Willie Cole's Africa Remix

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hank Willis Thomas

Goodman Gallery Hank Willis Thomas Biography Hank Willis Thomas (b. 1976, New Jersey, United States) is a conceptual artist working primarily with themes related to perspective, identity, commodity, media, and popular culture. Thomas has exhibited throughout the United States and abroad including the International Center of Photography, New York; Guggenheim Museum Bilbao, Spain; Musée du quai Branly, Paris; Hong Kong Arts Centre, Hong Kong, and the Witte de With Center for Contemporary Art, Netherlands. Thomas’ work is included in numerous public collections including the Museum of Modern Art, New York; Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York; Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; Brooklyn Museum, New York; High Museum of Art, Atlanta, and National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C. His collaborative projects include Question Bridge: Black Males, In Search Of The Truth (The Truth Booth), Writing on the Wall, and the artist-run initiative for art and civic engagement For Freedoms, which in 2017 was awarded the ICP Infinity Award for New Media and Online Platform. Thomas is also the recipient of the Gordon Parks Foundation Fellowship (2019), the Guggenheim Foundation Fellowship (2018), Art for Justice Grant (2018), AIMIA | AGO Photography Prize (2017), Soros Equality Fellowship (2017), and is a member of the New York City Public Design Commission. Thomas holds a B.F.A. from New York University (1998) and an M.A./M.F.A. from the California College of the Arts (2004). In 2017, he received honorary doctorates from the Maryland Institute of Art and the Institute for Doctoral Studies in the Visual Arts. Artist Statement Hank Willis Thomas is an American visual photographer whose primary interested are in race, advertising and popular culture. -

African Collection

calendar African Art from the Permanent Collection Collections of the RMCA: January 1, 2005–December 31, 2008 Headdresses Neuberger Museum of Art, SUNY Purchase December 20, 2006–September 30, 2007 Purchase, NY Royal Museum for Central Africa Tervuren, Belgium African Vision: Highlights from the The Walt Disney-Tishman African Art Collection Continuity and Change: February 15, 2007–September 7, 2008 Three Generations of Ethiopian Artists AFRICAN National Museum of African Art May 25–December 8, 2007 Washington, DC Diggs Gallery, Winston-Salem State University Winston-Salem, NC COLLECTION Afrique Noire: Fotografien von Didier Ruef Eternal Ancestors: Made possible by SunTrust Bank April 25– August 19, 2007 The Art of the Central African Reliquary Völkerkunemuseum der Universität Zürich October 2, 2007–March 2, 2008 Downloaded from http://direct.mit.edu/afar/article-pdf/40/3/95/1816128/afar.2007.40.3.95.pdf by guest on 26 September 2021 Zürich, Switzerland Metropolitan Museum of Art New York, NY Anxious Objects: Willie Cole’s Favorite Brands Inscribing Meaning: June 15–September 2, 2007 Writing and Graphic Systems in African Art Frye Art Museum May 9–September 3, 2007 Seattle, WA National Museum of African Art Washington, DC September 26, 2007–January 7, 2008 Cantor Arts Center at Stanford University October 14, 2007–February 17, 2008 Stanford, CA Fowler Museum at UCLA Los Angeles, CA Art of Being Tuareg: Saharan Nomads in a Modern World Meditations on African Art: May 9–August 19, 2007 Color Cantor Arts Center at Stanford University April 18–August 19, 2007 Stanford, CA Baltimore Museum of Art Baltimore, MD Bamako: African Photographers Meditations on African Art: May 18–September 25, 2007 Pattern Museum of the African Diaspora August 29, 2007–January 13, 2008 San Francisco, CA Baltimore Museum of Art Baltimore, MD Benin—Könige und Rituale. -

