Nuclear Pakistan Seeking Security & Stability

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NEWSLETTER a Quarterly Publication of National Centre for Non-Destructive Testing

NEWSLETTER A quarterly publication of National Centre for Non-destructive Testing, Scientific and Engineering Services Dte., Pakistan Atomic Energy Commission Issue No 29 July-September,2002 Back to Main Contents Editorial Tube Plugging Criteria for Heat Exchangers, Boilers and Condensers, etc. Application of Mechanized Ultrasonic Testing in lieu of Radiographic Testing during the Construction of Pipeline for Petroleum Products Seminars on NDT o Experience of WAPDA using NDT as a Tool for Turbine Maintenance o The Role of NDT Technology in the Industrial Development of Pakistan Investiture of PASNT o PASNT Website o Training Courses Conducted o Training Courses Planned for 2003 o Happy News o Global Harmonization of NDT Certification under ISO- 9712 o Industrial NDT Services o In-service Inspection of CHASNUPP Conventional Island (CI) by NCNDT o International NDT News o Foreign Assignment o Visitors Gallery o Visit of NCNDT & CHASNUPP Officers o Private Advertisement EDITORIAL Last issue of this Newsletter was brought out in a new getup. Snaps of members of the Editorial Board were added. Table of contents was included (Previously we faced difficulty in referring to a news item that appeared in a certain issue and had to browse through the pages of many issues in order to locate a desired news). Similarly, titles like International NDT News, Visitors gallery and account of Visits of National Centre for Non-destructive Testing (NCNDT) Personnel were included. This gave new dimensions to the scope of our Newsletter. All this was possible by the contribution of ideas given by the members of newly constituted Editorial Board. It is felt that the readers would have appreciated it. -

CISS Insight

©Copyright, Center for International Strategic Studies (CISS) All rights are reserved. No part of the contents of this publication may be reproduced, adapted, transmitted, or stored in any form by any process without the written permission of the Center for International Strategic Studies, Islamabad. ADVISORY BOARD Dr. Naeem Ahmed Salik, Senior Research Fellow CISS Dr. Adil Sultan, Ph.D Qauid-e-Azam University Dr. Tahir Amin, VC, Bahauddin Zakariya University Dr. Shabana Fayyaz, Assistant Professor, Qauid-e-Azam University Dr. Zafar Iqbal Cheema, President Strategic Vision Institute, Islamabad Dr. Salma Shaheen, Independent Analyst, United Kingdom Dr. Christine M. Leah, Ph.D, Australian National University Dr. Walter Anderson, Senior Adjunct Professor, John Hopkins University Dr. Rizwan Zeb, Independent Analyst, Australia EDITORIAL BOARD Editor in Chief Ambassador (Rtd) Ali Sarwar Naqvi Editor Col. (Rtd) Iftikhar Uddin Hasan Associate Editor Ms. Saima Aman Sial Assistant Editor Ms. Maryam Zubair IT Support Shahid Wasim Malik www.ciss.org.pk @CISSOrg1 Center for International Strategic Studies (CISS) May 2018 SPECIAL ISSUE CISS Insight Two Decades after the Nuclear Test in South Asia Center for International Strategic Studies Islamabad CONTENTS PAGE Foreword 01 ARTICLES: i Strategic Environment Pre-May 1998 04 Maryam Zubair Exploring Pakistan’s Decision-making Process for ii the Nuclear Tests: Those Seventeen Days 15 Muhammad Sarmad Zia and Saima Aman Sial India And Pakistan’s Nuclear Tests And iii International Reactions 38 Huma Rehman and Afeera Firdous iv Pakistan’s Nuclear Tests: Assured No Fallouts 62 Dr. Syed Javaid Khurshid 4 CISS Insight: Special Issue Foreword May 1998 was a fateful month in the history of South Asia. -

