Boston Symphony Orchestra Archives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Boston Symphony Orchestra Archives

Pftft.. Slower • .. ina• alumna •••• ■■••••■•••=411• 'I 4 mp • • ••• •• Mman•IMMIln. • ■•••••■•■ ••••■••■•••■•••■■ •••• =Mr • NOW". • • =Mir • 11••■••••■••1111••••1•11• ■•111•141•111111 NUM/ 11/MIIMIN MAIMM•MIM / •• la. ••MINM/ ..MIN MI ••`' GAM MI =MO OW GM womall AMMONIUM mm,•••• ■• ".••••• rnio gradually taster 111•^ •IIMI ._./Mat MINNIP MUM OM -AM DINIIMINIMP MAIIIIIMINIMIMM•••••■ •1•1 MM. IMMIMMIIMMIO MM. MIIMMIMMO IMMIN••••••• OPP"' a tempo (lively) 111111.1. -.la a ••••••••■• • •• . • •■•■ 011•1111111MMIMINIAMmIM m••• ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ np. ••••• •••• A •• •• •••• • •• •11 OM MI MI MOM MOMMIll NI . •• maim ININIMIMMIM. ••• s4•4411•1• / a Ma . (1.• • •,41411•1~m MIHM11.11•••• 0 ■• IL • u damns. ••••■••••••••••• ••••• • •-••••,••• .ma• • ...•••■•••••••• mar- ••••• • • •••111111 • 4 . • 11.1111.1111111 Man a 4.M1 ... OM • 1■•••• ■••■=1IN•1•11••11 •IIMMIMIMMINIIIIIIMINIM-1• •••••••••••••••• NOMIM MAIM AMU MIMI MID IIIMIIIIP - IIIIIIMMIDIMIU•MIME V- • . • • 1•■•••■•••• al•IIMIMIIIII••••••••• ••••■••••••••• V M-4111•1111•111•IM • MS MI••••••■ •••• MMUMMIIMINAMMOMIIM •■•• • ••••■•• MINIam•• • • M ■•■•■ ••••••111M4•• IIIMIll. 111111.111. 511111.1111 111 ads MIIMNIM■• ■ • I 1••••••• IMAMS •111.401MMIIIIMI IIMI ■MIIIMMIMIMM • -.MMMMIMI ••• MINIMMOINNIMMIIMMMIIIMUM- ONO WM. Boston Symphony Orchestra Seiji Ozawa, Music Director Colin Davis, Principal Guest Conductor Joseph Silverstein, Assistant Conductor 16, 18, 21 October 1975 at 8:30 pm 17 October 1975 at 2:00 pm 25 November 1975 at 7:30 pm Symphony Hall, Boston Ninety-fifth season -

Charles M. Joseph. 2011. Stravinsky's Ballets. New Haven: Yale University

Charles M. Joseph. 2011. Stravinsky’s Ballets. New Haven: Yale University Press. Reviewed by Maeve Sterbenz Charles M. Joseph’s recent monograph explores an important subset of Stravinsky’s complete oeuvre, namely his works for dance. One of the aims of the book is to stress the importance of dance for Stravinsky throughout his career as a source of inspiration that at times significantly shaped his develop- ment as a composer. Joseph offers richly contextualized and detailed pictures of Stravinsky’s ballets, ones that will be extremely useful for both dance and music scholars. While he isolates each work, several themes run through Joseph’s text. Among the most important are Stravinsky’s self–positioning as simultaneously Russian and cosmopolitan; and Stravinsky’s successes in collaboration, through which he was able to create fully integrated ballets that elevated music’s traditionally subservient role in relation to choreography. To begin, Joseph introduces his motivation for the project, arguing for the necessity of an in–depth study of Stravinsky’s works for dance in light of the fact that they comprise a significant fraction of the composer’s output (more so than any other Western classical composer) and that these works, most notably The Rite of Spring, occupy such a prominent place in the Western canon. According to Joseph, owing to Stravinsky’s sensitivity to the “complexly subtle counterpoint between ballet’s interlocking elements” (xv), the ballets stand out in the genre for their highly interdisciplinary nature. In the chapters that follow, Joseph examines each of the ballets, focusing alternately on details of the works, histories of their production and reception, and their biographical contexts. -

