Chapter 4 the Development of New Regulations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

President, Prime Minister, Or Constitutional Monarch?

I McN A I R PAPERS NUMBER THREE PRESIDENT, PRIME MINISTER, OR CONSTITUTIONAL MONARCH? By EUGENE V. ROSTOW THE INSTITUTE FOR NATIONAL S~RATEGIC STUDIES I~j~l~ ~p~ 1~ ~ ~r~J~r~l~j~E~J~p~j~r~lI~1~1~L~J~~~I~I~r~ ~'l ' ~ • ~i~i ~ ,, ~ ~!~ ,,~ i~ ~ ~~ ~~ • ~ I~ ~ ~ ~i! ~H~I~II ~ ~i~ ,~ ~II~b ~ii~!i ~k~ili~Ii• i~i~II~! I ~I~I I• I~ii kl .i-I k~l ~I~ ~iI~~f ~ ~ i~I II ~ ~I ~ii~I~II ~!~•b ~ I~ ~i' iI kri ~! I ~ • r rl If r • ~I • ILL~ ~ r I ~ ~ ~Iirr~11 ¸I~' I • I i I ~ ~ ~,i~i~I•~ ~r~!i~il ~Ip ~! ~ili!~Ii!~ ~i ~I ~iI•• ~ ~ ~i ~I ~•i~,~I~I Ill~EI~ ~ • ~I ~I~ I¸ ~p ~~ ~I~i~ PRESIDENT, PRIME MINISTER, OR CONSTITUTIONAL MONARCH.'? PRESIDENT, PRIME MINISTER, OR CONSTITUTIONAL MONARCH? By EUGENE V. ROSTOW I Introduction N THE MAKING and conduct of foreign policy, ~ Congress and the President have been rivalrous part- ners for two hundred years. It is not hyperbole to call the current round of that relationship a crisis--the most serious constitutional crisis since President Franklin D. Roosevelt tried to pack the Supreme Court in 1937. Roosevelt's court-packing initiative was highly visible and the reaction to it violent and widespread. It came to an abrupt and dramatic end, some said as the result of Divine intervention, when Senator Joseph T. Robinson, the Senate Majority leader, dropped dead on the floor of the Senate while defending the President's bill. -

The Westminster Model, Governance, and Judicial Reform

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Previously Published Works Title The Westminster Model, Governance, and Judicial Reform Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/82h2630k Journal Parliamentary Affairs, 61 Author Bevir, Mark Publication Date 2008 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California THE WESTMINSTER MODEL, GOVERNANCE, AND JUDICIAL REFORM By Mark Bevir Published in: Parliamentary Affairs 61 (2008), 559-577. I. CONTACT INFORMATION Department of Political Science, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720-1950 Email: [email protected] II. BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE Mark Bevir is a Professor in the Department of Political Science, University of California, Berkeley. He is the author of The Logic of the History of Ideas (1999) and New Labour: A Critique (2005), and co-author, with R. A. W. Rhodes, of Interpreting British Governance (2003) and Governance Stories (2006). 1 Abstract How are we to interpret judicial reform under New Labour? What are its implications for democracy? This paper argues that the reforms are part of a broader process of juridification. The Westminster Model, as derived from Dicey, upheld a concept of parliamentary sovereignty that gives a misleading account of the role of the judiciary. Juridification has arisen along with new theories and new worlds of governance that both highlight and intensify the limitations of the Westminster Model so conceived. New Labour’s judicial reforms are attempts to address problems associated with the new governance. Ironically, however, the reforms are themselves constrained by a lingering commitment to an increasingly out-dated Westminster Model. 2 THE WESTMINSTER MODEL, GOVERNANCE, AND JUDICIAL REFORM Immediately following the 1997 general election in Britain, the New Labour government started to pursue a series of radical constitutional reforms with the overt intention of making British political institutions more effective and more accountable. -

Legislative Process Lpbooklet 2016 15Th Edition.Qxp Booklet00-01 12Th Edition 11/18/16 3:00 PM Page 1

