Thumbnail Sketches of Freedom Fighters 193

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bibliography

BIbLIOGRAPHY 2016 AFI Annual Report. (2017). Alliance for Financial Inclusion. Retrieved July 31, 2017, from https://www.afi-global.org/sites/default/files/publica- tions/2017-05/2016%20AFI%20Annual%20Report.pdf. A Law of the Abolition of Currencies in a Small Denomination and Rounding off a Fraction, July 15, 1953, Law No.60 (Shōgakutsūka no seiri oyobi shiharaikin no hasūkeisan ni kansuru hōritsu). Retrieved April 11, 2017, from https:// web.archive.org/web/20020628033108/http://www.shugiin.go.jp/itdb_ housei.nsf/html/houritsu/01619530715060.htm. About PBC. (2018, August 21). The People’s Bank of China. Retrieved August 21, 2018, from http://www.pbc.gov.cn/english/130712/index.html. About Us. Alliance for Financial Inclusion. Retrieved July 31, 2017, from https:// www.afi-global.org/about-us. AFI Official Members. Alliance for Financial Inclusion. Retrieved July 31, 2017, from https://www.afi-global.org/sites/default/files/inlinefiles/AFI%20 Official%20Members_8%20February%202018.pdf. Ahamed, L. (2009). Lords of Finance: The Bankers Who Broke the World. London: Penguin Books. Alderman, L., Kanter, J., Yardley, J., Ewing, J., Kitsantonis, N., Daley, S., Russell, K., Higgins, A., & Eavis, P. (2016, June 17). Explaining Greece’s Debt Crisis. The New York Times. Retrieved January 28, 2018, from https://www.nytimes. com/interactive/2016/business/international/greece-debt-crisis-euro.html. Alesina, A. (1988). Macroeconomics and Politics (S. Fischer, Ed.). NBER Macroeconomics Annual, 3, 13–62. Alesina, A. (1989). Politics and Business Cycles in Industrial Democracies. Economic Policy, 4(8), 57–98. © The Author(s) 2018 355 R. Ray Chaudhuri, Central Bank Independence, Regulations, and Monetary Policy, https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-58912-5 356 BIBLIOGRAPHY Alesina, A., & Grilli, V. -

International Conference on Asian Art, Culture and Heritage

Abstract Volume: International Conference on Asian Art, Culture and Heritage International Conference of the International Association for Asian Heritage 2011 Abstract Volume: Intenational Conference on Asian Art, Culture and Heritage 21th - 23rd August 2013 Sri Lanka Foundation, Colombo, Sri Lanka Editor Anura Manatunga Editorial Board Nilanthi Bandara Melathi Saldin Kaushalya Gunasena Mahishi Ranaweera Nadeeka Rathnabahu iii International Conference of the International Association for Asian Heritage 2011 Copyright © 2013 by Centre for Asian Studies, University of Kelaniya, Sri Lanka. First Print 2013 Abstract voiume: International Conference on Asian Art, Culture and Heritage Publisher International Association for Asian Heritage Centre for Asian Studies University of Kelaniya, Sri Lanka. ISBN 978-955-4563-10-0 Cover Designing Sahan Hewa Gamage Cover Image Dwarf figure on a step of a ruined building in the jungle near PabaluVehera at Polonnaruva Printer Kelani Printers The views expressed in the abstracts are exclusively those of the respective authors. iv International Conference of the International Association for Asian Heritage 2011 In Collaboration with The Ministry of National Heritage Central Cultural Fund Postgraduate Institute of Archaeology Bio-diversity Secratariat, Ministry of Environment and Renewable Energy v International Conference of the International Association for Asian Heritage 2011 Message from the Minister of Cultural and Arts It is with great pleasure that I write this congratulatory message to the Abstract Volume of the International Conference on Asian Art, Culture and Heritage, collaboratively organized by the Centre for Asian Studies, University of Kelaniya, Ministry of Culture and the Arts and the International Association for Asian Heritage (IAAH). It is also with great pride that I join this occasion as I am associated with two of the collaborative bodies; as the founder president of the IAAH, and the Minister of Culture and the Arts. -