THE UNIVERSITY RESEARCH SYSTEM in PAKISTAN the Pressure to Publish and Its Impact 26 Summary 27 03 RESEARCH and RELATED FUNDING 29

knowledge platform KNOWLEDGE PLATFORM THE UNIVERSITY DR. NADEEM UL HAQUE MAHBOOB MAHMOOD SHAHBANO ABBAS RESEARCH SYSTEM ALI LODHI IN PAKISTAN BRITISH COUNCIL DR. MARYAM RAB CATHERINE SINCLAIR JONES THE UNIVERSITY A KNOWLEDGE PLATFORM PROJECT IN COLLABORATION WITH RESEARCH SYSTEM THE BRITISH COUNCIL IN PAKISTAN IN PAKISTAN DR. NADEEM UL HAQUE MAHBOOB MAHMOOD SHAHBANO ABBAS ALI LODHI DR.MARYAM RAB CATHERINE SINCLAIR JONES Contents FOREWORD 1 INTRODUCTION 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 5 01 THE UNIVERSITY SYSTEM IN PAKISTAN 11 02 LITERATURE REVIEW 21 Overview 22 HEC influence 23 The imperative to collaborate 24 The weakness of social sciences research 25 THE UNIVERSITY RESEARCH SYSTEM IN PAKISTAN The pressure to publish and its impact 26 Summary 27 03 RESEARCH AND RELATED FUNDING 29 Overview 30 Government-linked research institutes 33 Pakistan science foundation 40 Industry cess-based funds 41 Donor funding 44 Other funding 47 Pathways to enhanced funding 48 04 DRIVERS OF RESEARCH DEMAND 53 Overview 54 Government demand 55 Business demand 60 Donor demand 65 Pathways to building demand 70 05 RESEARCH INCENTIVES AND MEASUREMENT 73 Overview 74 Community perspectives 77 Pathways to quality-oriented incentives and measurements 80 06 v RESEARCH CULTURE AND ITS DISCONTENTS 83 Overview 84 Research collaboration 92 07 Research practice 95 FACULTY AND INSTITUTIONAL CAPABILITIES 103 Overview 104 Faculty capabilities 108 Gender impact 113 Institutional capabilities 115 08 Pathways to building faculty and institutional capabilities 117 09 COMPARATIVE RESEARCH SYSTEMS -

Mining Industry Impact on Environmental Sustainability

processes Article Mining Industry Impact on Environmental Sustainability, Economic Growth, Social Interaction, and Public Health: An Application of Semi-Quantitative Mathematical Approach Muhammad Mohsin 1 , Qiang Zhu 1, Sobia Naseem 2,*, Muddassar Sarfraz 3,4,* and Larisa Ivascu 4,5 1 School of Business, Hunan University of Humanities, Science and Technology, Loudi 417000, China; [email protected] (M.M.); [email protected] (Q.Z.) 2 School of Economics and Management, Shijiazhuang Tiedao University, Shijiazhuang 050043, China 3 College of International Students, Wuxi University, Wuxi 214105, China 4 Research Center for Engineering and Management, Politehnica University of Timisoara, 300191 Timisoara, Romania; [email protected] 5 Faculty of Management in Production and Transportation, Politehnica University of Timisoara, 300191 Timisoara, Romania * Correspondence: [email protected] (S.N.); [email protected] (M.S.); Tel.: +86-18751861057 (M.S.) Abstract: The mining industry plays a significant role in economic growth and development. Coal is a viable renewable energy source with 185.175 billion deposits in Thar, which has not been deeply explored. Although coal is an energy source and contributes to economic development, it puts pressure on environmental sustainability. The current study investigates Sindh Engro coal mining’s impact on environmental sustainability and human needs and interest. The Folchi and Citation: Mohsin, M.; Zhu, Q.; Phillips Environmental Sustainability Mathematics models are employed to measure environmental Naseem, S.; Sarfraz, M.; Ivascu, L. sustainability. The research findings demonstrated that Sindh Engro coal mining is potentially Mining Industry Impact on unsustainable for the environment. The toxic gases (methane, carbon dioxide, sulfur, etc.) are released Environmental Sustainability, during operational activities. -

Governing the Ungovernable? Reflections on Informal Gemstone Mining in High-Altitude Borderlands of Gilgit-Baltistan, Pakistan

