Protection of the Marine Environment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1. the Monthly Monitoring Data from 86 Stations (Figure 1) Are Public Available

Reply to comments RC1: 1. The monthly monitoring data from 86 stations (Figure 1) are public available. What’s the rationale of selecting the 3 stations in the southern water of Hong Kong? Are you choosing the stations that are affected most by the nutrient-rich Pearl River plume? If so, the station on the west of SM17 and stations in the northwest of Hong Kong water (west of Lantau Island) might be more representative. Or are these stations the most productive one (based on the nutrient and chlorophyll data that are also included in this monitoring program)? Or did you find these stations experience most severe low-DO or hypoxic conditions? Reply 1: The reasons for selecting the 3 stations in the southern water of Hong Kong are as follows. Our main objective is to focus on wind effects on hypoxia and hence, we need to select stations are open to winds. Tolo Harbour where hypoxia occurs often is sheltered. The Pearl River estuary within the line of lands between Lantau Island and Macau is shallow in most areas except for deep channel and hypoxia is a rare event. Port Shelter is also sheltered. Other parts of Hong Kong waters are shallow and hypoxia hardly occurs. We have added Fig. S2 to show hypoxia occurrences in 10 water control zones in all the Hong Kong waters (Fig. S1). The 3 stations SM17, SM18 and SM19 are deep >20 m and subject to the Pearl River estuarine plume, most vulnearable to the formation of hypoxia as they have the stronger stratification in summer. -

GEO REPORT No. 282

EXPERT REPORT ON THE GEOLOGY OF THE PROPOSED GEOPARK IN HONG KONG GEO REPORT No. 282 R.J. Sewell & D.L.K. Tang GEOTECHNICAL ENGINEERING OFFICE CIVIL ENGINEERING AND DEVELOPMENT DEPARTMENT THE GOVERNMENT OF THE HONG KONG SPECIAL ADMINISTRATIVE REGION EXPERT REPORT ON THE GEOLOGY OF THE PROPOSED GEOPARK IN HONG KONG GEO REPORT No. 282 R.J. Sewell & D.L.K. Tang This report was originally produced in June 2009 as GEO Geological Report No. GR 2/2009 2 © The Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region First published, July 2013 Prepared by: Geotechnical Engineering Office, Civil Engineering and Development Department, Civil Engineering and Development Building, 101 Princess Margaret Road, Homantin, Kowloon, Hong Kong. - 3 - PREFACE In keeping with our policy of releasing information which may be of general interest to the geotechnical profession and the public, we make available selected internal reports in a series of publications termed the GEO Report series. The GEO Reports can be downloaded from the website of the Civil Engineering and Development Department (http://www.cedd.gov.hk) on the Internet. Printed copies are also available for some GEO Reports. For printed copies, a charge is made to cover the cost of printing. The Geotechnical Engineering Office also produces documents specifically for publication in print. These include guidance documents and results of comprehensive reviews. They can also be downloaded from the above website. The publications and the printed GEO Reports may be obtained from the Government’s Information Services Department. Information on how to purchase these documents is given on the second last page of this report. -

Note for Public Works Subcommittee of Finance Committee

For information PWSCI(2005-06)20 NOTE FOR PUBLIC WORKS SUBCOMMITTEE OF FINANCE COMMITTEE Supplementary information on 340DS - Port Shelter sewerage stage 3 – Sai Kung Area 4 and Mang Kung Uk sewerage INTRODUCTION In considering the paper referenced PWSC(2005-06)31 on the above project on 23 November 2005, the Public Works Subcommittee (PWSC) requested the Administration to – (a) provide supplementary information to account for any discrepancy between the computer modeling predictions in planning for the Stonecutters Island Sewage Treatment Works (SCISTW), and the actual impact of the SCISTW on the water quality of the Tsuen Wan beaches; (b) provide information on computer modeling used for assessing the impact of the sewerage and associated facilities in Sai Kung on the water quality and that adopted for the SCISTW; (c) report the E. coli level in the surrounding marine waters and beaches after the completion of the project; and (d) provide the Administration’s information paper on the project to the Sai Kung District Council (SKDC) for SKDC Members’ comments before the relevant FC meeting. THE ADMINISTRATION’S RESPONSE Comparison between Water Quality Predictions and Actual Impact for SCISTW 2. The SCISTW was built as part of the sewerage facilities under the Harbour Area Treatment Scheme (HATS) Stage 1. It is now providing chemical /treatment ..... PWSCI(2005-06)20 Page 2 treatment for 1.4 million m3/day i.e. 75% of the sewage generated from both sides of Victoria Harbour. Treated effluent is discharged via an outfall at the western harbour without disinfection. When the scheme was first introduced, water quality assessments were conducted using the “Water Quality and Hydraulic Models” (WAHMO) computer model suite in 1996. -

