Evaluating Urban Resilience to Climate Change: a Multi-Sector Approach

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Umass Medical School

University of Massachusetts Medical School Hazard Mitigation Plan 41 Shattuck Road Andover, MA 01810 800-426-4262 226110.00 UMass Medical woodardcurran.com August 2014 COMMITMENT & INTEGRITY DRIVE RESULTS DRAFT TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION PAGE NO. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .....................................................................................................................................ES-1 1. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................................ 1-1 1.1 Plan Description ................................................................................................................................ 1-1 1.2 Plan Authority and Purpose ............................................................................................................... 1-2 1.3 University of Massachusetts System Description ............................................................................... 1-3 1.3.1 University of Massachusetts Medical School Overview ...................................................................... 1-3 1.3.1.1 Campus Relationship with UMass Memorial Medical Center ......................................... 1-5 1.3.1.2 Campus History ............................................................................................................ 1-5 1.3.1.3 City of Worcester, MA................................................................................................... 1-6 1.3.1.4 Campus Location & Environment ................................................................................. -

Investigating the Interpretation of the Storm Prediction Center’S Convective Outlook by Broadcast Meteorologists and the Us Public

UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE COLORFUL LANGUAGE: INVESTIGATING THE INTERPRETATION OF THE STORM PREDICTION CENTER’S CONVECTIVE OUTLOOK BY BROADCAST METEOROLOGISTS AND THE US PUBLIC A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE IN METEOROLOGY By SEAN R. ERNST Norman, Oklahoma 2020 COLORFUL LANGUAGE: INVESTIGATING THE INTERPRETATION OF THE STORM PREDICTION CENTER’S CONVECTIVE OUTLOOK BY BROADCAST METEOROLOGISTS AND THE US PUBLIC A THESIS APPROVED FOR THE SCHOOL OF METEOROLOGY BY THE COMMITTEE CONSISTING OF Dr. Harold Brooks, Chair Dr. Elinor Martin Dr. Scott Salesky Dr. Naoko Sakaeda Dr. Joseph Ripberger Dr. Kodi Berry © Copyright by SEAN R. ERNST 2020 All Rights Reserved. Acknowledgements I would first like to thank my lead advisors, Dr. Joe Ripberger and Dr. Harold Brooks, for providing me guidance, opportunity, and funding to perform this research, without them I would not have been able to perform any of the research presented in this paper. I would also like to thank Dr. Kodi Berry and Holly Obermeier, who welcomed me into their CTA broadcaster study with open arms and helped me organize and record interviews with broadcasters from across the nation. As part of that effort, I would like to thank Joseph Trujillo and Emma Landeros for assisting with note-taking and moderation during the focus group and CTA interviews, both helped me keep track of all the information flying around so that I could focus on grilling the broadcasters! I’d be remiss without thanking Dr. Patrick Marsh for his assistance in outlining the development of the 5-tier SPC outlook and for encouraging my work on this project, having the ability to share my results and learn about future SPC product development was invaluable to this project. -

Raymond P. Harold Collection

WORCESTER HISTORICAL MUSEUM 30 Elm Street Worcester, Massachusetts ARCHIVES 2006.10 Raymond P. Harold Collection Processd by Christopher Lewis July 2011 1 T A B L E O F C O N T E N T S S e r i e s S u b - s e r i e s Page Box Collection Information 3 Historical/Biographical Notes 4 Scope and Content 4 Series Description 5 Miscellaneous Photographs 6 I,OVS, ovs Vol. I, ovs Vol. 2, SPR OVS Isaiah Thomas Award - Photographs Photo Album 1, Photo A l b u m 2 Plaques/Awards/Recognitions 10 1,2, OVS, SPR OVS, A l b u m 1 Tornado of 1953 - Photographs 15 Photo Album 3 Objects-See Curator 2 Collection Information Abstract: Raymond P. Harold Collection Finding Aid : Finding Aid in print form is available in the Repository. Preferred Citation : Worcester Historical Museum, Worcester, Massachusetts. Provenance: Donated by Ruth Zollinger in 2006, daughter of Raymond P. Harold. MARC Access : Collection is cataloged in MARC under the following subject headings 3 Historical/Biographical Notes Raymond P. Harold (1898-1972) has been regarded as one of the most influential figures in Woreester's history. His business was "with the wage earner who saves money and buys a home." With that philosophy, he revolutionized thrift banking in Central Massachusetts. He was the ehairman and chief executive officer of First Federal Savings and Loan Association. The institution had resources of more than $400 million. Mr. Harold was chiefly responsible for the development of public housing and urban renewal in Worcester after WWII. -

