Regular Vetoes and Pocket Vetoes: in Brief

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

President, Prime Minister, Or Constitutional Monarch?

I McN A I R PAPERS NUMBER THREE PRESIDENT, PRIME MINISTER, OR CONSTITUTIONAL MONARCH? By EUGENE V. ROSTOW THE INSTITUTE FOR NATIONAL S~RATEGIC STUDIES I~j~l~ ~p~ 1~ ~ ~r~J~r~l~j~E~J~p~j~r~lI~1~1~L~J~~~I~I~r~ ~'l ' ~ • ~i~i ~ ,, ~ ~!~ ,,~ i~ ~ ~~ ~~ • ~ I~ ~ ~ ~i! ~H~I~II ~ ~i~ ,~ ~II~b ~ii~!i ~k~ili~Ii• i~i~II~! I ~I~I I• I~ii kl .i-I k~l ~I~ ~iI~~f ~ ~ i~I II ~ ~I ~ii~I~II ~!~•b ~ I~ ~i' iI kri ~! I ~ • r rl If r • ~I • ILL~ ~ r I ~ ~ ~Iirr~11 ¸I~' I • I i I ~ ~ ~,i~i~I•~ ~r~!i~il ~Ip ~! ~ili!~Ii!~ ~i ~I ~iI•• ~ ~ ~i ~I ~•i~,~I~I Ill~EI~ ~ • ~I ~I~ I¸ ~p ~~ ~I~i~ PRESIDENT, PRIME MINISTER, OR CONSTITUTIONAL MONARCH.'? PRESIDENT, PRIME MINISTER, OR CONSTITUTIONAL MONARCH? By EUGENE V. ROSTOW I Introduction N THE MAKING and conduct of foreign policy, ~ Congress and the President have been rivalrous part- ners for two hundred years. It is not hyperbole to call the current round of that relationship a crisis--the most serious constitutional crisis since President Franklin D. Roosevelt tried to pack the Supreme Court in 1937. Roosevelt's court-packing initiative was highly visible and the reaction to it violent and widespread. It came to an abrupt and dramatic end, some said as the result of Divine intervention, when Senator Joseph T. Robinson, the Senate Majority leader, dropped dead on the floor of the Senate while defending the President's bill. -

The Westminster Model, Governance, and Judicial Reform

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Previously Published Works Title The Westminster Model, Governance, and Judicial Reform Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/82h2630k Journal Parliamentary Affairs, 61 Author Bevir, Mark Publication Date 2008 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California THE WESTMINSTER MODEL, GOVERNANCE, AND JUDICIAL REFORM By Mark Bevir Published in: Parliamentary Affairs 61 (2008), 559-577. I. CONTACT INFORMATION Department of Political Science, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720-1950 Email: [email protected] II. BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE Mark Bevir is a Professor in the Department of Political Science, University of California, Berkeley. He is the author of The Logic of the History of Ideas (1999) and New Labour: A Critique (2005), and co-author, with R. A. W. Rhodes, of Interpreting British Governance (2003) and Governance Stories (2006). 1 Abstract How are we to interpret judicial reform under New Labour? What are its implications for democracy? This paper argues that the reforms are part of a broader process of juridification. The Westminster Model, as derived from Dicey, upheld a concept of parliamentary sovereignty that gives a misleading account of the role of the judiciary. Juridification has arisen along with new theories and new worlds of governance that both highlight and intensify the limitations of the Westminster Model so conceived. New Labour’s judicial reforms are attempts to address problems associated with the new governance. Ironically, however, the reforms are themselves constrained by a lingering commitment to an increasingly out-dated Westminster Model. 2 THE WESTMINSTER MODEL, GOVERNANCE, AND JUDICIAL REFORM Immediately following the 1997 general election in Britain, the New Labour government started to pursue a series of radical constitutional reforms with the overt intention of making British political institutions more effective and more accountable. -

