The Veto Override Process in Wisconsin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

President, Prime Minister, Or Constitutional Monarch?

I McN A I R PAPERS NUMBER THREE PRESIDENT, PRIME MINISTER, OR CONSTITUTIONAL MONARCH? By EUGENE V. ROSTOW THE INSTITUTE FOR NATIONAL S~RATEGIC STUDIES I~j~l~ ~p~ 1~ ~ ~r~J~r~l~j~E~J~p~j~r~lI~1~1~L~J~~~I~I~r~ ~'l ' ~ • ~i~i ~ ,, ~ ~!~ ,,~ i~ ~ ~~ ~~ • ~ I~ ~ ~ ~i! ~H~I~II ~ ~i~ ,~ ~II~b ~ii~!i ~k~ili~Ii• i~i~II~! I ~I~I I• I~ii kl .i-I k~l ~I~ ~iI~~f ~ ~ i~I II ~ ~I ~ii~I~II ~!~•b ~ I~ ~i' iI kri ~! I ~ • r rl If r • ~I • ILL~ ~ r I ~ ~ ~Iirr~11 ¸I~' I • I i I ~ ~ ~,i~i~I•~ ~r~!i~il ~Ip ~! ~ili!~Ii!~ ~i ~I ~iI•• ~ ~ ~i ~I ~•i~,~I~I Ill~EI~ ~ • ~I ~I~ I¸ ~p ~~ ~I~i~ PRESIDENT, PRIME MINISTER, OR CONSTITUTIONAL MONARCH.'? PRESIDENT, PRIME MINISTER, OR CONSTITUTIONAL MONARCH? By EUGENE V. ROSTOW I Introduction N THE MAKING and conduct of foreign policy, ~ Congress and the President have been rivalrous part- ners for two hundred years. It is not hyperbole to call the current round of that relationship a crisis--the most serious constitutional crisis since President Franklin D. Roosevelt tried to pack the Supreme Court in 1937. Roosevelt's court-packing initiative was highly visible and the reaction to it violent and widespread. It came to an abrupt and dramatic end, some said as the result of Divine intervention, when Senator Joseph T. Robinson, the Senate Majority leader, dropped dead on the floor of the Senate while defending the President's bill. -

University of Wisconsin-Madison

For Alumni & Friends of the Nelson Institute for Environmental Studies at the University of Wisconsin–Madison SPRING 2010 Gaylord Nelson, Earth Day, and the Nelson Institute Looking back…and ahead…in a milestone year ENERGIZED! Good chemistry recharges a 30-year-old certificate program A SENSE OF PLACE Immersion experiences shape perceptions PREPARING TO ADAPT Strategizing for climate change in Wisconsin NO HIGHER CALLING Q&A with Christine Thomas Students assemble a five-story replica of Earth on Washington’s National Mall in 1995 for the Students assemble a five-story replica of Earth on Washington’s National Mall in 1995 for the 25th anniversary of Earth Day. Inset: Gaylord Nelson greets a constituent. 25th anniversary of Earth Day. Inset: Gaylord Nelson greets a constituent Together. For the planet. News and events It was a remarkable event. Twenty million Americans came together in small towns and major cities to take action on April For more news from the Nelson 22, 1970. The first Earth Day was the largest grassroots dem- Institute and details of upcoming onstration in American history. Almost overnight, the right to a events, visit our home page: clean and healthy environment, championed across time and nelson.wisc.edu the political spectrum by the likes of Theodore Roosevelt and Locate other alumni - and Rachel Carson, became the nation’s chorus. A decade of sweep- ing environmental legislation and reform followed. help us reach you Forty years later, diverse coalitions—concerned about cli- The Wisconsin Alumni Association mate change, food security, health, energy supplies, and clean offers a free online service to help water—again address local and global environmental challenges. -