The President of India, Rajendra Prasad, Bade Horace Alexander Farewell at A

FEBRUARY-MARCH 1952 The annual regional meeting for the AFSC will be held in three cities to allow maximum participation by members of the widespread Regional Committee and all other interested persons. Sessions in Dallas, Houston, and Austin will follow the same general program. Attenders ,./! are invited not only from these cities but from the vicinity. Of widest appeal will probably be the 8 p.m. meeting, offering "A Look at Europe and a Look at Asia." Olcutt The President of India, RaJendra Prasad, Sanders will report on his recent six bade Horace Alexander farewell at a spe months of visiting Quaker centers in cial reception in :ryew Delhi a few months Europe. Horace Alexander, for many ago. years director of the Quaker center in Delhi, India, will analyze the situation in Asia. A 6 p.m. supper meeting invites dis Horace Alexander, an English Friend cussion of developments in youth proj with long experience in India, will speak ects, employment on merit, and :peace at the annual regional AFSC meetings in education. More formal reports of nomi Dallas, Houston, and Austin. He will also nating, personnel, and finance committees speak at Corpus Christi at the Oak Park will come at 5 p.m. Methodist Church Sunday morning~ Feb ruary 24~ His address will be broadcasto DALLAS: WEDNESDAY, FEBRUARY 20 5 p.m. report meeting and 6 p.m. pot · He lectured in international relations luck supper at the new AFSC office, 2515 at Woodbrook College from 1919 to 1944. McKinney; phone Sterling 4691 for sug During visits to India in 1927 and 1930 he gestions of what you might bring. -

Goa Government Of

IReg. No. GR/RNP/GOAl3ZI I RNINo.GOAENG/2002/6410 I Panaji. 27th January, 2005 (Magha 7, 1926) SERIES III N~ .. 44 OFFICIAL GAZETTE r GOVERNMENT OF GOA GOVERNMENT OF GOA Registration of Tourist Trade Act, 1982, is. hereby • cancelled as the said Tourist Taxi -has been converted Department of Tourism into a private vehicle with effect from 20-12-2002, Directorate of Tourism bearing No. GA-Ol/R-3879. Panaji, 7th December, 2004.- The Director of Order Tourism & Prescribed Authority, A. C. Pereira. No. 5/S(4-694)/2004-DT/2124 The Registration of Tourist· Thxi No. GA-02/V-2123 Or.der belonging to Shri Filipe Pereira, H. No. 286, Benaulim, No. 5/S(4-1501)/2004'DT/2158 Salcete Goa, ':'nder the Goa Registration of Tourist Trade Act, 1982, entered in register NO ... 15 at page The Registration of Tourist Thxi No. GA-02/U-3237 No.5 is hereby cancelled as the said Tourist Thxi has belonging to Shri Anthony M. Fernandes, H. No. 516, been conyerted into a ·private vehicle with effect from Curilo, Majorda, Salcete Goa, under the Goa 28-06-2004, bearing No. GA-08/A-2707. Registration of Tourist Trade Act, 1982, entered in register No. 21 at page No. 87 is hereby cancelled as Panaji, 7th December, 2004.-,. The Director. of the said Tourist Taxi has' been converted into a Tourism & Prescribed'Authority, A. C. Pereira. private vehicle with effect from 10-07-2004, bearing No. GA-Ol/C-7877. Panaji, 7th December, 2004.- The Director of Order Tourism & Prescribed Authority, A. -

School of Oriental and African Studies)

BRITISH ATTITUDES T 0 INDIAN NATIONALISM 1922-1935 by Pillarisetti Sudhir (School of Oriental and African Studies) A thesis submitted to the University of London for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 1984 ProQuest Number: 11010472 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 11010472 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 2 ABSTRACT This thesis is essentially an analysis of British attitudes towards Indian nationalism between 1922 and 1935. It rests upon the argument that attitudes created paradigms of perception which condi tioned responses to events and situations and thus helped to shape the contours of British policy in India. Although resistant to change, attitudes could be and were altered and the consequent para digm shift facilitated political change. Books, pamphlets, periodicals, newspapers, private papers of individuals, official records, and the records of some interest groups have been examined to re-create, as far as possible, the structure of beliefs and opinions that existed in Britain with re gard to Indian nationalism and its more concrete manifestations, and to discover the social, political, economic and intellectual roots of the beliefs and opinions. -

