The Inefficiency of Splitting the Bill*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2017 ANNUAL REPORT 2017 Annual Report Table of Contents the Michael J

Roadmaps for Progress 2017 ANNUAL REPORT 2017 Annual Report Table of Contents The Michael J. Fox Foundation is dedicated to finding a cure for 2 A Note from Michael Parkinson’s disease through an 4 Annual Letter from the CEO and the Co-Founder aggressively funded research agenda 6 Roadmaps for Progress and to ensuring the development of 8 2017 in Photos improved therapies for those living 10 2017 Donor Listing 16 Legacy Circle with Parkinson’s today. 18 Industry Partners 26 Corporate Gifts 32 Tributees 36 Recurring Gifts 39 Team Fox 40 Team Fox Lifetime MVPs 46 The MJFF Signature Series 47 Team Fox in Photos 48 Financial Highlights 54 Credits 55 Boards and Councils Milestone Markers Throughout the book, look for stories of some of the dedicated Michael J. Fox Foundation community members whose generosity and collaboration are moving us forward. 1 The Michael J. Fox Foundation 2017 Annual Report “What matters most isn’t getting diagnosed with Parkinson’s, it’s A Note from what you do next. Michael J. Fox The choices we make after we’re diagnosed Dear Friend, can open doors to One of the great gifts of my life is that I've been in a position to take my experience with Parkinson's and combine it with the perspectives and expertise of others to accelerate possibilities you’d improved treatments and a cure. never imagine.’’ In 2017, thanks to your generosity and fierce belief in our shared mission, we moved closer to this goal than ever before. For helping us put breakthroughs within reach — thank you. -

Mustang Daily, May 26, 1995

CALIFORNIA POLYTECHNIC STATE UNIVERSITY SAN LUIS OBISPO M u s t a n g D a i i y MAY 26, 1995 VOLUME UX, No. 131 FRIDAY Drummer boy ASI members who ditch meetings 'V f' " ' Í’* »' ■ may lose perks ■iè 4' ■ rf' ^ * By Jason D. Plenions In the past, members were Daily Staff Wiitei still required by ASI bylaws to attend the official meetings, but ASI will make it tougher for there was no requirement to at its board members to use their tend the workshops. perks next year. 1 màt In the ASI Board of Director’s meeting on Wednesday — the last of the year — the board "This is a good bill. ASI ■■■ ■ : ■<■.< '■■■ ■■ - passed a bill requiring its mem bers to be in “good standing” to needs its members to be .J."-:- receive free admission to some present to function well, ASI-sponsored events, including •t* ' ’ i i ’ 1, ' mm and this bill should encour - - v'V the Cal Poly Rodeo. u According to the bill, its pur age th a t/ pose is to increase attendance by board members to various workshops and general meetings. Steve McShane Workshops are desigpied to provide an arena of discussion College of Agriculture rep. for board members to educate themselves on proposed legisla tion, and are considered volun “This is a good bill,” said tary. Steve McShane, a College of # The “good standing” require Agriculture representative. “ASI ment will be met by a member needs its members to be present whose attendance record shows to function well, and this bill they have attended at least 60 should encourage that.” percent of all meetings, accord Some, however, feel the bill ing to the bill. -