Finding Aid to the Historymakers ® Video Oral History with Willie Cole

Finding Aid to The HistoryMakers ® Video Oral History with Willie Cole Overview of the Collection Repository: The HistoryMakers®1900 S. Michigan Avenue Chicago, Illinois 60616 [email protected] www.thehistorymakers.com Creator: Cole, Willie, 1955- Title: The HistoryMakers® Video Oral History Interview with Willie Cole, Dates: February 3, 2017 Bulk Dates: 2017 Physical 6 uncompressed MOV digital video files (2:50:03). Description: Abstract: Sculptor Willie Cole (1955 - ) was most known for his found object assemblages, which featured steam irons, high heeled shoes and plastic water bottles. His work addressed themes of domesticity, femininity and racial identity. Cole was interviewed by The HistoryMakers® on February 3, 2017, in Mine Hill, New Jersey. This collection is comprised of the original video footage of the interview. Identification: A2017_053 Language: The interview and records are in English. Biographical Note by The HistoryMakers® Sculptor Willie Cole was born on January 3, 1955 in Somerville, New Jersey. In 1958, he moved to Newark, New Jersey, where he took art classes at the Newark Museum, and later attended the Arts High School of Newark. Cole went on to receive his B.F.A degree from the School of Visual Arts in New York City, New York. He continued his art education by attending classes at the Art Students League of New York. After graduation, Cole worked as a freelance artist and graphic designer. In 1988, he completed his first major art installation, Ten Thousand Mandellas. The installation led to his first major gallery show, which took place at Franklin Furnace Gallery in New York City, New York in 1989. -

Studio in Your House?

BEGIN. Willie Cole, a well-known and leading American sculptor and visual artist, discusses abstract creativity and the spiritual relationship between art and artist. Can you explain your first experiences with African art? My first experience was at the Newark Museum. They had a huge piece there, as soon as you walked through the front door. I think it was called ‘the Nimba.’ Although at the time, I was feeling the whole museum so that piece didn’t jump out to me in any special way. It was my first time in a museum. More than when I was a little kid, I think my greatest reception of African art came when I was in college, when I studied African art. OK MR. COLE. AND LELAN YUNG TOBIAS JON HITTEL, NATALIE BY INTERVIEW AND ALEX BOARDWINE SHANICE AGA BY PHOTOGRAPHS How did your college experience inspire what you create now? I went to the School of Visual Arts in New York, and at that time, even though it was a hippy school, it was the best art school in the country. I had Chuck Close for painting, and Jonathan Borofsky for sculpture. They were all professionals working as freelancers. And the school had a motto, two mottos really. One was, ‘What good is a talent if you don’t know what to do with it?’ The other one was, ‘Our times call for multiple careers,’ which meant that if you have a talent, your talent is not just the physical thing you create; it’s the way that you think about things. -

Anne Klein with a Baby in Transit Willie Cole, 2009 2009.57 Sculpture

Anne Klein with a Baby in Transit Willie Cole, 2009 2009.57 Sculpture: shoes, washers, wires, screws Not on view, on loan. Biography Willie Cole was born in 1955 in Newark, NJ. He received his BA in Fine Arts from the NY School of Visual Arts and continued his studies at the Art Students League of New York. Cole was the first winner of the David C. Driskell Prize established by the High Museum of Atlanta to honor and celebrate African American art and art history. Cole's work is found in private collections and major museums. Says Cole, “I think that when one culture is dominated by another culture, the energy or powers or gods of the previous culture hide in the vehicles of the new cultures. I think the spirit of Shango (Yoruba god of thunder and lightning) is a force hidden in the iron because of the fire, and the power of Ogun--his element is iron--is also hidden in these metal objects.” Cole lives and works near Newark, NJ. Artist's inspiration and place in contemporary art "Willie Cole’s art is best known for assembling and transforming ordinary domestic and used objects such as irons, ironing boards, high-heeled shoes, hair dryers, bicycle parts, wooden matches, lawn jockeys, and other discarded appliances and hardware, into imaginative and powerful works of art and installations. Through the repetitive use of single objects in multiples, Cole’s assembled sculptures acquire a transcending and renewed metaphorical meaning, or become a critique of our consumer culture. Cole’s work is generally discussed in the context of postmodern eclecticism, combining references and appropriation ranging from African and African American imagery, to Dada’s readymades and Surrealism’s transformed objects, and icons of American pop culture or African and Asian masks, into highly original and witty assemblages.". -