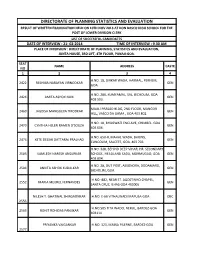

Directorate of Planning Statistics and Evaluation

DIRECTORATE OF PLANNING STATISTICS AND EVALUATION RESULT OF WRITTEN EXAMINATION HELD ON 10TH NOV 2013 AT DON BASCO HIGH SCHOOL FOR THE POST OF LOWER DIVISION CLERK LIST OF SUCCESSFUL CANDIDATES DATE OF INTERVIEW : 21- 02-2014 TIME OF INTERVIEW : 9.30 AM PLACE OF INTERVIEW : DIRECTORATE OF PLANNING, STATISTICS AND EVALUATION, JUNTA HOUSE, 3RD LIFT, 4TH FLOOR, PANAJI-GOA. SEAT NAME ADDRESS CASTE NO 1 2 3 4 H.NO. 18, GIRKAR WADA, HARMAL, PERNEM, 2422 RESHMA NARAYAN VIRNODKAR GEN GOA. H.NO. 286, KUMYAMAL, SAL, BICHOLIM, GOA 2424 AMITA ASHOK NAIK GEN 403 503. MAULI PRASAD BLDG, 2ND FLOOR, MANGOR 2460 JAGDISH MANGUEXA TIRODKAR GEN HILL, VASCO DA GAMA , GOA 403 802. H.NO. 18, BHAGWATI ENCLAVE, CHIMBEL, GOA 2470 CYNTHIA HELEN RAMEN D'SOUZA GEN 403 006. H.NO. 650-II, MAHAL WADA, BHIUNS, 2474 XETE DESSAI DATTARAJ PRALHAD GEN CUNCOLIM, SALCETE, GOA. 403 703. H.NO. 328, BEHIND DEEP VIHAR, HR. SECONDARY 2503 KAMLESH NARESH ANSURKAR SCHOOL, HEADLAND SADA, MORMUGAO, GOA GEN 403 804. H.NO. 28, OUT POST, ASSONORA, DODAMARG, 2504 ANKITA ASHOK KUDALKAR GEN BICHOLIM, GOA. H.NO.-882, NEAR ST. AGOSTINHO CHAPEL, 2552 MARIA MEUREL FERNANDES GEN SANTA CRUZ, ILHAS-GOA 403005 NILESH T. GHATWAL SHIRGAONKAR H.NO. E-66 VITHALWADI MAPUSA-GOA OBC 2556 H.NO.505 TITA WADO, NERUL, BARDEZ-GOA 2563 ROHIT ROHIDAS PANJIKAR GEN 403114 PRIYANKA VAIGANKAR H.NO. 323, MAINA PILERNE, BARDEZ-GOA GEN 2577 H.NO. 85/A, MASTIMOL, CANACONA GOA 2587 RINA M. KIRLOSKAR GEN 403702 2589 RAJESH A. PRABHU DESAI H.NO. 508, MALVEMOL-COLA, CANACONA- GOA GEN JAIRAM COMPLEX, A-1 BLDG. -

Hungry Bengal: War, Famine, Riots, and the End of Empire 1939-1946

Hungry Bengal: War, Famine, Riots, and the End of Empire 1939-1946 By Janam Mukherjee A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Anthropology and History) In the University of Michigan 2011 Doctoral Committee: Professor Barbara D. Metcalf, Chair Emeritus Professor David W. Cohen Associate Professor Stuart Kirsch Associate Professor Christi Merrill 1 "Unknown to me the wounds of the famine of 1943, the barbarities of war, the horror of the communal riots of 1946 were impinging on my style and engraving themselves on it, till there came a time when whatever I did, whether it was chiseling a piece of wood, or burning metal with acid to create a gaping hole, or cutting and tearing with no premeditated design, it would throw up innumerable wounds, bodying forth a single theme - the figures of the deprived, the destitute and the abandoned converging on us from all directions. The first chalk marks of famine that had passed from the fingers to engrave themselves on the heart persist indelibly." 2 Somnath Hore 1 Somnath Hore. "The Holocaust." Sculpture. Indian Writing, October 3, 2006. Web (http://indianwriting.blogsome.com/2006/10/03/somnath-hore/) accessed 04/19/2011. 2 Quoted in N. Sarkar, p. 32 © Janam S. Mukherjee 2011 To my father ii Acknowledgements I would like to thank first and foremost my father, Dr. Kalinath Mukherjee, without whom this work would not have been written. This project began, in fact, as a collaborative effort, which is how it also comes to conclusion. His always gentle, thoughtful and brilliant spirit has been guiding this work since his death in May of 2002 - and this is still our work. -

