Tribute to Winstonbest Bajan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Darcus Howe: a Political Biography

Bunce, Robin, and Paul Field. "Authors' Preface." Darcus Howe: A Political Biography. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2014. viii–x. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 29 Sep. 2021. <>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 29 September 2021, 20:11 UTC. Copyright © Robin Bunce and Paul Field 2014. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. Authors ’ Preface Writing this book has involved many wonderful experiences. Hours in archives are, of course, the historian ’ s delight, and we thank the staff at the National Archives, the Institute of Race Relations, the George Padmore Institute, the British Library, the Colindale Newspaper Archive, Warwick University Library, Cambridge University Library, the Butler Library at the Columbia University and the archives of the Oilfi eld Workers Trade Union of Trinidad and Tobago, to name but a few. We have spent many hours being entertained by our interviewees. Early on in the project, we had the good fortune to spend an aft ernoon with Farrukh Dhondy. ‘ I expect you want me to tell you all the scandal, ’ was his opener. We earnestly assured him that we were writing a serious political piece, adding that we couldn ’ t believe that there would be enough scandal to fi ll a single page. ‘ Th ere ’ s enough to fi ll seven volumes! ’ , he retorted. One of the stranger experiences, only obliquely related to the project, was an Equality and Diversity training session that one of us was compelled to attend in the summer of 2011. -

Decolonising Knowledge

DECOLONISING KNOWLEDGE Expand the Black Experience in Britain’s heritage “Drawing on his personal web site Chronicleworld.org and digital and print collection, the author challenges the nation’s information guardians to “detoxify” their knowledge portals” Thomas L Blair Commentaries on the Chronicleworld.org Users value the Thomas L Blair digital collection for its support of “below the radar” unreported communities. Here is what they have to say: Social scientists and researchers at professional associations, such as SOSIG and the UK Intute Science, Engineering and Technology, applaud the Chronicleworld.org web site’s “essays, articles and information about the black urban experience that invite interaction”. Black History Month archived Bernie Grant, Militant Parliamentarian (1944-2000) from the Chronicleworld.org Online journalists at the New York Times on the Web nominate THE CHRONICLE: www.chronicleworld.org as “A biting, well-written zine about black life in Britain” and a useful reference in the Arts, Music and Popular Culture, Technology and Knowledge Networks. Enquirers to UK Directory at ukdirectory.co.uk value the Chronicleworld.org under the headings Race Relations Organisations promoting racial equality, anti- racism and multiculturalism. Library”Govt & Society”Policies & Issues”Race Relations The 100 Great Black Britons www.100greatblackbritons.com cites “Chronicle World - Changing Black Britain as a major resource Magazine addressing the concerns of Black Britons includes a newsgroup and articles on topical events as well as careers, business and the arts. www.chronicleworld.org” Editors at the British TV Channel 4 - Black and Asian History Map call the www.chronicleworld.org “a comprehensive site full of information on the black British presence plus news, current affairs and a rich archive of material”. -

This Issue Is Dedicated to the Memory of John La Rose, Founder of New Beacon Books

EnterText 6.3 Dedication and Introduction This issue is dedicated to the memory of John La Rose, founder of New Beacon Books, London. He lived to see the fortieth anniversary, in 2006, of the publishing house—or maisonette, as he sometimes called it, wryly—bookshop and cultural centre he had established. Having come to London from Trinidad in the early 1960s, he always had the intention to start a bookshop in the British capital because he understood how important ideas are if we are to act on our dreams of changing the world. And it was this phrase, so often on his lips, which Horace Ove chose as the title for his feature film about John La Rose’s life, Dream to Change the World (2005). In the intervening decades since its foundation, New Beacon’s impact on the cultural map of Britain, the Caribbean and the wider world has acquired real significance, not least as a bright beacon of what a few individuals can achieve with intelligence, passion and dedication (not money, which nowadays tends to be seen as the only prerequisite). New Beacon was named after the Beacon political movement of 1930s Trinidad, which was associated with the slogan “Agitate! Educate! Federate!” While these words have a particular resonance in Trinidad, of course, they also echo round the wider Anglophone Caribbean, where the West Indies Federation, which had promised a realisation of the dreams of John’s generation, lasted so few years, from 1958 to 1962. And they remain resonant on the global stage, reminding us, as they do, of the need to Paula Burnett: Dedication and Introduction 3 EnterText 6.3 rouse ordinary people’s awareness and feelings, to deepen dialogue and understanding, and to co-operate with one another if our puny individualities are to be able to exert real influence. -

Provisional Report African Union-Caribbean Diaspora Conference, the Brit Oval, London 23-25 April 2007