2005 State-Owned Land Valuation by Marilyn H

A Publication of the Department of Revenue’s Division of Local Services Cityand Alan LeBovidge Commissioner Gerard D. Perry Deputy Commissioner Town Volume 18, No. 4 April 2005 2005 State-Owned Land Valuation by Marilyn H. Browne The Commissioner of Revenue deter- cepted street lists and valued the prop- tional mail of its availability. This data mines the fair cash value of certain erties without input from the local asses- was put forth for assessors to reconcile state-owned lands (SOL) pursuant to sors. It was clear after the 2000 SOL their data with ours to eliminate uncer- M.G.L. Ch. 58 Secs. 13–17 and Ch. 59 valuation that many local assessors tainties about what land is eligible for Sec. 5G. Cities and towns are reim- did not know what land in their com- reimbursement in advance of the 2005 bursed for loss of local tax revenue on munities was reimbursable. We believe SOL valuation. In a letter dated Febru- the Cherry Sheet’s Payment-in-Lieu-of- that was due to the fact that assessors ary 27, 2004, communities were in- Tax, or by MWRA through the Depart- change frequently, non-taxable proper- formed that the Water Supply Protec- ment of Conservation and Recreation’s ties are not typically where assessors tion Land data (Ch. 59 Sec. 5G), was Division of Water Supply Protection invest their time and scarce resources posted to the Internet and they were (formerly MDC Watershed Land). and because BLA, not assessors, val- expected to have it reconciled by June ued the reimbursable SOL land. -

Charlton, Charlton City and Charlton Depot Vol

Mailed free to requesting homes in Charlton, Charlton City and Charlton Depot Vol. V, No. 26 PROUD MEDIA SPONSOR OF RELAY FOR LIFE OF THE GREATER SOUTHBRIDGE AREA! COMPLIMENTARY HOME DELIVERY ONLINE: WWW.CHARLTONVILLAGER.COM Friday, July 1, 2011 Regional dive team completes boat training BY AMANDA COLLINS VILLAGER STAFF WRITER CHARLTON — The District 7 cen- tral area regional dive team com- pleted boat rescue training June 20 at Buffumville Lake. The regional dive team, which is made up of 28 police and fire offi- cials from five area towns — Auburn, Charlton, Oxford, Sturbridge and Southbridge — was created last year, when the towns came together to form the unit because each couldn’t financially sustain one on their own. “We decided to come together so that instead of each town having a couple divers, we could pool our resources and make it easier,” said Don Contois, the Auburn team leader. The team is critical because of the area’s landscape, said Charlton Fire Department Chief Charles Cloutier. FOR YOUR He noted that within the five towns the team serves there are “at least 57 Courtesy photo HEALTH large lakes and ponds and two rivers In boat rescue diving, divers crawl along running at a swift rate.” the bottom of bodies of water attached Amanda Collins photos The team meets six times per year to boat by rope. to train and practice responding to a “It’s different, there’s a lot to CHARLTON — A health fair was variety of water emergencies. This learn,” said Cloutier. “Instead of held Friday, June 24, at the Charlton latest training was the regional working off the shore — where you Senior Center, and attendees were team’s first experience using a plat- given the chance to consult with area form boat and boat diving. -

