Conference Papers the Future of the House of Lords

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Father of the House Sarah Priddy

BRIEFING PAPER Number 06399, 17 December 2019 By Richard Kelly Father of the House Sarah Priddy Inside: 1. Seniority of Members 2. History www.parliament.uk/commons-library | intranet.parliament.uk/commons-library | [email protected] | @commonslibrary Number 06399, 17 December 2019 2 Contents Summary 3 1. Seniority of Members 4 1.1 Determining seniority 4 Examples 4 1.2 Duties of the Father of the House 5 1.3 Baby of the House 5 2. History 6 2.1 Origin of the term 6 2.2 Early usage 6 2.3 Fathers of the House 7 2.4 Previous qualifications 7 2.5 Possible elections for Father of the House 8 Appendix: Fathers of the House, since 1901 9 3 Father of the House Summary The Father of the House is a title that is by tradition bestowed on the senior Member of the House, which is nowadays held to be the Member who has the longest unbroken service in the Commons. The Father of the House in the current (2019) Parliament is Sir Peter Bottomley, who was first elected to the House in a by-election in 1975. Under Standing Order No 1, as long as the Father of the House is not a Minister, he takes the Chair when the House elects a Speaker. He has no other formal duties. There is evidence of the title having been used in the 18th century. However, the origin of the term is not clear and it is likely that different qualifications were used in the past. The Father of the House is not necessarily the oldest Member. -

'The Left's Views on Israel: from the Establishment of the Jewish State To

‘The Left’s Views on Israel: From the establishment of the Jewish state to the intifada’ Thesis submitted by June Edmunds for PhD examination at the London School of Economics and Political Science 1 UMI Number: U615796 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U615796 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 F 7377 POLITI 58^S8i ABSTRACT The British left has confronted a dilemma in forming its attitude towards Israel in the postwar period. The establishment of the Jewish state seemed to force people on the left to choose between competing nationalisms - Israeli, Arab and later, Palestinian. Over time, a number of key developments sharpened the dilemma. My central focus is the evolution of thinking about Israel and the Middle East in the British Labour Party. I examine four critical periods: the creation of Israel in 1948; the Suez war in 1956; the Arab-Israeli war of 1967 and the 1980s, covering mainly the Israeli invasion of Lebanon but also the intifada. In each case, entrenched attitudes were called into question and longer-term shifts were triggered in the aftermath. -

"The Problem of Predicting What Will Last"

Allan Massie, "The Problem of Predicting What Will Last" Booksonline, with Amazon.co.uk (An Electronic Telegraph Publication) 4 January 2000 As our Book of the Century series concludes, Allan Massie compares the list with one published by The Daily Telegraph 100 years ago EACH WEEK for the past two years The Daily Telegraph’s literary editor has asked a contributor to name and describe his or her "Book of the Century", and today the series concludes with Arthur C. Clarke’s choice. The full selection invites comparison with a list drawn up by The Telegraph a century ago; we print both here. The comparison cannot, however, be exact. All the books chosen in 1899 were fiction - the paper offered its readers the "100 Best Novels in the World", selected by the editor "with the assistance of Sir Edwin Arnold, K. C. I. E, H. D. Traill, D. C. L, and W. L. Courtney, LL. D.". The modern list includes poetry, plays, history, diaries, philosophy, economics, memoirs, biography and travel writing. It is certainly eclectic, ranging from Wittgenstein’s Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, selected by David Sylvester, to The Wind in the Willows, chosen by John Bayley, and Down with Skool, Wendy Cope’s Book of the Century. The 1899 list, on offer at the time in a cloth-bound edition at nine guineas the lot (easy terms available), is homogeneous, as the modern one is not, not only because it consists entirely of works of fiction but also because the selection was made by a small group. And since they were picking the 100 Best Novels, they were able to include books that nobody might name as a single "Book of the Century" but which many might put in their top 20 or so. -

New Labour, Old Morality

New Labour, Old Morality. In The IdeasThat Shaped Post-War Britain (1996), David Marquand suggests that a useful way of mapping the „ebbs and flows in the struggle for moral and intellectual hegemony in post-war Britain‟ is to see them as a dialectic not between Left and Right, nor between individualism and collectivism, but between hedonism and moralism which cuts across party boundaries. As Jeffrey Weeks puts it in his contribution to Blairism and the War of Persuasion (2004): „Whatever its progressive pretensions, the Labour Party has rarely been in the vanguard of sexual reform throughout its hundred-year history. Since its formation at the beginning of the twentieth century the Labour Party has always been an uneasy amalgam of the progressive intelligentsia and a largely morally conservative working class, especially as represented through the trade union movement‟ (68-9). In The Future of Socialism (1956) Anthony Crosland wrote that: 'in the blood of the socialist there should always run a trace of the anarchist and the libertarian, and not to much of the prig or the prude‟. And in 1959 Roy Jenkins, in his book The Labour Case, argued that 'there is a need for the state to do less to restrict personal freedom'. And indeed when Jenkins became Home Secretary in 1965 he put in a train a series of reforms which damned him in they eyes of Labour and Tory traditionalists as one of the chief architects of the 'permissive society': the partial decriminalisation of homosexuality, reform of the abortion and obscenity laws, the abolition of theatre censorship, making it slightly easier to get divorced. -