Legislative Process Lpbooklet 2016 15Th Edition.Qxp Booklet00-01 12Th Edition 11/18/16 3:00 PM Page 1

LPBkltCvr_2016_15th edition-1.qxp_BkltCvr00-01 12th edition 11/18/16 2:49 PM Page 1 South Carolina’s Legislative Process LPBooklet_2016_15th edition.qxp_Booklet00-01 12th edition 11/18/16 3:00 PM Page 1 THE LEGISLATIVE PROCESS LPBooklet_2016_15th edition.qxp_Booklet00-01 12th edition 11/18/16 3:00 PM Page 2 October 2016 15th Edition LPBooklet_2016_15th edition.qxp_Booklet00-01 12th edition 11/18/16 3:00 PM Page 3 THE LEGISLATIVE PROCESS The contents of this pamphlet consist of South Carolina’s Legislative Process , pub - lished by Charles F. Reid, Clerk of the South Carolina House of Representatives. The material is reproduced with permission. LPBooklet_2016_15th edition.qxp_Booklet00-01 12th edition 11/18/16 3:00 PM Page 4 LPBooklet_2016_15th edition.qxp_Booklet00-01 12th edition 11/18/16 3:00 PM Page 5 South Carolina’s Legislative Process HISTORY o understand the legislative process, it is nec - Tessary to know a few facts about the lawmak - ing body. The South Carolina Legislature consists of two bodies—the Senate and the House of Rep - resentatives. There are 170 members—46 Sena - tors and 124 Representatives representing dis tricts based on population. When these two bodies are referred to collectively, the Senate and House are together called the General Assembly. To be eligible to be a Representative, a person must be at least 21 years old, and Senators must be at least 25 years old. Members of the House serve for two years; Senators serve for four years. The terms of office begin on the Monday following the General Election which is held in even num - bered years on the first Tuesday after the first Monday in November. -

![The Constitution of the United States [PDF]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2214/the-constitution-of-the-united-states-pdf-432214.webp)

The Constitution of the United States [PDF]

THE CONSTITUTION oftheUnitedStates NATIONAL CONSTITUTION CENTER We the People of the United States, in Order to form a within three Years after the fi rst Meeting of the Congress more perfect Union, establish Justice, insure domestic of the United States, and within every subsequent Term of Tranquility, provide for the common defence, promote ten Years, in such Manner as they shall by Law direct. The the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty to Number of Representatives shall not exceed one for every ourselves and our Posterity, do ordain and establish this thirty Thousand, but each State shall have at Least one Constitution for the United States of America. Representative; and until such enumeration shall be made, the State of New Hampshire shall be entitled to chuse three, Massachusetts eight, Rhode-Island and Providence Plantations one, Connecticut fi ve, New-York six, New Jersey four, Pennsylvania eight, Delaware one, Maryland Article.I. six, Virginia ten, North Carolina fi ve, South Carolina fi ve, and Georgia three. SECTION. 1. When vacancies happen in the Representation from any All legislative Powers herein granted shall be vested in a State, the Executive Authority thereof shall issue Writs of Congress of the United States, which shall consist of a Sen- Election to fi ll such Vacancies. ate and House of Representatives. The House of Representatives shall chuse their SECTION. 2. Speaker and other Offi cers; and shall have the sole Power of Impeachment. The House of Representatives shall be composed of Mem- bers chosen every second Year by the People of the several SECTION. -

