Oral History Interview #394 Fred “Fritz” Stanley Bertsch, Jr. Uss Case

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

United States Navy and World War I: 1914–1922

Cover: During World War I, convoys carried almost two million men to Europe. In this 1920 oil painting “A Fast Convoy” by Burnell Poole, the destroyer USS Allen (DD-66) is shown escorting USS Leviathan (SP-1326). Throughout the course of the war, Leviathan transported more than 98,000 troops. Naval History and Heritage Command 1 United States Navy and World War I: 1914–1922 Frank A. Blazich Jr., PhD Naval History and Heritage Command Introduction This document is intended to provide readers with a chronological progression of the activities of the United States Navy and its involvement with World War I as an outside observer, active participant, and victor engaged in the war’s lingering effects in the postwar period. The document is not a comprehensive timeline of every action, policy decision, or ship movement. What is provided is a glimpse into how the 20th century’s first global conflict influenced the Navy and its evolution throughout the conflict and the immediate aftermath. The source base is predominately composed of the published records of the Navy and the primary materials gathered under the supervision of Captain Dudley Knox in the Historical Section in the Office of Naval Records and Library. A thorough chronology remains to be written on the Navy’s actions in regard to World War I. The nationality of all vessels, unless otherwise listed, is the United States. All errors and omissions are solely those of the author. Table of Contents 1914..................................................................................................................................................1 -

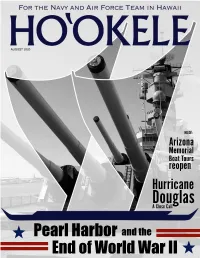

Douglas Close Call

AUGUST 2020 INSIDE: Arizona Memorial Boat Tours reopen Hurricane ADouglas Close Call Pearl Harbor and the End of World War II HAWAII PHOTO OF THE MONTH Your Navy Team in Hawaii CONTENTS Commander, Navy Region Hawaii oversees two installations: Joint Base Pearl Harbor-Hickam on PREPAREDNESS Oahu and Pacific Missile Range Facility, Barking Sands, on Kauai. As Naval Surface Group Middle A Close Call Director of Public Aff airs, Navy Region Hawaii Pacific, we provide oversight for the ten surface Highlights of Hurricane Lydia Robertson ships homeported at JBPHH. Navy aircraft Douglas squadrons are also co-located at Marine Corps Deputy Director of Public Aff airs, Base Hawaii, Kaneohe, Oahu, and training is Navy Region Hawaii sometimes also conducted on other islands, but Mike Andrews most Navy assets are located at JBPHH and PMRF. These two installations serve fleet, fighter │4-5 Director of Public Aff airs, and family under the direction of Commander, Navy Joint Base Pearl Harbor-Hickam Installations Command. ENVIRONMENTAL Chuck Anthony A guided-missile cruiser and destroyers of MDSU-1, NAVSEA Director of Public Aff airs, Commander, Naval Surface Force Pacific deploy remove FORACS Commander, Navy Region Pacifi c Missile Range Facility equipment off Nanakuli Tom Clements independently or as part of a group for Commander, Hawaii And Naval Surface Group U.S. Third Fleet and in the Seventh Fleet and Fifth Middle Pacifi c Managing Editor Fleet areas of responsibility. The Navy, including Anna Marie General your Navy team in Hawaii, builds partnerships and REAR ADM. ROBERT CHADWICK strengthens interoperability in the Pacific. Each │6-7 Military Editor year, Navy ships, submarines and aircraft from MC2 Charles Oki Hawaii participate in various training exercises with COVER STORY allies and friends in the Pacific and Indian Oceans to Contributing Staff strengthen interoperability. -

