Appendix 2 Civilian Wartime Experience in The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lx1/Rtetcanjviuseum

lx1/rtetcanJViuseum PUBLISHED BY THE AMERICAN MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY CENTRAL PARK WEST AT 79TH STREET, NEW YORK 24, N.Y. NUMBER 1707 FEBRUARY 1 9, 1955 Notes on the Birds of Northern Melanesia. 31 Passeres BY ERNST MAYR The present paper continues the revisions of birds from northern Melanesia and is devoted to the Order Passeres. The literature on the birds of this area is excessively scattered, and one of the functions of this review paper is to provide bibliographic references to recent litera- ture of the various species, in order to make it more readily available to new students. Another object of this paper, as of the previous install- ments of this series, is to indicate intraspecific trends of geographic varia- tion in the Bismarck Archipelago and the Solomon Islands and to state for each species from where it colonized northern Melanesia. Such in- formation is recorded in preparation of an eventual zoogeographic and evolutionary analysis of the bird fauna of the area. For those who are interested in specific islands, the following re- gional bibliography (covering only the more recent literature) may be of interest: BISMARCK ARCHIPELAGO Reichenow, 1899, Mitt. Zool. Mus. Berlin, vol. 1, pp. 1-106; Meyer, 1936, Die Vogel des Bismarckarchipel, Vunapope, New Britain, 55 pp. ADMIRALTY ISLANDS: Rothschild and Hartert, 1914, Novitates Zool., vol. 21, pp. 281-298; Ripley, 1947, Jour. Washington Acad. Sci., vol. 37, pp. 98-102. ST. MATTHIAS: Hartert, 1924, Novitates Zool., vol. 31, pp. 261-278. RoOK ISLAND: Rothschild and Hartert, 1914, Novitates Zool., vol. 21, pp. 207- 218. -

What I Did and What I Saw

NEW GUINEA WHAT I DID AND WHAT I SAW Barry Craig, 2018 [email protected] Photos copyright B. Craig unless otherwise attributed I guess I was destined to be a walker from an early age ̶ I may have got that from my father. Boot camp, c.1941 Martin Place, Sydney, c.1941 Because my father fought at Sattelberg in the hills west of Finschhafen in 1943, I became fascinated by New Guinea and read avidly. After studying anthropology at the University of Sydney I went to PNG as an Education Officer in 1962. I asked to be posted to Telefomin. Languages of Central New Guinea I lived at Telefomin 1962-65. In 1963-64, Bryan Cranstone, British Museum, was based at Tifalmin west of Telefomin to research and collect items of material culture. His method of documenting things that he collected drew my attention to the house boards and shields of the region. He became my mentor. I was fortunate to witness the last of the male initiation ceremonies – dakasalban candidates with sponsor at left, otban at right. In 1964, I collected about 320 items of material culture for the Australian Museum, supported with photographs, and began a survey of all house boards and shields in the wider region, extended in 1967. This resulted in a Masters Thesis in 1969 and a booklet in 1988. At Bolovip, the board photographed by Champion in 1926 (left) was still there in 1967 (top right) but had been discarded by 1981. Map of 1967 survey Interior photo showing shields, pig jawbones, a sacred feather-bag and ancestral skulls and long-bones. -

Peter G. Sack Land Between Two Laws

This book penetrates the facade Peter G. Sack Land Between of colonial law to consider European land acquisitions Two Laws in the context of a complex historical process. Its context is land, but it is fundamentally a legal study of the problems arising out of the dichotomy between traditional New Early European Land Guinea law and imposed Prussian law. Though these Acquisitions in New Guinea problems arose out of events that took place more than fifty years ago, they are of immediate relevance for New Guinea in the 1970s. They are mostly still unsolved and are only now emerging from under the layers of po litical compromise that have concealed them. Dr Sack emphasises the differences between tra ditional and introduced law in New Guinea in order to in vestigate the chances of a synthesis between them. He offers no panacea, but points up clearly the tasks which must be accomplished before the 'land between two laws' can become a truly indepen dent state. This is an essential work for anthropologists, lawyers and all those con cerned with the emergence of a stable, unified Papua New Guinea. This book penetrates the facade Peter G. Sack Land Between of colonial law to consider European land acquisitions Two Laws in the context of a complex historical process. Its context is land, but it is fundamentally a legal study of the problems arising out of the dichotomy between traditional New Early European Land Guinea law and imposed Prussian law. Though these Acquisitions in New Guinea problems arose out of events that took place more than fifty years ago, they are of immediate relevance for New Guinea in the 1970s. -

