4 199 ADRIAN 42 3 133 ABLE 42 4 199 ADRIAN 42 4 221, 227, 228 ABNEY 42 3 117 ADULIA 42 1 16 ABRAHAM 42 1 18 AGHETTE 42 1 37 ABSTON 42 4 199 AGLENE 42 4 181 ACCOMANDO 42 4 214 AGLES 42 4 200 ACKER 42 1 13 AGNE 42 2 97, 99, 104 ACKER 42 2 60 AGNE 42 4 203, 205, 228 ACKERMAN 42 4 181 AGNEW 42 4 203 ACKERMANN 42 3 145 AGOSTINI 42 2 97 ACKERMANN 42 4 225 AGUILERA 42 1 37 ACKERS 42 2 79 AHLENT 42 4 199 ACNUFF 42 1 40 AHLERS 42 1 12 ADAIR 42 2 102 AHLERT 42 4 199 ADAM 42 2 97 AHLHEIM 42 2 60 ADAM 42 3 157 St.