Fuentes Grecolatinas Y

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Notes Du Mont Royal ←

Notes du mont Royal www.notesdumontroyal.com 쐰 Cette œuvre est hébergée sur « No- tes du mont Royal » dans le cadre d’un exposé gratuit sur la littérature. SOURCE DES IMAGES Google Livres ÏHISTORIÆ» ’*POETICÆ,H ’SCRIPTORES ANTIQJLW ’APOLLODORUS Atbmimfis. PTOLEMÆUS mm. 1v. 1c o N o N Grammaticm. PARTHMEN IUs mima; ANTON INUS immuns. Græcè 8c Latine. Jccgfi’è’re hem: Nm é Milice: mafia; la PARISIIIS. Typis F. u c u E T. Profiant apud R. S c o T "r, ü Bibliopolam Londinenfem. v MDCLxxm I - fluerez I L L u s (R0TIR 1’ D.JOSEPHO WILLIAMSON; 22141111 Lamina, SERENISSIMOMCAROLOIL - MAG. 31m: .FRANC. ET Hua. REGI - ’ A CONSILus InNTERIORIBuS, ETA SECRETIS STATus. , Xfiant’ in me , ".V I R "7CLARIS promerità 1m SIME) , magna diuturna. ,Sponte tuâ; nullo meo merito, defcendifli etiam- ad maclé benewolentiâ, qué Genti: a bnju: Epifiola Dcdicatoria: ’ buju: (9* (thorium ,literato: homi- ne: compleâîerù. Necfpem, nec cogitotionem guidon: foui, dignum aliquz’d tonifiât benefic’iis, unqmm reponencli ; aequo ’èm’mpotiebatur id ont fortune TUÆ magnitudo, ont ’mèæ agami; Non Âceflb interim juflâ debitâq; prodicatione ubiq; t’efl’ari toutim: Tibi dobere me, quantum firme? homo bomini poteflfiugi hâcÇnullâ’aliânzle wifi) gratit’udifii: mm fighificonclæ’curâ adduôîm,Nomini T110 ho: li- bella: infrrz’pfi. Molui Forum mo- j dellw boom, quÆm-mz’nù: group. Quanquam ’confllz’o huic meolz’lluçl jetiompotracinaritpoflîtguàd non in: l’pridem (quetzal al? lau’mqriz’tizofiu- diorum meOrüm’rationemTc ex- ,peétare * ’ Epiflola. Dedicatoria.’ wpeâare dicerer. Obtempero mi: 5 etiam ad exiflimotionù mon: periculnm. Ha: tomèn qua- liocnnque flint, non profil: , mi fiera, npnd TE wilefcent. -

Clas109.04 Rebirth Demeter & Hades

CLAS109.04 REBIRTH M Maurizio ch.4.1 HISTORY—Homeric Hymn to Demeter before class: skim HISTORY context; refer to leading questions; focus on ancient texts Active Reading FOCUS • H.Hom.2 & Plut.Mor. cf. CR04 H.Hom.Cer. G. Nagy trans. (Maurizio p.163‐174 is fine) use CR04 Plutarch Moralia: Isis & Osiris 15‐16 (Plut.Mor.357A‐D) NB read for one hour, taking notes (fill in worksheets) RAW notes & post discussion question @11h00 W Maurizio ch.4.3 COMPARE—In the Desert by the Early Grass before class: skim COMPARE context; refer to leading questions; focus on ancient text Active Reading FOCUS • Early Grass (edin‐na u2 saĝ‐ĝa2‐ke4) use CR04 Jacobsen 1987 translation (Maurizio p.188‐194 is NOT fine) NB read for one hour, taking notes; finish previous as necessary RAW notes & post discussion question @12h00 F Maurizio ch.4.2 THEORY—Foley 1994 before class: skim also modern 4.4 RECEPTION paragraph synopsis of Foley, H. 1994. “Question of Origins.” Womens Studies 23.3:193‐215 NB read for one hour, practice summarizing; finish previous as necessary tl; dr & post discussion responses @11h00 Q04 • QUOTE QUIZ Gen.6‐11, Aesch.Prom., H.Hom.Cer., Plut.Mor.357A‐D; Early Grass FINAL notes @23h59 DRAFT 01 @23h59 • following guidelines DEMETER & HADES How does myth represent the natural world (e.g. pre‐scientific explanation)? How does myth represent religious ritual? How does myth represent social order? Homeric Hymn to Demeter1 G. Nagy 1 I begin to sing of Demeter, the holy goddess with the beautiful hair. -

