Ten Perfections: a Study Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Post-Canonical Buddhist Political Thought

Post-Canonical Buddhist Political Thought: Explaining the Republican Transformation (D02) (conference draft; please do not quote without permission) Matthew J. Moore Associate Professor Dept. of Political Science Cal Poly State University 1 Grand Avenue San Luis Obispo, CA 93407 805-756-2895 [email protected] 1 Introduction In other recent work I have looked at whether normative political theorizing can be found in the texts of Early or Canonical Buddhism, especially the Nikāya collections and the Vinaya texts governing monastic life, since those texts are viewed as authentic and authoritative by all modern sects of Buddhism.1 In this paper I turn to investigate Buddhist normative political theorizing after the early or Canonical period, which (following Collins2 and Bechert3) I treat as beginning during the life of the Buddha (c. sixth-fifth centuries BCE) and ending in the first century BCE, when the Canonical texts were first written down. At first glance this task is impossibly large, as even by the end of the early period Buddhism had already divided into several sects and had begun to develop substantial regional differences. Over the next 2,000 years Buddhism divided into three main sects: Theravada, Mahāyāna, and Vajrayāna. It also developed into numerous local variants as it mixed with various national cultures and evolved under different historical circumstances. To give just one example, the Sri Lankan national epic, the Mahāvaṃsa, is central to Sinhalese Buddhists’ understanding of what Buddhism says about politics and very influential on other Southeast Asian versions of Buddhism, but has no obvious relevance to Buddhists in Tibet or Japan, who in turn have their own texts and traditions. -

Introduction to Tibetan Buddhism, Revised Edition

REVISED EDITION John Powers ITTB_Interior 9/20/07 2:23 PM Page 1 Introduction to Tibetan Buddhism ITTB_Interior 9/20/07 2:23 PM Page 2 ITTB_Interior 9/20/07 2:23 PM Page 3 Introduction to Tibetan Buddhism revised edition by John Powers Snow Lion Publications ithaca, new york • boulder, colorado ITTB_Interior 9/20/07 2:23 PM Page 4 Snow Lion Publications P.O. Box 6483 • Ithaca, NY 14851 USA (607) 273-8519 • www.snowlionpub.com © 1995, 2007 by John Powers All rights reserved. First edition 1995 Second edition 2007 No portion of this book may be reproduced by any means without prior written permission from the publisher. Printed in Canada on acid-free recycled paper. Designed and typeset by Gopa & Ted2, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Powers, John, 1957- Introduction to Tibetan Buddhism / by John Powers. — Rev. ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and indexes. ISBN-13: 978-1-55939-282-2 (alk. paper) ISBN-10: 1-55939-282-7 (alk. paper) 1. Buddhism—China—Tibet. 2. Tibet (China)—Religion. I. Title. BQ7604.P69 2007 294.3’923—dc22 2007019309 ITTB_Interior 9/20/07 2:23 PM Page 5 Table of Contents Preface 11 Technical Note 17 Introduction 21 Part One: The Indian Background 1. Buddhism in India 31 The Buddha 31 The Buddha’s Life and Lives 34 Epilogue 56 2. Some Important Buddhist Doctrines 63 Cyclic Existence 63 Appearance and Reality 71 3. Meditation 81 The Role of Meditation in Indian and Tibetan Buddhism 81 Stabilizing and Analytical Meditation 85 The Five Buddhist Paths 91 4. -