LPBkltCvr_2016_15th edition-1.qxp_BkltCvr00-01 12th edition 11/18/16 2:49 PM Page 1 South Carolina’s Legislative Process LPBooklet_2016_15th edition.qxp_Booklet00-01 12th edition 11/18/16 3:00 PM Page 1 THE LEGISLATIVE PROCESS LPBooklet_2016_15th edition.qxp_Booklet00-01 12th edition 11/18/16 3:00 PM Page 2 October 2016 15th Edition LPBooklet_2016_15th edition.qxp_Booklet00-01 12th edition 11/18/16 3:00 PM Page 3 THE LEGISLATIVE PROCESS The contents of this pamphlet consist of South Carolina’s Legislative Process , pub - lished by Charles F. Reid, Clerk of the South Carolina House of Representatives. The material is reproduced with permission. LPBooklet_2016_15th edition.qxp_Booklet00-01 12th edition 11/18/16 3:00 PM Page 4 LPBooklet_2016_15th edition.qxp_Booklet00-01 12th edition 11/18/16 3:00 PM Page 5 South Carolina’s Legislative Process HISTORY o understand the legislative process, it is nec - Tessary to know a few facts about the lawmak - ing body. The South Carolina Legislature consists of two bodies—the Senate and the House of Rep - resentatives. There are 170 members—46 Sena - tors and 124 Representatives representing dis tricts based on population. When these two bodies are referred to collectively, the Senate and House are together called the General Assembly. To be eligible to be a Representative, a person must be at least 21 years old, and Senators must be at least 25 years old. Members of the House serve for two years; Senators serve for four years. The terms of office begin on the Monday following the General Election which is held in even num - bered years on the first Tuesday after the first Monday in November. -

![The Constitution of the United States [PDF]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2214/the-constitution-of-the-united-states-pdf-432214.webp)

The Constitution of the United States [PDF]

THE CONSTITUTION oftheUnitedStates NATIONAL CONSTITUTION CENTER We the People of the United States, in Order to form a within three Years after the fi rst Meeting of the Congress more perfect Union, establish Justice, insure domestic of the United States, and within every subsequent Term of Tranquility, provide for the common defence, promote ten Years, in such Manner as they shall by Law direct. The the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty to Number of Representatives shall not exceed one for every ourselves and our Posterity, do ordain and establish this thirty Thousand, but each State shall have at Least one Constitution for the United States of America. Representative; and until such enumeration shall be made, the State of New Hampshire shall be entitled to chuse three, Massachusetts eight, Rhode-Island and Providence Plantations one, Connecticut fi ve, New-York six, New Jersey four, Pennsylvania eight, Delaware one, Maryland Article.I. six, Virginia ten, North Carolina fi ve, South Carolina fi ve, and Georgia three. SECTION. 1. When vacancies happen in the Representation from any All legislative Powers herein granted shall be vested in a State, the Executive Authority thereof shall issue Writs of Congress of the United States, which shall consist of a Sen- Election to fi ll such Vacancies. ate and House of Representatives. The House of Representatives shall chuse their SECTION. 2. Speaker and other Offi cers; and shall have the sole Power of Impeachment. The House of Representatives shall be composed of Mem- bers chosen every second Year by the People of the several SECTION. -

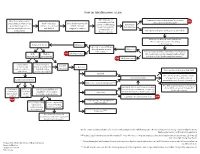

Idea Becomes a Law

How an Idea Becomes a Law Bill is introduced Ideas from many sources: Committee reports “do not pass” or does not STOP and undergoes First constituents, interest groups, Author requests Bill is filed electronically take action on the measure.* and Second Readings. Committee government agencies, bill to be researched with Clerk and is Speaker assigns it to Consideration interim studies, businesses, and drafted. assigned a number. committee(s) or the Governor. Bill reported “do pass” or “do pass as amended.” direct to calendar. Bill moves to General Order. Available to Floor Leader for possible scheduling Returned to House Bill passes on Floor Agenda. Engrossed to Senate: Bill goes through similar process Bill passes in the Senate. ** Floor Consideration: Bill scheduled on Floor Agenda. With Without STOP Bill does not pass Bill is explained, possibly amended, debated, and amendments amendments voted upon. Third Reading and final passage. ** STOP Bill does not pass House refuses House concurs in Enrolled to concur and Senate amendments. To Governor to Governor requests conference Fourth Reading Becomes law on date specified in bill with Senate. and final passage.** Signs bill If no date is specified, and bill contains To Secretary of State emergency clause, bill is effective Conference Committee immediately upon Governor’s signature. Bill becomes law without signature*** If no date is specified, and no emergency Two-thirds vote in each house to override clause, bill becomes law 90 days after Conference CCR filed: CCR electronically filed and veto, unless passed with an emergency, sine die adjournment. Committee Conferees available for Floor Leader Vetoes bill which then requires a three-fourths vote. -