Read Book Greek Mythology Kindle

GREEK MYTHOLOGY PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Ken Jennings,Mike Lowery | 160 pages | 01 Mar 2014 | SIMON & SCHUSTER | 9781442473300 | English | New York, United States Greek Mythology: Gods, Characters & Stories - HISTORY Hades knew that if someone ate food in the Underworld, they could never really escape the world of the dead. Persephone was shortly after reunited with her mother. However, Demeter was furious when she heard about the pomegranate seeds. Zeus then proposed a compromise: for every seed Persephone had eaten, she would spend a month with Hades. Thus, Persephone would travel to the Underworld every six months during which time Demeter would mourn and the earth with her. But after six months, Persephone would return to her and Demeter would be happy again and the earth would blossom once again! Cecrops, the first king of Attica, had named his city after him, Cecropia. However, the gods of Olympus saw this lovely piece of land and wanted to name it after them and become its patron. The most persistent rivals were Poseidon, the god of the sea, and Athena, the goddess of wisdom. To solve their dispute, Zeus decided that each of them would present a gift to the city and the people of Cecropia would decide which gift was the best, and therefore which god would be the patron of the city. One sunny day, Cecrops and the residents of the city went up to a high hill to watch the gods presenting their gifts. Poseidon was the first to present his gift. He struck a rock with his trident and caused a spring of water to gush forth from the ground. -

2019 Stanford CERTAMEN ADVANCED LEVEL ROUND 1 TU

2019 Stanford CERTAMEN ADVANCED LEVEL ROUND 1 TU 1. Translate this sentence into English: Servābuntne nōs Rōmānī, sī Persae īrātī vēnerint? WILL THE ROMANS SAVE US IF THE ANGRY PERSIANS COME? B1: What kind of conditional is illustrated in that sentence? FUTURE MORE VIVID B2: Now translate this sentence into English: Haec nōn loquerēris nisi tam stultus essēs. YOU WOULD NOT SAY THESE THINGS IF YOU WERE NOT SO STUPID TU 2. What versatile author may be the originator of satire, but is more famous for writing fabulae praetextae, fabulae palliatae, and the Annales? (QUINTUS) ENNIUS B1: What silver age author remarked that Ennius had three hearts on account of his trilingualism? AULUS GELLIUS B2: Give one example either a fabula praetexta or a fabula palliata of Ennius. AMBRACIA, CAUPUNCULA, PANCRATIASTES TU 3. What modern slang word, deriving from the Latin word for “four,” is defined by the Urban Dictionary as “crew, posse, gang; an informal group of individuals with a common identity and a sense of solidarity”? SQUAD B1: What modern slang word, deriving from a Latin word meaning “bend”, means “subtly or not-so-subtly showing off your accomplishments or possessions”? FLEX B2: What modern slang word, deriving from a Latin word meaning “end” and defined by the Urban Dictionary as “a word that modern teens and preteens say even though they have absolutely no idea what it really means,” roughly means “getting around issues or problems in a slick or easy way”? FINESSE TU 4. Who elevated his son Diadumenianus to the rank of Caesar when he became emperor in 217 A.D.? MACRINUS B1: Where did Macrinus arrange for the assisination of Caracalla? CARRHAE/EDESSA B2: What was the name of the person who actually did the stabbing of Caracalla? JULIUS MARTIALIS TU 5. -