Curriculum Vitae of Jay L Garfield

Curriculum Vitae of Jay L Garfield Present Appointment Doris Silbert Professor in the Humanities and Professor of Philosophy, Smith College Director, Five Colleges Tibetan Studies in India Program Director, Logic Program Professor, Graduate Faculty of Philosophy, University of Massachusetts Professor of Philosophy, University of Melbourne Adjunct Professor of Philosophy, Central Institute of Higher Tibetan Studies Collaborateur Scientifique, Université de Lausanne Contact Details Address: Department of Philosophy Smith College Northampton, MA 01063 USA Phone: +1 413 585 3649 Fax: +1 413 585 3710 Secretary: +1 413 585 3642 E-mail: [email protected] Phone (India) +91 98399 00490 Phone (Australia) +614 1063 8965 Personal Details Date of Birth: November 13, 1955 Marital Status: Married, four children Citizenship: USA, Australia Home Address: 105 January Hills Road Amherst, MA 01002 Home Phone +1 413 548 9577 Education A.B., Oberlin College, 1975 MA, University of Pittsburgh, 1976 PhD, University of Pittsburgh, 1986 Areas of Professional Interest Philosophy of Psychology, Cognitive Science, Philosophy of Mind, Philosophy of Language, Metaphysics, Epistemology, Buddhist Philosophy, Applied and Theoretical Ethics, Philosophy of Technology, Artificial Intelligence, Hermeneutics June 2008 Curriculum vitae of Prof Jay L Garfield page 2 Academic Honours Phi Beta Kappa Sigma Xi High Honours in Philosophy, Oberlin College High Honours in Psychology, Oberlin College Andrew Mellon Predoctoral Fellow in Philosophy, 1975-1976 Teaching Fellow in Philosophy, 1976-1980 Michael Bennett Memorial Philosophical Essay Prize, 1980 Fellow of the Academy of Finland, 1986-1987 Grants and Fellowships National Endowment for Humanities Summer Institute Fellowship (Nagarjuna), 1989 Fulbright Teaching/Research Grant, Sri Lanka 1990-1991 (declined) Indo-American Fellow, 1990-1991 Hewlett-Mellon Research Grants, 1993, 1994 (India) Culpepper Languages Across the Curriculum Grant 1994-1995. -

Buddhist " Protestantism" in Poland

Occasional Papers on Religion in Eastern Europe Volume 13 Issue 2 Article 5 4-1993 Buddhist " Protestantism" in Poland Malgorzata Alblamowicz-Borri University of Paris Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/ree Part of the Christianity Commons, and the Eastern European Studies Commons Recommended Citation Alblamowicz-Borri, Malgorzata (1993) "Buddhist " Protestantism" in Poland," Occasional Papers on Religion in Eastern Europe: Vol. 13 : Iss. 2 , Article 5. Available at: https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/ree/vol13/iss2/5 This Article, Exploration, or Report is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ George Fox University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Occasional Papers on Religion in Eastern Europe by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ George Fox University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BUDDHIST "PROTESTANTISM" IN POLAND by Malgorzata Ablamowicz - Borri Malgorzata Ablamowicz - Borri (Buddhist) received a master's degree at Universite de Paris X. This article is an resumme of her thesis.1 She also presented this topic at the UNESCO at the Tenth Congress of Buddhist Studies iti Paris, July 18-21, 1991. Currently she lives in Santa Barbara, California. I. Phases of Assimilation of Buddhism in the Occident I propose to divide the assimilation of Buddhism in the Occident into three phases: 1. The first phase was essentially intellectual; Buddhist texts were translated and submitted to philosophical analysis. In Poland, this phase appeared after World War I when Poland gained independence. Under the leadership of Andrzej Gawronski, Stanislaw Schayer, Stanislaw Stasiak, Arnold Kunst, Jan Jaworski and others, the Polish tradition of Buddhist studies formed mainly in two study centers, Lwow (now in Ukraine) and Warsaw. -

American Buddhists: Enlightenment and Encounter

CHAPTER FO U R American Buddhists: Enlightenment and Encounter ★ he Buddha’s Birthday is celebrated for weeks on end in Los Angeles. TMore than three hundred Buddhist temples sit in this great city fac- ing the Pacific, and every weekend for most of the month of May the Buddha’s Birthday is observed somewhere, by some group—the Viet- namese at a community college in Orange County, the Japanese at their temples in central Los Angeles, the pan-Buddhist Sangha Council at a Korean temple in downtown L.A. My introduction to the Buddha’s Birthday observance was at Hsi Lai Temple in Hacienda Heights, just east of Los Angeles. It is said to be the largest Buddhist temple in the Western hemisphere, built by Chinese Buddhists hailing originally from Taiwan and advocating a progressive Humanistic Buddhism dedicated to the pos- itive transformation of the world. In an upscale Los Angeles suburb with its malls, doughnut shops, and gas stations, I was about to pull over and ask for directions when the road curved up a hill, and suddenly there it was— an opulent red and gold cluster of sloping tile rooftops like a radiant vision from another world, completely dominating the vista. The ornamental gateway read “International Buddhist Progress Society,” the name under which the temple is incorporated, and I gazed up in amazement. This was in 1991, and I had never seen anything like it in America. The entrance took me first into the Bodhisattva Hall of gilded images and rich lacquerwork, where five of the great bodhisattvas of the Mahayana Buddhist tradition receive the prayers of the faithful. -