Waste Disposal Plan for Hong Kong Executive Summary

WASTE DISPOSAL PLAN FOR HONG KONG EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Waste Arisings Hong Kong's waste arisings currently amount to nearly 22,500 tonnes per day (t.p.d.) not including the 49,000 rrr of excavated and dredged materials which are dumped at sea. The main components of these arisings are household waste (approximately 4600 t.p.d.), industrial and commercial wastes (approximately l800 t.p.d.), construction waste (approximately 6500 t.p.d.), livestock waste (approximately 2000 t.p.d.), water works sludges (approximately 4000 t.p.d.) and pulverised fuel ash (approximately 2600 t.p.d.). Waste Collection Wastes are collected and delivered to disposal sites "by the statutory collection authorities (the Urban Council, the Regional Council and the Director of Environmental Protection), by numerous private waste collection contractors and, in the case of some industrial waste, by "in house" labour. The collection authorities collect and deliver for disposal most household, some commercial and most street wastes, some clinical waste and most excremental waste. The remainder is handled by the private sector. Environmental problems, which are generated by both the public and private sector waste collection systems, include odour, leachate spillage, dust, noise and littering. Existing controls over the operations of private sector waste collectors and transporters are fragmented and ineffective. Waste Disposal Most wastes are currently either incinerated at one of three government-operated incineration plants or disposed of at one of five government-operated landfills. The old composting plant at Chai Wan now functions as a temporary bulk transfer facility for the transport of publicly-collected waste to landfill. -

Designing Victoria Harbour: Integrating, Improving, and Facilitating Marine Activities

Designing Victoria Harbour: Integrating, Improving, and Facilitating Marine Activities By: Brian Berard, Jarrad Fallon, Santiago Lora, Alexander Muir, Eric Rosendahl, Lucas Scotta, Alexander Wong, Becky Yang CXP-1006 Designing Victoria Harbour: Integrating, Improving, and Facilitating Marine Activities An Interactive Qualifying Project Report Submitted to the Faculty of WORCESTER POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Science In cooperation with Designing Hong Kong, Ltd., Hong Kong Submitted on March 5, 2010 Sponsoring Agencies: Designing Hong Kong, Ltd. Harbour Business Forum On-Site Liaison: Paul Zimmerman, Convener of Designing Hong Kong Harbour District Submitted by: Brian Berard Eric Rosendahl Jarrad Fallon Lucas Scotta Santiago Lora Alexander Wong Alexander Muir Becky Yang Submitted to: Project Advisor: Creighton Peet, WPI Professor Project Co-advisor: Andrew Klein, WPI Assistant Professor Project Co-advisor: Kent Rissmiller, WPI Professor Abstract Victoria Harbour is one of Hong Kong‟s greatest assets; however, the balance between recreational and commercial uses of the harbour favours commercial uses. Our report, prepared for Designing Hong Kong Ltd., examines this imbalance from the marine perspective. We audited the 50km of waterfront twice and conducted interviews with major stakeholders to assess necessary improvements to land/water interfaces and to provide recommendations on improvements to the land/water interfaces with the goal of making Victoria Harbour a truly “living” harbour. ii Acknowledgements Our team would like to thank the many people that helped us over the course of this project. First, we would like to thank our sponsor, Paul Zimmerman, for his help and dedication throughout our project and for providing all of the resources and contacts that we required. -

Egn201216507825.Ps, Page 2 @ Preflight

G.N. 7825 Roads (Works, Use and Compensation) Ordinance (Chapter 370) as applied by section 26 of the Water Pollution Control (Sewerage) Regulation (Chapter 358, sub. leg.) PART OF PWP ITEM NO. 4273DS—PORT SHELTER SEWERAGE, STAGE 3, SEWERAGE AT TAI PO TSAI (Notice under section 8(2) of the Roads (Works, Use and Compensation) Ordinance as applied by section 26 of the Water Pollution Control (Sewerage) Regulation) Notice is hereby given that the Director of Environmental Protection proposes to execute the sewerage works within the limit of works area as shown on Plan No. 382770/WPCR/2.1/001 (the ‘Plan’) and described in the scheme annexed thereto, which Plan and scheme have been deposited in the Land Registry. The general nature of the proposed sewerage works is as follows:— (i) construction of about 2 900 metres of gravity sewers and associated manholes within the limit of works area as shown on the Plan; and (ii) ancillary works including temporary closure and reinstatement of carriageways, footpaths and open space. The Plan and the scheme may be inspected by members of the public, free of charge, at the following locations and during the following hours when those offices are normally open to the public:— Opening Hours Places (except on public holidays) Central and Western District Office, ⎫ ⎪ Public Enquiry Service Centre, ⎬ Monday to Friday Unit 5, Ground Floor, The Center, ⎪ 9.00 a.m.–7.00 p.m. 99 Queen’s Road Central, Hong Kong ⎭ District Lands Office, Sai Kung, ⎫ Monday to Friday 3rd Floor, Sai Kung Government Offices, ⎬ 8.45 a.m.–12.30 p.m. -