PROVISIONAL REPORT AFRICAN UNION-CARIBBEAN DIASPORA CONFERENCE, THE BRIT OVAL, LONDON 23-25 APRIL 2007 Annex A: Conference Programme: Annex B: Opening Address of Minister Nkosazana Dlamini- Zuma, Minister of Foreign Affairs for the Republic of South Africa Annex C: Opening Address of Minister Anthony Hylton, Minister of Foreign Affairs of Jamaica. 1. Introduction: On the 23-25 of April 2007 a landmark African-Caribbean conference was held at the Brit Oval in London. (Annex A). The conference was held over two days and included key note addresses from the South African Foreign Minister Dr Nkosazana- Dlamini- Zuma MP (Annex B) and the Jamaican Foreign Minister Mr Anthony Hylton MP (Annex C). Further speakers included academic personalities from the two regions and some based in the UK. Delegates included representatives from the Diaspora groupings for African/Caribbean Groups in the UK and Europe and representatives of academic institutions from leading centres of African/Caribbean Studies in the United Kingdom and experts on Africa and the Caribbean Diaspora in general. 2. Background: On the 17th of March 2005 the South African Minister of Foreign Affairs, Dr Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma, briefed a South Africa-Africa Union- Caribbean Diaspora Conference in Kingston, Jamaica. At the Conference she stressed the commonalities between Africa and the Caribbean based on the fact that “we have come together to affirm our identity as one people, because of our common origins. With Africa not only as our place of common origins, but also widely regarded as the Cradle of Humankind, today we can all say with conviction that African blood flows through our veins.” That Conference in Jamaica was part of the continuous dialogue that is an imperative between the two regions, and should extend to the rest of the African Diaspora and as part of the broader South-South dialogue. -

University of Warwick Institutional Repository

University of Warwick institutional repository: http://go.warwick.ac.uk/wrap A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of Warwick http://go.warwick.ac.uk/wrap/36101 This thesis is made available online and is protected by original copyright. Please scroll down to view the document itself. Please refer to the repository record for this item for information to help you to cite it. Our policy information is available from the repository home page. PARENTAL PARTICIPATION IN PRIMARY EDUCATION. Carol. Vincent. A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Centre for Research in Ethnic Relations University of Warwick. April 1993. -1 Table of Contents Acknowledgements List of abbreviations Summary CHAPTER ONE Parents, Power and Participation: Some Themes 1 The nature of the state education system 2 Power and participation 5 Theorising 'the community' 13 Social democratic ideals: community education 17 Conclusion 23 CHAPTER TWO The Role of 'The Parent' in State Education ' 27 Social democracy and the state education system 27 The rise of the New Right 34 The New Right's education project - the parent as consumer 37 Conclusion 44 CHAPTER THREE Parent Participation in Primary Education: The Present Day 48 Problematizing home-school relationships 48 Parental roles 55 - The supporter-learner model 55 - Parents as consumers: The Parents' Charter 63 - Independent parents 65 - Parents as participants 66 Conclusion 68 CHAPTER FOUR Researching Home-School Relations 71 Case study research - a brief discussion 71 The design of -

Darcus Howe: a Political Biography

Bunce, Robin, and Paul Field. "‘Dabbling with Revolution’: Black Power Comes to Britain." Darcus Howe: A Political Biography. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2014. 27–42. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 1 Oct. 2021. <http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781472544407.ch-002>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 1 October 2021, 10:59 UTC. Copyright © Robin Bunce and Paul Field 2014. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 2 ‘ Dabbling with Revolution ’ : Black Power Comes to Britain Th e Dialectics of Liberation conference of July 1967 brought the 1960s ’ counterculture to the heart of London. Th e 2-week conference, convened by R. D. Laing and leading fi gures in the anti-psychiatry movement, featured contributions from Beat Generation writers William Burroughs and Allen Ginsberg; Emmett Grogan, founder of the San Francisco anarchist movement Th e Diggers; and the Frankfurt School neo-Marxist, Herbert Marcuse (Cooper 1968: 9). Th e conference practised the countercultural values that it preached, spontaneously transforming the Roundhouse and Camden ’ s pubs and bars into informal collegiums, the founding event of the anti-university of London (Ibid., 11). Black Power, a movement that had emerged at the cutting edge of the American Civil Rights struggle the year before, had several representatives at the conference. Th e headline black radical and the most controversial speaker by far was Howe ’ s fellow Trinidadian and childhood friend, Stokely Carmichael, now the harbinger of the Black Power revolution. Th e British press responded to his visit by branding him ‘ an evil campaigner of hate ’ and ‘ the most eff ective preacher of racial hatred at large today ’ (Humphry and Tindall 1977: 63). -

