Information to Users

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download File

The Outward Turn: Personality, Blankness, and Allure in American Modernism Anne Claire Diebel Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2013 © 2013 Anne Claire Diebel All rights reserved ABSTRACT The Outward Turn: Personality, Blankness, and Allure in American Modernism Anne Claire Diebel The history of personality in American literature has surprisingly little to do with the differentiating individuality we now tend to associate with the term. Scholars of nineteenth- and twentieth-century American culture have defined personality either as the morally vacuous successor to the Protestant ideal of character or as the equivalent of mass-media celebrity. In both accounts, personality is deliberately constructed and displayed. However, hiding in American writings of the long modernist period (1880s–1940s) is a conception of personality as the innate capacity, possessed by few, to attract attention and elicit projection. Skeptical of the great American myth of self-making, such writers as Henry James, Theodore Dreiser, Gertrude Stein, Nathanael West, and Langston Hughes invented ways of representing individuals not by stable inner qualities but by their fascinating—and, often, gendered and racialized—blankness. For these writers, this sense of personality was not only an important theme and formal principle of their fiction and non-fiction writing; it was also a professional concern made especially salient by the rise of authorial celebrity. This dissertation both offers an alternative history of personality in American literature and culture and challenges the common critical assumption that modernist writers took the interior life to be their primary site of exploration and representation. -

Varieties of Religious Experience

Varieties of Religious Experience Author(s): James, William Publisher: Grand Rapids, MI: Christian Classics Ethereal Library Description: This collection of 20 lectures was presented by William James at the 1901-1902 Gifford Lectures in Edinburgh. In these lectures, James explores individual religious experience as it varies among humans. James associates religious experi- ence with the feelings and actions of individuals in a relation- ship with what they believe to be the Divine. James digs deep into the psychological underpinnings of religious experience; he is less concerned with studying religious institutions and theology. He discusses the origin, nature, and variation of religious experience and raises questions about its power. Some of his lectures focus on conversion, others on mysti- cism or virtue. His empirical study of human nature and indi- vidual religious experiences is remarkable complex, and yet his style of presentation is accessible to a wide variety of audiences. James© lectures come together to form the brilliant intertwining of religion, philosophy, and psychology. Emmalon Davis CCEL Staff Writer i Contents Title Page 1 Preface. 2 Lecture I. Religion and Neurology. 3 Lecture II. Circumscription of the Topic. 18 Lecture III. The Reality of the Unseen. 34 Lectures IV and V. The Religion of Healthy-Mindedness. 50 Lectures IV and V. 80 Lectures VI and VII. The Sick Soul. 83 Lecture VIII. The Divided Self, and the Process of Its Unification. 107 Lecture IX. Conversion 122 Lecture X. Conversion—Concluded 140 Lectures XI, XII, and XIII. Saintliness. 167 Lectures XIV and XV. The Value of Saintliness. 210 Lectures XVI and XVII. -

Kindred Ambivalence

KINDRED AMBIVALENCE: ART AND THE ADULT-CHILD DYNAMIC IN AMERICA’S COLD WAR by MICHAEL MARBERRY A THESIS Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of English in the Graduate School of The University of Alabama TUSCALOOSA, ALABAMA 2010 Copyright Michael Marberry 2010 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT The pervasive ideological dimension of the Cold War resulted in an extremely ambivalent period in U.S. history, marked by complex and conflicting feelings. Nowhere is this ambivalence more clearly seen than in the American home and in the relationship between adults and children. Though the adult-child dynamic has frequently harbored ambivalent feelings, the American Cold War era—with its increased emphasis on the family in the face of ideological struggle—served to highlight this ambivalence. Believing that art reveals historical and cultural concerns, this project explores the extent to which adult-child ambivalence is prominent within American art from the period—particularly, the coming-of-age story, as it is a genre intrinsically concerned with the interactions between adults and children. Chapter one features an analysis of Katherine Anne Porter’s “Old Order” coming-of-age sequence, specifically “The Source” and “The Circus.” Establishing Porter’s relevance to the Cold War period, this chapter illustrates how her young heroine (Miranda Gay) experiences ambivalence within her familial relationships—which, in turn, comes to foreshadow and represent the adult-child ambivalence within the Cold War period. Chapter two expands its scope to include a larger historical context and a different artistic mode. With the rise of cinema during the Cold War period, the horror film became a genre extremely interested in adult-child ambivalence, frequently depicting the child as a destructive force and the adult as a victim of parenthood. -

