Iron Age and Romano-British, by Neil Holbrook

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ms Kate Coggins Sent Via Email To: Request-713266

Chief Executive & Corporate Resources Ms Kate Coggins Date: 8th January 2021 Your Ref: Our Ref: FIDP/015776-20 Sent via email to: Enquiries to: Customer Relations request-713266- Tel: (01454) 868009 [email protected] Email: [email protected] Dear Ms Coggins, RE: FREEDOM OF INFORMATION ACT REQUEST Thank you for your request for information received on 16th December 2020. Further to our acknowledgement of 18th December 2020, I am writing to provide the Council’s response to your enquiry. This is provided at the end of this letter. I trust that your questions have been satisfactorily answered. If you have any questions about this response, then please contact me again via [email protected] or at the address below. If you are not happy with this response you have the right to request an internal review by emailing [email protected]. Please quote the reference number above when contacting the Council again. If you remain dissatisfied with the outcome of the internal review you may apply directly to the Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO). The ICO can be contacted at: The Information Commissioner’s Office, Wycliffe House, Water Lane, Wilmslow, Cheshire, SK9 5AF or via their website at www.ico.org.uk Yours sincerely, Chris Gillett Private Sector Housing Manager cc CECR – Freedom of Information South Gloucestershire Council, Chief Executive & Corporate Resources Department Customer Relations, PO Box 1953, Bristol, BS37 0DB www.southglos.gov.uk FOI request reference: FIDP/015776-20 Request Title: List of Licensed HMOs in Bristol area Date received: 16th December 2020 Service areas: Housing Date responded: 8th January 2021 FOI Request Questions I would be grateful if you would supply a list of addresses for current HMO licensed properties in the Bristol area including the name(s) and correspondence address(es) for the owners. -

Applications and Decisions 5534: Office of the Traffic Commissioner

OFFICE OF THE TRAFFIC COMMISSIONER (WEST OF ENGLAND) APPLICATIONS AND DECISIONS PUBLICATION NUMBER: 5534 PUBLICATION DATE: 22/03/2018 OBJECTION DEADLINE DATE: 12/04/2018 Correspondence should be addressed to: Office of the Traffic Commissioner (West of England) Hillcrest House 386 Harehills Lane Leeds LS9 6NF Telephone: 0300 123 9000 Fax: 0113 248 8521 Website: www.gov.uk/traffic-commissioners The public counter at the above office is open from 9.30am to 4pm Monday to Friday The next edition of Applications and Decisions will be published on: 29/03/2018 Publication Price 60 pence (post free) This publication can be viewed by visiting our website at the above address. It is also available, free of charge, via e-mail. To use this service please send an e-mail with your details to: [email protected] APPLICATIONS AND DECISIONS Important Information All post relating to public inquiries should be sent to: Office of the Traffic Commissioner (West of England) Jubilee House Croydon Street Bristol BS5 0DA The public counter in Bristol is open for the receipt of documents between 9.30am and 4pm Monday to Friday. There is no facility to make payments of any sort at the counter. General Notes Layout and presentation – Entries in each section (other than in section 5) are listed in alphabetical order. Each entry is prefaced by a reference number, which should be quoted in all correspondence or enquiries. Further notes precede each section, where appropriate. Accuracy of publication – Details published of applications reflect information provided by applicants. The Traffic Commissioner cannot be held responsible for applications that contain incorrect information. -