How a Bill Becomes 4

WELCOME TO THE WISCONSIN STATE ASSEMBLY ince becoming a state in 1848, Wisconsin has continued to demonstrate strong leadership and democracy. Because TABLE OF CONTENTS S 2 ...... Introduction of this proud history, our state has been looked to repeatedly as a national leader in government 4 ...... “The Law Needs to Change” innovation and reform. “How A Bill Becomes 4 ...... WisconsinEye Provides View of the Legislature Law” was created to help visitors understand 5 ...... Deliberation and Examination Wisconsin’s legislative process and provide 5 ...... Making a Good Idea Better suggestions on how citizens can participate in 6 ...... The Importance of Caucuses that process. This booklet explains how one idea 7 ...... First & Second Reading or inspiration becomes a bill and moves through 7 ...... Third Reading and Passage the legislative process and into the law books. 7 ...... On to the Senate It is a long road from initial development of an 8 ...... Assembly Bill 27 idea to the emergence of a new law. During 9 ...... Approval of the Governor and Into the Law Books consideration, the bill will be scrutinized and 9 ...... Conclusion examined, criticized and praised. It will be 10 .... Staying in Touch–How to Contact changed, improved, strengthened, and even Your State Representative weakened. If passed, it will undergo the ultimate 11 .... Find Information Online test of merit—time. 12 .... “How a Bill Becomes Law” Cartoon 13 .... “How a Bill Becomes Law” Flow Chart *Words in bold print are defined in the Glossary at the back of the booklet. 14 .... Glossary In this booklet, the bill used as an example of “How a Bill Becomes Law” is 2015 Assembly Bill 27. -

The Legislative Process in Texas the Legislative Process in Texas

The Legislative Process in Texas The Legislative Process in Texas Published by the Texas Legislative Council February 2021 Texas Legislative Council Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick, Joint Chair Speaker Dade Phelan, Joint Chair Jeff Archer, Executive Director The mission of the Texas Legislative Council is to provide professional, nonpartisan service and support to the Texas Legislature and legislative agencies. In every area of responsibility, we strive for quality and efficiency. During previous legislative sessions, the information in this publication was published as part of the Guide to Texas Legislative Information. Copies of this publication have been distributed in compliance with the state depository law (Subchapter G, Chapter 441, Government Code) and are available for public use through the Texas State Publications Depository Program at the Texas State Library and other state depository libraries. This publication can be found at https://www.tlc.texas.gov/publications. Additional copies of this publication may be obtained from the council: By mail: P.O. Box 12128, Austin, TX 78711-2128 By phone: (512) 463-1144 By e-mail: [email protected] By online request form (legislative offices only): https://bilreq/House.aspx If you have questions or comments regarding this publication, please contact Kellie Smith by phone at (512) 463-1155 or by e-mail at [email protected]. Table of Contents HOW A BILL ORIGINATES. .1 INTRODUCING A BILL . 1 THE ROLE OF COMMITTEES. .2 REFERRAL TO A COMMITTEE. 2 COMMITTEE MEETINGS. 2 COMMITTEE REPORTS . .3 HOUSE CALENDARS AND LIST OF ITEMS ELIGIBLE FOR CONSIDERATION. 4 SENATE REGULAR ORDER OF BUSINESS AND INTENT CALENDAR. -