Title Heritage Preservation Other Contributor(S)University of Hong Kong Author(S) Tsang, Wai-Yee; 曾惠怡 Citation Issued Date

Title Heritage preservation Other Contributor(s) University of Hong Kong Author(s) Tsang, Wai-yee; 曾惠怡 Citation Issued Date 2009 URL http://hdl.handle.net/10722/131001 Rights Creative Commons: Attribution 3.0 Hong Kong License THE UNIVERSITY OF HONG KONG HERITAGE PRESERVATION: THE AFTER-USE OF MILITARY STRUCTURES IN HONG KONG A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF ARCHITECTURE IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF SCIENCE IN SURVEYING DEPARTMENT OF REAL ESTATE AND CONSTRUCTION BY TSANG WAI YEE HONG KONG APRIL 2009 DECLARATION I declare that this dissertation represents my own work, except where due acknowledgement is made, and that it has not been previously included in a thesis, dissertation or report submitted to this University or to any other institution for a degree, diploma or other qualification. Signed: _______________________ Named: _______________________ Date: _______________________ - i - CONTENTS LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS ......................................................................v LIST OF TABLES ......................................................................................x ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS..................................................................... xii LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS ................................................................. xiii ABSTRACT............................................................................................ xiv INTRODUCTION...................................................................................1 Research Context .................................................................................1 -

TOLO HARBOUR 史提福樓 Trackside Villas Strafford House 員工會所港鐵 峰林軒 Daisyfield

TAI PO ROAD - TAI PO KAU 東頭灣徑 策誠軒 I TOLO HARBOUR 史提福樓 Trackside Villas Strafford House 員工會所港鐵 峰林軒 Daisyfield 9 大 埔 滘 8 燕 子 里 Y 7 2 IN 叠翠豪庭 農瑞村 TSE LANE 10 1 9 吐 露 港 公 路 TAI PO KAU! Emerald 海景山莊 20 Palace 20 Seaview Villas 2 1 南苑 Southview Villas YAT YIU AVE 皇御山 The Kingston Hills 4A 逸遙路 松 苑 Tolo Ridge H U 大埔滘老圍 逍遙雋岸 N G L'Utopie L A 白鷺湖 Tai Po Kau M 互動中心 D Lo Wai 41 1 1 50 42 40 R 55 I Lake Egret V 43 E Nature Park 8 3 紅 林 路 35 60 35 44 ! 6 紅 林 居 翡翠花園 滌濤山 65 45 30 The Mangrove 8 Savanna Garden14 Constellation 大埔滘新圍 T 46 KOU LIN O K 10 Cove O 24 L 12 47 25 ! Tai Po Kau 1 19 大 埔 公 路 ─ 大 埔 滘 段 15 San Wai 蔚海山莊 8 48 20 1 10 20 5 Villa Costa 49 23 11 12 15 10 6 15 16 天賦海灣 7 10 白石角配水庫 3 荔枝坑 瞭望里 Pak Shek Kok Providence Bay 1 Ser Res 9 Lai Chi Hang 大埔滘 優 景 里 18 公園 3 墨爾文 20 21 40 19 新翠山莊 8 鹿茵山莊 Malvern 38 ! 10 FO CHUN ROAD Villa Castell 7 DeerHill Bay 7 6 海鑽 18 大 36 16 科 進 路 天賦海灣 32 24 1 10 11 溋玥 1 埔 The Graces 創新 路 9 天賦海灣 公 9 5 8 松仔園 路 22 Providence Peak ! 8 ─ 26 6 5 7 Tsung Tsai Yuen 大 YAU KING LANE 9 3 埔 II 10 逸瓏灣 100 滘 1 1 白石角海濱長廊 段 科城路 街坊婦女會 3 Mayfair by the Sea 15 L I Japanese 孫方中 5 12 3 A 泵房 1 FO CHUN ROAD R Int'l School I T 保良局 香港教育大學 1 碼頭 18 7 16 21 田家炳千禧 運動中心 E FO SHING RD 18 R 博研路 8 18 U The Education 雲滙 T 21 University 3 11 10 16 A 12 H1 A1 N of Hong Kong St Martin A2 U Sports Centre 10 7 海日灣 A 6 H9 段 K 6 鉛 O D1 The Horizon P 8 滘 I 200 嘉熙 D2 ─ A 蕉坑 道 T 5 B2 大埔滘 埔 滘 林 T 5 8 Solaria C1 Pak Shek Kok Promenade 管理站 大 A 徑 I Tsiu Hang 優 景 里 ! 3 C2 育 P East Rail Line 10 教 O 自然 CHONG SAN ROAD 埔滘 R 3 TOLO HIGHWAY1 大 O 碗窰 Wun Yiu Yiu Wun 碗窰 A -