The Westminster Model, Governance, and Judicial Reform

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Previously Published Works Title The Westminster Model, Governance, and Judicial Reform Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/82h2630k Journal Parliamentary Affairs, 61 Author Bevir, Mark Publication Date 2008 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California THE WESTMINSTER MODEL, GOVERNANCE, AND JUDICIAL REFORM By Mark Bevir Published in: Parliamentary Affairs 61 (2008), 559-577. I. CONTACT INFORMATION Department of Political Science, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720-1950 Email: [email protected] II. BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE Mark Bevir is a Professor in the Department of Political Science, University of California, Berkeley. He is the author of The Logic of the History of Ideas (1999) and New Labour: A Critique (2005), and co-author, with R. A. W. Rhodes, of Interpreting British Governance (2003) and Governance Stories (2006). 1 Abstract How are we to interpret judicial reform under New Labour? What are its implications for democracy? This paper argues that the reforms are part of a broader process of juridification. The Westminster Model, as derived from Dicey, upheld a concept of parliamentary sovereignty that gives a misleading account of the role of the judiciary. Juridification has arisen along with new theories and new worlds of governance that both highlight and intensify the limitations of the Westminster Model so conceived. New Labour’s judicial reforms are attempts to address problems associated with the new governance. Ironically, however, the reforms are themselves constrained by a lingering commitment to an increasingly out-dated Westminster Model. 2 THE WESTMINSTER MODEL, GOVERNANCE, AND JUDICIAL REFORM Immediately following the 1997 general election in Britain, the New Labour government started to pursue a series of radical constitutional reforms with the overt intention of making British political institutions more effective and more accountable. -

Legislative Process Lpbooklet 2016 15Th Edition.Qxp Booklet00-01 12Th Edition 11/18/16 3:00 PM Page 1

LPBkltCvr_2016_15th edition-1.qxp_BkltCvr00-01 12th edition 11/18/16 2:49 PM Page 1 South Carolina’s Legislative Process LPBooklet_2016_15th edition.qxp_Booklet00-01 12th edition 11/18/16 3:00 PM Page 1 THE LEGISLATIVE PROCESS LPBooklet_2016_15th edition.qxp_Booklet00-01 12th edition 11/18/16 3:00 PM Page 2 October 2016 15th Edition LPBooklet_2016_15th edition.qxp_Booklet00-01 12th edition 11/18/16 3:00 PM Page 3 THE LEGISLATIVE PROCESS The contents of this pamphlet consist of South Carolina’s Legislative Process , pub - lished by Charles F. Reid, Clerk of the South Carolina House of Representatives. The material is reproduced with permission. LPBooklet_2016_15th edition.qxp_Booklet00-01 12th edition 11/18/16 3:00 PM Page 4 LPBooklet_2016_15th edition.qxp_Booklet00-01 12th edition 11/18/16 3:00 PM Page 5 South Carolina’s Legislative Process HISTORY o understand the legislative process, it is nec - Tessary to know a few facts about the lawmak - ing body. The South Carolina Legislature consists of two bodies—the Senate and the House of Rep - resentatives. There are 170 members—46 Sena - tors and 124 Representatives representing dis tricts based on population. When these two bodies are referred to collectively, the Senate and House are together called the General Assembly. To be eligible to be a Representative, a person must be at least 21 years old, and Senators must be at least 25 years old. Members of the House serve for two years; Senators serve for four years. The terms of office begin on the Monday following the General Election which is held in even num - bered years on the first Tuesday after the first Monday in November. -

![The Constitution of the United States [PDF]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2214/the-constitution-of-the-united-states-pdf-432214.webp)

The Constitution of the United States [PDF]