Middle East Policy – Some Alternative Views 47

Kaufman Galloway 10/12/05 2:53 AM Page 45 45 Middle East I Jeremy Corbyn (Islington, North) (Labour): Policy … The war in Iraq has cost the lives of at least Some Alternative 500,000 people since 2003. The Saddam Hussein regime cost the lives of many tens of Views thousands of Iraqis before that. My right hon. Friend the Member for Cynon Valley (Ann Clwyd) was right to highlight the horrors of Jeremy Corbyn MP Saddam Hussein’s regime. A small number of Gerald Kaufman MP us, including my right hon. Friend, opposed it from the 1980s onwards, when the House was George Galloway MP busy turning a blind eye to arms sales, oil deals and all the other support that was given to that regime because it suited the west to support Iraq in the war against Iran. However, I differ from my right hon. Friend the Member for Cynon Valley about where we go from here. It cannot be said that the position in Iraq is better now than in the latter days of Saddam Hussein. As I said, more than 500,000 have already been killed. According to a BBC website, 1.7 million Iraqis have been forced immediately into exile and all the neighbouring countries are threatening to close their borders. Harry Cohen (Leyton and Wanstead) (Labour): I want to correct my hon. Friend. I saw the BBC website, and it said that 2 million On 24 January 2007, the Iraqis had fled the country. The figure of 1.7 House of Commons debated million related to internally displaced people. -

House of Commons Monday 27 February 2017 Votes and Proceedings

No. 115 1 House of Commons Monday 27 February 2017 Votes and Proceedings The House met at 2.30 pm. PRAYERS. 1 Death of a Member (Father of the House) The Speaker made the following communication to the House: It is with great sadness that I have to report to the House the death of the right hon. Sir Gerald Kaufman, Labour Member of Parliament for Manchester Gorton. He will be sorely missed by his relatives, by his friends, by his constituents and by his parliamentary colleagues, not to mention very large numbers of people across this country and around the world. Colleagues, before Gerald entered Parliament, and after leaving Leeds Grammar School and Oxford University, Gerald worked as assistant general secretary of the Fabian Society and subsequently as a journalist on the Daily Mirror and for the New Statesman. Thereafter, he was parliamentary press liaison officer for the Labour party, working closely with Harold Wilson. He entered this House, as colleagues will know, in June 1970, as the Member of Parliament for Manchester, Ardwick, which constituency he represented until 1983. Thereafter, and following boundary changes, he represented Manchester Gorton from 1983 without interruption. He was, as we know, the Father of the House. He served in this place diligently, with principle and utter dedication, for well over 46 years. Under Harold Wilson and Jim Callaghan, Gerald served as a Minister with responsibility for the environment and subsequently with responsibility for industry. In opposition, he was a long-serving and distinguished member of Labour’s shadow Cabinet, serving as shadow Secretary of State for the Environment, as shadow Home Secretary and, indeed, as shadow Foreign Secretary. -

Terrorism Knows No Borders

TERRORISM TERRORISM TERRORISM TERRORISM KNOWS KNOWS KNOWS KNOWS NO BORDERS NO BORDERS NO BORDERS NO BORDERS TERRORISM TERRORISM TERRORISM TERRORISM KNOWS KNOWS KNOWS KNOWS NO BORDERS NO BORDERS NO BORDERS NO BORDERS TERRORISM TERRORISM TERRORISM TERRORISM KNOWS KNOWS KNOWS KNOWS NO BORDERS NO BORDERS NO BORDERS NO BORDERS TERRORISM TERRORISM TERRORISM TERRORISM KNOWS KNOWS KNOWS KNOWS NO BORDERS NO BORDERS NO BORDERS NO BORDERS TERRORISM TERRORISM TERRORISM TERRORISM KNOWS KNOWS KNOWS KNOWS NO BORDERS NO BORDERS NO BORDERS NO BORDERS October 2019 his is a special initiative for SEFF to be associated with, it is one part of a three part overall Project which includes; the production of a Book and DVD Twhich captures the testimonies and experiences of well over 20 innocent victims and survivors of terrorism from across Great Britain and The Republic of Ireland. The Project title; ‘Terrorism knows NO Borders’ aptly illustrates the broader point that we are seeking to make through our involvement in this work, namely that in the context of Northern Ireland terrorism and criminal violence was not curtailed to Northern Ireland alone but rather that individuals, families and communities experienced its’ impacts across the United Kingdom, Republic of Ireland and beyond these islands. This Memorial Quilt Project does not claim to represent the totality of lives lost across Great Britain and The Republic of Ireland but rather seeks to provide some understanding of the sacrifices paid by communities, families and individuals who have been victimised by ‘Republican’ or ‘Loyalist’ terrorism. SEFF’s ethos means that we are not purely concerned with victims/survivors who live within south Fermanagh or indeed the broader County. -