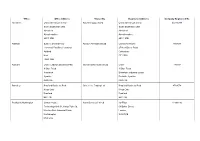

The Driver Hire Network February 2021

Office Office Address Owned By Registered Address Company Registered No Aberdeen Unit 2, Deemouth Centre Ravenscragg Limited Unit 2, Deemouth Centre SC196889 South Esplanade East South Esplanade East Aberdeen Aberdeen Aberdeenshire Aberdeenshire AB11 9PB AB11 9PB Ashford Suite 3, Second Floor Acclaim Recruitment Ltd Camburgh House 4893036 Henwood Pavillion, Henwood 27 New Dover Road Ashford Canterbury Kent CT1 3DN TN24 8DH Ayrshire Unit 3, Ladykirk Business Park Stonefield Recruitment Ltd Unit 3 183397 9 Skye Road 9 Skye Road Prestwick Shawfarm Industrial Estate Ayrshire Pretwick, Ayrshire KA9 2TA KA9 2TA Barnsley Bradford Business Park Driver Hire Trading Ltd Bradford Business Park 4768578 Kings Gate Kings Gate Bradford Bradford BD1 4SJ BD1 4SJ Bedford & Huntingdon Caxton House, Ibara Services Limited 1st Floor, 12306186 Technology Unit 34, Kings Park Rd, 64 Baker Street, Moulton Park Industrial Estate, London, Northampton , W1U 7GB NN3 6LG Belfast Unit 49 Max Recruitment Ltd 137 York Road NI622729 Mallusk Enterprise Park Belfast Newtownabbey Northern Ireland County Antrim BT15 3GZ BT36 4GN Birmingham Central 307 Fox Hollies Road JKL Recruitment Ltd Highfield House Business Centre 9671408 Birmingham Highfield House B27 7PS 1562/1564 Stratford Road Hall Green West Midlands B28 9HA Blackburn 34 Abbey Street DHRB Limited 6 Wicket Grove 6690509 Accrington Clifton Lancashire Swinton BB5 1EB Manchester M27 6ST Bolton Jackson House APDAN Ltd 3 Jackson House 10314758 11 Queen Street 11 Queen Street Leigh Leigh Lancashire Lancashire WN7 4NQ WN7 -

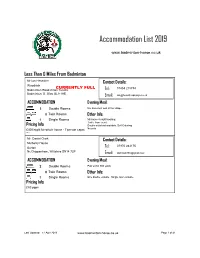

Accommodation List 2019

Accommodation List 2019 www.badminton-horse.co.uk Less Than 0 Miles From Badminton Mr Ian Heseltine Contact Details: Woodside CURRENTLY FULL 01454 218734 Badminton Road Acton Turville Tel: Badminton, S. Glos GL9 1HE Email: [email protected] ACCOMMODATION Evening Meal: 3 Double Rooms No. Excellent pub in the village 0 Twin Rooms Other Info: 1 Single Rooms Minimum 4 night booking. 1 mile from event Pricing Info: Double sofa bed available. Self Catering £400/night for whole house - 7 person capac No pets. ity Mr. Daniel Clark Contact Details: Mulberry House 07970 283175 Burton Tel: Nr.Chippenham, Wiltshire SN14 7LP Email: [email protected] ACCOMMODATION Evening Meal: 2 Double Rooms Pub within 300 yards 0 Twin Rooms Other Info: 1 Single Rooms One double ensuite. Single room ensuite. Pricing Info: £50 pppn Last Updated: 12 April 2019 www.badminton-horse.co.uk Page 1 of 41 Ms. Polly Herbert Contact Details: Dairy Cottage 07770 680094 Crosshands Farm Little Sodbury Tel: , South Glos BS37 6RJ Email: [email protected] ACCOMMODATION Evening Meal: 2 Double Rooms Optional and by arrangement - pubs nearby Twin Rooms Other Info: Single Rooms Currently full from 2nd-4th May. 1 double ensuite £140 pn - 1 room with dbl & 1/2 singles ensuite - £230 pn. Pricing Info: Other contact numbers: 07787557705, 01454 324729. Min stay 3 nights. £120 per night for double room inc. breakfas Plenty of off road parking. Very quiet locaion. t; "200 per night for 4-person room with full o Transportation Available Mrs. Lynn Robertson Contact Details: Ashlea Lakeside Retreat 07870 686306 Mapleridge Lane Horton Tel: Bristol, BS37 6PW Email: [email protected] ACCOMMODATION Evening Meal: 3 Double Rooms 2 Twin Rooms Other Info: 0 Single Rooms 3 x self catering glamping pods -with ensuite shower, underfloor heating etc. -