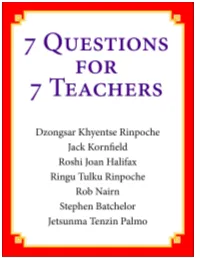

7 Questions for 7 Teachers

7 Questions for 7 Teachers On the adaptation of Buddhism to the West and beyond. Seven Buddhist teachers from around the world were asked seven questions on the challenges that Buddhism faces, with its origins in different Asian countries, in being more accessible to the West and beyond. Read their responses. Dzongsar Khyentse Rinpoche, Jack Kornfield, Roshi Joan Halifax, Ringu Tulku Rinpoche, Rob Nairn, Stephen Batchelor, Jetsunma Tenzin Palmo Introductory note This book started because I was beginning to question the effectiveness of the Buddhism I was practising. I had been following the advice of my teachers dutifully and trying to find my way, and actually not a lot was happening. I was reluctantly coming to the conclusion that Buddhism as I encountered it might not be serving me well. While my exposure was mainly through Tibetan Buddhism, a few hours on the internet revealed that questions around the appropriateness of traditional eastern approaches has been an issue for Westerners in all Buddhist traditions, and debates around this topic have been ongoing for at least the past two decades – most proactively in North America. Yet it seemed that in many places little had changed. While I still had deep respect for the fundamental beauty and validity of Buddhism, it just didn’t seem formulated in a way that could help me – a person with a family, job, car, and mortgage – very effectively. And it seemed that this experience was fairly widespread. My exposure to other practitioners strengthened my concerns because any sort of substantial settling of the mind mostly just wasn’t happening. -

RASCEE and Their Activity ”

Laudere, Marika. 2013. “Introduction to Buddhism in Contemporary Lithuania: Groups RASCEE and Their Activity ”. Religion and Society in Central and Eastern Europe 6 (1): 21-32. Introduction to Buddhism in Contemporary Lithuania: Groups and Their Activity Marika Laudere, Daugavpils University, Latvia ABSTRACT: New religious ideas have gained considerable momentum in Post- Soviet countries in the wake of the collapse of the USSR. People have started to become more involved in religious groups that were not previously active in these regions. Lithuania is no exception. This study is based on fieldwork in Buddhist groups (2012-2013) and attempts to document the development of Buddhism in Lithuania by investigating several Buddhist groups and their activities in contemporary Lithuania. KEYWORDS: Buddhism, group, activity, practice, religion. Introduction During the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, knowledge of Buddhist teaching became available to larger numbers of people via a gradual spreading to new areas of the world, particularly to the West. Initially, the existence of Buddhism in the West was largely related to the activities of migrant Asian Buddhists. However, starting from the beginning of the second-half of the twentieth century, Buddhism has aroused interest in Westerners themselves (Wallace 2002, 34). Buddhist attitudes towards peace, mindfulness and care for all living creatures appear to be close to the view of life of those Westerners who have started to put this knowledge into practice. Western attraction to Buddhism represents a surge in the popularity of spirituality rather than a return of religion, with Buddhist spirituality offering a credible response to the anxieties of the modern world (Faure 2009, 139). -

Allowing Spontaneity: Practice, Theory, and Ethical Cultivation in Longchenpa's Great Perfection Philosophy of Action