Bicameralism

Bicameralism International IDEA Constitution-Building Primer 2 Bicameralism International IDEA Constitution-Building Primer 2 Elliot Bulmer © 2017 International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance (International IDEA) Second edition First published in 2014 by International IDEA International IDEA publications are independent of specific national or political interests. Views expressed in this publication do not necessarily represent the views of International IDEA, its Board or its Council members. The electronic version of this publication is available under a Creative Commons Attribute-NonCommercial- ShareAlike 3.0 (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0) licence. You are free to copy, distribute and transmit the publication as well as to remix and adapt it, provided it is only for non-commercial purposes, that you appropriately attribute the publication, and that you distribute it under an identical licence. For more information on this licence visit the Creative Commons website: <http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/> International IDEA Strömsborg SE–103 34 Stockholm Sweden Telephone: +46 8 698 37 00 Email: [email protected] Website: <http://www.idea.int> Cover design: International IDEA Cover illustration: © 123RF, <http://www.123rf.com> Produced using Booktype: <https://booktype.pro> ISBN: 978-91-7671-107-1 Contents 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................. 3 Advantages of bicameralism..................................................................................... -

The Constitution and Legislation: the Making and Changing of Laws

The Constitution and Legislation: the making and changing of laws Dr David Kenny Assistant Professor of Law, Trinity College Dublin Constitution empowers law making, and also restrains it Article 15.2.1 of the Constitution: “The sole and exclusive power of making laws for the State is hereby vested in the Oireachtas: no other legislative authority has power to make laws for the State.” 1. Law making power comes from the Constitution 2. The Oireachtas and only the Oireachtas makes law 3. A broad grant of power Constitution empowers law making, and also restrains it But only insofar as the laws accord with the Constitution Article 15.4.1 of the Constitution: “The Oireachtas shall not enact any law which is in any respect repugnant to this Constitution or any provision thereof.” Three sorts of constitutional restraint on law making The Oireachtas must: 1. Follow constitutional process for making law 2. Not breach specific prohibitions in the Constitution Article 15.5: – Imposition of the death penalty 3. Not breach broader constitutional guarantees – personal rights, eg life, property, liberty, good name How is a law made or changed? Housing Bill 2017 Step 1: Typically introduced by Minister in one House of the Oireachtas – usually the Dáil Goes through a five stage process where it is debated, in its broad principles and minute details Ends with a vote whereby the House passes or rejects the Bill Housing Bill 2017 Step 2: Moves to the other House, the Seanad, and goes through the same 5 stages The Seanad can pass the Bill; reject the Bill; -

How a Bill Becomes Law (PDF)

THIS CHART OUTLINES THE PROCESS FOR Compliments of State Representative ENACTING A BILL INTO LAW IN MISSOURI BY LEE G. SLATOR TRACING THE PATH OF A BILL INTRODUCED IN THE Gary Dusenberg - District 54 HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES. INTRODUCED IN HOUSE. READ ON BILL IS READ COMMITTEE HOLDS COMMITTEE BILL PLACED BILL IS IF PASSED, THE BILL BILL IS PLACED FINAL INTRODUCTION. ORDERED PRINTED. SECOND TIME HEARINGS. PROPONENTS CHAIR REPORTS ON BROUGHT UP IS ORDERED ON THE THIRD PASSAGE IF AND REFERRED AND OPPONENTS ARE HEARD. RECOMMENDATIONS PERFECTION FOR DEBATE PRINTED AS READING OF THE TO THE PROPER COMMITTEE CONSIDERS BILL; OF COMMITTEE CALENDAR. AND A VOTE PERFECTED. CALENDAR. BILL BY A BILL INTRODUCED IN THE SENATE COMMITTEE. MAY OFFER AMENDMENTS OR AND ANY (PERFECTION) THE IF WOULD FOLLOW THE SAME A COMMITTEE SUBSTITUTE COMMITTEE BY THE FULL AT THIRD HOUSE PASSED PROCEDURES EXCEPT THAT SENATE BILL. AMENDMENTS. HOUSE. READING, NO IS BY A THE AND HOUSE ACTION WOULD BE DEBATE IS HEARD ROLL BILL REVERSED. AND NO CALL IS CHANGES CAN BE VOTE. SENT MADE. TO THE SENATE SENATE FINAL VOTE ON BILL BY THIS TIME, HOWEVER, THE BILL MAY BE AMENDED THE SENATE DURING DEBATE AT THIRD READING. COMMITTEE CHAIR COMMITTEE HOLDS HEARINGS, READ SECOND TIME BILL IS READ FIRST TIME. IS BY ROLL REPORTS PROPONENTS AND OPPONENTS AND REFERRED TO CALL. RECOMMENDATIONS ARE HEARD. AMENDMENTS OR THE PROPER AND ANY COMMITTEE SUBSTITUTES MAY BE COMMITTEE. AMENDMENTS PROPOSED. IF IF IF IF IF BOTH HOUSES IF THE BILL PASSES BOTH IF BILL PASSES IN A IF HOUSE REJECTS IF SENATE DOES NOT IF IF THE CONFERENCE IF IF EITHER AGREE, THE BILL HOUSE AND SENATE IN DIFFERENT FORM AND CHANGES, THE BILL IS IF RECONSIDER THE REJECTS THE COMMITTEE REACHES AN IS ENROLLED IDENTICAL FORMS, THE BILL IS THE HOUSE AGREES RETURNED TO SENATE AMENDMENTS AND APPROVE AGREEMENT,THE REPORT OF REPORT, THE AND ENROLLED AND SENT TO THE TO THE FOR RECONSIDERATION. -