Surprise Billing National Poll Report FINAL

Surprise Medical Bills Results from a National Survey November 2019 National 12-minute survey of 1,000 registered voters using YouGov’s national online panel fielded October 16 - 22, 2019. Margin of sampling error on the total results: +/-3.3 percentage points. Methods. The study was sponsored by Families USA, a leading national, non-partisan voice for health care consumers. PerryUndem, a non-partisan research firm, conducted the survey. The survey explored voters’ experiences with surprise medical bills and their feelings about legislation to protect consumers from these bills. 2 5 Key Findings. 1. Surprise medical bills are a common 2. Across party lines, nearly 9 in 10 voters experience for more than 4 in 10 voters. support legislation to protect patients from surprise medical bills. More than 4 in 10 (44%) have received a surprise out of network bill and among Early in the survey, 89% of voters support this group, nearly 8 in 10 say it was “Congress passing federal legislation to difficult to pay (68%) or that they couldn’t protect patients from surprise medical pay the bill at all (11%). bills.” Near the end of the survey, 87% feel it is “important” that their elected officials support legislation to protect patients from surprise medical bills. Those saying it is important include Democrats 97%; Independents 88%; and Republicans 74%. 3 5 Key Findings (cont’d). 3. Voters prefer, more than 9 to 1, a bill that 4. Voters are not concerned about doctors pays doctors and hospitals based on and hospitals being paid less money. what doctors in the area are typically paid and would be less likely to lead to higher Almost 9 in 10 (86%) voters say their fees premiums. -

Philippines's Constitution of 1987

PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:44 constituteproject.org Philippines's Constitution of 1987 This complete constitution has been generated from excerpts of texts from the repository of the Comparative Constitutions Project, and distributed on constituteproject.org. constituteproject.org PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:44 Table of contents Preamble . 3 ARTICLE I: NATIONAL TERRITORY . 3 ARTICLE II: DECLARATION OF PRINCIPLES AND STATE POLICIES PRINCIPLES . 3 ARTICLE III: BILL OF RIGHTS . 6 ARTICLE IV: CITIZENSHIP . 9 ARTICLE V: SUFFRAGE . 10 ARTICLE VI: LEGISLATIVE DEPARTMENT . 10 ARTICLE VII: EXECUTIVE DEPARTMENT . 17 ARTICLE VIII: JUDICIAL DEPARTMENT . 22 ARTICLE IX: CONSTITUTIONAL COMMISSIONS . 26 A. COMMON PROVISIONS . 26 B. THE CIVIL SERVICE COMMISSION . 28 C. THE COMMISSION ON ELECTIONS . 29 D. THE COMMISSION ON AUDIT . 32 ARTICLE X: LOCAL GOVERNMENT . 33 ARTICLE XI: ACCOUNTABILITY OF PUBLIC OFFICERS . 37 ARTICLE XII: NATIONAL ECONOMY AND PATRIMONY . 41 ARTICLE XIII: SOCIAL JUSTICE AND HUMAN RIGHTS . 45 ARTICLE XIV: EDUCATION, SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY, ARTS, CULTURE, AND SPORTS . 49 ARTICLE XV: THE FAMILY . 53 ARTICLE XVI: GENERAL PROVISIONS . 54 ARTICLE XVII: AMENDMENTS OR REVISIONS . 56 ARTICLE XVIII: TRANSITORY PROVISIONS . 57 Philippines 1987 Page 2 constituteproject.org PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:44 • Source of constitutional authority • General guarantee of equality Preamble • God or other deities • Motives for writing constitution • Preamble We, the sovereign Filipino people, imploring the aid of Almighty God, in order to build a just and humane society and establish a Government that shall embody our ideals and aspirations, promote the common good, conserve and develop our patrimony, and secure to ourselves and our posterity the blessings of independence and democracy under the rule of law and a regime of truth, justice, freedom, love, equality, and peace, do ordain and promulgate this Constitution. -