US Fleet Organization, 1939

US Fleet Organization 1939 Battle Force US Fleet: USS California (BB-44)(Force Flagship) Battleships, Battle Force (San Pedro) USS West Virginia (BB-48)(flagship) Battleship Division 1: USS Arizona (BB-39)(flag) USS Nevada (BB-36) USS Pennsylvania (BB-38)(Fl. Flag) Air Unit - Observation Sqn 1-9 VOS Battleship Division 2: USS Tennessee (BB-43)(flag) USS Oklahoma (BB-37) USS California (BB-44)(Force flagship) Air Unit - Observation Sqn 2-9 VOS Battleship Division 3: USS Idaho (BB-42)(flag) USS Mississippi (BB-41) USS New Mexico (BB-40) Air Unit - Observation Sqn 3-9 VOS Battleship Division 4: USS West Virginia (BB-48)(flag) USS Colorado (BB-45) USS Maryland (BB-46) Air Unit - Observation Sqn 4-9 VOS Cruisers, Battle Force: (San Diego) USS Honolulu (CL-48)(flagship) Cruiser Division 2: USS Trenton (CL-11)(flag) USS Memphis (CL-13) Air Unit - Cruiser Squadron 2-4 VSO Cruiser Division 3: USS Detroit (CL-8)(flag) USS Cincinnati (CL-6) USS Milwaukee (CL-5) Air Unit - Cruiser Squadron 3-6 VSO Cruise Division 8: USS Philadelphia (CL-41)(flag) USS Brooklyn (CL-40) USS Savannah (CL-42) USS Nashville (CL-43) Air Unit - Cruiser Squadron 8-16 VSO Cruiser Division 9: USS Honolulu (CL-48)(flag) USS Phoneix (CL-46) USS Boise (CL-47) USS St. Louis (CL-49)(when commissioned Air Unit - Cruiser Squadron 8-16 VSO 1 Destroyers, Battle Force (San Diego) USS Concord (CL-10) Ship Air Unit 2 VSO Destroyer Flotilla 1: USS Raleigh (CL-7)(flag) Ship Air Unit 2 VSO USS Dobbin (AD-3)(destroyer tender) (served 1st & 3rd Squadrons) USS Whitney (AD-4)(destroyer tender) -

US COLD WAR AIRCRAFT CARRIERS Forrestal, Kitty Hawk and Enterprise Classes

US COLD WAR AIRCRAFT CARRIERS Forrestal, Kitty Hawk and Enterprise Classes BRAD ELWARD ILLUSTRATED BY PAUL WRIGHT © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com NEW VANGUARD 211 US COLD WAR AIRCRAFT CARRIERS Forrestal, Kitty Hawk and Enterprise Classes BRAD ELWARD ILLUSTRATED BY PAUL WRIGHT © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 4 ORIGINS OF THE CARRIER AND THE SUPERCARRIER 5 t World War II Carriers t Post-World War II Carrier Developments t United States (CVA-58) THE FORRESTAL CLASS 11 FORRESTAL AS BUILT 14 t Carrier Structures t The Flight Deck and Hangar Bay t Launch and Recovery Operations t Stores t Defensive Systems t Electronic Systems and Radar t Propulsion THE FORRESTAL CARRIERS 20 t USS Forrestal (CVA-59) t USS Saratoga (CVA-60) t USS Ranger (CVA-61) t USS Independence (CVA-62) THE KITTY HAWK CLASS 26 t Major Differences from the Forrestal Class t Defensive Armament t Dimensions and Displacement t Propulsion t Electronics and Radars t USS America, CVA-66 – Improved Kitty Hawk t USS John F. Kennedy, CVA-67 – A Singular Class THE KITTY HAWK AND JOHN F. KENNEDY CARRIERS 34 t USS Kitty Hawk (CVA-63) t USS Constellation (CVA-64) t USS America (CVA-66) t USS John F. Kennedy (CVA-67) THE ENTERPRISE CLASS 40 t Propulsion t Stores t Flight Deck and Island t Defensive Armament t USS Enterprise (CVAN-65) BIBLIOGRAPHY 47 INDEX 48 © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com US COLD WAR AIRCRAFT CARRIERS FORRESTAL, KITTY HAWK AND ENTERPRISE CLASSES INTRODUCTION The Forrestal-class aircraft carriers were the world’s first true supercarriers and served in the United States Navy for the majority of America’s Cold War with the Soviet Union. -

SAN DIEGO SHIP MODELERS GUILD Ship’S Name: USS CHESTER (CA 27) Model Builder: Frank Dengler 19 October 20 1