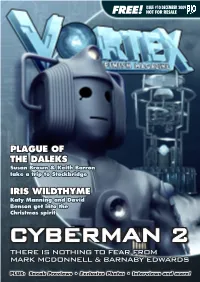

Plague of the Daleks Iris Wildthyme

ISSUE #10 DECEMBER 2009 FREE! NOT FOR RESALE PLAGUE OF THE DALEKS Susan Brown & Keith Barron take a trip to Stockbridge IRIS WILDTHYME Katy Manning and David Benson get into the Christmas spirit CYBERMAN 2 THERE IS NOTHING TO FEAR FROM MARK MCDONNELL & barnaby EDWARDS PLUS: Sneak Previews • Exclusive Photos • Interviews and more! EDITORIAL THE BIG FINISH SALE Hello! This month’s editorial comes to you direct Now, this month, we have Sherlock Holmes: The from Chicago. I know it’s impossible to tell if that’s Death and Life, which has a really surreal quality true, but it is, honest! I’ve just got into my hotel to it. Conan Doyle actually comes to blows with Prices slashed from 1st December 2009 until 9th January 2010 room and before I’m dragged off to meet and his characters. Brilliant stuff by Holmes expert greet lovely fans at the Doctor Who convention and author David Stuart Davies. going on here (Chicago TARDIS, of course), I And as for Rob’s book... well, you may notice on thought I’d better write this. One of the main the back cover that we’ll be launching it to the public reasons we’re here is to promote our Sherlock at an open event on December 19th, at the Corner Holmes range and Rob Shearman’s book Love Store in London, near Covent Garden. The book will Songs for the Shy and Cynical. Have you bought be on sale and Rob will be signing and giving a either of those yet? Come on, there’s no excuse! couple of readings too. -

Literary Skirmish Over Hiss

T SDA:Y;J Above photos he Assoateted Pre se: ROght photo from the dust Jacket or "Perim's,: The Hiss-Chambers Case" Then-Rep. Richard Nixon, above left. Whittaker Chambers and Alger Hiss, right. Far right, Allen Weinstein. Entertainment / People / The Arts APRIL 6, 1978 B1 A Literary Skirmish Over Hiss Attack and Counterattack, in a Battle Fought for 30 Years And so, Alistair Cooke's comment By Michael Kernan that the case put "a generation on trial" continues to reverberate. The Hiss-Chambers affair is 30 Years old and heading into its second Weinstein's book, five years in the generation — and people who were in writing, draws on a huge mass of new knee pants when it began still get material — 30,000 pages of FBI and fighting mad over It. Justice Department records, Inter- views with former Soviet spymasters The latest episode on Publishers and other figures — so overwhelming, Row is the lead article in the April 8 Weinstein says, that he himself Nation magazine, titled "The Case switched from his initial belief in Not Proved Against Alger Hiss, an In- Hiss' innocence. vestigation by Victor Navasky." It consists of an attack on Allen Wein- And now Navasky attacks the 40- stein's just-published book, which con- year-old Smith College historian with cludes that Hiss was "guilty as a series of statements by Weinstein charged" of perjury. interviewees denying some of the things that the book has them saying. And Weinsteln's book, "Perjury: The Hiss-Chambers Case," followed I sent Xeroxed galleys to the on the heels of another book, by John sources for some of Weinsteins most Chabot Smith. -

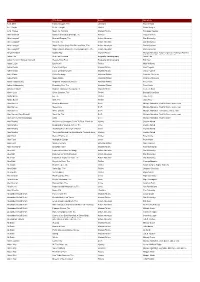

List of All the Audiobooks That Are Multiuse (Pdf 608Kb)