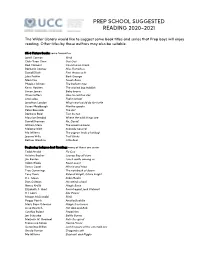

Prep School Suggested Reading 2020-2021

PREP SCHOOL SUGGESTED READING 2020-2021 The Wilder Library would like to suggest some book titles and series that Prep boys will enjoy reading. Other titles by these authors may also be suitable. SK-3 Picture Books: some favourites Janell Cannon Verdi Chih-Yuan Chen Guji Guji Rod Clement Counting on Frank Barbara Cooney Miss Rumphius David Elliott Finn throws a fit Jules Feiffer Bark George Mem Fox Tough Boris Phoebe Gilman The balloon tree Kevin Hawkes The wicked big toddlah Simon James Baby brains Oliver Jeffers How to catch a star Lita Judge Flight School Jonathan London What newt could do for turtle Susan Meddaugh Martha speaks Peter Reynolds The dot Barbara Reid Two by two Maurice Sendak Where the wild things are David Shannon No, David! William Steig The amazing bone Melanie Watt Scaredy Squirrel Mo Willems The pigeon finds a hotdog! Jeanne Willis Troll Stinks Bethan Woollvin Little Red Beginning Independent Reading: many of these are series Tedd Arnold Fly Guy Helaine Becker Looney Bay all stars Jim Benton Lunch walks among us Adam Blade Beast quest Denys Cazet Minnie and Moo Troy Cummings The notebook of doom Tony Davis Roland Wright, future knight D.L. Green Zeke Meeks Dan Gutman My weird school Nancy Krulik Magic Bone Elizabeth S. Hunt Secret agent Jack Stalwart H.I. Larry Zac Power Megan McDonald Stink Peggy Parish Amelia Bedelia Mary Pope Osborne Magic tree house Lissa Rovetch Hot dog and Bob Cynthia Rylant Poppleton Jon Scieszka Battle Bunny Marjorie W. Sharmat Nate the great Francesca Simon Horrid Henry Geronimo Stilton Lost treasure of the emerald eye Ursula Vernon Dragonbreath Mo Willems Elephant and Piggie SK-3 Novels: for reading aloud, reading together, or reading independently Richard Atwater Mr. -

The Corrosive Impact of Transgender Ideology

The Corrosive Impact of Transgender Ideology Joanna Williams The Corrosive Impact of Transgender Ideology The Corrosive Impact of Transgender Ideology Joanna Williams First published June 2020 © Civitas 2020 55 Tufton Street London SW1P 3QL email: [email protected] All rights reserved ISBN 978-1-912581-08-5 Independence: Civitas: Institute for the Study of Civil Society is a registered educational charity (No. 1085494) and a company limited by guarantee (No. 04023541). Civitas is financed from a variety of private sources to avoid over-reliance on any single or small group of donors. All the Institute’s publications seek to further its objective of promoting the advancement of learning. The views expressed are those of the authors, not of the Institute. Typeset by Typetechnique Printed in Great Britain by 4edge Limited, Essex iv Contents Author vi Summary vii Introduction 1 1. Changing attitudes towards sex and gender 3 2. The impact of transgender ideology 17 3. Ideological capture 64 Conclusions 86 Recommendations 88 Bibliography 89 Notes 97 v Author Joanna Williams is director of the Freedom, Democracy and Victimhood Project at Civitas. Previously she taught at the University of Kent where she was Director of the Centre for the Study of Higher Education. Joanna is the author of Women vs Feminism (2017), Academic Freedom in an Age of Conformity (2016) and Consuming Higher Education, Why Learning Can’t Be Bought (2012). She co-edited Why Academic Freedom Matters (2017) and has written numerous academic journal articles and book chapters exploring the marketization of higher education, the student as consumer and education as a public good. -