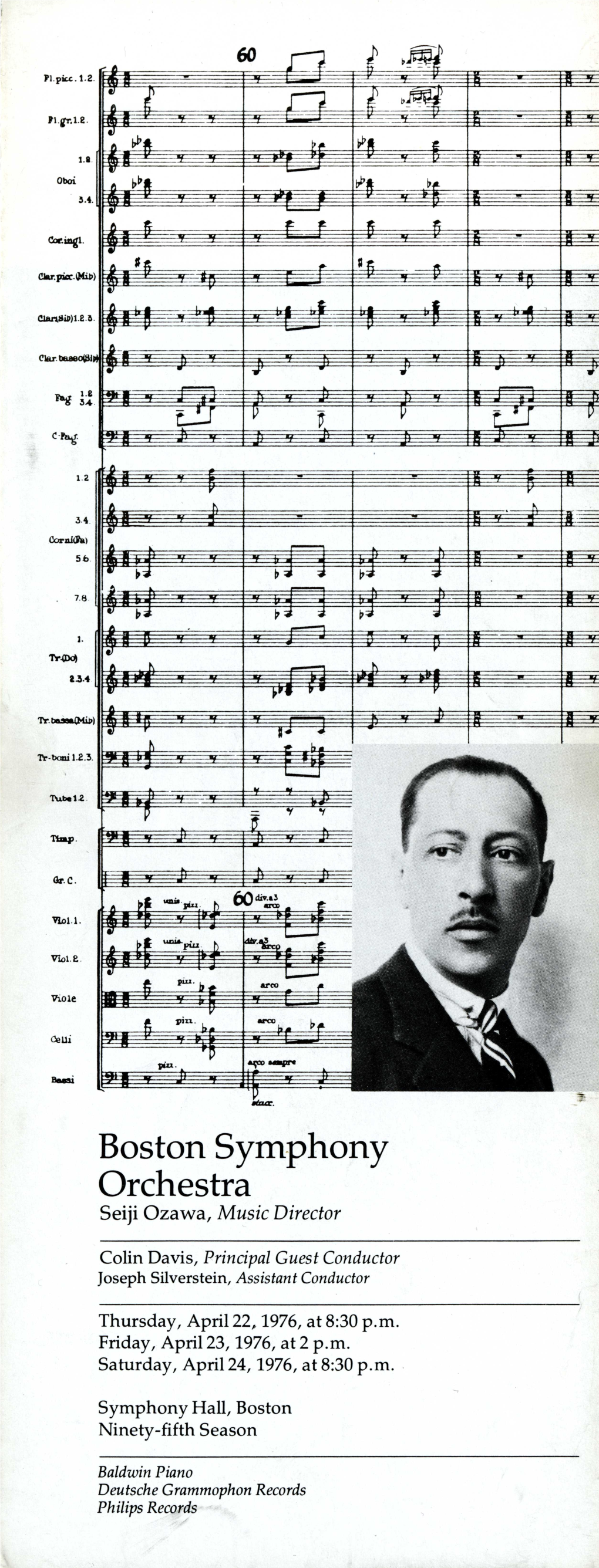

Boston Symphony Orchestra

Tangtewqpd 19 3 7-1987 BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA Seiji Ozawa, Music Director Saturday, 29 August at 8:30 The Boston Symphony Orchestra is pleased to present WYNTON MARSALIS An evening ofjazz. Week 9 Wynton Marsalis at this year's awards to win in the last four consecutive years. An exclusive CBS Masterworks and Columbia Records recording artist, Wynton made musical history at the 1984 Grammy ceremonies when he became the first instrumentalist to win awards in the categories ofjazz ("Best Soloist," for "Think of One") and classical music ("Best Soloist With Orches- tra," for "Trumpet Concertos"). He won Grammys again in both categories in 1985, for "Hot House Flowers" and his Baroque classical album. In the past four years he has received a combined total of fifteen nominations in the jazz and classical fields. His latest album, During the 1986-87 season Wynton "Marsalis Standard Time, Volume I," Marsalis set the all-time record in the represents the second complete album down beat magazine Readers' Poll with of the Wynton Marsalis Quartet—Wynton his fifth consecutive "Jazz Musician of on trumpet, pianist Marcus Roberts, the Year" award, also winning "Best Trum- bassist Bob Hurst, and drummer Jeff pet" for the same years, 1982 through "Tain" Watts. 1986. This was underscored when his The second of six sons of New Orleans album "J Mood" earned him his seventh jazz pianist Ellis Marsalis, Wynton grew career Grammy, at the February 1987 up in a musical environment. He played ceremonies, making him the only artist first trumpet in the New -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Archives

.ff Boston Symphony Orchestra Seiji Ozawa, Music Director Colin Davis, Principal Guest Conductor Joseph Silverstein, Assistant Conductor 26 November 1975 at 8:30 p.m. (Wednesday) 28 November 1975 at 2:00 p.m. 29 November 1975 at 8:30 p.m. 2, 4 December 1975 at 8:30 p.m. Symphony Hall, Boston Ninety-fifth season Baldwin Piano Deutsche Grammophon Records Program Program Notes Colin Davis conducting Felix Mendelssohn (1809-1847) Incidental Music from 'A Midsummer Night's Dream' Mendelssohn: Incidental Music from 'A Midsummer Night's Dream' The Incidental Music to Shakespeare's comedy was per- formed complete under Seiji Ozawa's direction at the 1975 I. Overture Berkshire Festival, and these excerpts were last played by II. Scherzo the Boston Symphony with Erich Leinsdorf in 1962. III. Nocturne The instrumentation calls for 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, IV. Wedding March 2 bassoons, 2 horns, 2 trumpets, tuba, timpani, cymbals, triangle and strings. Sibelius: Tapiola, Tone Poem Op. 112 Youthful miracles are seldom repeated. Mendelssohn composed his Overture to 'A Midsummer Night's Dream' Intermission at seventeen (1826), with a miraculous deftness and deli- cacy, an elfin imagination and humor then unmatched. Yet, near the end of his life (1843), Mendelssohn did match the Sibelius: Symphony No. 6 Op. 104 miracle. He was invited by the King of Prussia to compose incidental music for a Berlin production of Ein Sommernachts- I. Allegro molto moderato traum. His youthful enthusiasm for Shakespeare surged II. Allegretto moderato back. With the most felicitous ease he wove the early III. Poco vivace themes into new pieces and ideas flowed with the Roman- Allegro molto N. -

22 by Gretchen Horlacher a Fundamental Issue in the Analysis Of

Sketches and Superimposition in Stravinsky’s Symphony of Psalms by Gretchen Horlacher A fundamental issue in the analysis of Stravinsky’s music is to describe how the composer juxtaposes and superimposes repeating motivic fragments. Do layered ostinati spin out in opposition to one another or do they interact? Does the progress of one affect the progress of another? Do they create for- mal relationships beyond their own repetitions? Evidence in sketches for works spanning the Russian period through the early serial work Agon (1953–57) suggests that this issue was a primary concern for the composer: many sketches and drafts are dedicated to working out the relationships be- tween and among simultaneously sounding strata so that they jointly shape passages of music. These documents share a common working method. Early in the composi- tional process, Stravinsky seems often to have drafted short “phrases” where the constituent motivic fragments are placed in relationship but repeated only briefly or not at all; subsequent drafts expand the lengths of phrases by in- serting repetitions of existing material into the original phrases.1 Such a pro- cedure allows us to compare the longer (and most often retained) versions with their shorter predecessors, giving us insight both into how Stravinsky develops his material and what might constitute a complete formal unit. In other words, we can trace the expansions of phrases through interpolation in order to identify how later versions have a more continuous formal shape and fit more easily into larger formal units. Consider as an example two sketches for a passage from the third move- ment of the Symphony of Psalms (1929–30); the two sketches are reproduced as Examples 1a and 1b and the final score is reproduced as Example 2.2 A pre- liminary description of the passage might go as follows. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 97, 1977-1978