Willie Cole's Black Art Matters

Willie Cole’s Black Art Matters Black Art Matters is an affirmation of the importance and presence of Black Art socially, academically, culturally, and institutionally. It both teaches and celebrates the Black artist’s contribution to the human experience. Join the Movement. SAVING LIVES 10% of the proceeds from the sale of Willie Cole’s Black Art Matters Merchandise are donated to Wells Bring Hope whose mission is saving lives with safe water. Learn more and donate at wellsbringhope.org Willie Cole’s art is in the permanent collection of major museums including The Metropolitan Museum of Art, NYC; High Museum of Art, Atlanta; National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC; The Museum of Modern Art, NYC; The Newark Museum of Art, Newark. T-Shirts Hoodies SCTEE-28428-SM - Small SCTEE-28428-XL - Extra Large SCHD-28428-SM - Small SCHD-28428-XL - Extra Large SCTEE-28428-MD - Medium SCTEE-28428-XXL - XX Large SCHD-28428-MD - Medium SCHD-28428-XXL - XX Large SCTEE-28428-LG - Large All Sizes $12.50 each - 3 min. (per size) SCHD-28428-LG - Large All Sizes $31.50 each - 3 min. (per size) 2.5 x 3.5 Magnet 2 x 3.5 Sticker 1.5" Button Pack BS-28428 2535-28428 15-28428 $1.50 ea. - 12 MOQ $2.25 ea. - 5 MOQ $4.50 ea. - 20 MOQ WEB www.popcornposters.com EMAIL [email protected] TEL 860.610.0000 FAX 860.760.6188 MAIL 1 Cherry St, East Hartford, CT 06108 Willie Cole’s Black Art Matters Mugs Camp Mug Shot Glass CMG-28428 11 oz. -

WILLIE COLE CV Oct 2013

WILLIE COLE 1955 Born in Somerville, New Jersey, lives and works in Mine Hill, NJ 1976 BFA, The School of Visual Arts, New York 1976-79 The Art Students League, New York SELECTED AWARDS & RESIDENCIES 2006 David C. Driskell Prize, High Museum of Art, Atlanta 2002 The Augustus Saint-Gaudens Memorial Fellowship 2000 Artist-in-residence, John Michael Kohler Arts Center Arts/Industry Program, Sheboygan, Wisconsin 1996 Joan Mitchell Foundation Award 1995 The Louis Comfort Tiffany Foundation Grant 1991 The Penny McCall Foundation Grant SELECTED ONE-PERSON EXHIBITIONS 2013-14 Complex Conversations: Willie Cole Sculptures and Wall Works, Albertine Monroe- Brown Gallery, Western Michigan University, Kalamazoo; Weatherspoon Art Museum, University of North Carolina at Greensboro; The College of Wooster Art Museum, Ebert Art Center, Wooster, OH; Faulconer Gallery, Grinnell College, Grinnell, IA; Houghton College, NY 2013 FIRE/FLY, beta pictoris gallery / Maus Contemporary, Birmingham, Alabama If Wishes Were Horses..., Alexander and Bonin, New York From Water to Light, Prospect Street Firestation Gallery, Newark E Pluribus Unum, Grounds for Sculpture, Hamilton, NJ 2012 Deep Impressions: Willie Cole Works on Paper and Sculpture, Rowan University Art Gallery, Glassboro, NJ 2011 GOOD OLD DAYS, beta pictoris gallery / Maus Contemporary, Birmingham, Alabama 2010 Deep Impressions: Willie Cole Works on Paper, The James Gallery, The City University of New York; Memphis Brooks Museum of Art, Memphis; Sarah Moody Gallery of Art, University of Alabama, Tuscaloosa, Alabama 2010 Willie Cole, The College Art Gallery at the College of New Jersey, Ewing POST BLACK AND BLUE, Alexander and Bonin, New York 2007 Living Room, Finesilver Gallery, Houston 2006-08 Anxious Objects: Willie Cole’s Favorite Brands, Montclair Art Museum, New Jersey; Sheldon Memorial Art Museum, Lincoln, Nebraska; Memorial Art Gallery, Rochester, New York; Birmingham Museum of Art, Alabama; Frye Art Museum, Seattle; Stanford University, Iris & B. -

![New Concepts in Printmaking 2, Willie Cole [Wendy Weitman]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7658/new-concepts-in-printmaking-2-willie-cole-wendy-weitman-6007658.webp)

New Concepts in Printmaking 2, Willie Cole [Wendy Weitman]