2021 Panel Systems Catalog

Table of Contents Page Title Page Number Terms and Conditions 3 - 4 Specifications 5 2.0 and SB3 Panel System Options 16 - 17 Wood Finish Options 18 Standard Textile Options 19 2.0 Paneling System Fabric Panel with Wooden Top Cap 6 - 7 Fabric Posts and Wooden End Caps 8 - 9 SB3 Paneling System Fabric Panel with Wooden Top Cap 10 - 11 Fabric Posts with Wooden Top Cap 12 - 13 Wooden Posts 14 - 15 revision 1.0 - 12/2/2020 Terms and Conditions 1. Terms of Payment ∙Qualified Customers will have Net 30 days from date of order completion, and a 1% discount if paid within 10 days of the invoice date. ∙Customers lacking credentials may be required down payment or deposit in full prior to production. ∙Finance charges of 2% will be applied to each invoice past 30 days. ∙Terms of payment will apply unless modified in writing by Custom Office Design, Inc. 2. Pricing ∙All pricing is premised on product that is made available for will call to the buyer pre-assembled and unpackaged from our base of operations in Auburn, WA. ∙Prices subject to change without notice. Price lists noting latest date supersedes all previously published price lists. Pricing does not include A. Delivery, Installation, or Freight-handling charges. B. Product Packaging, or Crating charges. C. Custom Product Detail upcharge. D. Special-Order/Non-standard Laminate, Fabric, Staining and/or Labor upcharge. E. On-site service charges. F. Federal, state or local taxes. 3. Ordering A. All orders must be made in writing and accompanied with a corresponding purchase order. -

1 Women's Civic Inclusion and the Bill of Rights1 Professor Gretchen Ritter

Women’s Civic Inclusion and the Bill of Rights1 Professor Gretchen Ritter University of Texas at Austin [email protected] January 2008 (Note to “schmooze” workshop participants, University of Maryland School of Law, March 7 – 8, 2008: For a quick tour of this paper, I recommend that you read the introduction [pp.1-6], skim the section on religion [pp. 9 – 23], and read the conclusion [pp. 30-34].) Prepared for inclusion in Linda C. McClain and Joanna L. Grossman, eds., Dimensions of Women’s Equal Citizenship 1 The author wishes to thank Joanna Grossman, Gary Jacobsohn, Linda McClain, and John Robertson for their excellent comments and suggestions on this essay. 1 The Bill of Rights is often cited as foundation of the American rights conscious culture and as a central instrument in the protection and expansion of liberty and popular sovereignty in the United States. Yet, for women, the Bill of Rights has rarely played a significant role in advancing claims of civic inclusion or public citizenship. Instead, women’s rights advocates have turned primarily to the Fourteenth Amendment in their efforts to bolster women’s individual rights and civic standing under the American constitution. The failure to use the Bill of Rights as a rights claiming instrument for women comes despite the Bill’s role (as suggested by Akhil Reed Amar) in fostering civil society as well as individual rights. This essay reconsiders the problematic relationship of women’s rights advocates to the Bill of Rights and contends that the Bill has served as both an instrument for preserving gender hierarchy and a foundation for claims of public voice for women. -

On Tenncare but Still Getting Medical Bills?

Have TennCare but Still Getting Medical Bills? Many of these bills are mistakes. • OR TennCare made a mistake by not TennCare should have paid them. paying the bill. • OR TennCare decided the treatment If you don’t know why was not covered or was not medically you got a bill, it may be a necessary. mistake. • OR you missed a doctor visit. Were you on TennCare when you got the health care you were billed for? If you do get bills, here’s what to do: Then you should only get a bill IF: 1. Fill in the blanks on the • The bill is for a co-pay. A co-pay is white paper that came with your part of your doctor or hospital this brochure. Sign by the X bills. Example: You pay $5 co-pay at the bottom of the page. when you see the doctor and TennCare pays the rest. 2. Make 2 copies of the letter. 3. Send the letter to the doctor • OR you were told before being treated or hospital that billed you. that TennCare would not pay for it. You agreed to pay it. 4. Send a copy to your TennCare health plan. The name of your health plan is on • OR you lied about having TennCare or the back of your insurance card. Examples: which health plan you use. BlueCare, TennCare Select, Tennessee Behavioral Health. Write on the envelope: If you get a bill for any other Attn: Grievance Coordinator. reason, it is a mistake. Don’t pay unless they give a 5. -