Capture Section Report of Tuna Fisheries Development East New

i South Pacific Commission Coastal Fisheries Programme CAPTURE SECTION REPORT OF TUNA FISHERIES DEVELOPMENT EAST NEW BRITAIN, PAPUA NEW GUINEA PHASE I FAD DEPLOYMENT PROJECT 15 NOVEMBER 1992 – 31 MAY 1993 PHASE II PILOT TUNA LONGLINE PROJECT 1 JUNE 1993 – 15 SEPTEMBER 1994 by S. Beverly Consultant Masterfisherman and L. Chapman Fisheries Development Adviser © Copyright South Pacific Commission 1996 The South Pacific Commission authorises the reproduction of this material, whole or in part, in any form, provided that appropriate acknowledgement is given. Original text: English South Pacific Commission cataloguing-in-publication data Beverly, S Capture section report of tuna fisheries development assistance East New Britain, Papua New Guinea / by S. Beverly and L. Chapman 1. Fisheries—Equipment and supplies 2. Fish aggregation device— Papua New Guinea. FAD I. Title II. South Pacific Commission 639.2'9585 AACR2 ISBN 982-203-511-X Prepared for publication and printed at South Pacific Commission headquarters Noumea, New Caledonia, 1996 ii SUMMARY The waters of Papua New Guinea, including the archipelagic waters of the New Guinea Islands Region, harbour a rich tuna resource that has not been exploited commercially by longline vessels for almost a decade. In the latter part of 1991, Government and private-sector interests in the New Guinea Islands Region began exploring the possibility of establishing a domestic tuna longline industry. As part of this effort the PNG Islands Region Secretariat and the East New Britain (ENB) Provincial Government sought the assistance of staff from the South Pacific Commission’s Coastal Fisheries Programme to design a tuna fisheries development strategy, and to secure the technical and financial assistance necessary to initiate such a programme. -

Guide to the Fayette W. Clifford World War II Collection

Grems-Doolittle Library Schenectady County Historical Society 32 Washington Ave., Schenectady, NY 12305 (518) 374-0263 [email protected] Guide to the Fayette W. Clifford World War II Collection Creator: Clifford, Fayette W., 1917 – 1984 Accession Number: 2019.18 Extent: 0.42 linear feet (1 full-size document box containing 20 folders) Source: Military belongings of Fayette W. Clifford of Schenectady Inclusive Dates: 1943 – 1960 Bulk Dates: 1944 - 1946 Access: Access to materials in this collection is unrestricted. Abstract: The Fayette W. Clifford World War II collection consists materials from the military career of Fayette W. Clifford. Catalog Terms: Clifford, Fayette W., 1917 – 1984 Clifford, Fayette, 1917 – 1984 World War II Scope and Content Note: The Fayette W. Clifford World War II collection consists largely of small- and medium-sized photographs taken during Clifford’s military service in the Philippines. Additional items include typed letters, citations and certificates; newspaper clippings; army publications; handwritten manuscript pages; and a few small artifacts. The collection also includes an assortment of military patches and pins, but because these are in the care of the Schenectady County Historical Society museum rather than the archives they are not included in this finding aid. Biographical Note: Fayette W. Clifford was born in 1917 in Schenectady, NY to John V. Clifford and his wife Annette E. Clifford. After graduating from Nott Terrace High School he found employment as a production clerk for General Electric. In September of 1943 he joined the service and began basic training at Camp Blanding, FL, as a Private First Class in the 126th Regiment of the famed 32nd Infantry Division. -