Local Environment The International Journal of Justice and Sustainability ISSN: 1354-9839 (Print) 1469-6711 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/cloe20 Governing the ungovernable? Reflections on informal gemstone mining in high-altitude borderlands of Gilgit-Baltistan, Pakistan Kuntala Lahiri-Dutt & Hugh Brown To cite this article: Kuntala Lahiri-Dutt & Hugh Brown (2017) Governing the ungovernable? Reflections on informal gemstone mining in high-altitude borderlands of Gilgit-Baltistan, Pakistan, Local Environment, 22:11, 1428-1443, DOI: 10.1080/13549839.2017.1357688 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/13549839.2017.1357688 Published online: 30 Aug 2017. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 248 View related articles View Crossmark data Citing articles: 1 View citing articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=cloe20 LOCAL ENVIRONMENT, 2017 VOL. 22, NO. 11, 1428–1443 https://doi.org/10.1080/13549839.2017.1357688 Governing the ungovernable? Reflections on informal gemstone mining in high-altitude borderlands of Gilgit-Baltistan, Pakistan Kuntala Lahiri-Dutt a and Hugh Brownb aResource Environment & Development Program, Crawford School of Public Policy ANU College of Asia and the Pacific, The Australian National University, Canberra, Australian Capital Territory, Australia; bIndependent Researcher and Photographer, Darlington, Western Australia, Australia ABSTRACT ARTICLE HISTORY The ethnically diverse high-altitude region of Gilgit-Baltistan, with its Received 8 November 2016 complex political history, remains relatively free from the controlling Accepted 30 June 2017 gaze of the central state apparatus of Pakistan. In these extraordinary KEYWORDS terrain, where local communities rule the region as the “State by proxy”, Informal mining; informal gemstone mining provides an important supplement to ungovernability; ASM; livelihoods. -

A If1 S /M Laici Strp\ I States That Are Parties to the Convention

I 'I : •' • - ,1. i- a. 5 "r APRIL/MAY 1999, VOLUME 14, NUMBER 2 (83) INIS-XA-165 XA9950270 M Sfa iT w n ( & A i [3 t & ft JS^ M K vr ft Si "Si #*^ A if1 s /M lAICi STrP\ i States that are parties to the Convention. Sessions included lations - it was nevertheless not- international Convention on the presentation of national ed that all Contracting Parties par- Nuclear Safety are taking "steps reports from Contracting Parties ticipating in the meeting are in the right direction"to achieve on their nuclear safety pro- taking steps in the right direction. and maintain a high level of safe- grammes, specifically focusing on The full Summary Report of ty at nuclear installations. The measures they have taken and the meeting was issued 23 April Convention's Contracting Parties planned to implement the 1999 and is accessible over the met for two weeks in April at Convention in their respective IAEA's WoridAtom Internet ser- IAEA headquarters in Vienna to countries. Each national report vices at http://www.iaea.org. The review progress and plans. The was reviewed and discussed in site additionally includes links to two-week Review Meeting - depth, including the exchange of the full text of the Convention with participation by 45 of the written questions and comments. and the latest status list of Convention's 50 Parties — was In a concluding Summary Contracting Parties. Also acces- the first within the framework of Report, the Contracting Parties sible on the site's NuSafe Web the Convention, which came into noted that the review process pages (www.iaea.org/ns/nusafe) force in 1996 and calls for such had demonstrated the strong are national reports and back- "peer review" meetings to be commitment to the Convention's ground information about the convened at three-year intervals. -

Mining in Pakistan a Private Sector Point of View

MINING IN PAKISTAN A PRIVATE SECTOR POINT OF VIEW BY ENGR. MUHAMMAD KHALID PERVAIZ, PRESIDENT, IMEP/ CHIEF EXECUTIVE ENERPOOL/ DIRECTOR PER/GEOMINERAL ASSOCIATES AND A PRIVATE CONSULTANT FOR WORLD BANK SPONSORED CONSULTATIVE WORKSHOP JOINTLY ORGANIZED BY MINISTRY OF PETROLEUM & NATURAL RESOURCES AT OGDCL CONFERENCE ROOM, ISLAMABAD ON 15TH AND 16TH DECEMBER 03 OGDC 15-16 DEC:03 ISLAMABAD BEWARE ! ARE THERE WE ARE MINERALS? SERIOUS REASSURE IN HUNTING YOUR THE SOLID POTENTIALS MINERALS AND THEN GOP WORLD EVEN IF BANK REST HOUSED IN ASSURED OGDC ARENA FOR ASSISTANCE MPNR NWFP BALOCHISTAN SINDH PUNJAB WHERE WE STAND IN OUR ROLE & SHARE WARM WELCOME TO WORLD BANK DELEGATES FROM LOCALS PARTICIPANTS STAKEHOLDERS DEVELOPING CONSENSUS OVER WORLD BANK POLICY NOTE •Globally Rich Volume of Knowledge embodied in the report. • A realistic assessment on Pakistan Mineral Status. • A road map for recovery to prosperity. • Role model of Argentina, Malaysia & some African countries an ample guidelines for take off. •The Architect of the report have done a commendable job & deserve appreciations. •Comments asked for will follow at the end of presentation on private sector point of view. HATS OFF ? • IMEP & PMS extend deep felicitation to MOP-NR and World Bank for organizing the workshop. • Pakistan has not driven eminence in the global mineral market despite potential of 57 exploitable minerals • Who is responsible: - • Minerals, Men, Marketer or Ministry? Please take the hats off and wake up for joint efforts. • The hostile Geo-Political Environments around Pakistan & global media campaign has unnecessarily apprehended the friendly investors. No more worry. • Time is paving the way for developing potentials of investment opportunities in Pakistan Mineral Sector (PMS). -