The Religious Lifeworlds of Canada's Goan and Anglo-Indian Communities

Brown Baby Jesus: The Religious Lifeworlds of Canada’s Goan and Anglo-Indian Communities Kathryn Carrière Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the PhD degree in Religion and Classics Religion and Classics Faculty of Arts University of Ottawa © Kathryn Carrière, Ottawa, Canada, 2011 I dedicate this thesis to my husband Reg and our son Gabriel who, of all souls on this Earth, are most dear to me. And, thank you to my Mum and Dad, for teaching me that faith and love come first and foremost. Abstract Employing the concepts of lifeworld (Lebenswelt) and system as primarily discussed by Edmund Husserl and Jürgen Habermas, this dissertation argues that the lifeworlds of Anglo- Indian and Goan Catholics in the Greater Toronto Area have permitted members of these communities to relatively easily understand, interact with and manoeuvre through Canada’s democratic, individualistic and market-driven system. Suggesting that the Catholic faith serves as a multi-dimensional primary lens for Canadian Goan and Anglo-Indians, this sociological ethnography explores how religion has and continues affect their identity as diasporic post- colonial communities. Modifying key elements of traditional Indian culture to reflect their Catholic beliefs, these migrants consider their faith to be the very backdrop upon which their life experiences render meaningful. Through systematic qualitative case studies, I uncover how these individuals have successfully maintained a sense of security and ethnic pride amidst the myriad cultures and religions found in Canada’s multicultural society. Oscillating between the fuzzy boundaries of the Indian traditional and North American liberal worlds, Anglo-Indians and Goans attribute their achievements to their open-minded Westernized upbringing, their traditional Indian roots and their Catholic-centred principles effectively making them, in their opinions, admirable models of accommodation to Canada’s system. -

General Body Minutes 28-06-2018

MINUTES OF THE GENERAL BODY MEETING OF THE BOARD CONVENED ON 28/06/2018 AT 10.00 A.M. IN THE CONFERENCE HALL OF THE DIRECTORATE OF EDUCATION, PORVORIM- GOA The following Members attended the meeting:- 1. Shri. Ramkrishna Samant – Chairman 15. Shri. Hemant Madhusudan Kamat 2. Dr. Uday Gaunkar- Vice Chairman 16. Shri. Conrad C. Mendes 3. Director of Skill Development & 17. Shri. Shashikant K. Punaji Entrepreneurship 18. Shri. Pandurang J. Prabhudessai 4. Director, State Council of Educational 19. Shri. Sanjay Naik Research & Training. 20. Shri. Oscar A. A. Da Costa 5. Dr. Satish Hari Prabhu Keluskar 21. Shri. Mahesh Pandhari Bhagat 6. Prof. Vrushali Mandrekar 22. Smt. Miriam Ann Duarte 7. Dr. Nandkumar M. Kamat 23. Shri. Gopal Prabhu 8. Shri. Ramdas V. Kelkar 24. Shri. Parshuram N Gawade 9. Shri. Walter A. S. Cabral 25. Shri. Devanand S. Satarkar 10. Dr. Celsa Pinto 26. Shri. Dilesh Gadekar 11. Shri. Damodar Guna Phadte 27. Smt. Maria B. D. A. Pereira 12. Shri. Sudan Fati Naik Gaonkar 28. Shri. Nagendra D. Kore 13. Smt. Maria Gorette Alphonso Shri. Bhagirath G. Shetye - 14. Shri. Joseph J. V. R. Coutinho Secretary Leave of absence was granted to following Members as per their request:- 1. Hon. MLA Shri. Nilesh Cabral 2. Director of School Education 3. Dr. Allan Abreo Joseph 4. Dr. Sadanand Hinde 5. Shri. Mahesh Vengurlekar The following members did not attend the meeting:- 1. Hon. MLA. Shri. Dayanand Sopte 2. Director of Higher Education 3. Director of Technical Education 4. Director of Sports & Youth Affairs 5. Director of Art and Culture 6. -