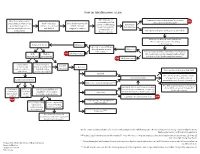

Idea Becomes a Law

How an Idea Becomes a Law Bill is introduced Ideas from many sources: Committee reports “do not pass” or does not STOP and undergoes First constituents, interest groups, Author requests Bill is filed electronically take action on the measure.* and Second Readings. Committee government agencies, bill to be researched with Clerk and is Speaker assigns it to Consideration interim studies, businesses, and drafted. assigned a number. committee(s) or the Governor. Bill reported “do pass” or “do pass as amended.” direct to calendar. Bill moves to General Order. Available to Floor Leader for possible scheduling Returned to House Bill passes on Floor Agenda. Engrossed to Senate: Bill goes through similar process Bill passes in the Senate. ** Floor Consideration: Bill scheduled on Floor Agenda. With Without STOP Bill does not pass Bill is explained, possibly amended, debated, and amendments amendments voted upon. Third Reading and final passage. ** STOP Bill does not pass House refuses House concurs in Enrolled to concur and Senate amendments. To Governor to Governor requests conference Fourth Reading Becomes law on date specified in bill with Senate. and final passage.** Signs bill If no date is specified, and bill contains To Secretary of State emergency clause, bill is effective Conference Committee immediately upon Governor’s signature. Bill becomes law without signature*** If no date is specified, and no emergency Two-thirds vote in each house to override clause, bill becomes law 90 days after Conference CCR filed: CCR electronically filed and veto, unless passed with an emergency, sine die adjournment. Committee Conferees available for Floor Leader Vetoes bill which then requires a three-fourths vote. -

Chapter 57 Veto of Bills

Chapter 57 Veto of Bills § 1. In General; Veto Messages § 2. House Action on Vetoed Bills § 3. — Consideration as Privileged § 4. — Motions in Order § 5. — Debate § 6. — Voting; Disposition of Bill § 7. Pocket Vetoes § 8. Line Item Veto Authority Research References U.S. Const. art. I § 7 4 Hinds §§ 3520–3552 7 Cannon §§ 1094–1115 Deschler Ch 24 §§ 17–23 Manual §§ 104, 107–109, 112–114, 1130(6B) § 1. In General; Veto Messages Generally The authority for the President to disapprove, or veto, a bill is spelled out in article I, section 7 of the Constitution. The same clause addresses the process by which the Congress can override a veto and enact a measure into law. The President has a 10-day period in which to approve or disapprove a bill. He can sign the bill into law or he can return it to the House of its origination with a veto message detailing why he chooses not to sign. If he fails to give his approval by affixing his signature during that period, the bill will become law automatically, without his signature. However, in very limited circumstances the President may, by withholding his signature, effect a ‘‘pocket veto.’’ If before the end of a 10-day signing period the Congress adjourns sine die and thereby prevents the return of the bill, the bill does not become law if the President has taken no action regarding it. At this stage, the bill can become a law only if the President signs it. Deschler Ch 24 § 17. For a discussion of pocket vetoes, see § 7, infra. -

2021 Panel Systems Catalog

Table of Contents Page Title Page Number Terms and Conditions 3 - 4 Specifications 5 2.0 and SB3 Panel System Options 16 - 17 Wood Finish Options 18 Standard Textile Options 19 2.0 Paneling System Fabric Panel with Wooden Top Cap 6 - 7 Fabric Posts and Wooden End Caps 8 - 9 SB3 Paneling System Fabric Panel with Wooden Top Cap 10 - 11 Fabric Posts with Wooden Top Cap 12 - 13 Wooden Posts 14 - 15 revision 1.0 - 12/2/2020 Terms and Conditions 1. Terms of Payment ∙Qualified Customers will have Net 30 days from date of order completion, and a 1% discount if paid within 10 days of the invoice date. ∙Customers lacking credentials may be required down payment or deposit in full prior to production. ∙Finance charges of 2% will be applied to each invoice past 30 days. ∙Terms of payment will apply unless modified in writing by Custom Office Design, Inc. 2. Pricing ∙All pricing is premised on product that is made available for will call to the buyer pre-assembled and unpackaged from our base of operations in Auburn, WA. ∙Prices subject to change without notice. Price lists noting latest date supersedes all previously published price lists. Pricing does not include A. Delivery, Installation, or Freight-handling charges. B. Product Packaging, or Crating charges. C. Custom Product Detail upcharge. D. Special-Order/Non-standard Laminate, Fabric, Staining and/or Labor upcharge. E. On-site service charges. F. Federal, state or local taxes. 3. Ordering A. All orders must be made in writing and accompanied with a corresponding purchase order. -