Authors Title Name Genre Narrators A. D. Miller Faithful Couple, The Literature Patrick Tolan A. L. Gaylin If I Die Tonight Thriller Sarah Borges A. M. Homes Music for Torching Modern Fiction Penelope Rawlins Abbi Waxman Garden of Small Beginnings, The Humour Imogen Comrie Abie Longstaff Emerald Dragon, The Action Adventure Dan Bottomley Abie Longstaff Firebird, The Action Adventure Dan Bottomley Abie Longstaff Magic Potions Shop: The Blizzard Bear, The Action Adventure Daniel Coonan Abie Longstaff Magic Potions Shop: The Young Apprentice, The Action Adventure Daniel Coonan Abigail Tarttelin Golden Boy Modern Fiction Multiple Narrators, Toby Longworth, Penelope Rawlins, Antonia Beamish, Oliver J. Hembrough Adam Hills Best Foot Forward Biography Autobiography Adam Hills Adam Horovitz, Michael Diamond Beastie Boys Book Biography Autobiography Full Cast Adam LeBor District VIII Thriller Malk Williams Adèle Geras Cover Your Eyes Modern Fiction Alex Tregear Adèle Geras Love, Or Nearest Offer Modern Fiction Jenny Funnell Adele Parks If You Go Away Historical Fiction Charlotte Strevens Adele Parks Spare Brides Historical Fiction Charlotte Strevens Adrian Goldsworthy Brigantia: Vindolanda, Book 3 Historical Fiction Peter Noble Adrian Goldsworthy Encircling Sea, The Historical Fiction Peter Noble Adriana Trigiani Supreme Macaroni Company, The Modern Fiction Laurel Lefkow Aileen Izett Silent Stranger, The Thriller Bethan Dixon-Bate Alafair Burke Ex, The Thriller Jane Perry Alafair Burke Wife, The Thriller Jane Perry Alan Barnes Death in Blackpool Sci Fi Multiple Narrators, Paul McGann, and a. cast Alan Barnes Nevermore Sci Fi Multiple Narrators, Paul McGann, and a. cast Alan Barnes White Ghosts Sci Fi Multiple Narrators, Tom Baker, and a. cast Alan Barnes, Gary Russell Next Life, The Sci Fi Multiple Narrators, Paul McGann, and a. -

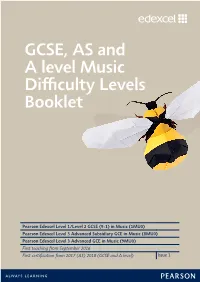

GCSE, AS and a Level Music Difficulty Levels Booklet

GCSE, AS and A level Music Difficulty Levels Booklet Pearson Edexcel Level 1/Level 2 GCSE (9 - 1) in Music (1MU0) Pearson Edexcel Level 3 Advanced Subsidiary GCE in Music (8MU0) Pearson Edexcel Level 3 Advanced GCE in Music (9MU0) First teaching from September 2016 First certification from 2017 (AS) 2018 (GCSE and A level) Issue 1 Contents Introduction 1 Difficulty Levels 3 Piano 3 Violin 48 Cello 71 Flute 90 Oboe 125 Cla rinet 146 Saxophone 179 Trumpet 217 Voic e 240 Voic e (popula r) 301 Guitar (c lassic al) 313 Guitar (popula r) 330 Elec tronic keyboa rd 338 Drum kit 344 Bass Guitar 354 Percussion 358 Introduction This guide relates to the Pearson Edexcel Level 1/Level 2 GCSE (9-1) in Music (1MU0), Pearson Edexcel Level 3 Advanced Subsidiary GCE in Music (8MU0) and Pearson Edexcel Level 3 Advanced GCE in Music (9MU0) qualifications for first teaching from 2016. This guide must be read and used in conjunction with the relevant specifications. The music listed in this guide is designed to help students, teachers, moderators and examiners accurately judge the difficulty level of music submitted for the Performing components of the Pearson Edexcel GCSE, AS and A level Music qualifications. Examples of solo pieces are provided for the most commonly presented instruments across the full range of levels. Using these difficult y levels For GCSE, teachers will need to use the book to determine the difficulty level(s) of piece(s) performed and apply these when marking performances. For AS and A Level, this book can be used as a guide to assist in choosing pieces to perform, as performances are externally marked. -

Carey Mcwilliams Papers, 1894-1982 (Bulk 1921-1980)

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf1779n6sf No online items Finding Aid for the Carey McWilliams Papers, 1894-1982 (bulk 1921-1980) Processed by Andrea Eitsert, with assistance from Laurel McPhee; machine-readable finding aid created by Caroline Cubé UCLA Library, Department of Special Collections Manuscripts Division Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.library.ucla.edu/libraries/special/scweb/ © 1999 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Finding Aid for the Carey 1319 1 McWilliams Papers, 1894-1982 (bulk 1921-1980) Finding Aid for the Carey McWilliams Papers, 1894-1982 (bulk 1921-1980) Collection number: 1319 UCLA Library, Department of Special Collections Manuscripts Division Los Angeles, CA Contact Information Manuscripts Division UCLA Library, Department of Special Collections Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 Telephone: 310/825-4988 (10:00 a.m. - 4:45 p.m., Pacific Time) Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.library.ucla.edu/libraries/special/scweb/ Processed by: Andrea Eitsert, with assistance from Laurel McPhee, Winter 2006 Encoded by: Caroline Cubé Online finding aid edited by: Josh Fiala, March 2002 and Caroline Cubé, June 2006 © 1999 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Title: Carey McWilliams Papers, Date (inclusive): 1894-1982 (bulk 1921-1980) Collection number: 1319 Creator: McWilliams, Carey, 1905- Extent: 80 boxes (40 linear ft.)11 oversize boxes repository: University of California, Los Angeles. Library. Department of Special Collections. -