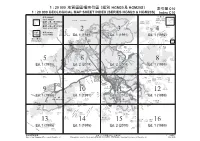

1 : 20 000 Geological Map Sheet Index (Series Hgm20

地質圖 圖 幅索引圖 (組別 及 ) 1 : 20 000 HG M 20 HG M 20S 索引圖 C10 1 : 20 000 G EOLO G IC AL M AP SHEET INDEX (SERIES H G M 20 & HG M 20S) Index C 10 大 鵬 灣 組別 HGM20S MIRS BAY 平洲 Series HGM20S 深 圳 市 SH EN ZH EN Ping C hau 沙 頭 角 吉澳海 吉澳 (Dapeng Wan) 年 T 圖 號 2 第一版 SHA TAU E 白沙洲 (1994 ) L Crooked KOK N CROOKED Island 海 I Round Island 打 鼓 嶺 HARBOUR 2 文 錦 渡 角 G Sheet Ed.1 (1994) 頭 IN MAN KAM TO TA KWU LING L 娥眉洲 沙 R A 插圖一 圖 號 6 第一版 年 羅 湖 T Crescent (2019 ) S 印洲塘 馬 草 壟 LO WU Island INSET 1 6 鹿 頸 往灣洲 Sheet Ed.1 (2019) MA TSO 上水 DOUBLE LUNG 塱 原 LUK KENG HAVEN Double 后 海 灣 SHEU NG SHU I Island L 落 馬 洲 LONG 海 I E 角 HO N VALLEY 石 湖 墟 竹 K N LOK MA 烏 蛟 騰 KO A ( 深 圳 灣 ) 黃 K H CHAU SHEK WU HU 門 C 組別 2 聯 和 墟 3 WU KAU C 4 新 田 G 赤 赤洲 Ed.1 HUI ON H HGM20 LUEN WO TANG W 大 T SAN TIN HUI R Port Islan d DEEP BAY NO (1988) Series HGM20 (Shenzhen Bay) 米 埔 粉嶺 Ed. 1 MA(I P1O 989) Ed. 1 (1991) Ed. 1 (19赤9洲口2) Ponds FAN LIN G MIDDLE CHANNEL 插圖二 版次(年份) 和 合 石 門 EL 牛 潭 尾 NN INSET 2 A 流 浮 山 WO HOP 赤 H 塔 門 NGAU SHEK C 石牛洲 TAM MEI Edition (Year) LAU FAU LO Grass Island SHAN Ponds 船 灣 O S he k N ga u T R Ch a u 天水圍 SHUEN U WAN O TIN SHU I B R WA I 海 大埔 鹽 田 仔 A 蛋 家 灣 H 錦 田 YIM TIN 灘 TAN KA TSAI 馬屎洲 G WAN 屏 山 KAM TIN 八 鄉 TA I PO 大 M a Shi Ch au N 廈 村 PAT HEUNG O PING 元朗 企 吐 露 港 L HA TSUEN SHAN F 嶺 A YUEN LO N G T 大 埔 滘 TOLO HARBOUR H T 下 O H 烏 溪 沙 M R 海 TAI PO E 十 八 鄉 石 崗 S E KAU WU KAI C O SHAP PAT HEUNG SHEK KONG SHA V 馬鞍山 十 四 鄉 E SHAP SZE 馬 料 水 M A O N HEUNG SHAN MA LIU 大 浪 大浪灣 龍 荃 錦 坳 SHUI 鼓 TSUEN KAM TAI LONG TAI LONG WAN 水 AU 火 炭 道 5 6 7 大 網 仔 8 屯門 FO TAN TAI MONG TU EN M UN TSAI Ed. -