GOA and PORTUGAL History and Development

XCHR Studies Series No. 10 GOA AND PORTUGAL History and Development Edited by Charles J. Borges Director, Xavier Centre of Historical Research Oscar G. Pereira Director, Centro Portugues de Col6nia, Univ. of Cologne Hannes Stubbe Professor, Psychologisches Institut, Univ. of Cologne CONCEPT PUBLISHING COMPANY, NEW DELHI-110059 ISBN 81-7022-867-0 First Published 2000 O Xavier Centre of Historical Research Printed and Published by Ashok Kumar Mittal Concept Publishing Company A/15-16, Commercial Block, Mohan. Garden New Delhi-110059 (India) Phones: 5648039, 5649024 Fax: 09H 11 >-5648053 Email: [email protected] 4 Trade in Goa during the 19th Century with Special Reference to Colonial Kanara N . S hyam B hat From the arrival of the Portuguese to the end of the 18Ih century, the economic history of Portuguese Goa is well examined by historians. But not many works are available on the economic history of Goa during the 19lh and 20lh centuries, which witnessed considerable decline in the Portuguese trade in India. This, being a desideratum, it is not surprising to note that a study of the visible trade links between Portuguese Goa and the coastal regions of Karnataka1 is not given serious attention by historians so far. Therefore, this is an attempt to analyse the trade connections between Portuguese Goa and colonial Kanara in the 19lh century.2 The present exposition is mainly based on the administrative records of the English East India Company government such as Proceedings of the Madras Board of Revenue, Proceedings of the Madras Sea Customs Department, Madras Commercial Consultations, and official letters of the Collectors of Kanara. -

Alexander Cowan Wilson 1866-1955

Alexander Cowan Wilson 1866-1955 his finances and his causes By STEPHEN WILSON FRIENDS HISTORICAL SOCIETY FRIENDS HOUSE, EUSTON ROAD, LONDON NWi 2BJ 1974 This paper was delivered as a Presidential Address to the Friends Historical Society at a meeting held at Friends House on 2 November 1973. Friends Historical Society is grateful for a special contribution which has enabled the paper to be published. Supplement No. 35 to the Journal of the Friends Historical Society © Friends Historical Society 1974 Obtainable from Friends Book Centre, Friends House, Euston Road, London NWi 2BJ, and Friends Book Store, 302 Arch Street, Philadelphia, Pa 19106, USA PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN BY HEADLEY BROTHERS LTD IO9 KINGSWAY LONDON WC2B 6PX AND ASHFORD KENT s-.. - , ^Wff^m^:^:ty-is V --*;• '< •*••«^< >v3?'V '- . •. 7 •*,.!, J^J .1 v^-.'--•• . i" ^.;;^ •• . ^ ;->@^^?f^-.!C1::- & ALEXANDER C. WILSON (1866-1055) aged about 55 ALEXANDER COWAN WILSON 1866-1955: HIS FINANCES AND HIS CAUSES. 1! initial explanation should be given for selecting my subject—some account of the life of my father, to whom A I shall refer as ACW, and his wife EJW. Primarily it is a subject with which I had an intimate acquaintance over a period of fifty years, and which therefore has involved a minimum of original research. But apart from this it may I think be useful to record a few of the circumstances in which he grew up two and three generations ago, and to mention some of those concerns and interests which he and various of his contemporaries regarded as important, which frequently interlocked with Quaker traditions and activities, and which collectively formed part of the dissenting and radical streams of thought and outlook which influence society. -

FORM 9 List of Applications for Inclusion Received in Form 6

ANNEXURE 5.8 (CHAPTER V , PARA 25) FORM 9 List of Applications for inclusion received in Form 6 Designated location identity (where Constituency (Assembly/£Parliamentary): Tivim Revision identity applications have been received) 1. List number@ 2. Period of applications (covered in this list) From date To date 24/10/2020 24/10/2020 3. Place of hearing * Serial number$ Date of receipt Name of claimant Name of Place of residence Date of Time of of application Father/Mother/ hearing* hearing* Husband and (Relationship)# 1 24/10/2020 Surekha Shirodkar Krishna Shirodkar (H) -, Karkayachoval,, Revora, , £ In case of Union territories having no Legislative Assembly and the State of Jammu and Kashmir Date of exhibition at @ For this revision for this designated location designated location under Date of exhibition at Electoral * Place, time and date of hearings as fixed by electoral registration officer rule 15(b) Registration Officer’s Office under $ Running serial number is to be maintained for each revision for each designated rule 16(b) location # Give relationship as F-Father, M=Mother, and H=Husband within brackets i.e. (F), (M), (H) 07/12/2020 ANNEXURE 5.8 (CHAPTER V , PARA 25) FORM 9 List of Applications for inclusion received in Form 6 Designated location identity (where Constituency (Assembly/£Parliamentary): Tivim Revision identity applications have been received) 1. List number@ 2. Period of applications (covered in this list) From date To date 26/10/2020 26/10/2020 3. Place of hearing * Serial number$ Date of receipt Name of claimant Name of Place of residence Date of Time of of application Father/Mother/ hearing* hearing* Husband and (Relationship)# 1 26/10/2020 Sarvesh Sawant Govind Sawant (F) 229, Near .Govt.