Accounts of the Constables of Bristol Castle

BRISTOL RECORD SOCIETY'S PUBLICATIONS General Editor: PROFESSOR PATRICK MCGRATH, M.A., Assistant General Editor: MISS ELIZABETH RALPH, M .A., F.S.A. VOL. XXXIV ACCOUNTS OF THE CONSTABLES OF BRISTOL CASTLE IN 1HE THIRTEENTH AND EARLY FOURTEENTH CENTURIES ACCOUNTS OF THE CONSTABLES OF BRISTOL CASTLE IN THE THIR1EENTH AND EARLY FOUR1EENTH CENTURIES EDITED BY MARGARET SHARP Printed for the BRISTOL RECORD SOCIETY 1982 ISSN 0305-8730 © Margaret Sharp Produced for the Society by A1an Sutton Publishing Limited, Gloucester Printed in Great Britain by Redwood Burn Limited Trowbridge CONTENTS Page Abbreviations VI Preface XI Introduction Xlll Pandulf- 1221-24 1 Ralph de Wiliton - 1224-25 5 Burgesses of Bristol - 1224-25 8 Peter de la Mare - 1282-84 10 Peter de la Mare - 1289-91 22 Nicholas Fermbaud - 1294-96 28 Nicholas Fermbaud- 1300-1303 47 Appendix 1 - Lists of Lords of Castle 69 Appendix 2 - Lists of Constables 77 Appendix 3 - Dating 94 Bibliography 97 Index 111 ABBREVIATIONS Abbrev. Plac. Placitorum in domo Capitulari Westmon asteriensi asservatorum abbrevatio ... Ed. W. Dlingworth. Rec. Comm. London, 1811. Ann. Mon. Annales monastici Ed. H.R. Luard. 5v. (R S xxxvi) London, 1864-69. BBC British Borough Charters, 1216-1307. Ed. A. Ballard and J. Tait. 3v. Cambridge 1913-43. BOAS Bristol and Gloucestershire Archaeological Society Transactions (Author's name and the volume number quoted. Full details in bibliography). BIHR Bulletin of the Institute of Historical Research. BM British Museum - Now British Library. Book of Fees Liber Feodorum: the Book of Fees com monly called Testa de Nevill 3v. HMSO 1920-31. Book of Seals Sir Christopher Hatton's Book of Seals Ed. -