Committee Approval Form

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI _____________ , 20 _____ I,______________________________________________, hereby submit this as part of the requirements for the degree of: ________________________________________________ in: ________________________________________________ It is entitled: ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ Approved by: ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ THE ORIGINS, EARLY DEVELOPMENTS AND PRESENT-DAY IMPACT OF THE JUNIOR RESERVE OFFICERS’ TRAINING CORPS ON THE AMERICAN PUBLIC SCHOOLS A dissertation submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of DOCTOR OF EDUCATION (Ed.D.) in the Department of Educational Foundations of the College of Education 2003 by Nathan Andrew Long B.M., University of Kentucky, 1996 M.Ed., University of Cincinnati, 2000 Committee Chair: Marvin J. Berlowitz, Ph.D. ABSTRACT The Junior Reserve Officers’ Training Corps (Junior ROTC) has been a part of the American educational system for nearly ninety years. Formed under the 1916 National Defense Act, its primary function was and is to train high school youth military techniques and history, citizenship and discipline. The organization has recently seen its stature elevated and its reach widened once Congress -

Report on the Draft Investigatory Powers Bill

Intelligence and Security Committee of Parliament Report on the draft Investigatory Powers Bill Chair: The Rt. Hon. Dominic Grieve QC MP Intelligence and Security Committee of Parliament Report on the draft Investigatory Powers Bill Chair: The Rt. Hon. Dominic Grieve QC MP Presented to Parliament pursuant to Section 3 of the Justice and Security Act 2013 Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed on 9 February 2016 HC 795 © Crown copyright 2016 This publication is licensed under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/version/3 or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email: [email protected]. Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. This publication is available at www.gov.uk/government/publications Any enquiries regarding this publication should be sent to us via isc.independent.gov.uk/contact Print ISBN 9781474127714 Web ISBN 9781474127721 ID 26011601 02/16 53894 19585 Printed on paper containing 75% recycled fibre content minimum Printed in the UK by the Williams Lea Group on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office THE INTELLIGENCE AND SECURITY COMMITTEE OF PARLIAMENT The Rt. Hon. Dominic Grieve QC MP (Chair) The Rt. Hon. Sir Alan Duncan KCMG MP The Rt. Hon. Fiona Mactaggart MP The Rt. Hon. George Howarth MP The Rt. Hon. Angus Robertson MP The Rt. Hon. the Lord Janvrin GCB GCVO QSO The Rt. -

The Carroll News

John Carroll University Carroll Collected The aC rroll News Student 11-3-1967 The aC rroll News- Vol. 50, No. 5 John Carroll University Follow this and additional works at: http://collected.jcu.edu/carrollnews Recommended Citation John Carroll University, "The aC rroll News- Vol. 50, No. 5" (1967). The Carroll News. 309. http://collected.jcu.edu/carrollnews/309 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Student at Carroll Collected. It has been accepted for inclusion in The aC rroll News by an authorized administrator of Carroll Collected. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GLEVltJiN~; OHiO Arts & Sciences Eisele Series The l;arroll News Testimonial Repruenting John Carroll Univeraity Page 5 Page 6 OHIO'S BEST BI-WEEKLY COLLEGE NEWSPAPER Volume L, No. 5 UNIVERSITY HEIGHTS, OHIO Nov. 3, 1967 Scabbard and Blade Military Ball 1967 Patricia Rak Donna Baldwin Noel Gay Walsh Carol Colgan 'M.oonlight ' n, Magnolias' By SANDY CERVENAK the Per s h in g Rifi!e "Stumble liam Pomp iii; c;s Jon-turf' Edito r Squad" will per for m followed by Carol Colgan, 22, from Pitts Next Saturday, Nov. 11, a demonstration in expert drilling burgh, Pa., escorted by junior Har Scabbard and Blade will pre from the Exhibition Squad. ry Sprute; sent the Eighteenth Annual This year twenty-five candidates Noel Gay Wall'h. 21, a music were nominated for the title of education major at Richmond Pro Military Ball from !) p.m. to 1 a.m. Honorary Colonel. Patrick Gnazzo, fessional Jnstitut<>, escortA•d bv sen- in t he Ca rroll gym.