WSFA Journal 69

. »x.'N ■ •*' p. l^-> = f/M'i/ilf'if'''-. ///" fiii: It I - . ■I»'• n, ll i.^/f f •] ! i W 'i j :i m y't ) ' ' / •* ' - t *> '.■; ■ *"<* '^ii>fi<lft'' f - ■ ■//> ■ vi '' • ll. F V -: ■ :- ^ ■ •- ■tiK;- - :f ii THE WSFA journal (The Official Organ of the Washington Science Fiction Association) Issue Number 69: October/November, 1969 The JOURNAL Staff — Editor & Publisher: Don Miller, 12315 Judson Rd., Wheaton, Maryland, .•U.S.A., 20906. ! Associate Editors: Alexis & Doll Gilliland, 2126 Pennsylvania Ave,, N.W., Washington, D.C., U.S.A., 20037. Cpntrib-uting Editors:- ,1 . " Art Editor — Alexis Gilliland. - 4- , . Bibliographer— Mark Owings. Book Reviewers — Alexis Gilliland,• David Haltierman, Ted Pauls. Convention Reporter — J.K. Klein. ' : . r: Fanzine Reviewer — Doll Golliland "T Flltfl-Reviewer — Richard Delap. ' " 5 P^orzine Reviewer — Banks.Mebane. Pulps — Bob Jones. Other Media Ivor Rogers. ^ Consultants: Archaeology— Phyllis Berg. ' Medicine — Bob Rozman. Astronomy — Joe Haldeman. Mythology — Thomas Burnett Biology — Jay Haldeman. Swann, David Halterman. Chemistry — Alexis Gilliland. Physics — Bob Vardeman. Computer Science — Nick Sizemore. Psychology -- Kim West on. Electronics — Beresford .Smith. Mathematics — Ron Bounds, Steve Lewis. Translators: . French .— Steve Lewis, Gay Haldeman. Russian — Nick Sizemore, German -- Nick Sizemore. Danish ~ Gay. Haldeman, Italian ~ OPEN. Joe Oliver. Japanese. — OPEN. Swedish" -- OBBN. Overseas Agents: Australia — Michael O'Brien, 158 Liverpool St., Holaart, Tasmania, Australia, 7000. • South Africa — A.B. Ackerman, P^O.Box 6, Daggafontein, .Transvaal, South Africa, . ^ United Kingdom — Peter Singleton, 60ljU, Blodc h, Broadiiioor Hospital, Crowthome, Berks, RGll 7EG, United Kingdom. Needed for France, Germany, Italy, Scandinavia, Spain, S.America, NOTE; Where address are not listed above, send material ^Editor, Published bi-monthly. -

John Herrmann

John Herrmann: An Inventory of His Collection at the Harry Ransom Center Descriptive Summary Creator: Herrmann, John, 1900-1959 Title: John Herrmann Collection Dates: 1923-1971, undated Extent: 3 boxes (1.26 linear feet), 1 galley folder (gf) Abstract: Includes manuscripts and letters written by the expatriate novelist John Herrmann, as well as letters he received, and items associated with his first wife, the writer Josephine Herbst, including a photo album with her reminiscences. Correspondents include Sylvia Beach, John Dos Passos, Ford Madox Ford, Ernest Hemingway, Herbst, H. L. Mencken, Katherine Anne Porter, William Carlos Williams, and others. Call Number: Manuscript Collection MS-1928 Language: English, French, and German Access: Open for research Administrative Information Processed by: Joan Sibley and Jamie Hawkins-Kirkham, 2011 Note: This finding aid replicates and replaces information previously available only in a card catalog. Please see the explanatory note at the end of this finding aid for information regarding the arrangement of the manuscripts as well as the abbreviations commonly used in descriptions. Repository: The University of Texas at Austin, Harry Ransom Center Herrmann, John, 1900-1959 Manuscript Collection MS-1928 2 Herrmann, John, 1900-1959 Manuscript Collection MS-1928 Works: Unidentified collection of works, galley proofs/ incomplete, 9 pages, undated. Container Contents: primarily Foreign born and I hear you, Mr. and Mrs. Smith. gf 1 Unidentified essay on writing and what books sell, typescript with one handwritten Container correction, 3 pages, undated. 1.1 Unidentified novel, typed and carbon manuscript/ incomplete with handwritten revisions and corrections, 69 pages, undated. Includes drafts of the first two chapters of a proposed 24-chapter book. -