New concepts in printmaking 2, Willie Cole [Wendy Weitman] Author Cole, Willie, 1955- Date 1998 Publisher The Museum of Modern Art, Department of Prints and Illustrated Books Exhibition URL www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/210 The Museum of Modern Art's exhibition history— from our founding in 1929 to the present—is available online. It includes exhibition catalogues, primary documents, installation views, and an index of participating artists. MoMA © 2017 The Museum of Modern Art NewConcepts in Printmaking2 Willie Cole Ibe Mu>eum ol Modern Art Library, sumsen(*\ BEAC.H C*«RAL NoR.ei.Co & SUNBCftfn STCfliri- PROt TOP, 5|LE\ EUCTRt<. v^- /-yf A( 'r'" ' New Concepts in Printmaking 2: Willie Cole everyday life. Robert Rauschenberghad a friend drive a Will ie Cole constructs his assemblage sculptures from car onto outstretched paper to create his twenty-foot found domestic objects and imbues them with spiritual, Tire Print of 1951. The Nouveau Realiste artist Arman and often mythical, power through allusion and metaphor. printed found rubber stamps in allover compositions and Since the mid-1980s, he has been preoccupied with the later flung paint-dipped household objects onto paper 2 steam iron as a domestic, symbolic, and artistic object. and canvasto create imprints. Several others, including Cole first assembled used irons into iconic figurative Jasper Johns and Yves Klein, used the oiled or painted 3 forms reminiscent of African art. In exploring ways to human body to make impressions. Contemporary artists infuse these unpretentious figures with the potency of have continued to work in this way. Donald Judd's early their progenitors, Cole discovered the scorch. -

Hank Willis Thomas B. 1976- Born in Plainfield, NJ Lives and Works in New York, NY

Hank Willis Thomas b. 1976- Born in Plainfield, NJ Lives and works in New York, NY Education 2017 Honorary PhD, Institute for Doctorial Studies in Visual Arts, Portland, ME 2004 MFA, Photography and MA, Visual Criticism, California College of the Arts, San Francisco, CA 1998 BFA, Photography & African Studies, New York University, New York, NY Selected Solo Exhibition 2021 The Gun Violence Memorial Project, National Building Museum, Washington, D.C. 2020 Forth Bluff, Fourth Bluff Park, Tri-Star Arts, Memphis, TN Hank Willis Thomas: All Things Being Equal..., Crystal Bridges Museum of Art, Bentonville, AR 2020: Action, Freedom, Patriotism, Cornell Fine Arts Museum, Rollins College, Winter Park, FL An All Colored Cast, Kayne Griffin Corcoran, Los Angeles, CA 2019 Hank Willis Thomas: All Things Being Equal..., Portland Art Museum, Portland, OR Exodusters, The Gordon Parks Foundation, Pleasantville, NY Hank Willis Thomas: Unbranded, Abroms-Engel Institute for the Visual Arts, The University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL 2018 What We Ask is Simple, Jack Shainman Gallery, New York, NY Hank Willis Thomas: What We Ask Is Simple, Harvey B. Gantt Center for African-American Arts + Culture, Charlotte, NC Overtime, Cairns Art Gallery, Cairns City, Australia My Life is Ours, Ben Brown Fine Arts, Hong Kong, China Black Survival Guide: or How to Live through a Police Riot, Delaware Art Museum, Wilmington, DE Hank Willis Thomas: Unbranded, Block Museum of Art, Northwestern University, Evanston, IL Hank Willis Thomas: Branded/Unbranded, The -