THE CONSTITUTION oftheUnitedStates NATIONAL CONSTITUTION CENTER We the People of the United States, in Order to form a within three Years after the fi rst Meeting of the Congress more perfect Union, establish Justice, insure domestic of the United States, and within every subsequent Term of Tranquility, provide for the common defence, promote ten Years, in such Manner as they shall by Law direct. The the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty to Number of Representatives shall not exceed one for every ourselves and our Posterity, do ordain and establish this thirty Thousand, but each State shall have at Least one Constitution for the United States of America. Representative; and until such enumeration shall be made, the State of New Hampshire shall be entitled to chuse three, Massachusetts eight, Rhode-Island and Providence Plantations one, Connecticut fi ve, New-York six, New Jersey four, Pennsylvania eight, Delaware one, Maryland Article.I. six, Virginia ten, North Carolina fi ve, South Carolina fi ve, and Georgia three. SECTION. 1. When vacancies happen in the Representation from any All legislative Powers herein granted shall be vested in a State, the Executive Authority thereof shall issue Writs of Congress of the United States, which shall consist of a Sen- Election to fi ll such Vacancies. ate and House of Representatives. The House of Representatives shall chuse their SECTION. 2. Speaker and other Offi cers; and shall have the sole Power of Impeachment. The House of Representatives shall be composed of Mem- bers chosen every second Year by the People of the several SECTION. -

How a Bill Becomes 4

WELCOME TO THE WISCONSIN STATE ASSEMBLY ince becoming a state in 1848, Wisconsin has continued to demonstrate strong leadership and democracy. Because TABLE OF CONTENTS S 2 ...... Introduction of this proud history, our state has been looked to repeatedly as a national leader in government 4 ...... “The Law Needs to Change” innovation and reform. “How A Bill Becomes 4 ...... WisconsinEye Provides View of the Legislature Law” was created to help visitors understand 5 ...... Deliberation and Examination Wisconsin’s legislative process and provide 5 ...... Making a Good Idea Better suggestions on how citizens can participate in 6 ...... The Importance of Caucuses that process. This booklet explains how one idea 7 ...... First & Second Reading or inspiration becomes a bill and moves through 7 ...... Third Reading and Passage the legislative process and into the law books. 7 ...... On to the Senate It is a long road from initial development of an 8 ...... Assembly Bill 27 idea to the emergence of a new law. During 9 ...... Approval of the Governor and Into the Law Books consideration, the bill will be scrutinized and 9 ...... Conclusion examined, criticized and praised. It will be 10 .... Staying in Touch–How to Contact changed, improved, strengthened, and even Your State Representative weakened. If passed, it will undergo the ultimate 11 .... Find Information Online test of merit—time. 12 .... “How a Bill Becomes Law” Cartoon 13 .... “How a Bill Becomes Law” Flow Chart *Words in bold print are defined in the Glossary at the back of the booklet. 14 .... Glossary In this booklet, the bill used as an example of “How a Bill Becomes Law” is 2015 Assembly Bill 27. -

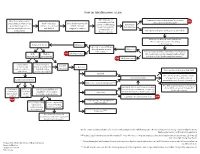

Idea Becomes a Law

How an Idea Becomes a Law Bill is introduced Ideas from many sources: Committee reports “do not pass” or does not STOP and undergoes First constituents, interest groups, Author requests Bill is filed electronically take action on the measure.* and Second Readings. Committee government agencies, bill to be researched with Clerk and is Speaker assigns it to Consideration interim studies, businesses, and drafted. assigned a number. committee(s) or the Governor. Bill reported “do pass” or “do pass as amended.” direct to calendar. Bill moves to General Order. Available to Floor Leader for possible scheduling Returned to House Bill passes on Floor Agenda. Engrossed to Senate: Bill goes through similar process Bill passes in the Senate. ** Floor Consideration: Bill scheduled on Floor Agenda. With Without STOP Bill does not pass Bill is explained, possibly amended, debated, and amendments amendments voted upon. Third Reading and final passage. ** STOP Bill does not pass House refuses House concurs in Enrolled to concur and Senate amendments. To Governor to Governor requests conference Fourth Reading Becomes law on date specified in bill with Senate. and final passage.** Signs bill If no date is specified, and bill contains To Secretary of State emergency clause, bill is effective Conference Committee immediately upon Governor’s signature. Bill becomes law without signature*** If no date is specified, and no emergency Two-thirds vote in each house to override clause, bill becomes law 90 days after Conference CCR filed: CCR electronically filed and veto, unless passed with an emergency, sine die adjournment. Committee Conferees available for Floor Leader Vetoes bill which then requires a three-fourths vote. -