The Final Campaigns: Bougainville 1944-1945

University of Wollongong Thesis Collections University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Year The final campaigns: Bougainville 1944-1945 Karl James University of Wollongong James, Karl, The final campaigns: Bougainville 1944-1945, PhD thesis, School of History and Politics, University of Wollongong, 2005. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/467 This paper is posted at Research Online. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/467 The Final Campaigns: Bougainville 1944-1945 A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree Doctor of Philosophy from University of Wollongong by Karl James, BA (Hons) School of History and Politics 2005 i CERTIFICATION I, Karl James, declare that this thesis, submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of Doctor of Philosophy, in the School of History and Politics, University of Wollongong, is wholly my work unless otherwise referenced or acknowledged. The document has not been submitted for qualifications at any other academic institution. Karl James 20 July 2005 ii Table of Contents Maps, List of Illustrations iv Abbreviations vi Conversion viii Abstract ix Acknowledgments xi Introduction 1 1 ‘We have got to play our part in it’. Australia’s land war until 1944. 15 2 ‘History written is history preserved’. History’s treatment of the Final Campaigns. 30 3 ‘Once the soldier had gone to war he looked for leadership’. The men of the II Australian Corps. 51 4 ‘Away to the north of Queensland, On the tropic shores of hell, Stand grimfaced men who watch and wait, For a future none can tell’. The campaign takes shape: Torokina and the Outer Islands. -

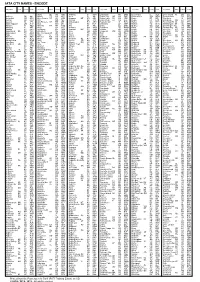

Iata City Names - Encode

IATA CITY NAMES - ENCODE City name State Country Code City name State Country Code City name State Country Code City name State Country Code City name State Country Code City name State Country Code Alpha QL AU ABH Aribinda BF XAR Bakelalan MY BKM Beersheba IL BEV Block Island RI US BID Aalborg DK AAL Alpine TX US ALE Arica CL ARI Baker City OR US BKE Befandriana MG WBD Bloemfontein ZA BFN Aalesund NO AES Alroy Downs NT AU AYD Aripuana MT BR AIR Baker Lake NU CA YBK Beica ET BEI Blonduos IS BLO Aarhus DK AAR Alta NO ALF Arkalyk KZ AYK Bakersfield CA US BFL Beida LY LAQ Bloodvein MB CA YDV Aasiaat GL JEG Alta Floresta MT BR AFL Arkhangelsk RU ARH Bakkafjordur IS BJD Beihai CN BHY Bloomfield Ri QL AU BFC Aba/Hongyuan CN AHJ Altai MN LTI Arlit NE RLT Bakouma CF BMF Beihan YE BHN Bloomington IN US BMG Abadan IR ABD Altamira PA BR ATM Arly BF ARL Baku AZ BAK Beijing CN BJS Bloomington-NIL US BMI Abaiang KI ABF Altay CN AAT Armenia CO AXM Balakovo RU BWO Beira MZ BEW Blubber Bay BC CA XBB Abakan XU ABA Altenburg DE AOC Armidale NS AU ARM Balalae SB BAS Beirut LB BEY Blue Bell PA US BBX Abbotsford BC CA YXX Altenrhein CH ACH Arno MH AMR Balgo Hill WA AU BQW Bejaia DZ BJA Bluefield WV US BLF Abbottabad PK AAW Alto Rio Seng CB AR ARR Aroa PG AOA Bali CM BLC Bekily MG OVA Bluefields NI BEF Abbs YE EAB Alton IL US ALN Arona SB RNA Bali PG BAJ Belaga MY BLG Blumenau SC BR BNU Abeche TD AEH Altoona PA US AOO Arorae KI AIS Balikesir TR BZI Belem PA BR BEL Blythe CA US BLH Abemama KI AEA Altus OK US LTS Arrabury QL AU AAB Balikpapan ID BPN Belfast GB -