97th SEASON . TRUST BANKING. A symphony in financial planning. Conducted by Boston Safe Deposit and Trust Company Decisions which affect personal financial goals are often best made in concert with a professional advisor However, some situations require consultation with a number of professionals skilled in different areas of financial management. Real estate advisors. Tax consultants. Estate planners. Investment managers. To assist people with these needs, our venerable Boston banking institution has developed a new banking concept which integrates all of these professional services into a single program. The program is called trust banking. Orchestrated by Roger Dane, Vice President, 722-7022, for a modest fee. DIRECTORS Hans H. Estin George W. Phillips C. Vincent Vappi Vernon R. Alden Vice Chairman, North Executive Vice President, Vappi & Chairman, Executive American Management President Company, Inc. Committee Corporation George Putnam JepthaH. Wade Nathan H. Garrick, Jr. Partner, Choate, Hall Dwight L. Allison, Jr. Chairman, Putnam of the Chairman of the Board Vice Chairman Management & Stewart Board David C. Crockett Company, Inc. William W.Wolbach Donald Hurley Deputv to the Chairman J. John E. Rogerson Vice Chairman Partner, of the Board of Trustees Goodwin, Partner, Hutchins & of the Board Procter Hoar and to the General & Wheeler Honorary Director Director, Massachusetts Robert Mainer Henry E. Russell Sidney R. Rabb General Hospital Senior Vice President, President Chairman, The Stop & The Boston Company, Inc. F. Stanton Deland, Jr. Mrs. George L. Sargent Shop Companies, Partner, Sherburne, Inc. Director of Various Powers & Needham William F. Morton Corporations Director of Various Charles W. Schmidt Corporations President, S.D. Warren Lovett C. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 91, 1971

FRIDAY -SATURDAY 17 NINETY-FIRST SEASON 1971-1972 ADIVARI created for all time a perfect marriage of precision and beauty for both the eye and the ear. He had the unique genius to combine a thorough knowledge of the acoustical values of wood with a fine artist's sense of the good and the beautiful. Unexcelled by anything before or after, his violins have such purity of tone, they are said to speak with the voice of a lovely soul within. In business, as in the arts, experience and ability are invaluable. We suggest you take advantage of our extensive insurance background by letting us review your needs either business or personal and counsel you to an intelligent program. We respectfully invite your inquiry. CHARLES H. WATKINS & CO., INC. Richard P. Nyquist, President Charles G. Carleton, Vice President 147 Milk Street Boston, Massachusetts 02109 542-1250 OBRION, RUSSELL & CO. Insurance of Every Description BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA WILLIAM STEINBERG Music Director MICHAEL TILSON THOMAS Associate Conductor NINETY-FIRST SEASON 1971-1972 THE TRUSTEES OF THE BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA INC. TALCOTT M. BANKS President FRANCIS W. HATCH PHILIP K. ALLEN Vice-President HAROLD D. HODGKINSON ROBERT H. GARDINER Vice-President E. MORTON JENNINGS JR JOHN L THORNDIKE Treasurer EDWARD M. KENNEDY ALLEN G. BARRY HENRY A. LAUGHLIN ERWIN D. CANHAM EDWARD G. MURRAY RICHARD P. CHAPMAN JOHN T. NOONAN ABRAM T. COLLIER MRS JAMES H. PERKINS MRS HARRIS FAHNESTOCK IRVING W. RABB THEODORE P. FERRIS PAUL C. REARDON SIDNEY STONEMAN TRUSTEES EMERITUS HENRY B. CABOT PALFREY PERKINS EDWARD A. TAFT ADMINISTRATION OF THE BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA THOMAS D. -