June 30, 2009 Annual Report

Massachusetts Historical SocietyAnnual Report July 1, 2008, to June 30, 2009 Board of Trustees 2009 Officers Life Trustees Ms. Amalie M. Kass, Chair Mr. Leo L. Beranek Mr. William R. Cotter, Vice Chair Mr. Henry Lee Mr. John F. Moffitt, Secretary Trustees Emeriti Mr. William C. Clendaniel, Treasurer Ms. Nancy R. Coolidge Trustees Mr. James M. Storey Ms. Nancy S. Anthony Mr. John L. Thorndike Prof. Bernard Bailyn The Hon. Levin H. Campbell Mr. Arthur C. Hodges Prof. Pauline Maier Ms. Catherine S. Menand Ms. Sheila D. Perry Mr. Frederick G. Pfannenstiehl Ms. Lia G. Poorvu Mr. William L. Saltonstall † Mr. L. Dennis Shapiro Mr. Joseph Peter Spang Mr. Michael R. Yogg The Hon. Hiller B. Zobel Contents A Message from the Chair of the Board and the President 1 July 1, 2008, to June 30, 2009: The Year in Review Collections 3 Research Activities and Services 5 Programming and Outreach 8 Development and Membership 11 Treasurer’s Report 13 Fellows, Corresponding Members, and Honorary Fellows 15 Memorials 19 Gifts 24 Library Accessions 29 Fellowship Recipients 3 1 Scholarly and Public Programs 33 Annual Report of the Massachusetts Historical Society 1154 Boylston Streeet, Boston, Massachsuetts, 02215 617-646-0500 • www.masshist.org A Message from the Chair of the Board & the President This year, the Massachusetts Historical Society made great strides in pursuit of its mission while adjusting to evolving economic realities. Thanks to a dedicated and talented staff and a faithful and energized Board of Trustees, we were able to trim our budget while still accomplishing a wide array of projects, despite reduced staff resources; and an increase in fundraising made it possible to place our operations on a stable financial footing. -

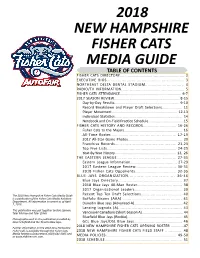

Fisher Cats 2018 Media Guide 2018 Final Unofficial.Indd

2018 NEW HAMPSHIRE FISHER CATS MEDIA GUIDE TABLE OF CONTENTS FISHER CATS DIRECTORY....................................................... 2 EXECUTIVE BIOS.............................................................. 3 NORTHEAST DELTA DENTAL STADIUM............................... 4 RADIO/TV INFORMATION..................................................... 5 FISHER CATS ATTENDANCE............................................................. 6-7 2017 SEASON REVIEW............................................................. 8-15 Day-by-Day Results............................................................. 9-10 Record Breakdown and Player Draft Selections................... 11 Player Movement................................................................ 12-13 Individual Sta s cs................................................................ 14 Notebook and On-Field Prac ce Schedule................................... 15 FISHER CATS HISTORY AND RECORDS............................ 16-26 Fisher Cats to the Majors........................................................... 16 All-Time Roster...................................................... 17-19 2017 All-Star Game Photos.................................................... 20 Franchise Records.................................................... 21-23 Top Five Lists.......................................................... 24-25 Year-By-Year History.............................................................. 13, 26 THE EASTERN LEAGUE................................................. 27-35 -