Catalogue 1949-1987

Penguin Specials 1949-1987 for his political activities and first became M.P. for West Fife in 1935. S156-S383 Penguin Specials. Before the war, when books could be produced quickly, we used to publish S156 1949 The case for Communism. volumes of topical interest as Penguin Specials. William Gallacher We are now able to resume this policy of Specially written for and first published in stimulating public interest in current problems Penguin Books February 1949 and controversies, and from time to time we pp. [vi], [7], 8-208. Inside front cover: About this shall issue books which, like this one, state the Book. Inside rear cover: note about Penguin case for some contemporary point of view. Other Specials [see below] volumes pleading a special cause or advocating a Printers: The Philips Park Press, C.Nicholls and particular solution of political, social and Co. Ltd, London, Manchester, Reading religious dilemmas will appear at intervals in this Price: 1/6d. new series of post-war Penguin Specials ... Front cover: New Series Number One. ... As publishers we have no politics. Some time ago S157 1949 I choose peace. K. Zilliacus we invited a Labour M.P. and a Conservative Specially written for and first published in M.P. to affirm the faith and policy of the two Penguin Books October 1949 principal parties and they did so in two books - pp. [x], [11], 12-509, [510] blank + [2]pp. ‘Labour Marches On’, by John Parker M.P., and adverts. for Penguin Books. Inside front cover ‘The Case for Conservatism’, by Quintin Hogg, [About this Book]. -

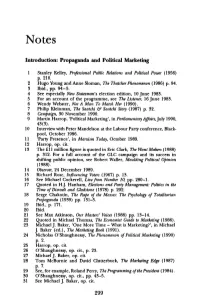

Introduction: Propaganda and Political Marketing

Notes Introduction: Propaganda and Political Marketing 2 Stanley Kelley, Professional Public Relations and Political Power (1956) p. 210. 2 Hugo Young and Anne Sloman, The Thatcher Phenomenon (1986) p. 94. 3 Ibid., pp. 94-5. 4 See especially New Statesman's election edition, 10 June 1983. 5 For an account of the programme, see The Listmer, 16 June 1983. 6 Wendy Webster, Not A Man To Matcll Her (1990). 7 Philip Kleinman, The Saatchi & Saatchi Story (1987) p. 32. 8 Campaign, 30 November 1990. 9 Martin Harrop, 'Political Marketing', in ParliamentaryAffairs,July 1990, 43(3). 10 Interview with Peter Mandelson at the Labour Party conference, Black- pool, October 1986. 11 'Party Presence', in Marxism Today, October 1989. 12 Harrop, op. cit. 13 The £11 million figure is quoted in Eric Clark, The Want Makers (1988) p. 312. For a full account of the GLC campaign and its success in shifting public opinion, see Robert Waller, Moulding Political Opinion (1988). 14 Obse1ver, 24 December 1989. 15 Richard Rose, Influencing Voters (1967) p. 13. 16 See Michael Cockerell, Live from Number 10, pp. 280-1. 17 Quoted in HJ. Hanham, Ekctions and Party Management: Politics in the Time of Disraeli and Gladstone ( 1978) p. 202. 18 Serge Chakotin, The Rape of the Masses: The Psychology of Totalitarian Propaganda (1939) pp. 131-3. 19 Ibid., p. 171. 20 Ibid. 21 See Max Atkinson, Our Masters' Voices (1988) pp. 13-14. 22 Quoted in Michael Thomas, The Economist Guide to Marketing (1986). 23 Michael J. Baker, 'One More Time- What is Marketing?', in Michael J. -