Gallery Guide

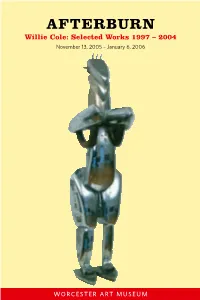

AFTERBURN Willie Cole: Selected Works 1997 – 2004 November 13, 2005 – January 6, 2006 WORCESTER ART MUSEUM Speedster tji wara, 2002, bicycle parts, 188 x 38 x 56/5 cm. Antelope Headdresses (tji wara), Mali, Bamana people, 20th c., Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, New York, Sarah Norton wood, metal. Male, H. 92.7 cm; Museum of African Art, Goodyear Fund. Photo: Bill Orcutt, courtesy Alexander and Rhode Island School of Design, Anonymous gift. Photo: Bonin, New York Eric Gould AFTERBURN Willie Cole: Selected Works 1997 – 2004 Multi-tasking with Willie Cole the Americas. Irons and ironing boards evoke Willie Cole’s work suggests a post-modern the role of many African-American women as eclecticism—combining references, both domestic workers in other peoples’ homes. intended and serendipitous, to the appropria- Scorch marks suggest branding, and the inter- tion of African forms by modern artists, to twined histories of slavery and plantation Dada’s ready-mades and Surrealism’s trans- culture that marked early economic develop- formed objects as well as to icons of American ment in Latin America, the Caribbean and the pop culture. He invests his forms with meaning southern United States. The shape of the iron and history both personal and communal— itself suggests boats, and thus the iniquitous although he might say, he rediscovers meaning Middle Passage where so many died in their that is already present.1 Like other African- forced move from Africa. Visual puns and American artists, Cole personally has mined a verbal play characterize his work, creating the vein of imagery and significance that draws layered meanings that demand our intellectual upon Africa and the experience of Africans in multi-tasking. -

Willie Cole, Wayne Charles Roth and Kiyomi Baird

Seeing Space is an exhibit of the work of three art- ists, Willie Cole, Wayne Charles Roth and Kiyomi Baird. Though this is the tenth exhibit at Gallery at 14 Maple, it is the first invitational show in which members of the Exhibition Committee of Morris Arts and the Geraldine R. Dodge Foundation selected these artists specifically for the high quality of their work and for their imaginative treatment and interpretation of space. Space can be as mundane as the comfortable distance between two people, face- to-face talking. Or as territorial as, “You’re in my space.” And then there are tight spaces, confined, uncomfortable and stressful and those that are generous, spa- cious and expansive. Today, computers run out of space in their memory. Hu- mans do too. Space, like air, (for most people) is taken for granted but is an essen- tial ingredient in our lives. While others still argue about the beginning, i.e. “Which came first, the chicken or egg?” There is no doubt that space, in all of it manifestations, grand and minute, preceded the philosophers, physicists, astronomers, cosmologists, theorists, me- chanical engineers, writers, metaphysicians, mathematicians, artists and musi- cians. Space was there first. But over the millennia, these individuals have used space to describe, postulate, explain, illustrate and demonstrate their theories. From Aristotle to Euclid, from Leibniz to Newton to Kant and Einstein, space and the universe have held the attention of the great thinkers, always. Space can be both ephemeral and permanent--yet ever changing. It has been described as an entity, a relationship between entities or part of a conceptual framework. -

SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2017 Willie Cole: On-Site, Museum of Art, University of New Hampshire (Traveling); Arthur Ross Gallery, Philadelphia, PA

WILLIE COLE b. 1955 Somerville, NJ Lives and works in Mine Hill, NJ EDUCATION 1979 The Art Students League, New York, NY 1976 BA The School of Visual Arts, New York, NY RESIDENCIES 2000 Artist-in-residence, John Michael Kohler Arts Center Arts/Industry Program, Sheboygan, WI 1995 Artist-in-residence, Capp Street Project, San Francisco, CA 1994 Artist-in-residence, Pilchuck Glass School, Seattle, WA Artist-in-residence, The Contemporary, Baltimore, MD 1989 Artist-in-residence, The Studio Museum in Harlem, New York, NY SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2017 Willie Cole: On-Site, Museum of Art, University of New Hampshire (traveling); Arthur Ross Gallery, Philadelphia, PA 2016 Willie Cole: On-Site, David C. Driskell Center, University of Maryland (traveling) 2015 Willie Cole: Aquaphallic, 808 Gallery, Boston University, Boston, MA Willie Cole, Mazmanian Gallery, Framingham State University, Framingham, MA Flawlessly Feminine, Women Who Graced the Cover and Works by Willie Cole, The Diggs Gallery of Winston-Salem State University, Salem, MA Willie Cole: Transformations, Abroms-Engel Institute for the Visual Arts, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL 2014 Complex Conversations: Willie Cole Sculptures and Wall Works The College of Wooster Art Museum, Ebert Art Center, Wooster, OH (traveling); Faulconer Gallery, Grinnell College, Grinnell, IA; Houghton College, NY 2013 Complex Conversations: Willie Cole Sculptures and Wall Works, Albertine Monroe- Brown Gallery, Western Michigan University, Kalamazoo, MI (traveling); Weatherspoon Art Museum, University