GLOUCESTERSHIRE Extracted from the Database of the Milestone Society

Entries in red - require a photograph GLOUCESTERSHIRE Extracted from the database of the Milestone Society National ID Grid Reference Road No. Parish Location Position GL_AVBF05 SP 102 149 UC road (was A40) HAMPNETT West Northleach / Fosse intersection on the verge against wall GL_AVBF08 SP 1457 1409 A40 FARMINGTON New Barn Farm by the road GL_AVBF11 SP 2055 1207 A40 BARRINGTON Barrington turn by the road GL_AVGL01 SP 02971 19802 A436 ANDOVERSFORD E of Andoversford by Whittington turn (assume GL_SWCM07) GL_AVGL02 SP 007 187 A436 DOWDESWELL Kilkenny by the road GL_BAFY07 ST 6731 7100 A4175 OLDLAND West Street, Oldland Common on the verge almost opposite St Annes Drive GL_BAFY07SL ST 6732 7128 A4175 OLDLAND Oldland Common jct High St/West Street on top of wall, left hand side GL_BAFY07SR ST 6733 7127 A4175 OLDLAND Oldland Common jct High St/West Street on top of wall, right hand side GL_BAFY08 ST 6790 7237 A4175 OLDLAND Bath Road, N Common; 50m S Southway Drive on wide verge GL_BAFY09 ST 6815 7384 UC road SISTON Siston Lane, Webbs Heath just South Mangotsfield turn on verge GL_BAFY10 ST 6690 7460 UC road SISTON Carsons Road; 90m N jcn Siston Hill on the verge GL_BAFY11 ST 6643 7593 UC road KINGSWOOD Rodway Hill jct Morley Avenue against wall GL_BAGL15 ST 79334 86674 A46 HAWKESBURY N of A433 jct by the road GL_BAGL18 ST 81277 90989 A46 BOXWELL WITH LEIGHTERTON near Leighterton on grass bank above road GL_BAGL18a ST 80406 89691 A46 DIDMARTON Saddlewood Manor turn by the road GL_BAGL19 ST 823 922 A46 BOXWELL WITH LEIGHTERTON N of Boxwell turn by the road GL_BAGL20 ST 8285 9371 A46 BOXWELL WITH LEIGHTERTON by Lasborough turn on grass verge GL_BAGL23 ST 845 974 A46 HORSLEY Tiltups End by the road GL_BAGL25 ST 8481 9996 A46 NAILSWORTH Whitecroft by former garage (maybe uprooted) GL_BAGL26a SO 848 026 UC road RODBOROUGH Rodborough Manor by the road Registered Charity No 1105688 1 Entries in red - require a photograph GLOUCESTERSHIRE Extracted from the database of the Milestone Society National ID Grid Reference Road No. -

Cheltenham Borough Council and Tewkesbury Borough Council Final Assessment Report November 2016

CHELTENHAM BOROUGH COUNCIL AND TEWKESBURY BOROUGH COUNCIL FINAL ASSESSMENT REPORT NOVEMBER 2016 QUALITY, INTEGRITY, PROFESSIONALISM Knight, Kavanagh & Page Ltd Company No: 9145032 (England) MANAGEMENT CONSULTANTS Registered Office: 1 -2 Frecheville Court, off Knowsley Street, Bury BL9 0UF T: 0161 764 7040 E: [email protected] www.kkp.co.uk CHELTENHAM AND TEWKESBURY COUNCILS BUILT LEISURE AND SPORTS ASSESSMENT REPORT CONTENTS SECTION 1: INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................... 1 SECTION 2: BACKGROUND ........................................................................................... 4 SECTION 3: INDOOR SPORTS FACILITIES ASSESSMENT APPROACH ................... 16 SECTION 4: SPORTS HALLS ........................................................................................ 18 SECTION 5: SWIMMING POOLS ................................................................................... 38 SECTION 6: HEALTH AND FITNESS SUITES ............................................................... 53 SECTION 7: SQUASH COURTS .................................................................................... 62 SECTION 8: INDOOR BOWLS ....................................................................................... 68 SECTION 9: INDOOR TENNIS COURTS ....................................................................... 72 SECTION 10: ATHLETICS ............................................................................................. 75 SECTION 11: COMMUNITY FACILITIES ...................................................................... -

Archdeaconry of Bristol) Which Is Part of the Diocese of Bristol

Bristol Archives Handlist of parish registers, non-conformist registers and bishop’s transcripts Website www.bristolmuseums.org.uk/bristol-archives Online catalogue archives.bristol.gov.uk Email enquiries [email protected] Updated 15 November 2016 1 Parish registers, non-conformist registers and bishop’s transcripts in Bristol Archives This handlist is a guide to the baptism, marriage and burial registers and bishop’s transcripts held at Bristol Archives. Please note that the list does not provide the contents of the records. Also, although it includes covering dates, the registers may not cover every year and there may be gaps in entries. In particular, there are large gaps in many of the bishop’s transcripts. Church of England records Parish registers We hold registers and records of parishes in the City and Deanery of Bristol (later the Archdeaconry of Bristol) which is part of the Diocese of Bristol. These cover: The city of Bristol Some parishes in southern Gloucestershire, north and east of Bristol A few parishes in north Somerset Some registers date from 1538, when parish registers were first introduced. Bishop’s transcripts We hold bishop’s transcripts for the areas listed above, as well as several Wiltshire parishes. We also hold microfiche copies of bishop’s transcripts for a few parishes in the Diocese of Bath and Wells. Bishop’s transcripts are a useful substitute when original registers have not survived. In particular, records of the following churches were destroyed or damaged in the Blitz during the Second World War: St Peter, St Mary le Port, St Paul Bedminster and Temple. -