Chapter 57 Veto of Bills

Chapter 57 Veto of Bills § 1. In General; Veto Messages § 2. House Action on Vetoed Bills § 3. — Consideration as Privileged § 4. — Motions in Order § 5. — Debate § 6. — Voting; Disposition of Bill § 7. Pocket Vetoes § 8. Line Item Veto Authority Research References U.S. Const. art. I § 7 4 Hinds §§ 3520–3552 7 Cannon §§ 1094–1115 Deschler Ch 24 §§ 17–23 Manual §§ 104, 107–109, 112–114, 1130(6B) § 1. In General; Veto Messages Generally The authority for the President to disapprove, or veto, a bill is spelled out in article I, section 7 of the Constitution. The same clause addresses the process by which the Congress can override a veto and enact a measure into law. The President has a 10-day period in which to approve or disapprove a bill. He can sign the bill into law or he can return it to the House of its origination with a veto message detailing why he chooses not to sign. If he fails to give his approval by affixing his signature during that period, the bill will become law automatically, without his signature. However, in very limited circumstances the President may, by withholding his signature, effect a ‘‘pocket veto.’’ If before the end of a 10-day signing period the Congress adjourns sine die and thereby prevents the return of the bill, the bill does not become law if the President has taken no action regarding it. At this stage, the bill can become a law only if the President signs it. Deschler Ch 24 § 17. For a discussion of pocket vetoes, see § 7, infra. -

Feature Article

3 ABOUT WISCONSIN 282 | Wisconsin Blue Book 2019–2020 Menomonie residents celebrated local members of the Wisconsin National Guard who served during the Great War. As Wisconsin soldiers demobilized, policymakers reevaluated the meaning of wartime service—and fiercely debated how the state should recognize veterans’ sacrifices. WHS IMAGE ID 103418 A Hero’s Welcome How the 1919 Wisconsin Legislature overcame divisions to enact innovative veterans legislation following World War I. BY JILLIAN SLAIGHT he Great War seemed strangely distant to Ira Lee Peterson, even as his unit camped mere miles from the front lines in France. Between drills and marches, the twenty-two-year-old Wisconsinite swam in streams, wrote letters home, and slept underneath the stars in apple orchards. TEven in the trenches, the morning of Sunday, June 16, 1918, was “so quiet . that all one could hear was the rats running around bumping into cans and wire.” Peterson sat reading a book until a “whizzing sound” cut through the silence, announcing a bombardment that sent him and his comrades scurrying “quick as gophers” into their dugout.1 After this “baptism with shell fire,” Peterson suffered a succession of horrors: mustard gas inhalation, shrapnel wounds, and a German 283 | Wisconsin Blue Book 2019–2020 COURTESY LINDA PALMER PALMER LINDA COURTESY WILLIAM WESSA, LANGLADE COUNTY HISTORICAL SOCIETY HISTORICAL COUNTY LANGLADE WESSA, WILLIAM Before 1914, faith in scientific progress led people to believe that twentieth-century war would be less brutal. In reality, new technologies resulted in unprecedented death and disability. (left) American soldiers suffered the effects of chemical warfare despite training in the use of gas masks. -

The Congressional Veto: Preserving the Constitutional Framework

Indiana Law Journal Volume 52 Issue 2 Article 5 Winter 1977 The Congressional Veto: Preserving the Constitutional Framework Arthur S. Miller George Washington University George M. Knapp George Washington University Follow this and additional works at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ilj Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, Courts Commons, Legislation Commons, and the President/ Executive Department Commons Recommended Citation Miller, Arthur S. and Knapp, George M. (1977) "The Congressional Veto: Preserving the Constitutional Framework," Indiana Law Journal: Vol. 52 : Iss. 2 , Article 5. Available at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ilj/vol52/iss2/5 This Symposium is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School Journals at Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Indiana Law Journal by an authorized editor of Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Congressional Veto: Preserving the Constitutional Framework ARTHUR S. MILLER* & GEORGE M. KNAPP** The men who met in Philadelphia in the summer of 1787 were practical statesmen, experienced in politics, who viewed the principle of separation of powers as a vital check against tyranny. But they likewise saw that a hermetic sealing off of the three branches of government would preclude the establishment of a Nation capable of governing itself effectively., INTRODUCTION This article analyzes a recent important development in the division of powers between Congress and the Executive. It is more speculative than exhaustive. The aim is to provide a different perspective on a basic constitutional concept. It is assumed that the "practical statesmen" who wrote the Constitution must have sought to establish a system of government which encouraged interbranch cooperation and abhorred unnecessary conflict. -