Chapter 2. 1979-83: Weak Agency and Labour's Electoral Nadir

Chapter 2. 1979-83: Weak Agency and Labour’s Electoral Nadir Introduction The period from 1979 to 1983 represented, in more ways than one, a nadir for the Labour Party. The 1974-9 government was brought down on a vote of no confidence following a winter of industrial action. Many felt that Callaghan should have called the election in late 1978, when Labour’s electoral prospects seemed better, and in hindsight it appears difficult to disagree. Nonetheless, on May 3, 1979, the Conservative Party won a majority of 43 seats in the House of Commons, and Margaret Thatcher became Britain’s first woman prime minister. Table 2.1: British General Election Results, 1979 and 1983.1 Party MPs % Share of Votes 1979 1983 1979 1983 Conservative 339 397 43.9 42.4 Labour 269 209 36.9 27.6 Lib/SDP Alliance 11 23 13.8 25.4 Plaid Cymru 2 2 0.4 0.4 Scottish National Party 2 2 1.6 1.1 Others 12 17 3.4 3.1 Total 635 650 100.0 100.0 Within the next four years things went from bad to worse for Labour. The Party experienced a period of intense in-fighting which undermined the Party’s credibility and led to the creation in 1981 of a new centre-left party in the shape of the Social Democratic Party (SDP). At the 1983 general election, as Table 2.1 shows, the Party barely managed to finish in second place behind the Conservatives in terms of votes won, and had its worst electoral performance (in terms of its share of total votes cast) since the First World War. -

Holders of Ministerial Office in the Conservative Governments 1979-1997

Holders of Ministerial Office in the Conservative Governments 1979-1997 Parliamentary Information List Standard Note: SN/PC/04657 Last updated: 11 March 2008 Author: Department of Information Services All efforts have been made to ensure the accuracy of this data. Nevertheless the complexity of Ministerial appointments, changes in the machinery of government and the very large number of Ministerial changes between 1979 and 1997 mean that there may be some omissions from this list. Where an individual was a Minister at the time of the May 1997 general election the end of his/her term of office has been given as 2 May. Finally, where possible the exact dates of service have been given although when this information was unavailable only the month is given. The Parliamentary Information List series covers various topics relating to Parliament; they include Bills, Committees, Constitution, Debates, Divisions, The House of Commons, Parliament and procedure. Also available: Research papers – impartial briefings on major bills and other topics of public and parliamentary concern, available as printed documents and on the Intranet and Internet. Standard notes – a selection of less formal briefings, often produced in response to frequently asked questions, are accessible via the Internet. Guides to Parliament – The House of Commons Information Office answers enquiries on the work, history and membership of the House of Commons. It also produces a range of publications about the House which are available for free in hard copy on request Education web site – a web site for children and schools with information and activities about Parliament. Any comments or corrections to the lists would be gratefully received and should be sent to: Parliamentary Information Lists Editor, Parliament & Constitution Centre, House of Commons, London SW1A OAA. -

MS 254 A980 Women's Campaign for Soviet Jewry 1

1 MS 254 A980 Women’s Campaign for Soviet Jewry 1 Administrative papers Parliamentary Correspondence Correspondence with Members of Parliament 1/1/1 Members of Parliament correspondence regarding support for the 1978-95 efforts of the Women’s Campaign for Soviet Jewry and brief profiles and contact details for individual Members of Parliament; Diane Abbot, Robert Adley, Jonathan Aitken, Richard Alexander, Michael Alison, Graham Allen, David Alton, David Amess, Donald Anderson, Hilary Armstrong, Jacques Arnold, Tom Arnold, David Ashby, Paddy Ashdown, Joe Ashton, Jack Aspinwall, Robert Atkins, and David Atkinson 1/1/2 Members of Parliament correspondence regarding support for the 1974-93 efforts of the Women’s Campaign for Soviet Jewry and brief profiles and contact details for individual Members of Parliament; Kenneth Baker, Nicholas Baker, Tony Baldry, Robert Banks, Tony Banks, Kevin Barron, Spencer Batiste and J. D. Battle 1/1/3 Members of Parliament correspondence regarding support for the 1974-93 efforts of the Women’s Campaign for Soviet Jewry and brief profiles and contact details for individual Members of Parliament; Margaret Beckett, Roy Beggs, Alan James Beith, Stuart Bell, Henry Bellingham, Vivian Bendall, Tony Benn, Andrew F. Bennett, Gerald Bermingham, John Biffen, John Blackburn, Anthony Blair, David Blunkett, Paul Boateng, Richard Body, Hartley Booth, Nichol Bonsor, Betty Boothroyd, Tim Boswell and Peter Bottomley 1/1/4 Members of Parliament correspondence regarding support for the 1975-94 efforts of the Women’s Campaign