Worcester Natural History Society, Records, 1825-1970 Mss. Boxes W Mss

AMERICAN ANTIQUARIAN SOCIETY MANUSCRIPT COLLECTIONS NAME OF COLLECTION: LOCATION(S): Worcester Natural History Society, Records, 1825-1970 Mss. boxes W Mss. octavo vols. W Mss. folio vols. W Mss. oversize vols. W Mss. oversize boxes W SIZE OF COLLECTION: 7 manuscript boxes; 138 octavo volumes; 27 folio volumes; 3 oversize volumes; 1 oversize folder SOURCES OF INFORMATION ON COLLECTION: SOURCE OF COLLECTION: Gifts of the Worcester Natural History Society, May 1931 and November 1932, Octavo Volume #3 gift of Eugene L. Schwab, October 1948, additional donation from the Worcester EcoTarium, February 2015. COLLECTION DESCRIPTION: The Worcester Natural History Society was first formed in 1825 as the Worcester Lyceum of Natural History and united with the Worcester Lyceum in November 1829. The Society has been known by various names throughout its history: Worcester Lyceum of Natural History (1825), Worcester Lyceum (1829), Worcester County Lyceum and Library Association (185), Worcester Lyceum and Natural History Association (1866), Worcester Natural History Society (1884), the Worcester Science Museum (1960), the New England Science Center (1986), and, currently, the Worcester EcoTarium (1998). The general aim of the organization was to promote the knowledge and investigation of natural history. Its activities included a series of lectures, the establishment of a circulating library, and the sponsorship of debates. In 1882 the Society opened its natural history museum to the public and from 1885 to 1893 it ran a natural history summer camp on Lake Quinsigamond. The boys’ camp featured both day and overnight options, and consisted of various outdoor activities, field excursions, and military-style physical fitness training, as well as lectures taught by Society faculty. -

The 1953 Worcester Tornado in Its Time: Panic and Recovery” Historical Journal of Massachusetts Volume 36, No

Lianne Lajoie, “The 1953 Worcester Tornado in its Time: Panic and Recovery” Historical Journal of Massachusetts Volume 36, No. 2 (Summer 2008). Published by: Institute for Massachusetts Studies and Westfield State University You may use content in this archive for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the Historical Journal of Massachusetts regarding any further use of this work: [email protected] Funding for digitization of issues was provided through a generous grant from MassHumanities. Some digitized versions of the articles have been reformatted from their original, published appearance. When citing, please give the original print source (volume/ number/ date) but add "retrieved from HJM's online archive at http://www.westfield.ma.edu/mhj. The Worcester Tornado in Its Time: Panic and Recovery By Lianne Lajoie The city of Worcester, Massachusetts is located in central Massachusetts. Today, experts are aware that the city is part of New England’s severe weather corridor. In fact, Worcester County is regarded as the most tornado-prone region of the northeastern United States.1 However, this fact was unknown in the 1950s. This paper explores the violent tornado that devastated Worcester, Massachusetts and surrounding towns in 1953. By looking at the aftermath and the rebuilding of the city, this paper will explain how the Worcester Tornado was unique to the 1950s, in terms of both human response and existing technology. In his work Acts of God: The Unnatural History of Natural Disasters in America, environmental historian Ted Steinberg looks at the history of tornadoes and other natural disasters in America. Steinberg believes that the amount of death and destruction caused by natural disasters is influenced by socioeconomic factors and that some of America’s worst natural disasters were made more damaging through poor economic decision-making. -

Project Number RP-FOWA

Project Number RP-FOWA THE FUTURE OF THE WORCESTER MEMORIAL AUDITORIUM An Interactive Qualifying Project Report submitted to the Faculty of the WORCESTER POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Science by Misael Diaz &Ha Hoang Date: April, 13 2009 Professor Roberto Pietroforte Major Advisor Professor John Wilkes Co-Advisor Abstract: The Worcester Memorial Auditorium, built after a long political struggle as a war memorial for the use and benefit of the people, has recently fallen into disuse. This Interactive Qualifying Project investigates the circumstances surrounding the planning, useful life, and decline of the Auditorium through an examination of available historical records. The original functional intention of the Auditorium, the actual resulting use during its successful lifetime, and the reasons surrounding its decline are analyzed herein. Additionally, the national and regional economic forces influencing the City of Worcester, and specifically the life of the Auditorium, are examined through statistical records and historical texts. With this information it is possible to conduct an unbiased critical analysis of any proposal for future use of the Auditorium. ii Table of Contents Chapter………………………………………………………………………………………..Page Abstract: .......................................................................................................................................... ii Table of Contents .......................................................................................................................... -