Black Mixed-Race Male Experiences of the UK Secondary School Curriculum

The University of Manchester Research Black mixed-race male experiences of the UK secondary school curriculum DOI: 10.7709/jnegroeducation.86.4.0449 Document Version Accepted author manuscript Link to publication record in Manchester Research Explorer Citation for published version (APA): Joseph-Salisbury, R. (2017). Black mixed-race male experiences of the UK secondary school curriculum. Journal of Negro Education. https://doi.org/10.7709/jnegroeducation.86.4.0449 Published in: Journal of Negro Education Citing this paper Please note that where the full-text provided on Manchester Research Explorer is the Author Accepted Manuscript or Proof version this may differ from the final Published version. If citing, it is advised that you check and use the publisher's definitive version. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the Research Explorer are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Takedown policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please refer to the University of Manchester’s Takedown Procedures [http://man.ac.uk/04Y6Bo] or contact [email protected] providing relevant details, so we can investigate your claim. Download date:29. Sep. 2021 1 Black Mixed-race Male Experiences of the UK Secondary School Curriculum Remi Joseph-Salisbury Leeds Beckett University Drawing on findings from 20 semi-structured interviews carried out in 2013, this article seeks to contribute to the limited body of literature exploring the schooling experiences of the mixed-race population in the United Kingdom. -

The Street Weapons Commission Report

The Street Weapons Commission Report Weapons Commission The Street The Street Weapons Commission Report The impact of knife and gun crime on independent research. They visited The Street Weapons Commission victims, families and whole communities projects which are trying to help our was chaired by Cherie Booth QC, and is devastating. Following a series of most vulnerable young people. its members were Liam Black, social fatal stabbings and shootings in major entrepreneur and former Director of cities across the UK in early 2008 The Street Weapons Commission the Fifteen Foundation, Lord Geoffrey Channel 4 established the Street report is the culmination of their Dear, a distinguished former Chief Weapons Commission – with the investigation. It represents a call to Constable, Professor Gus John, a task of finding out the truth about gun action for our government, our police fellow of the Institute of Education, The Street and knife violence on our streets. forces, local councils, our schools and Mark Johnson, an ex-offender who hospitals and our communities. The is now a special adviser to both the The Commission visited five cities, ages of both victims and perpetrators National Probation Service and the which suffer from some of the worst of weaponised street violence are Prince’s Trust, Ian Levy, founder of Weapons levels of gun and knife attacks: Liverpool, getting younger and the number of The Robert Levy Foundation which London, Birmingham, Glasgow and children and young people carrying was set up following the fatal Manchester. They heard evidence knives is increasing. If this problem stabbing of his son, Fay Selvan, Commission from the local people most affected, is not tackled head on – now – then Chief Executive of The Big Life Group police officers, politicians, local the implications are serious for our and Howard Williamson who is authorities, community groups and future individual safety, community Professor of European Youth Policy campaigners. -

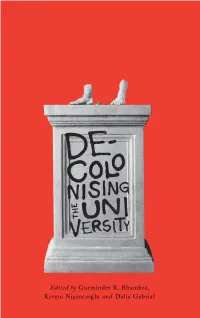

Decolonising the University

Decolonising the University Decolonising the University Edited by Gurminder K. Bhambra, Dalia Gebrial and Kerem Nişancıoğlu First published 2018 by Pluto Press 345 Archway Road, London N6 5AA www.plutobooks.com Copyright © Gurminder K. Bhambra, Dalia Gebrial and Kerem Nişancıoğlu 2018 The right of the individual contributors to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978 0 7453 3821 7 Hardback ISBN 978 0 7453 3820 0 Paperback ISBN 978 1 7868 0315 3 PDF eBook ISBN 978 1 7868 0317 7 Kindle eBook ISBN 978 1 7868 0316 0 EPUB eBook This book is printed on paper suitable for recycling and made from fully managed and sustained forest sources. Logging, pulping and manufacturing processes are expected to conform to the environmental standards of the country of origin. Typeset by Stanford DTP Services, Northampton, England Simultaneously printed in the United Kingdom and United States of America Bhambra.indd 4 29/08/2018 17:13 Contents 1 Introduction: Decolonising the University? 1 Gurminder K. Bhambra, Dalia Gebrial and Kerem Nişancıoğlu PART I CONTEXTS: HISTORICAL AND DISCPLINARY 2 Rhodes Must Fall: Oxford and Movements for Change 19 Dalia Gebrial 3 Race and the Neoliberal University: Lessons from the Public University 37 John Holmwood 4 Black/Academia 53 Robbie Shilliam 5 Decolonising Philosophy 64 Nelson Maldonado-Torres, Rafael Vizcaíno, Jasmine Wallace and Jeong Eun Annabel We PART II INSTITUTIONAL INITIATIVES 6 Asylum University: Re-situating Knowledge-exchange along Cross-border Positionalities 93 Kolar Aparna and Olivier Kramsch 7 Diversity or Decolonisation? Researching Diversity at the University of Amsterdam 108 Rosalba Icaza and Rolando Vázquez 8 The Challenge for Black Studies in the Neoliberal University 129 Kehinde Andrews 9 Open Initiatives for Decolonising the Curriculum 145 Pat Lockley vi . -