SAN DIEGO SHIP MODELERS GUILD Ship’s Name: USS CHESTER (CA 27) Model Builder: Frank Dengler 19 October 20 1. Ship’s History a. Type/Class: Heavy Cruiser / NORTHAMPTON (CA 26) Originally classified as light cruisers (CL) based on armor and displacement, the class was reclassified as heavy cruisers (CA) 1 July 1931 based on 8”/55 main batteries. Raised foc’sles in NORTHAMPTON, CHESTER, and LOUISVILLE (CA 28) ended just aft of the forward superstructure. Raised foc’sles in CHICAGO (CA 29), HOUSTON (CA 30), and AUGUSTA (CA 31) extended aft of the forward stack for flag staff berthing. b. Namesake: City of Chester, PA. Model builder Frank Dengler was raised in Devon, Chester County, PA. c. Shipbuilder & Location: New York Shipbuilding, Camden, NJ d. Date Commissioned: 24 June 1930. CHESTER was launched 3 July 1929, Frank Dengler’s father’s 18th birthday. e. Characteristics Upon Commissioning: Displacement 9,300 tons, Length: 600' 3", Beam: 66' 1", Draft: 16’ 4” to 23', Armament 9 x 8"/55 in 3 x turrets, 4 x 5"/25 gun mounts, 8 x M2 .50” (12.7mm) machineguns (MGs), 6 x 21" torpedo tubes, 4 Aircraft, Armor: 3 3/4" Belt, 2 ½” Turrets,1" Deck, 1 ¼” Conning Tower, Propulsion: 8 x White-Forster boilers, 4 x Parsons steam turbines, 4 screws, 107,000 SHP; Speed: 32.7 kts, Range 10,000 nm, Compliment: 574 (later 95 officers, 608 enlisted). Figure 1 - CHESTER in July 1931 in “as built” configuration. Note hanger around aft stack, trainable aircraft catapults port & starboard, & aircraft recovery crane amidships, extensive boat compliment and boat crane aft. -

THE JERSEYMAN 5 Years - Nr

N J B B June 4, 2007 Midway Atoll photo courtesy of 4th Quarter Welford Sims, Raleigh, North Carolina 2007 "Rest well, yet sleep lightly and hear the call, if again sounded, to provide firepower for freedom…” THE JERSEYMAN 5 Years - Nr. 56 The Battle of Midway — 65 years... MIDWAY ATOLL (June 4, 2007) - Commander, U.S. Pacific Fleet, Adm. Robert F. Willard, delivers his remarks during the 65th anniversary of the Battle of Midway commemoration ceremony on Midway Atoll. (U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist 1st Class James E. Foehl) 2 The Jerseyman Battle of Midway Commemoration... MIDWAY ATOLL – Distinguished visitors and more than 1,500 guests of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, International Midway Memorial Foundation and the U.S. Pacific Fleet, assembled on Midway Atoll, June 4, to commemorate the 65th anni- versary of the Battle of Midway. “We‟re gathered here today at one of the most re- mote and special places on earth. Midway, is where the course of history was changed,” said the Honorable Linda Lingle, Governor of Hawaii. The Battle of Midway was fought June 4 – 7, 1942, and served as a turning point in the Pacific during World War II. “No one knew it at the time, but the tide of war in the Pacific had turned because of the heroism and sheer determination of those who fought on June 4, 1942,” said Dr. James M. D’Angelo, president and chairman, International Midway Memorial Foundation. “It‟s not hard to imagine what we would‟ve heard if we‟d have been here this day 65 years ago. -

The USS Arizona Memorial

National Park Service Teaching with Historic Places U.S. Department of the Interior Remembering Pearl Harbor: The USS Arizona Memorial Remembering Pearl Harbor: The USS Arizona Memorial (National Park Service Photo by Jayme Pastoric) Today the battle-scarred, submerged remains of the battleship USS Arizona rest on the silt of Pearl Harbor, just as they settled on December 7, 1941. The ship was one of many casualties from the deadly attack by the Japanese on a quiet Sunday that President Franklin Roosevelt called "a date which will live in infamy." The Arizona's burning bridge and listing mast and superstructure were photographed in the aftermath of the Japanese attack, and news of her sinking was emblazoned on the front page of newspapers across the land. The photograph symbolized the destruction of the United States Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor and the start of a war that was to take many thousands of American lives. Indelibly impressed into the national memory, the image could be recalled by most Americans when they heard the battle cry, "Remember Pearl Harbor." More than a million people visit the USS Arizona Memorial each year. They file quietly through the building and toss flower wreaths and leis into the water. They watch the iridescent slick of oil that still leaks, a drop at a time, from ruptured bunkers after more than 50 years at the bottom of the sea, and they read the names of the dead carved in marble on the Memorial's walls. National Park Service Teaching with Historic Places U.S. Department of the Interior Remembering Pearl Harbor: The USS Arizona Memorial Document Contents National Curriculum Standards About This Lesson Getting Started: Inquiry Question Setting the Stage: Historical Context Locating the Site: Map 1. -