The Congressional Veto: Preserving the Constitutional Framework

Indiana Law Journal Volume 52 Issue 2 Article 5 Winter 1977 The Congressional Veto: Preserving the Constitutional Framework Arthur S. Miller George Washington University George M. Knapp George Washington University Follow this and additional works at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ilj Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, Courts Commons, Legislation Commons, and the President/ Executive Department Commons Recommended Citation Miller, Arthur S. and Knapp, George M. (1977) "The Congressional Veto: Preserving the Constitutional Framework," Indiana Law Journal: Vol. 52 : Iss. 2 , Article 5. Available at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ilj/vol52/iss2/5 This Symposium is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School Journals at Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Indiana Law Journal by an authorized editor of Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Congressional Veto: Preserving the Constitutional Framework ARTHUR S. MILLER* & GEORGE M. KNAPP** The men who met in Philadelphia in the summer of 1787 were practical statesmen, experienced in politics, who viewed the principle of separation of powers as a vital check against tyranny. But they likewise saw that a hermetic sealing off of the three branches of government would preclude the establishment of a Nation capable of governing itself effectively., INTRODUCTION This article analyzes a recent important development in the division of powers between Congress and the Executive. It is more speculative than exhaustive. The aim is to provide a different perspective on a basic constitutional concept. It is assumed that the "practical statesmen" who wrote the Constitution must have sought to establish a system of government which encouraged interbranch cooperation and abhorred unnecessary conflict. -

Report on the Draft Investigatory Powers Bill

Intelligence and Security Committee of Parliament Report on the draft Investigatory Powers Bill Chair: The Rt. Hon. Dominic Grieve QC MP Intelligence and Security Committee of Parliament Report on the draft Investigatory Powers Bill Chair: The Rt. Hon. Dominic Grieve QC MP Presented to Parliament pursuant to Section 3 of the Justice and Security Act 2013 Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed on 9 February 2016 HC 795 © Crown copyright 2016 This publication is licensed under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/version/3 or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email: [email protected]. Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. This publication is available at www.gov.uk/government/publications Any enquiries regarding this publication should be sent to us via isc.independent.gov.uk/contact Print ISBN 9781474127714 Web ISBN 9781474127721 ID 26011601 02/16 53894 19585 Printed on paper containing 75% recycled fibre content minimum Printed in the UK by the Williams Lea Group on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office THE INTELLIGENCE AND SECURITY COMMITTEE OF PARLIAMENT The Rt. Hon. Dominic Grieve QC MP (Chair) The Rt. Hon. Sir Alan Duncan KCMG MP The Rt. Hon. Fiona Mactaggart MP The Rt. Hon. George Howarth MP The Rt. Hon. Angus Robertson MP The Rt. Hon. the Lord Janvrin GCB GCVO QSO The Rt. -

City of Glasgow Ordinance No. 2809 an Ordinance

CITY OF GLASGOW ORDINANCE NO. 2809 AN ORDINANCE ESTABLISHING THE CITY OF GLASGOW’S STORMWATER MANAGEMENT PROGRAM, THE STORMWATER FUND, THE STORMWATER MANAGEMENT FEE, BILLING PROCEDURES, CLASSIFICATION OF PROPERTY AND REQUEST FOR CORRECTION PROCEDURES. WHEREAS, the City of Glasgow maintains a system of storm and surface water management facilities including but not limited to, inlets, conduits, manholes, channels, ditches, drainage easements, retention and detention basins, infiltration facilities, and other components, as well as natural waterways and WHEREAS, the stormwater system in the City requires regular maintenance and improvements and WHEREAS, stormwater quality is degraded due to erosion and the discharge of nutrients, metals, oil, grease, toxic materials, and other substances into and through the stormwater system and WHEREAS, the public health, safety, and welfare is adversely affected by poor ambient water quality and flooding and WHEREAS, all real property in the City of Glasgow either uses or benefits from the maintenance of the stormwater system and WHEREAS, the extent of use of the stormwater system by each property is dependent on factors that influence runoff, including land use and the amount of impervious surface on the property and WHEREAS, the cost of improving, maintaining, operating and monitoring the stormwater system should be allocated, to the extent practicable, to all property owners based on the impact of runoff from the impervious areas of their property on the stormwater management system and WHEREAS, management -