Resume of Dr. Syed Javaid Khurshid's CV

Resume & CV - Dr. Syed Javaid Khurshid March 23, 2018 Resume of Dr. Syed Javaid Khurshid’s CV Dr. Syed Javaid Khurshid is B.Sc. (Hons) Organic Chemistry, 1972, MSc. Radiation Chemistry, 1973, Karachi University, MS Organic/Biochemistry Ball State University, Indiana, USA and Ph.D. from University of the Punjab in Biochemistry & Radiation Chemistry, 1993. Dr. Javaid worked for Pakistan Atomic Energy Commission (PAEC) for 40 years in different capacities as Consultant/Advisor/Director General/Director of Planning, Development & Projects Coordination, Biosciences & Executive Secretary, Abdu’s Salam International Nathiagali Summer College. Present Work: Dr. Javaid is, President Pakistan Nuclear Society, comprising of 3000 Nuclear Scientists, Engineers & Professionals. He is Distinguished Visiting Fellow at Centre for International Strategic Studies. His special interest is Mitigation and development of Confidence Building Measures on WMD & CBRNe, Code of conducts & Ethics, Nuclear Knowledge Management, Nuclear Energy & Climate Change and Nuclear Technology for achieving SDGs, Science Communication and Science Diplomacy. He delivers lectures/hold seminars at different forums & Pakistani Universities. He is Director at Large of Planning Management Institute, PA, USA (Isld Chapt). He is Secretary National Member Organization, IIASA Laxenburg, Austria. Adjunct Faculty Member of Department of Communication & Management Sciences, PIEAS, deliver lectures on Leadership and Project Preparation, Implementation, Monitoring & Evaluation. He is Technical Committee Member of Higher Education Commission-Ministry of Foreign Affairs-Internal Compliance Committee on Export Control Laws. Dr. Javaid was on three committees of Health, Nutrition and Energy of 5-year Plan 2013-18. Associate Editor Journal of Pioneering Medical Sciences, USA. He is Member Advisory Council of “Global Affairs”, a magazine circulated in 19 countries. -

Revised Stratigraphy and Mineral Resources of Balochistan Basin, Pakistan: an Update

Open Journal of Geology, 2020, 10, 784-828 https://www.scirp.org/journal/ojg ISSN Online: 2161-7589 ISSN Print: 2161-7570 Revised Stratigraphy and Mineral Resources of Balochistan Basin, Pakistan: An Update Muhammad Sadiq Malkani Geological Survey of Pakistan, Muzaffarabad, Azad Kashmir, Pakistan How to cite this paper: Malkani, M.S. Abstract (2020) Revised Stratigraphy and Mineral Resources of Balochistan Basin, Pakistan: The Balochistan basin is located on the south western part of Balochistan An Update. Open Journal of Geology, 10, Province and also Pakistan. Balochistan super basin is subdivided into north- 784-828. ern Balochistan (Pishin basin or Kakar Kohorasan basin represented as back https://doi.org/10.4236/ojg.2020.107036 arc basin), central Balochistan (Chagai-Raskoh-Wazhdad Magmatic arc and Received: May 3, 2020 Hamuns-Inter arc basin) and southern Balochistan (Makran Siahan basin) Accepted: July 27, 2020 basins. Balochistan basin consists of Cretaceous to recent sediments, diverse Published: July 30, 2020 igneous rocks and low grade metamorphics. Balochistan basin is a leading Copyright © 2020 by author(s) and basin which consists of very significant mineral deposits especially copper Scientific Research Publishing Inc. and gold deposits. These mineral resources need to be developed for the de- This work is licensed under the Creative velopment of areas, province and Pakistan. During previous half century a lot Commons Attribution International of geological work has been done in Balochistan basin. Here the revised stra- License (CC BY 4.0). http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ tigraphic set up and its mineral resources with an update are being presented. -