The Weeping Monument: a Pre and Post Depositional Site

THE WEEPING MONUMENT: A PRE AND POST DEPOSITIONAL SITE FORMATION STUDY OF THE USS ARIZONA by Valerie Rissel April, 2012 Director of Thesis: Dr. Brad Rodgers Major Department: Program in Maritime History and Archaeology Since its loss on December 7, 1941, the USS Arizona has been slowly leaking over 9 liters of oil per day. This issue has brought about conversations regarding the stability of the wreck, and the possibility of defueling the 500,000 to 600,000 gallons that are likely residing within the wreck. Because of the importance of the wreck site, a decision either way is one which should be carefully researched before any significant changes occur. This research would have to include not only the ship and its deterioration, but also the oil’s effects on the environment. This thesis combines the historical and current data regarding the USS Arizona with case studies of similar situations so a clearer picture of the future of the ship can be obtained. THE WEEPING MONUMENT: A PRE AND POST DEPOSITIONAL SITE FORMATION STUDY OF THE USS ARIZONA Photo courtesy of Battleship Arizona by Paul Stillwell A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Program in Maritime Studies Department of History East Carolina University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Masters in Maritime History and Archaeology by Valerie Rissel April, 2012 © Valerie Rissel, 2012 THE WEEPING MONUMENT: A PRE AND POST DEPOSITIONAL SITE FORMATION STUDY OF THE USS ARIZONA by Valerie Rissel APPROVED BY: DIRECTOR OF THESIS______________________________________________________________________ Bradley Rodgers, Ph.D. COMMITTEE MEMBER________________________________________________________ Michael Palmer, Ph.D. -

Pearl Harbor

INSIDE Hawaii Military Week Events A-2 Word on the Street A-3 Radio Recon Screening A-4 SACO of the Quarter A-6 Every Clime and Place A-8 Asian/Pacific Heritage B-1 MCCS B-2 Sports B-3 Windward Half Marathon B-4 M ARINEARINEMarine Makeponos B-5 VolumeM 30, Number 19 www.mcbh.usmc.mil May 24, 2001 Epic premiers on Oahu Camp Smith Marine honored Cpl. Jacques-René Hébert MarForPac Public Affairs CAMP H.M. SMITH – A product from a diverse past, his parents had crossed archaic and outdated social and cultural lines to make a life together. His father was full-blooded Jewish, while his mother was half Spanish and half Puerto Rican. The two met in his father’s native Brooklyn, N.Y and eventually settled there. A city of asphalt and anger, poetry and police, Brooklyn boasts a patchwork of neighborhoods that vary drastically in nationality and cultural identities. But for 1st Sgt. Harry Rivera of Headquarters and Service Co., Camp H.M. Smith, his upbringing was filled with love and discipline, which shel- tered him from the hard New York streets. “New York’s diversity gave me an op- portunity to see from many different perspectives,” Rivera reflected. “My father was firm,” he remem- bered. “Whatever I did, he stressed that I do it to the best of my ability.” Image by Andrew Cooper for Touchstone Pictures And this he did. Rivera was recog- A stupendous air attack upon Pearl Harbor by bombers from the Imperial Empire of Japan shatters the world and changes the nized as Marine Corps Times “Marine course of history, in Touchstone Pictures’ epic drama, “Pearl Harbor,” which opens in theaters Friday. -