Direct Primary Care State Approaches to Regulating Subscription-Based Medicine

LEGISLATIVE REFERENCE BUREAU Direct Primary Care State Approaches to Regulating Subscription-Based Medicine Jessie Gibbons legislative analyst WISCONSIN POLICY PROJECT • January 2020, Volume 3, Number 2 © 2020 Wisconsin Legislative Reference Bureau One East Main Street, Suite 200, Madison, Wisconsin 53703 http://legis.wisconsin.gov/lrb • 608-504-5801 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, PO Box 1866, Mountain View, CA 94042, USA. Overview Direct Primary Care (DPC) is a health care payment model in which physicians contract directly with patients to provide care outside the traditional insurance-based system. In- stead of billing health insurers, DPC providers charge their subscribers a monthly fee per individual, ranging from approximately $25 to $125 per person. In exchange, subscrib- ers receive unlimited primary care services—including physical exams, management of chronic diseases, and diagnoses of acute illness—usually at no additional cost. Dozens of DPC providers are currently practicing in Wisconsin, and many physi- cians and patients who are using the model are satisfied with it. Patients appreciate that they can spend more time with their physicians and have more immediate access to care, while physicians like that the model allows them to streamline their practices and reduce the administrative burden of billing health insurers. However, many stakeholders in the health care industry have expressed concerns about the DPC model being a duplicative and unregulated form of health insurance. In Wisconsin, medical practices currently using the DPC payment model are oper- ating legally, and the agreements between patients and providers vary from practice to practice. -

Wisconsin in La Crosse

CONTENTS Wisconsin History Timeline. 3 Preface and Acknowledgments. 4 SPIRIT OF David J. Marcou Birth of the Republican Party . 5 Former Governor Lee S. Dreyfus Rebirth of the Democratic Party . 6 Former Governor Patrick J. Lucey WISCONSIN On Wisconsin! . 7 A Historical Photo-Essay Governor James Doyle Wisconsin in the World . 8 of the Badger State 1 David J. Marcou Edited by David J. Marcou We Are Wisconsin . 18 for the American Writers and Photographers Alliance, 2 Professor John Sharpless with Prologue by Former Governor Lee S. Dreyfus, Introduction by Former Governor Patrick J. Lucey, Wisconsin’s Natural Heritage . 26 Foreword by Governor James Doyle, 3 Jim Solberg and Technical Advice by Steve Kiedrowski Portraits and Wisconsin . 36 4 Dale Barclay Athletes, Artists, and Workers. 44 5 Steve Kiedrowski & David J. Marcou Faith in Wisconsin . 54 6 Fr. Bernard McGarty Wisconsinites Who Serve. 62 7 Daniel J. Marcou Communities and Families . 72 8 tamara Horstman-Riphahn & Ronald Roshon, Ph.D. Wisconsin in La Crosse . 80 9 Anita T. Doering Wisconsin in America . 90 10 Roberta Stevens America’s Dairyland. 98 11 Patrick Slattery Health, Education & Philanthropy. 108 12 Kelly Weber Firsts and Bests. 116 13 Nelda Liebig Fests, Fairs, and Fun . 126 14 Terry Rochester Seasons and Metaphors of Life. 134 15 Karen K. List Building Bridges of Destiny . 144 Yvonne Klinkenberg SW book final 1 5/22/05, 4:51 PM Spirit of Wisconsin: A Historical Photo-Essay of the Badger State Copyright © 2005—for entire book: David J. Marcou and Matthew A. Marcou; for individual creations included in/on this book: individual creators.