Evaluating the Public's Perception of Urban Trees

WORCESTER POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE Evaluating the Public’s Perception of Urban Trees: The case of Greendale and Burncoat Neighborhoods of Worcester, Massachusetts Value Trees An Interactive Qualifying Project Report Submitted to the Faculty of the WORCESTER POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Science Jeffrey Robinson, Kyle Diaz, Jeffrey Li with Gretchen Folk 12/17/2009 Environmental, economic, social, and health-related benefits associated with urban trees. This study focused on the trees in the Greendale and Burncoat neighborhoods of Worcester, Massachusetts that were infested and eventually removed as a result of the Asian Longhorn Beetle. This project explores the public perception of urban trees in Worcester, Massachusetts. The team employed the use of four data collection methods including a content analysis, questionnaires, focus groups, and Q-methodology to gather data on the economic, Introduction This study is phase-one of a multi-phase research project aimed at better understanding how the public values trees. Phase-one, completed from August – December 2009, examined the Greendale and Burncoat neighborhoods of Worcester, Massachusetts; an area that recently lost over 25,000 trees in a two-mile radius as a result of the 2008 ice storm and the Asian longhorn beetle infestation. Phase-two will probe the opinions of residents in the quarantined zone who have not lost their trees. Phase-three will further explore neighborhoods outside the quarantine zone. In phase-one, the research team explored how residents in the Greendale and Burncoat neighborhoods of Worcester, Massachusetts value the trees in their neighborhoods. Four data collection methods were employed in these neighborhoods including: two focus groups with residents, twenty-five questionnaires with residents, a content analysis on the Worcester Telegram and Gazette, and lastly, q-sorts with residents. -

2005 Baseball MG.P65

200520052005 20052005 HolyHoly CrossCross BBaseballaseball ScheduleSchedule MARCH 06 Sun. vs. Nebraska-Omaha Bradenton, Fla. 09 Sat. vs. Navy * Fitton Field 2 pm 07 Mon. vs. Georgetown Bradenton, Fla. 10 Sun. vs. Navy * Fitton Field 12:00 pm 07 Mon. vs. Connecticut Bradenton, Fla. 10 Sun. vs. Navy * Fitton Field 2 pm HolyHolyHoly CrossCrossCross BBBaseballaseballaseball 08 Tue. vs. Georgetown Bradenton, Fla. 13 Wed. vs. Hartford Simsbury, Conn. 3 pm 10 Thu. vs. Bowling Green Bradenton, Fla. 14 Thu. vs. Quinnipiac Hamden, Conn. 3 pm 11 Fri. vs. Sacred Heart Bradenton, Fla. 16 Sat vs. Lehigh * Fitton Field 12:00 pm 12 Sat. vs. Central Michigan Bradenton, Fla. 16 Sat. vs. Lehigh * Fitton Field 2 pm 19 Sat. vs. CCSU New Britain, Conn. 17 Sun. vs. Lehigh * Fitton Field 12:00 pm 19 Sat. vs. CCSU New Britain, Conn. 17 Sun. vs. Lehigh * Fitton Field 2 pm 20 Sun. vs. CCSU New Britain, Conn. 20 Wed. vs. Dartmouth Fitton Field 3 pm 22 Tue. vs. Clark Worcester, Mass. 23 Sat. vs. Army * West Point, N.Y. 12:00 pm 23 Wed vs. Bentley Fitton Field 23 Sat. vs. Army * West Point, N.Y. 2 pm 26 Sat. vs. Northeastern Brookline, Mass. 24 Sun. vs. Army * West Point, N.Y. 12:00 pm 26 Sat. vs. Northeastern Brookline, Mass. 24 Sun. vs. Army * West Point, N.Y. 2 pm 29 Tue vs. Siena Fitton Field 27 Wed. vs. Maine Sanford, Maine 3:30 pm 30 Wed. vs. Boston College Chestnut Hill, Mass. 30 Sat. vs. Bucknell * Fitton Field 12:00 pm 30 Sat.