Quaestiones De Homerico Hymno in Cererem

Pfl 4167 .G8 Copy 1 QUAESTIONES DE HOMERICO HYMNO IN CEREREM DISSERTATIO INAUGURALIS PHILOLOGIICA QUAM CONCESSU ET AUCTOEITATE AMPLISSIMI PHILOSOPHOEUM ORDmiS m ACADEMIA FRIDERICIANA HALENSI CUM VITEBERaENSI CONSOCIATA AD SUMMOS IN PHILOSOPHIA HONORES RITE CAPESSENDOS DIE XYII MENSIS MAII A. MDOCCLXXII HORA XI IN AUDITORIO MAXIMO UNA CUM THESIBUS PUBLICE DEFENDET AUCTOE OTILELML8 OSCAll OUTSCHE SAXO -BORUSSr.- /^^ /,:> ADVERSARIORUM PARTES SUSCIPIENT M. Kleemnan, dr. ph. G. VlELUF, CAND. PH. HALIS SAXONUM FoRMis Hendelxis. ^ N^^» ^'^l'^ ^6-d43394 Homeri maiores qui vocantiir hymni iit eiusdem paene generis omnes (praeter h. VIII) sunt et ad Homeri exemplar conformati quadam propinquitate iunguntur, ita multum ab Orphicis hymnis absunt et a secretis iJlorum rationibus vehe- menter recedunt. Eorundem tamen tanta est diversitas, ut omnes docti viri consentiant, singulos hymnos sui quasi iuris esse neque eidem haec carmina poetae aut aetati posse adscribi. lam sermonis et verborum usus quantae sint differentiae do- ctis quaestionibus nuper Fietkavius, Windischius, Koehnius, alii explicare coeperunt, eorumque disputationibus effectum est, ut hymnorum inter se et ab Homeri carminibus discrepantem artem grammaticam, metricam, proprietatem dicendi melius perspiciamus. Illorum ad commentationes reiicimus, si qui singulas differentias cognoscere velint, generales autem, quae intercedunt, paucis exponere iuvat. Bina carmina (si hymnos in Apollinem unum ducimus) tam artem quam consilium diver- sum sequuntur. Mercurii prope abest a Veneris carmine pariter atque Apollinis a Cereris laudibus; ilii sunt lepidi, festivi, hi- lares et ad delicias describendas propensi, hi severe celebrant deum non sine tacita verecundia locosque priscis caerimoniis sacros, fata narrant, collata praesertim in proavos beneficia laudant. Hymnus autem in Cererem eo etiam ab Apollinis differt carmine, quod magis exornatus rebus salutariter inven- tis civitatem Eleusinis praedicat et aperte sacerdotum auctori- tate compositus Atticam originem certis indiciis prodit. -

The Eleusinian Mysteries & Rites

THE ELEUSINIAN MYSTERIES & RITES DUDLEY WRIGHT THE ELEUSINIAN MYSTERIES AND RITES THE ELEUSINIAN MYSTERIES ^ RITES BY DUDLEY WRIGHT INTRODUCTION BY THE REV. J. FORT NEWTON, D.Litt., D.D. Past Grand Chaplain of the Grand Lodge of lowa^ U.S.tA. THE THEOSOPHICAL PUBLISHING HOUSE I UPPER WOBURN PLACE LONDON, W.C.I "THE SQUARE & COMPASS," 4, 412, Beach Court, Denver, Colo. U.S.A. n CO 5 U ^ PREFACE AT one time the Mysteries of the various nations were the only vehicle of religion throughout the world, and it is not impossible that the very name of religion might have become obsolete but for the support of the periodical celebrations which preserved all the forms and ceremonials, rites and practices of sacred worship. With regard to the connection, supposed or real, between Freemasonry and the Mysteries, it is a remarkable coincidence that there is scarcely a single ceremony in the former that has not its corresponding rite in one or other of the Ancient Mysteries. The question as to which is the original is an important one to the student. The Masonic antiquarian maintains that Freemasonry is not a scion snatched with a violent hand from the Mysteries—whether Pythagorean, Hermetic, Samothracian, Eleusinian, Drusian, Druidical, or the Uke—but is the original institution, from which all the Mysteries were derived. 8 ELEUSINIAN MYSTERIES AND RITES In the opinion of the renowned Dr. George Ohver : *' There is ample testimony to estabhsh the fact that the Mysteries of all nations were originally the same, and diversified only by the accidental circumstances of local situation and pohtical economy." The original foundation of the Mysteries has, however, never been established. -