B Military Service Report

West Seneca Answers the Call to Arms Residents in World War II Town of West Seneca, New York Name: BABULSKI JOSEPH C. Address: Service Branch:ARMY - AIR FORCE Rank: CPL Unit / Squadron: 93RD AIRDROME SQUADRON Medals / Citations: ASIATIC-PACIFIC CAMPAIGN RIBBON 2 BATTLE STARS WORLD WAR II VICTORY MEDAL AMERICAN CAMPAIGN MEDAL ARMY AIR FORCES TECHNICIAN AP MECHANIC BADGE GOOD CONDUCT MEDAL Theater of Operations / Assignment: PACIFIC THEATER Service Notes: Corporal Joseph Babulski was stationed in Australia and saw action during the battles for New Guinea and Luzon in the Philippines, earning Corporal Babulski 3 Battle Stars Base Assignments: Miscelleaneous: Airdrome Squadrons were designed to provide the minimum number of personnel to run an air base for a limited time / Aviation Engineers would prepare a landing ground, then an Airdrome Squadron would start it running until a combat group, station complement squadron, service squadron, and/or various Army - Air Force units arrived to operate the base The Army Air Forces Technician AP Mechanic Badge was a badge of the United States Army Air Forces awarded to denote special training and qualifications held by the members of the Army Air Force The Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Ribbon (Medal) was a military awarded to any member of the United States Military who served in the Pacific Theater from 1941 to 1945 Battle (Combat) Stars were presented to military personnel who were engaged in specific battles in combat under circumstances involving grave danger of death or serious bodily injury from enemy action The American Campaign Medal/Ribbon (also known as the (ATO) American Theater of Operations Ribbon) was a military award of the United States Armed Forces which was first created on November 6, 1942 by President 2014 WWW.WSVET.ORG West Seneca Answers the Call to Arms Residents in World War II Town of West Seneca, New York Franklin D. -

'Feed the Troops on Victory': a Study of the Australian

‘FEED THE TROOPS ON VICTORY’: A STUDY OF THE AUSTRALIAN CORPS AND ITS OPERATIONS DURING AUGUST AND SEPTEMBER 1918. RICHARD MONTAGU STOBO Thesis prepared in requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Humanities and Social Sciences University of New South Wales, Canberra June 2020 Thesis/Dissertation Sheet Surname/Family Name : Stobo Given Name/s : Richard Montagu Abbreviation for degree as given in the : PhD University calendar Faculty : History School : Humanities and Social Sciences ‘Feed the Troops on Victory’: A Study of the Australian Corps Thesis Title : and its Operations During August and September 1918. Abstract 350 words maximum: (PLEASE TYPE) This thesis examines reasons for the success of the Australian Corps in August and September 1918, its final two months in the line on the Western Front. For more than a century, the Corps’ achievements during that time have been used to reinforce a cherished belief in national military exceptionalism by highlighting the exploits and extraordinary fighting ability of the Australian infantrymen, and the modern progressive tactical approach of their native-born commander, Lieutenant-General Sir John Monash. This study re-evaluates the Corps’ performance by examining it at a more comprehensive and granular operational level than has hitherto been the case. What emerges is a complex picture of impressive battlefield success despite significant internal difficulties that stemmed from the particularly strenuous nature of the advance and a desperate shortage of manpower. These played out in chronic levels of exhaustion, absenteeism and ill-discipline within the ranks, and threatened to undermine the Corps’ combat capability. In order to reconcile this paradox, the thesis locates the Corps’ performance within the wider context of the British army and its operational organisation in 1918. -

I Ntroduction

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-08346-2 - Australia 1944–45: Victory in the Pacific Edited by Peter J . Dean Excerpt More information I NTRODUCTION This book is a sibling of two previous works: Australia 1942: In the Shadow of War and Australia 1943: The Liberation of New Guinea. While following a similar theme and approach, both of the two previous books had a different focus. Australia 1942 was centred on Australia’s first traumatic year of the Pacific War, from the fall of Singapore to the victory in Papua in January 1943. It discussed the battles of 1942 that were fought in the air and sea approaches to the Australian continent and in the islands of the archipelago to Australia’s north. That book not only placed these events in their strategic context but also more broadly addressed the major reforms and issues that occurred in Australian politics, the economy and in the relationship Australia had with Japan in the lead up to the war. It did so in order to provide a broad overview of the changes that Australia underwent as a result of the onset of the Pacific War. Australia 1943 had a somewhat narrower focus. That book focused heavily on Australia’s role in the Southwest Pacific Area (SWPA) during 1943, including its strategic challenges and the broader context of US and Allied strategy. Australia 1943 was much more centred on military opera- tions and strategy. The broader context was provided by an examination of Allied and Japanese strategy in the Pacific as well as the operations undertaken by US forces in the South Pacific Area (SOPAC) and the SWPA. -