5115-S.E Hbr Aph 21

HOUSE BILL REPORT ESSB 5115 As Passed House - Amended: April 5, 2021 Title: An act relating to establishing health emergency labor standards. Brief Description: Establishing health emergency labor standards. Sponsors: Senate Committee on Labor, Commerce & Tribal Affairs (originally sponsored by Senators Keiser, Liias, Conway, Kuderer, Lovelett, Nguyen, Salomon, Stanford and Wilson, C.). Brief History: Committee Activity: Labor & Workplace Standards: 3/12/21, 3/24/21 [DPA]. Floor Activity: Passed House: 4/5/21, 68-30. Brief Summary of Engrossed Substitute Bill (As Amended By House) • Creates an occupational disease presumption, for the purposes of workers' compensation, for frontline employees during a public health emergency. • Requires certain employers to notify the Department of Labor and Industries when 10 or more employees have tested positive for the infectious disease during a public health emergency. • Requires employers to provide written notice to employees of potential exposure to the infectious disease during a public health emergency. • Prohibits discrimination against high-risk employees who seek accommodations or use leave options. HOUSE COMMITTEE ON LABOR & WORKPLACE STANDARDS This analysis was prepared by non-partisan legislative staff for the use of legislative members in their deliberations. This analysis is not part of the legislation nor does it constitute a statement of legislative intent. House Bill Report - 1 - ESSB 5115 Majority Report: Do pass as amended. Signed by 6 members: Representatives Sells, Chair; Berry, Vice Chair; Hoff, Ranking Minority Member; Bronoske, Harris and Ortiz- Self. Minority Report: Without recommendation. Signed by 1 member: Representative Mosbrucker, Assistant Ranking Minority Member. Staff: Trudes Tango (786-7384). Background: Workers' Compensation. Workers who are injured in the course of employment or who are affected by an occupational disease are entitled to workers' compensation benefits, which may include medical, temporary time-loss, and other benefits. -

The Legislative Veto: Is It Legislation?

Washington and Lee Law Review Volume 38 | Issue 1 Article 13 Winter 1-1-1981 The Legislative Veto: Is It Legislation? Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.wlu.edu/wlulr Part of the Legislation Commons Recommended Citation The Legislative Veto: Is It Legislation?, 38 Wash. & Lee L. Rev. 172 (1981), https://scholarlycommons.law.wlu.edu/wlulr/vol38/iss1/13 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Washington and Lee Law Review at Washington & Lee University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington and Lee Law Review by an authorized editor of Washington & Lee University School of Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE LEGISLATIVE VETO: IS IT LEGISLATION? The complexity of the law-making process and the need for legislative efficiency have compelled legislatures to delegate authority to administrative agencies and departments.1 The delegation of the legislative power has raised important constitutional issues.2 The United States Constitution divides the federal government into three branches.' Each branch has specific powers and responsibilities.' The doctrine of separation of powers demands that each branch carry out only those functions designated by the Constitution.' The delegation of the legislative authority to executive administrative agencies, therefore, may constitute a violation of the separation of powers doctrine.6 For the most part, however, the Supreme Court has sanctioned such delegation.' ' See Stone, The Twentieth Century AdministrativeExplosion and After, 52 CALIF. L. REV. 513, 518-19 (1964). Stone has expressed the belief that the growth of administrative law is a response to legislative shortfalls.