302.Gyorsárverés Képeslapok

Gyorsárverés 302. képeslapok Az árverés anyaga megtekinthető weboldalunkon és irodánkban (VI. Andrássy út 16. III. emelet. Nyitva tartás: H-Sz: 10-17, Cs: 10-19 óráig, P: Zárva) július 17-20-ig. AJÁNLATTÉTELI HATÁRIDŐ: 2017. július 20. 19 óra. Ajánlatokat elfogadunk írásban, személyesen, vagy postai úton, telefonon a 317-4757, 266-4154 számokon, faxon a 318-4035 számon, e-mailben az [email protected], illetve honlapunkon (darabanth.com), ahol online ajánlatot tehet. ÍRÁSBELI (fax, email) ÉS TELEFONOS AJÁNLATOKAT 18:30-IG VÁRUNK. A megvásárolt tételek átvehetők 2017. július 24-én 10 órától. Utólagos eladás július 21-27-ig. (Nyitvatartási időn kívül honlapunkon vásárolhat a megmaradt tételekből.) Anyagbeadási határidő a 303. gyorsárverésre: július 19. Az árverés FILATÉLIA, NUMIZMATIKA, KÉPESLAP és az EGYÉB GYŰJTÉSI TERÜLETEK tételei külön katalógusokban szerepelnek! A vásárlói jutalék 22% Részletes árverési szabályzat weboldalunkon és irodánkban megtekinthető. darabanth.com Tisztelt Ügyfelünk! Nyáron érdemes eladni! Amíg Ön pihen, mi dolgozunk. Csak nálunk vannak folyamatos aukciók nyáron is. Adja be most tételeit és profitáljon a kiemelt figyelemből! 302. aukció: Megtekintés: július 17-20-ig! Tételek átvétele július 24-én 10 órától! 301. aukció elszámolás július 25-tól! Amennyiben átutalással kéri az elszámolását, kérjük jelezze e-mailben, vagy telefonon. Kérjük az elszámoláshoz a tétel átvételi listát szíveskedjenek elhozni! Kezelési költség 240 ft / tétel / árverés. A 2. indításnál 120 ft A vásárlói jutalék 22% Jelmagyarázat: Használatlan Megíratlan lap bélyegzéssel, vagy megírt lap bélyeg nélkül Postázott képeslap (small tear): Kis szakadás(Rb): Hátoldalt sérült (EM): Sarokhiány (EK): Apró saroktörés (EB): Saroktörés (fl): Foltos (fa): Törött (b): Sérült Emb: Dombor T1: Kifogástalan T2: Jó T3: Kis hibával T4: Hibás lap Ga: Díjjegyes So. -

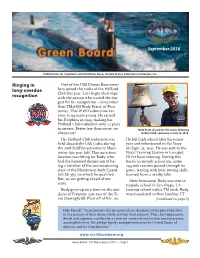

Ringing in Long-Overdue Recognition

September 2018 Publication for members of USS Illinois Base, United States Submarine Veterans, Inc. Ringing in One of fi ve USS Illinois Base mem- long-overdue bers joined the ranks of the Holland Club this year. Let’s begin their saga recognition with the person who waited the lon- gest for his recognition – none other than TM3(SS) Rudy Kraut, of Peca- tonica. This WWII submarine vet- eran, is 94-years young. He earned his Dolphins in 1945, making his Holland Club induction only 22 years in arrears. Better late than never, we Rudy Kraut aboard the USS Cobia following always say! Holland Club ceremony on July 13, 2018. His Holland Club induction was He left high school after his junior held aboard the USS Cobia during year and volunteered in the Navy the 2018 SubFest activities in Mani- on Sept. 25, 1943. He was sent to the towoc this past July. This initiation Naval Training Station in Farragut, location was fi tting for Rudy, who ID for basic training. During this had the honored distinction of be- base’s 30-month activation, some ing a member of the commissioning 293,000 recruits passed through its crew of the Manitowoc-built Lizard- gates, leaving with boat rowing skills fi sh SS-373, on which he qualifi ed. learned from a nearby lake. But, we are getting ahead of our After bootcamp, Rudy was sent to story. torpedo school in San Diego, CA. Rudy grew up on a farm on the out- Leaving school with a TM rank, Rudy skirts of Freeport, just east of the Ti- was transferred to New London, CT tan (Springfi eld) Plant off of Rte. -

The Hobson Incident

The Hobson Incident Late on Saturday night, April 26, 1952, U.S.S. Wasp was completing night maneuvers some 1,200 miles east of New York. She turned into the wind to recover her aircraft. The skipper of the USS Hobson, a destroyer-minesweeper, apparently became confused in the dark and made a few turns that ended with the Hobson cutting in front of Wasp. The Wasp cut the Hobson in two. From there, it rapidly got worse. The Hobson was hit aft of midship, and the entire ship sank in four minutes. Her captain and 174 other men were lost. In rolling over, Hobson’s keel sliced off an 80-ton section of Wasp’s bow, from keel to about waterline, the section being carried away, with interior deck levels, oil tanks, fittings, and gears. Those men from the Hobson who were fortunate enough to be thrown clear and rescued were covered with oil from Wasp’s broken tanks. Fortunately, there were no crew quarters located in Wasp’s bow, and Wasp, in fact, suffered no casualties in the affair. Wasp had been under orders to relieve the carrier Tarawa farther east. Her bulkheads holding against the open bow, she turned for repairs at New York. Proceeding at a ten-knot speed, often reduced to near zero when heavy going forced her to proceed stern-first, she almost lost her two anchor chains ($40,000 each). Wasp, drydock-free by May 19, then ammunitioned and service fitted, was back on sea duty in less than five weeks, a record for major ship repairs.