Feasibility Study of Fishing Tourism in Hong Kong

CENTRAL POLICY UNIT THE GOVERNMENT OF THE HONG KONG SPECIAL ADMINISTRATIVE REGION FEASIBILITY STUDY OF FISHING TOURISM IN HONG KONG THE HONG KONG POLYTECHNIC UNIVERSITY JANUARY 2011 Final Report for the Feasibility Study of Fishing Tourism in Hong Kong Prepared by School of Hotel & Tourism Management The Hong Kong Polytechnic University Table of Contents Executive Summary......................................................................................................- 1 - 摘要 ................................................................................................................................- 5 - 1. Introduction...........................................................................................................- 9 - 1.1. Background.........................................................................................................- 9 - 1.2. Objectives .........................................................................................................- 10 - 1.3. Study Approach.................................................................................................- 10 - 1.4. Structure of the Report......................................................................................- 11 - 1.5. Defining Fishing Tourism .................................................................................- 11 - 1.6. Limitations ........................................................................................................- 12 - 2. Overview of Commercial Fishing and the Fishing Sector...............................- -

11 Hong Kong SAR, China 12

1 Biogeosciences 2 Research Paper 3 4 Baseline for ostracod-based northwestern Pacific and Indo-Pacific shallow- 5 marine paleoenvironmental reconstructions: ecological modeling of species 6 distributions 7 8 Yuanyuan Hong1,2,*, Moriaki Yasuhara1,2,*, Hokuto Iwatani1,2, Briony Mamo1,2 9 10 11 1School of Biological Sciences, The University of Hong Kong, Pok Fu Lam Road, 12 Hong Kong SAR, China 13 2Swire Institute of Marine Science, The University of Hong Kong, Cape d’Aguilar 14 Road, Shek O, Hong Kong SAR, China 15 16 *Corresponding authors: Hong, Y.Y. ([email protected]); Yasuhara, M. 17 ([email protected]). 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 1 26 27 28 Abstract: 29 Fossil ostracods have been widely used for Quaternary paleoenvironmental 30 reconstructions especially in marginal marine environments (e.g. for water depth, 31 temperature, salinity, oxygen levels, pollution). But our knowledge of indicator 32 species autoecology, the base of paleoenvironmental reconstructions, remains limited 33 and commonly lacks robust statistical support and comprehensive comparison with 34 environmental data. We analysed marginal marine ostracod taxa at 52 sites in Hong 35 Kong for which comprehensive environmental data are available. We applied linear 36 regression models to reveal relationships between species distribution and 37 environmental factors for 18 common taxa (mainly species, a few genera) in our 38 Hong Kong dataset, and identified indicator species of environmental parameters. For 39 example, Sinocytheridea impressa, widely distributed euryhaline species throughout 40 the East and South China Seas and the Indo-Pacific, indicates eutrophication and 41 botttom-water hypoxia. Neomonoceratina delicata, widely known species from 42 nearshore and estuarine environments in the East and South China Seas, and the Indo- 43 Pacific, indicates heavy-metal pollution and increased turbidity. -

Ancestral Images: a Hong Kong Collection

Ancestral Images A Hong Kong Collection Hugh Baker Foreword by Lady Youde (GQKXEELSOTJJOOO 63 Hong Kong University Press 14/F Hing Wai Centre 7 Tin Wan Praya Road Aberdeen Hong Kong www.hkupress.org © Hugh D.R. Baker 2011 ISBN 978-988-8083-09-1 All rights reserved. No portion of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Printed and bound by Paramount Printing Co., Ltd. in Hong Kong, China (GQKXEELSOTJJO\ 63 Contents Foreword by Lady Youde ix 19. Protection 57 Preface xi 20. Jesuits 60 1. Land 1 21. Feet 63 2. Lovers’ Rock 4 22. Funeral 66 3. Kowtow 7 23. Water 69 4. Puppets 10 24. Congratulations? 72 5. Scholar Stones 13 25. Street Trader 75 6. Daai Si 16 26. University 78 7. Customs 19 27. Ching Ming 81 8. Tree 23 28. Feast 84 9. Pigs 26 29. Pedicab 87 10. Moat 29 30. Islam 90 11. Anti-corruption 32 31. Fertility 93 12. Barrier 35 32. Lantern 96 13. Ancestral Trust 38 33. Grave 99 14. Chair 41 34. Fish 102 15. Local Government 44 35. Magic 105 16. Geomancer 47 36. Lion-heads 108 17. Duck 50 37. Incantation 111 18. Gambling 53 38. Law 114 (GQKXEELSOTJJ\ 63 vi Contents 39.