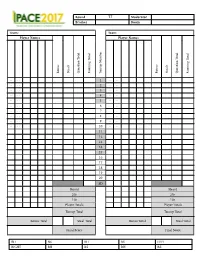

Round Moderator Bracket Room Team

Round 17 Moderator Bracket Room Team: Team: Player Names Player Names Steals Bonus Steals Question Total Running Total Bonus Running Total Tossup Number Question Total .. .. 1 .. .. .. .. 2 .. .. .. .. 3 .. .. .. .. 4 .. .. .. .. 5 .. .. .. .. 6 .. .. .. .. 7 .. .. .. .. 8 .. .. .. .. 9 .. .. .. .. 10 .. .. 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 SD Heard Heard 20s 20s 10s 10s Player Totals Player Totals Tossup Total Tossup Total Bonus Total Steal Total Bonus Total Steal Total Final Score Final Score RH RS BH BS LEFT RIGHT BH BS RH RS PACE NSC 2017 - Round 17 - Tossups 1. The HIV Rev response element forms a complex with the Crm1 protein that localizes to this structure. A group of proteins that form the Y-complex on this structure have consecutive repeats of phenylalanine-glycine. The Ran GTPase shuttles molecules with an NES through this structure with the help of exportin and importin. A common progeria is caused by a defect in the class V intermediate filaments on the interior of this structure, which are called (*) lamins. This structure has small holes called porins and completely dissolves during prometaphase so that the chromosomes can bind to spindle fibers. This double membrane is continuous with the endoplasmic reticulum. For 10 points, name this envelope that surrounds the cell's genetic material. ANSWER: nuclear membrane [or nuclear envelope; or nuclear lamina; or NE; prompt on nucleus or word forms] <Silverman> 2. This man's work was corrected by Erasmus Reinhold, the first person to make tables based on his theories. Some of his ideas were first communicated in the Narratio Prima by his student, Georges Joachim Rheticus. -

Greek Mythology

Greek mythology focus on the Trojan War and its aftermath. Two poems by Homer's near contemporary Hesiod, the Theogony and the Works and Days, contain accounts of the genesis of the world, the succession of divine rulers, the succession of human ages, the origin of human woes, and the ori- gin of sacrificial practices. Myths are also preserved in the Homeric Hymns, in fragments of epic poems of the Epic Cycle, in lyric poems, in the works of the tragedians of the fifth century BC, in writings of scholars and poets of the Hellenistic Age, and in texts from the time of the Roman Empire by writers such as Plutarch and Pausanias. Archaeological findings provide a principal source of detail about Greek mythology, with gods and heroes featured prominently in the decoration of many arti- facts. Geometric designs on pottery of the eighth cen- tury BC depict scenes from the Trojan cycle as well as the adventures of Heracles. In the succeeding Archaic, Classical, and Hellenistic periods, Homeric and various other mythological scenes appear, supplementing the ex- isting literary evidence.[2] Greek mythology has had an extensive influence on the culture, arts, and literature of Western civilization and remains part of Western heritage and language. Poets and artists from ancient times to the present have derived inspiration from Greek mythology and have discovered contemporary significance and rele- vance in the themes.[3] Bust of Zeus, Otricoli (Sala Rotonda, Museo Pio-Clementino, Vatican). 1 Sources Greek mythology is the body of myths and teachings that Greek mythology is known today primarily from Greek belong to the ancient Greeks, concerning their gods and literature and representations on visual media dating from heroes, the nature of the world, and the origins and signif- the Geometric period from c. -