Gloucestershire Village & Community Agents

Helping older people in Gloucestershire feel more independent, secure, and have a better quality of life May 2014 Gloucestershire Village & Community Agents Managed by GRCC Jointly funded by Gloucestershire Clinical Commissioning Group www.villageagents.org.uk Helping older people in Gloucestershire feel more independent, secure, and have a better quality of life Gloucestershire Village & Community Agents Managed by GRCC Jointly funded by Gloucestershire Clinical Commissioning Group Gloucestershire Village and Key objectives: To give older people easy Community Agents is aimed 3 access to a wide range of primarily at the over 50s but also To help older people in information that will enable them offers assistance to vulnerable 1 Gloucestershire feel more to make informed choices about people in the county. independent, secure, cared for, their present and future needs. and have a better quality of life. The agents provide information To engage older people to To promote local services and support to help people stay 4 enable them to influence and groups, enabling the independent, expand their social 2 future planning and provision. Agent to provide a client with a activities, gain access to a wide community-based solution To provide support to range of services and keep where appropriate. people over the age of 18 involved with their local 5 who are affected by cancer. communities. Partner agencies ² Gloucestershire County Council’s Adult Social Care Helpdesk ² Gloucestershire Clinical Commissioning Group ² Gloucestershire Rural Community -

Full Council Minutes 21St January 2021

WHEATPIECES PARISH COUNCIL FULL COUNCIL MEETING ON THURSDAY 21st JANUARY 2021 AT 7.00PM DUE TO THE CORONAVIRUS PANDEMIC THIS MEETING WAS HELD REMOTELY VIA ZOOM VIDEO CONFERENCING PRESENT: Cllr. Meredith, Cllr. Reid, Cllr. Abel, Cllr. Dempster Cllr. Pullen, Cllr. Shyamapant IN ATTENDANCE: County Cllr. V Smith A Fendt (Community Centre Manager) T Shurmer (Clerk) MINUTES Cllr. Meredith welcomed all to the on-line Wheatpieces Parish Council meeting in these continuing ongoing uncertain times. 963/FC - PUBLIC PARTICIPATION No members of the public were in attendance. 964/FC - APOLOGIES FOR ABSENCE Apologies were received and accepted from Cllr. Mulholland 965/FC - DECLARATIONS OF INTEREST No declarations of interest were made. 966/FC -TO APPROVE THE MINUTES OF THE MEETING HELD ON THURSDAY 1ST OCTOBER 2020 The minutes of the Full Council meeting held on Thursday 1st October 2020 were approved and adopted. Proposed: Cllr. Abel Seconded: Cllr. Dempster Agreed 967/FC – COUNTY COUNCILLOR’S REPORT ➢ County Cllr. Smith had sent various reports from Gloucestershire County Council (GCC) for the meeting, these had been duly circulated to all and were taken as read. ➢ Cllr. Smith enquired if there was an update on the installation of the defibrillator at the Wheatpieces public house. Cllr. Meredith advised that the public house is currently closed due to lockdown and that he will contact the licensees when normality resumes, however, he advised that the defibrillator is for indoor use and could be installed by the maintenance team for the public house. 1 FC Mins – 21/1/2021 (963/FC-977/FC) ➢ Cllr. Smith advised that the M5 jct.9 off road solution is still not finalised and talks are continuing with Highways England for a solution. -