STRAVINSKY the Firebird

557500 bk Firebird US 14/01/2005 12:19pm Page 8 Philharmonia Orchestra STRAVINSKY The Philharmonia Orchestra, continuing under the renowned German maestro Christoph von Dohnanyi as Principal Conductor, has consolidated its central position in British musical life, not only in London, where it is Resident Orchestra at the Royal Festival Hall, but also through regional residencies in Bedford, Leicester and Basingstoke, The Firebird and more recently Bristol. In recent seasons the orchestra has not only won several major awards but also received (Complete original version) unanimous critical acclaim for its innovative programming policy and commitment to new music. Established in 1945 primarily for recordings, the Philharmonia Orchestra went on to attract some of this century’s greatest conductors, such as Furtwängler, Richard Strauss, Toscanini, Cantelli and von Karajan. Otto Klemperer was the Petrushka first of many outstanding Principal Conductors throughout the orchestra’s history, including Maazel, Muti, (Revised 1947 version) Sinopoli, Giulini, Davis, Ashkenazy and Salonen. As the world’s most recorded symphony orchestra with well over a thousand releases to its credit, the Philharmonia Orchestra also plays a prominent rôle as one of the United Kingdom’s most energetic musical ambassadors, touring extensively in addition to prestigious residencies in Paris, Philharmonia Orchestra Athens and New York. The Philharmonia Orchestra’s unparalleled international reputation continues to attract the cream of Europe’s talented young players to its ranks. This, combined with its brilliant roster of conductors and Robert Craft soloists, and the unique warmth of sound and vitality it brings to a vast range of repertoire, ensures performances of outstanding calibre greeted by the highest critical praise. -

The University of Chicago an Experience-Oriented

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO AN EXPERIENCE-ORIENTED APPROACH TO ANALYZING STRAVINSKY’S NEOCLASSICISM A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DIVISION OF THE HUMANITIES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC BY SARAH MARIE IKER CHICAGO, ILLINOIS AUGUST 2017 CONTENTS List of Figures ...................................................................................................................................... iv List of Tables ..................................................................................................................................... viii Acknowledgments ............................................................................................................................... ix Abstract .................................................................................................................................................. x Introduction: Analysis, Experience, and Experience-Oriented Analysis ..................................... 1 1 Neoclassicism, Analysis, and Experience ................................................................................ 10 1.1 Neoclassicism After the Great War ................................................................................. 10 1.2 Analyzing Neoclassicism: Problems and Solutions ....................................................... 18 1.3 Whence Listener Experience? ........................................................................................... 37 1.4 The Problem of Historicism ............................................................................................ -

The Firebird

EDUCATION Education RESOURCE THE WITH PAQUITA SUPPORTED BY NATIONAL TOURING SUPPORTING EDUCATION CHOREOGRAPHER VAL CANIPAROLI PARTNER rnzb.org.nz facebook.com/nzballet CONTENTS Curriculum links 3 The Firebird 4 The characters 4 The story 5 The creatives 7 Q&A with Loughlan Prior 12 The history of The Firebird 14 Dance activities 16 Crafts and puzzles 18 What to do at a ballet 22 Ballet timeline 23 THE FIREBIRD 29 JULY – 2 SEPTEMBER 2021 2 CURRICULUM LINKS In this unit you and your students will: WORKSHOP LEARNING • Learn about the elements that come OBJECTIVES FOR together to create a theatrical ballet LEVELS 3 & 4 experience. Level 3 students will learn how to: • Identify the processes involved in Develop practical knowledge making a theatre production. • Use the dance elements to develop and share their personal movement vocabulary. CURRICULUM LINKS IN Develop ideas THIS UNIT • Select and combine dance elements in response to a variety of stimuli. Values Communicate and interpret Students will be encouraged to value: • Prepare and share dance movement • Innovation, inquiry and curiosity, individually and in pairs or groups. by thinking critically, creatively and • Use the elements of dance to describe dance reflectively. movements and respond to dances from a • Diversity, as found in our different cultures variety of cultures. and heritages. • Community and participation for the Level 4 students will learn how to: common good. Develop practical knowledge • Apply the dance elements to extend personal KEY COMPETENCIES movement skills and vocabularies and to explore the vocabularies of others. • Using language, symbols and text – Develop ideas Students will recognise how choices of • Combine and contrast the dance elements to language and symbols in live theatre affect express images, ideas, and feelings in dance, people’s understanding and the ways in using a variety of choreographic processes. -