Homeric Inn to Demeter” Modernity: Motherhood Constellation and Adolescent Separation-Individuation1 by Pasquale Scarnera*

Symmetric Logic and “Homeric inn to Demeter” modernity: motherhood constellation and adolescent separation-individuation1 by Pasquale Scarnera* Introduction The ancient religiosity was codified by myths. E. Vandiver (2000) has combined the theoretical approaches of the field to an operative definition of the myth: … traditional stories a society tells itself that encode or represent the world-view, beliefs, principles, and often fears of that society. As such, myths offer insight into what a specific culture thinks about the nature of the world in general and about key questions, such as: the nature and function of the gods; humans’ relationships to the gods; what it mean to be human; the two sexes’ relationship to one another (p. 15). Myths, being cultural productions representing a model of the society and for the society as well, were expressly modified by poets, philosophers (Radcliffe, 2004) or itinerant priests (Torjussen, 2008). The constancy and adjustment in time and space were typical of the Greek religiosity and were partially induced by the lack of central organizations, sacred texts or doctrines to regulate religious affairs, thus, unlike Christianity it included the act of choosing in the religious field (Larson, 2007). Furthermore, the Greek polytheist paradigm was enclosing, namely welcoming and tolerating various divinities; on the contrary, the monotheist paradigm, which is excluding, cannot welcome divinities different from the worshipped one. Thus, the knowledge of the creation and transmission of cultural production can help us better understand the resilience of ancient religiosity. Ontology of knowledge and religious mental representations The contemporary scientific knowledge is based on the distinction between the knowing subject and the known object. -

Who's Who in Classical Mythology

Who’s Who in Classical Mythology The Routledge Who’s Who series Accessible, authoritative and enlightening, these are the definitive biographical guides to a diverse range of subjects drawn from literature and the arts, history and politics, religion and mythology. Who’s Who in Ancient Egypt Michael Rice Who’s Who in the Ancient Near East Gwendolyn Leick Who’s Who in Christianity Lavinia Cohn-Sherbok Who’s Who in Classical Mythology Michael Grant and John Hazel Who’s Who in Contemporary Gay and Lesbian History Edited by Robert Aldrich and Garry Wotherspoon Who’s Who in Contemporary Women’s Writing Edited by Jane Eldridge Miller Who’s Who in Contemporary World Theatre Edited by Daniel Meyer-Dinkegräfe Who’s Who in Dickens Donald Hawes Who’s Who in Europe 1450–1750 Henry Kamen Who’s Who in Gay and Lesbian History Edited by Robert Aldrich and Garry Wotherspoon Who’s Who in the Greek World John Hazel Who’s Who in Jewish History Joan Comay, revised by Lavinia Cohn-Sherbok Who’s Who in Military History John Keegan and Andrew Wheatcroft Who’s Who in Modern History Alan Palmer Who’s Who in Nazi Germany Robert S.Wistrich Who’s Who in the New Testament Ronald Brownrigg Who’s Who in Non-Classical Mythology Egerton Sykes, revised by Alan Kendall Who’s Who in the Old Testament Joan Comay Who’s Who in the Roman World John Hazel Who’s Who in Russia since 1900 Martin McCauley Who’s Who in Shakespeare Peter Quennell and Hamish Johnson Who’s Who of Twentieth-Century Novelists Tim Woods Who’s Who in Twentieth-Century World Poetry Edited by Mark Willhardt -