Gosh Locations

GOSH LOCATIONS - MAY POSTAL COUNCIL ALTERNATIVE SECTOR NAME MONTH (DATES) SECTOR BH12 1 Poole Borough Council Poole (Incl Branksome) 29.04.19-02.06.19 BH12 2 Poole Borough Council Albert Road, Poole 29.04.19-02.06.19 BH12 3 Poole Borough Council Poole (Incl Parkstone, Newtown) 29.04.19-02.06.19 BH12 4 Poole Borough Council Rossmore, Alderney, Bournemouth 29.04.19-02.06.19 BH12 5 Poole Borough Council Wallisdown, Talbot Heath, Bournemouth 29.04.19-02.06.19 BH13 6 Poole Borough Council Poole (Incl Branksome Park) 29.04.19-02.06.19 BH13 7 Poole Borough Council Poole (Incl Branksome Park, Canford Cliffs) 29.04.19-02.06.19 BH14 0 Poole Borough Council Poole (Incl Parkstone) 29.04.19-02.06.19 BH14 8 Poole Borough Council Poole (Incl Parkstone, Lilliput) 29.04.19-02.06.19 BH14 9 Poole Borough Council Poole (Incl Parkstone (West)) 29.04.19-02.06.19 BH15 1 Poole Borough Council Lagland Street, Poole 29.04.19-02.06.19 BH15 2 Poole Borough Council Longfleet, Poole 29.04.19-02.06.19 BH15 3 Poole Borough Council Poole (Incl Oakdale) 29.04.19-02.06.19 BH15 4 Poole Borough Council Poole (Incl Hamworthy) 29.04.19-02.06.19 BH17 0 Poole Borough Council Nuffield Ind Est 29.04.19-02.06.19 BH17 7 Poole Borough Council Poole (Incl Waterloo, Upton) 29.04.19-02.06.19 BH17 8 Poole Borough Council Canfold Heath, Poole 29.04.19-02.06.19 BH17 9 Poole Borough Council Canford Heath, Darby's Corner, Poole 29.04.19-02.06.19 BH18 8 Poole Borough Council Hillbourne, Poole 29.04.19-02.06.19 BH18 9 Poole Borough Council Broadstone, Poole 29.04.19-02.06.19 BH16 5 Purbeck -

Rudgeway, Bristol

OFFICE TO LET Rudgeway, Bristol HIGH QUALITY OFFICES WITH ON-SITE CAR PARKING ONLY 3 MILES FROM THE M5/M4 INTERCHANGE Ground Floor Unit 7 Pinkers Court Briarland Office Park Rudgeway Bristol BS35 3QH 1,620 sq ft (150.5 sq m) approx. Unit 7 Pinkers Court, Briarland Office Park, Rudgeway, Bristol, BS35 3QH Location The units on Briarland Office Park all provide high quality Each party is to be responsible for their own legal costs open plan office accommodation within a well managed incurred in the transaction. Briarland Office Park is a successful campus style office and landscaped setting. The specification of this unit development in a rural setting on the main A38 Gloucester includes the following amenities: Business Rates Road approximately 3 miles north of Junction 16 of the M5 providing easy access to the motorway and only 12 miles Interested parties should make their own enquiries to away from Bristol City Centre. Heating and Cooling system South Gloucestershire Council to ascertain the exact LED light fittings rates payable as a change in occupation may trigger an Fitted kitchen adjustment of the ratings assessment. www.voa.gov.uk. Male / Female / Disabled WC facilities 24 hour security We are advised that the Rateable Value for the unit is Onsite gym with shower facilities £18,000 Lease References/Rental Deposits The accommodation is offered by way of a new full Financial and accountancy references may be sought from repairing and insuring lease for a term of years to be any prospective tenant prior to agreement. Prospective agreed. tenants may be required to provide a rental deposit subject to landlords’ discretion.