Pakistan Coal Power Generation Potential

PAKISTAN Coal Power Generation Potential Coal Power Generation Chain Mine: Refuse disposal: Cleaning plant: Transportation: Boiler: Storage: Pulverizer: Baghouse: FGD System: Ash and sludge disposal: PRIVATE POWER & INFRASTRUCTURE BOARD ......................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... -

Year Book 2017-2018

YEAR BOOK 2017-2018 GOVERNMENT OF PAKISTAN MINISTRY OF ENERGY (PETROLEUM DIVISION) A-BLOCK PAK-SECRETARIAT ISLAMABAD TABLE OF CONTENTS S # Description Page No. 1. GENERAL…………………………………………………………… 1-7 MISSION STATEMENT……………………………………………. 2 STRATEGY TO ACHIEVE MISSION……………………………….. 2 FUNCTIONS OF THE DIVISION………………………………… 2 ORGANIZATION OF THE DIVISION……………………………. 3 ADMINISTRATION WING…………………………………………. 5 DEVELOPMENT WING (INVESTMENT & JOINT VENTURE)… 5 MINERAL WING…………………………………………………….. 5 POLICY WING………………………………………………………. 6 ATTACHED DEPARTMENT, AUTONOMOUS BODIES, 6 CORPORATIONS AND COMPANIES OF THE DIVISION WEBSITE OF THE DIVISION…………………………………….. 7 2. ACTIVITIES, ACHIEVEMENTS AND PROGRESS 8-17 MINERAL WING…………………………………………………… 9 POLICY WING…………………………………………………….. 11 (i) DIRECTORATE GENERAL OF OIL………………... 11 (ii) DIRECTORATE GENERAL OF GAS ………………. 13 (iii) DIRECTORATE GENERAL OF LIQUEFIED 16 GASES………………... (iv) DIRECTORATE GENERAL OF PETROLEUM 16 CONCESSIONS…………………. 3. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY OF PAKISTAN (GSP)……………….. 18-33 INSTITUTIONAL STRUCTURE…..……………………………...... 19 BUDGET AND FINANCE …………………………………………. 20 ACTIVITIES, ACCOMPLISHMENTS AND PROGRESS ………. 21 RESEARCH STUDIES…………… 21 i 4. HYDROCARBON DEVELOPMENT INSTITUTE OF PAKISTAN 34-39 (HDIP)…………...................................................... INTRODUCTION…………………………………………………… 35 UPSTREAM ACTIVITIES………………………………………….. 36 DOWNSTREAM ACTIVITIES…………………………………….. 38 COMPANIES……………………………………………………… 5. OIL AND GAS DEVELOPMENT COMPANY LIMITED ………… 40 6. PAKISTAN PETROLEUM LIMITED……………………… 44 7. GOVERNMENT -

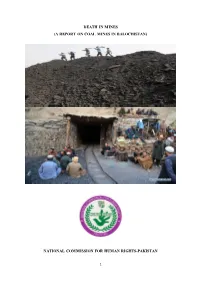

View Report on Coal Mines in Balochistan

DEATH IN MINES (A REPORT ON COAL MINES IN BALOCHISTAN) NATIONAL COMMISSION FOR HUMAN RIGHTS-PAKISTAN 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION.................................................................................................................... 6 SITUATION OF COAL MINES IN BALOCHISTAN ........................................................ 9 BALOCHISTAN MINES ACT 1923. .................................................................................. 13 RECOMMENDATIONS....................................................................................................... 16 2 3 4 5 THE MESSAGE OF THE CHAIRMAN National Commission for Human Rights- NCHR is committed to protect the basic human rights of labours in coal mines in Pakistan, particularly in Balochistan, Because the coal mines are the only industry in Balochistan province, It needs more attention and protection to improve the economic lives of people of Balochistan who are engaged in this sector. It is believed that mining companies are violating human where labours work for underground coal and coal mines are particularly prone to safety lapses and poor working conditions. During hearings before the Functional Committee on Human Rights Senate it was learnt that the main power of regularity bodies is totally inadequate. There are sub leases and the actual persons operating in mine areas are not lease holder of the provincial government. These persons exploit the labours, dodge taxation and do not take care of the safety of poor mining workers in Balochsitan. The Government