The Homeric Hymns 64 Irene De Jong

Characterization in Ancient Greek Literature Studies in Ancient Greek Narrative, Volume 4 Edited by Koen De Temmerman Evert van Emde Boas leiden | boston For use by the Author only | © 2018 Koninklijke Brill NV Contents Preface ix Note on Citation and Abbreviations xi Glossary xii Character and Characterization in Ancient Greek Literature: An Introduction 1 Koen De Temmerman and Evert van Emde Boas part 1 Epic and Elegiac Poetry 1 Homer 27 Irene de Jong 2 Hesiod 46 Hugo Koning 3 The Homeric Hymns 64 Irene de Jong 4 Apollonius of Rhodes 80 Jacqueline Klooster 5 Callimachus 100 Annette Harder 6 Theocritus 116 Jacqueline Klooster part 2 Historiography 7 Herodotus 135 Mathieu de Bakker For use by the Author only | © 2018 Koninklijke Brill NV vi contents 8 Thucydides 153 Tim Rood 9 Xenophon 172 Tim Rood 10 Polybius 191 Luke Pitcher 11 Appian 207 Luke Pitcher 12 Cassius Dio 221 Luke Pitcher 13 Herodian 236 Luke Pitcher 14 Josephus 251 Jan Willem van Henten and Luuk Huitink 15 Pausanias 271 Maria Pretzler part 3 Choral Lyric 16 Pindar and Bacchylides 293 Bruno Currie part 4 Drama 17 Aeschylus 317 Evert van Emde Boas 18 Sophocles 337 Michael Lloyd For use by the Author only | © 2018 Koninklijke Brill NV contents vii 19 Euripides 355 Evert van Emde Boas 20 Aristophanes 375 Angus Bowie 21 Menander 391 Peter Brown part 5 Oratory 22 Lysias 409 Mathieu de Bakker 23 Aeschines and Demosthenes 428 Nancy Worman part 6 Philosophy 24 Plato 445 Kathryn Morgan part 7 Biography 25 Xenophon 467 Luuk Huitink 26 Plutarch 486 Judith Mossman 27 Philostratus 503 Kristoffel Demoen For use by the Author only | © 2018 Koninklijke Brill NV viii contents part 8 Between Philosophy and Rhetoric 28 Dio Chrysostom 523 Dimitri Kasprzyk 29 Lucian 542 Owen Hodkinson part 9 The Novel 30 Chariton 561 Koen De Temmerman 31 Xenophon of Ephesus 578 Koen De Temmerman 32 Achilles Tatius 591 Koen De Temmerman 33 Longus 608 J.R. -

As Hollis Attica in Hellenistic Poetry

A. S. HOLLIS ATTICA IN HELLENISTIC POETRY aus: Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik 93 (1992) 1–15 © Dr. Rudolf Habelt GmbH, Bonn 1 ATTICA IN HELLENISTIC POETRY Perhaps the main reason for the continuing vitality and attraction of studies in the affairs of Attica, whether they centre on local history, topography, cult and myth, social and political organization or everyday life, is the discovery of inscriptions which gradually increase our knowledge, however problematic their interpretation may be. Turning to the literary sources, in the valuable book by David Whitehead, The Demes of Attica 508/7 - ca. 250 B.C.,1 we find them classified under five headings: Comedy, Tragedy, History, Oratory and Political Thought.2 Of these, Oratory is described as 'indisputably the richest of the genres' in both quantity and quality, though Whitehead devotes most space (a whole chapter) to 'The Deme in Comedy'. Since he even pays some attention to lexicographers such as Harpocration, Hesychius and Stephanus of Byzantium, the total absence of Hellenistic poets (apart from Comedians) is surprising: Callimachus does not figure even in the account of the cult of Hecale in her own deme (pp. 210-211), although Callimachus' famous epyllion is our only witness for the annual banquet with which Hecale was honoured.3 Other scholars likewise fail to quote Hellenistic poets when their evidence could be useful. Why this neglect? Of course the style of the learned poets tends to be difficult and obscure; most of their poems are preserved only in tantalizing fragments, of which the text and context can be upset by new papyrus discoveries.