Scopeofsovietact2730unit.Pdf

POSITORT SCOPE OF SOVIET ACTIVITY IN THE UNITED STATES HEARINGS BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE TO INVESTIGATE THE ADMINISTRATION OF THE INTERNAL SECURITY ACT AND OTHER INTERNAL SECURITY LAWS OF THE COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY UNITED STATES SENATE EIGHTY-FOURTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION ON SCOPE OF SOVIET ACTIVITY IN THE UNITED STATES JUNE 12 AND 14, 1956 PART 27 (With Sketch of the Career of J. Peters) Printed for the use of the Committee on the Judiciary UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 72723 WASHINGTON : 1956 vsoTieo Boston Public Library Superintendent of Document* JAN 2 8 1957- COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY JAMES 0. EASTLAND, Mississippi, Chairman ESTDS KEFAUVER, Tennessee ALEXANDER WILEY, Wisconsin OLIN D. JOHNSTON, South Carolina WILLIAM LANGER, North Dakota THOMAS C. HENNINGS, Jr., Missouri WILLIAM E. JENNER, Indiana JOHN L. McCLELLAN, Arkansas ARTHUR V. WATKINS, Utah PRICE DANIEL, Texas EVERETT McKINLEY DIRKSEN, Illinois JOSEPH C. O'MAHONEY, Wyoming HERMAN WELKER, Idaho MATTHEW M. NEELY, West Virginia JOHN MARSHALL BUTLER, Maryland Subcommittee To Investigate the Administration of the Internal Security Act and Other Internal Security Laws JAMES O. EASTLAND, Mississippi, Chairman OLIN D. JOHNSTON, South Carolina WILLIAM E. JENNER, Indiana JOHN L. McCLELLAN, Arkansas ARTHUR V. WATKINS, Utah THOMAS C. HENNINGS, Jr., Missouri HERMAN WELKER, Idaho PRICE DANIEL, Texas JOHN MARSHALL BUTLER, Maryland Robert Morris, Chief Counsel William A. Rosher, Administrative Counsel Benjamin Mandel, Director of Research n CONTENTS Witnesses : Page Dodd, Bella V 1467 Munsell, Alexander E. O 1463 APPENDIX The career of J. Peters 1483 in SCOPE OF SOVIET ACTIVITY IN THE UNITED STATES TUESDAY, JUNE 12, 1956 United States Senate, Subcommittee To Investigate the Administration of the Internal Security Act and Other Internal Security Laws of the Committee on the Judiciary, Washington, D. -

The University of Arizona

Erskine Caldwell, Margaret Bourke- White, and the Popular Front (Moscow 1941) Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Caldwell, Jay E. Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 05/10/2021 10:56:28 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/316913 ERSKINE CALDWELL, MARGARET BOURKE-WHITE, AND THE POPULAR FRONT (MOSCOW 1941) by Jay E. Caldwell __________________________ Copyright © Jay E. Caldwell 2014 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2014 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Dissertation Committee, we certify that we have read the dissertation prepared by Jay E. Caldwell, titled “Erskine Caldwell, Margaret Bourke-White, and the Popular Front (Moscow 1941),” and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ________________________________________________ Date: 11 February 2014 Dissertation Director: Jerrold E. Hogle _______________________________________________________________________ Date: 11 February 2014 Daniel F. Cooper Alarcon _______________________________________________________________________ Date: 11 February 2014 Jennifer L. Jenkins _______________________________________________________________________ Date: 11 February 2014 Robert L. McDonald _______________________________________________________________________ Date: 11 February 2014 Charles W. Scruggs Final approval and acceptance of this dissertation is contingent upon the candidate’s submission of the final copies of the dissertation to the Graduate College.