Allowing Spontaneity: Practice, Theory, and Ethical Cultivation in Longchenpa's Great Perfection Philosophy of Action The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:40050138 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Allowing Spontaneity: Practice, Theory, and Ethical Cultivation in Longchenpa’s Great Perfection Philosophy of Action A dissertation presented by Adam S. Lobel to The Committee on the Study of Religion in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of The Study of Religion Harvard University Cambridge, MA April 2018! ! © 2018, Adam S. Lobel All rights reserved $$!! Advisor: Janet Gyatso Author: Adam S. Lobel Allowing Spontaneity: Practice, Theory, and Ethical Cultivation in Longchenpa’s Great Perfection Philosophy of Action Abstract This is a study of the philosophy of practical action in the Great Perfection poetry and spiritual exercises of the fourteenth century Tibetan author, Longchen Rabjampa Drime Ozer (klong chen rab 'byams pa dri med 'od zer 1308-1364). I inquire into his claim that practices may be completely spontaneous, uncaused, and effortless and what this claim might reveal about the conditions of possibility for action. Although I am interested in how Longchenpa understands spontaneous practices, I also question whether the very categories of practice and theory are useful for interpreting his writings. -

Buddhism, Mindfulness, and Transformative Politics

NEW POLITICAL SCIENCE, 2016 VOL. 38, NO.2, 272- 282 http://dx.dol.org/1 0.1080/07393148.2016.11S319S Buddhism, Mindfulness, and Transformative Politics Matthew J. Moore Department of Political Science, California Polytechnic State University, San Luis Obispo, USA ABSTRACT This article examines whether the American cultural phenomena of the practice of Buddhism or the Buddhism-derived technique of mindfulness are likely to be helpful to the political left. It summarizes the central teachings of the ancient Buddhist texts, with particular focus on the issues of mindfulness and politics. It also reviews the political history of Buddhist countries. The author argues that although modern Buddhism has shed its historical embrace of absolutist monarchy in favor of republicanism, and although there is some ideological overlap between Buddhism and the American Left, Buddhism in America is too small a movement for it to be of much significance for progressive politics. Mindfulness appears to be capable of becoming a much larger phenomenon, but its separation from its Buddhist origins makes it also unlikely to be strategically important for the Left. Introduction Siddhattha Gotama, also known as the Buddha, 1 developed the practice of mindfulness (sat/) in the sixth-fifth centuries see as a central part of his spiritual teachings, which have subsequently developed into the religion/philosophy known as Buddhism. Today, Buddhism has some four hundred to five hundred million adherents worldwide, making it the fourth or fifth largest contemporary religion.3 As in the Vedic religion from which it developed (and which itself evolved into modern Hinduism), in Buddhism the central goal is to escape the cycle of birth-death-rebirth known as safTisora by both working through the kamma 4 (in Pali ; Sanskrit: karma) accumulated from previous incarnations and by learning not to CONTACT Matthew J. -

Nationalist Ethnicities As Religious Identities: Islam, Buddhism, and Citizenship in Myanmar Imtiyaz Yusuf

ajiss34-4-noconfrep_ajiss 11/3/2017 9:31 AM Page 100 Forum Nationalist Ethnicities as Religious Identities: Islam, Buddhism, and Citizenship in Myanmar Imtiyaz Yusuf Preliminary Statement: An Overview of Muslim-Buddhist Relations For centuries, the Rohingya have been living within the borders of the coun - try established in 1948 as Burma/Myanmar. Today left stateless, having been gradually stripped of their citizenship rights, they are described by the United Nations as one of the most persecuted minorities in the world. In order to understand the complexity of this conflict, one must consider how Burma is politically transitioning from military to democratic rule, a process that is open (much as was Afghanistan) to competition for resources by in - ternational and regional players such as the United States, China, India, Is - rael, Japan, and Australia. 1 To be fair, the record of Southeast Asian Muslim countries with Buddhist minorities is also not outstanding. Buddhist minori - ties identified as ethnic groups have faced great discrimination in, among others, Bangladesh, Malaysia, Indonesia, and Brunei. 2 Imtiyaz Yusuf is the director of the Center for Buddhist-Muslim Understanding, College of Religious Studies, Mahidol University, Salaya, Thailand. His recent publications are A Plane - tary and Global Ethics for Climate Change and Sustainable Energy (2016); “Muslim-Buddhist Relations Caught between Nalanda and Pattani,” in Ethnicity and Conflict in Buddhist Societies in South and Southeast Asia , ed. K.M. de Silva (2015) and “Islam and Buddhism,” in Wiley- Blackwell Companion to Interreligious Dialogue , ed. Catherine Cornille (2013). In addition to being a contributor to the Oxford Encyclopedia of Islamic World (2009), the Oxford Dictionary of Islam (2003), the Encyclopedia of Qur’an (2002), and the Oxford Encyclopedia of Modern Islamic World (1995), he was also the special editor of The Muslim World: A Special Issue on Islam and Buddhism 100, nos. -