Black Community Self-Narration, and Black Power for Children in the US and UK

Research on Diversity in Youth Literature Volume 3 Issue 1 Minstrelsy and Racist Appropriation Article 7 (3.1) and General Issue (3.2) April 2021 Power Primers: Black Community Self-Narration, and Black Power for Children in the US and UK Karen Sands-O'Connor Newcastle University Follow this and additional works at: https://sophia.stkate.edu/rdyl Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons, and the Literature in English, North America, Ethnic and Cultural Minority Commons Recommended Citation Sands-O'Connor, Karen (2021) "Power Primers: Black Community Self-Narration, and Black Power for Children in the US and UK," Research on Diversity in Youth Literature: Vol. 3 : Iss. 1 , Article 7. Available at: https://sophia.stkate.edu/rdyl/vol3/iss1/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by SOPHIA. It has been accepted for inclusion in Research on Diversity in Youth Literature by an authorized editor of SOPHIA. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Sands-O'Connor: Power Primers: Black Community Self-Narration, and Black Power fo “We want education that teaches us our true history and our role in the present-day society. We believe in an educational system that will give to our people a knowledge of the self. If you do not have knowledge of yourself and your position in the society and in the world, then you will have little chance to know anything else” (Huey Newton and Bobby Seale, point 5). In 1966, Huey Newton and Bobby Seale created a ten-point program for their nascent Black Panther Party organization based in Oakland, California. -

James Kelman's Interview with John La Rose

The full interview with John La Rose1 More than twenty five years ago I was asked to interview John La Rose for the arts and culture journal Variant 19. Malcolm Dickson was then editor. The interview took place in John’s house in Finsbury Park. Malcolm organized the recording apparatus and also jumped about taking photographs. I had known John for a few years by then and had been in his company quite often; my only plan, therefore, was to start talking. He was a very strong and experienced orator, and with a tremendous breadth of knowledge. He was used to the toughest forms of meetings, those that began in confrontation and moved towards negotiation. I knew he would go where he thought necessary and return near enough to the starting point: my job was to resist interfering. The general population are unaware of the depth and complexity of the struggle of black people and other minorities in the United Kingdom. This transcription of a talk by John La Rose allows an insight into that and of the richness of the Caribbean side of its social and intellectual tradition. Insight here is gained into the inseparable nature of the culture and the political. There is also the matter of John's own centrality to some of the more crucial political interventions in his time. It should be a matter of concern how easily such a figure can be airbrushed from the political and cultural history of the UK, and the fundamental role played by John La Rose, his peers and contemporaries. -

Althea Mcnish Wednesday 22 April 2020

Special and Reflective Tribute to Althea McNish Wednesday 22 April 2020 Welcome to our Special and Reflective Tribute to Althea McNish, as we share our heritage from Bruce Castle Museum & Archive. Our originally-planned post from the weekend has been brought forward in honour of Althea McNish, the internationally-important textile designer and artist who was one of our neighbours - living here in Haringey, in West Green Road in Tottenham for over 50 years. It was announced on Tuesday in the Trinidad and Tobago Newsday that she very sadly passed away last week at the age of 95. Our current exhibition at Bruce Castle - We Made It! - has a dedicated area for Althea’s work from our collections. Many will recall we had a very special event last October during Black History Month led by Rose Sinclair, Lecturer in Design (Textiles) at Goldsmith’s (University of London), celebrating Althea’s life and work, her involvement in establishing the Caribbean Artists’ Movement and John La Rose, as well as the prestigious commissions for Liberty, Dior, Jacguar, Heal’s and Conran. Needless to say, her art was also the inspiration for a workshop we had planned for young people and families during Women’s History Month back in March, which only could not go ahead because of the lock-down. Rose Sinclair here very kindly shares her own personal tribute, in honour of Althea: Althea McNish-Weiss On 31st October 2019, Bruce Castle Museum held a celebration to close Black History Month. This event was to honour those in the community who in particular were inspiring to the next generation of emerging talent - but were equally an inspiration to us all.