The Veto Override Process in Wisconsin

LEGISLATIVE REFERENCE BUREAU The Veto Override Process in Wisconsin Richard A. Champagne chief Madeline Kasper, MPA, MPH legislative analyst READING THE CONSTITUTION • August 2019, Volume 4, Number 2 © 2019 Wisconsin Legislative Reference Bureau One East Main Street, Suite 200, Madison, Wisconsin 53703 http://legis.wisconsin.gov/lrb • 608-504-5801 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, PO Box 1866, Mountain View, CA 94042, USA. he Wisconsin Constitution grants the governor the power to veto legislation.1 The governor can veto any bill in its entirety and any appropriation bill in part.2 The veto power provides the governor with a key role in the legislative process, Tone that allows the governor to check and contain the legislature’s lawmaking power. The governor’s veto power, however, is not absolute. Although the governor may veto legislation, the legislature may override a veto by a two-thirds supermajority vote. Just as the legislature’s lawmaking power is a qualified power subject to veto, the governor’s veto power is a qualified power subject to legislative override. This paper examines the legislature’s power to override executive vetoes. The paper describes the legislature’s veto override power, charts the veto override process, and dis- cusses the history of veto overrides. The paper finds that even though the legislature’s veto override power is potentially a significant limitation on the governor’s veto power, the failure of the legislature to override vetoes in recent decades has made the governor’s veto power practically invincible. -

Constitutionalism, Bicameralism, and the Control of Power

Constitutionalism, Bicameralism, and the Control of Power Constitutionalism, Bicameralism, and the Control of Power Harry Evans The Nature of Bicameralism Bicameralism is only a subset of the constitutional principle of division of power. According to that principle unlimited power vested in an individual or group will be abused; it will be used to retain power, to reward supporters and punish opponents and to divert public purposes to private ends. So power must be limited. The only satisfactory method of limitation is to divide power between different bodies with some sort of veto over each other’s actions. Only respect for another power can restrain power. To make the system last, the division is made between institutions, not people. The thesis that power corrupts its possessor may be as good a ‘law’ as any that we have in political science … . Whether exercised by a monarch or by a small group, persons who regard themselves as especially wise and virtuous are probably the worst custodians of power. Historical experience, however, is not an unrelieved record of failure to deal with the problem of power. A number of societies have succeeded in constructing political systems in which the power of the state is constrained. The key to their success lies in recognising the fact that power can only be controlled by power. This proposition leads directly to the theory of constitutional design founded upon the principle most commonly known as ‘checks and balances’.1 Inherent in this view is that it is a delusion to seek good government by ensuring the choice of wise rulers; no-one is fit to be trusted with undivided power.