Buddhist Nuns' Ordination in the Tibetan Canon

Buddhist Nuns’ Ordination in the Tibetan Canon Online Bibliography in Connection with the DFG Project compiled by Carola Roloff and Birte Plutat Part I: Author List February 2021 gefördert durch Gleichstellungsfonds des Asien-Afrika-Instituts der Universität Hamburg Nuns‘ Ordination in Buddhism – Bibliography. Part 1: Author / Title list February 2021 Abeysekara, Ananda (1999): Politics of Higher Ordination, Buddhist Monastic Identity, and Leadership in Sri Lanka. In Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies 22 (2), pp. 255–280. Abeysekara, Ananda (2002): Colors of the Robe. Religion, Identity, and Difference. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press. Adams, Vincanne; Dovchin, Dashima (2000): Women's Health in Tibetan Medicine and Tibet's "First" Female Doctor. In Ellison Banks Findly (Ed.): Women’s Buddhism, Buddhism’s Women. Tradition, Revision, Renewal. Boston: Wisdom Publications, pp. 433–450. Agrawala, V. S. (1966): Some Obscure Words in the Divyāvadāna. In Journal of the American Oriental Society 86 (2), pp. 67–75. Alatekara, Anata Sadāśiva; Radhakrishnan, Sarvepalli (Eds.) (1957): Felicitation Volume Presented to Professor Sripad Krishna Belvalkar. Banaras: Motilal Banarsidass. Ali, Daud (1998): Technologies of the Self. Courtly Artifice and Monastic Discipline in Early India. In Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient (Journal d'Histoire Economique et Sociale de l'Orient) 41 (2), pp. 159–184. Ali, Daud (2000): From Nāyikā to Bhakta. A Genealogy of Female Subjectivity in Early Medieval India. In Julia Leslie, Mary McGee (Eds.): Invented Identities. The Interplay of Gender, Religion, and Politics in India. New Delhi, New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 157–180. Ali, Daud (2003): Gardens in Early Indian Court Life. -

Abstracts Pp. 152-450

Kingship Ideology in Sino-Tibetan Diplomacy during the VII-IX centuries Emanuela Garatti In this paper I would like to approach the question of the btsan-po’s figure and his role in the international exchanges like embassies, peace agreements and matrimonial alliances concluded between the Tibetan and the Tang during the Tibetan Empire. In order to do that, I examine some passages of Tibetan and Chinese sources. Tibetan ancient documents, like PT 1287, the PT 1288, the IOL Tib j 750 and the text of the Sino-Tibetan treaty of 821/822. For the Chinese sources I used the encyclopaedia Cefu yuangui which has never been extensively used in the study of the Tibetan ancient history. Concerning the embassies one can see that they are dispatched with important gifts when the btsan-po want to present a request. Those are registered as tribute (ch. chaogong) by the Chinese authors but one can assume, analysing the dates of embassies that the Tibetan emissaries are sent to the court with presents only when they had to present a specific request from the Tibetan emperor. Moreover, the btsan-po is willing to accept the diplomatic codes but refuses all attempt of submission from the Chinese authorities like the “fish-bag” (ch. yudai) proposed to the Tibetan ambassadors as a normal gift. For the treaties, the texts of these agreements show the evolution of the position of the btsan-po towards the Chinese court and the international diplomacy: the firsts pacts see the dominant position of Tang court over the btsan-po’s delegation.