Mengjiao Yan Phd Thesis.Pdf

The University of Sheffield Stravinsky’s piano works from three distinct periods: aspects of performance and latitude of interpretation Mengjiao Yan A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Music The University of Sheffield Jessop Building, Sheffield, S3 7RD, UK September 2019 1 Abstract This research project focuses on the piano works of Igor Stravinsky. This performance- orientated approach and analysis aims to offer useful insights into how to interpret and make informed decisions regarding his piano music. The focus is on three piano works: Piano Sonata in F-Sharp Minor (1904), Serenade in A (1925), Movements for Piano and Orchestra (1958–59). It identifies the key factors which influenced his works and his compositional process. The aims are to provide an informed approach to his piano works, which are generally considered difficult and challenging pieces to perform convincingly. In this way, it is possible to offer insights which could help performers fully understand his works and apply this knowledge to performance. The study also explores aspects of latitude in interpreting his works and how to approach the notated scores. The methods used in the study include document analysis, analysis of music score, recording and interview data. The interview participants were carefully selected professional pianists who are considered experts in their field and, therefore, authorities on Stravinsky's piano works. The findings of the results reveal the complex and multi-faceted nature of Stravinsky’s piano music. The research highlights both the intrinsic differences in the stylistic features of the three pieces, as well as similarities and differences regarding Stravinsky’s compositional approach. -

The Late Choral Works of Igor Stravinsky

THE LATE CHORAL WORKS OF IGOR STRAVINSKY: A RECEPTION HISTORY _________________________________________________________ A Thesis presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School at the University of Missouri-Columbia ________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts ____________________________ by RUSTY DALE ELDER Dr. Michael Budds, Thesis Supervisor DECEMBER 2008 The undersigned, as appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have examined the thesis entitled THE LATE CHORAL WORKS OF IGOR STRAVINSKY: A RECEPTION HISTORY presented by Rusty Dale Elder, a candidate for the degree of Master of Arts, and hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. _________________________________________ Professor Michael Budds ________________________________________ Professor Judith Mabary _______________________________________ Professor Timothy Langen ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my deepest gratitude to each member of the faculty who participated in the creation of this thesis. First and foremost, I wish to recognize the ex- traordinary contribution of Dr. Michael Budds: without his expertise, patience, and en- couragement this study would not have been possible. Also critical to this thesis was Dr. Judith Mabary, whose insightful questions and keen editorial skills greatly improved my text. I also wish to thank Professor Timothy Langen for his thoughtful observations and support. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS……………………………………………………………...ii ABSTRACT……………………………………………………………………………...v CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION: THE PROBLEM OF STRAVINSKY’S LATE WORKS…....1 Methodology The Nature of Relevant Literature 2. “A BAD BOY ALL THE WAY”: STRAVINSKY’S SECOND COMPOSITIONAL CRISIS……………………………………………………....31 3. AFTER THE BOMB: IN MEMORIAM DYLAN THOMAS………………………45 4. “MURDER IN THE CATHEDRAL”: CANTICUM SACRUM AD HONOREM SANCTI MARCI NOMINIS………………………………………………………...60 5.