IATA Codes for Papua New Guinea

IATA Codes for Papua New Guinea N.B. To check the official, current database of IATA Codes see: http://www.iata.org/publications/Pages/code-search.aspx City State IATA Code Airport Name Web Address Afore AFR Afore Airstrip Agaun AUP Aiambak AIH Aiambak Aiome AIE Aiome Aitape ATP Aitape Aitape TAJ Tadji Aiyura Valley AYU Aiyura Alotau GUR Ama AMF Ama Amanab AMU Amanab Amazon Bay AZB Amboin AMG Amboin Amboin KRJ Karawari Airstrip Ambunti AUJ Ambunti Andekombe ADC Andakombe Angoram AGG Angoram Anguganak AKG Anguganak Annanberg AOB Annanberg April River APR April River Aragip ARP Arawa RAW Arawa City State IATA Code Airport Name Web Address Arona AON Arona Asapa APP Asapa Aseki AEK Aseki Asirim ASZ Asirim Atkamba Mission ABP Atkamba Aua Island AUI Aua Island Aumo AUV Aumo Babase Island MKN Malekolon Baimuru VMU Baindoung BDZ Baindoung Bainyik HYF Hayfields Balimo OPU Bambu BCP Bambu Bamu BMZ Bamu Bapi BPD Bapi Airstrip Bawan BWJ Bawan Bensbach BSP Bensbach Bewani BWP Bewani Bialla, Matalilu, Ewase BAA Bialla Biangabip BPK Biangabip Biaru BRP Biaru Biniguni XBN Biniguni Boang BOV Bodinumu BNM Bodinumu Bomai BMH Bomai Boridi BPB Boridi Bosset BOT Bosset Brahman BRH Brahman 2 City State IATA Code Airport Name Web Address Buin UBI Buin Buka BUA Buki FIN Finschhafen Bulolo BUL Bulolo Bundi BNT Bundi Bunsil BXZ Cape Gloucester CGC Cape Gloucester Cape Orford CPI Cape Rodney CPN Cape Rodney Cape Vogel CVL Castori Islets DOI Doini Chungribu CVB Chungribu Dabo DAO Dabo Dalbertis DLB Dalbertis Daru DAU Daup DAF Daup Debepare DBP Debepare Denglagu Mission -

Table of Contents

Commercial in Confidence Development Proposal Wind Emirau Sustainable economic growth for Papua New Guinea… …with a PNG difference Prepared by Edward Car Wind Australia PO Box 377 Kangaroo Ground Victoria, Australia 3097 Tel: 613 9712 0533 [email protected] www.windaustralia.com July 2004 © Copyright Wind Australia 2003 Commercial in Confidence Wind Emirau Project Table of Contents Executive Summary 3 Background 4 Drivers of change Proposal Overview 8 Objectives 15 Marketing Plan 16 Marketing Objectives 21 Pricing 25 SWOT 30 Implementation Plan 34 Operational Issues 39 Infrastructure Development 44 Benefits 53 Ownership 55 Government Assistance Required 58 Risks 60 Financials 61 Glossary 63 Appendix A Developing Sustainable Commercial Fisheries 64 B Project Location 80 C Fish Aggregating Devices (FAD) 83 D Tuna Exports 1996 – June 2001 84 E Assumptions – Summary 89 F Time to Market Scenario 91 2 Commercial in Confidence Wind Emirau Project Executive Summary An International airport and deep-sea port development on Emirau Island will provide a gateway for Papua New Guinea (PNG) to access international markets and export fresh tuna and seafood and establish the largest fresh tuna market in the world. The airport designed for Boeing 747 and the new Airbus 380 will also provide a staging point for control of the vast PNG Designated Fishing Zone (DFZ). Effectively this increases the level of regulation and compliance on visiting international fishing fleets and provides a way of monitoring their impact. Initially the project focus is on developing commercial artisanal fisheries for St Mathias islanders and marketing high quality hand-fished fresh seafoods under a unique brand that promotes the sustainability of the fisheries, the environment and a values- based society.