Narratives and Places of Cultural Opposition in the Visual Arts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bauhaus Networking Ideas and Practice NETWORKING IDEAS and PRACTICE Impressum

Museum of Contemporary Art Zagreb Zagreb, 2015 Bauhaus networking ideas and practice NETWORKING IDEAS AND PRACTICE Impressum Proofreading Vesna Meštrić Jadranka Vinterhalter Catalogue Bauhaus – Photographs Ј Archives of Yugoslavia, Belgrade networking Ј Bauhaus-Archiv Berlin Ј Bauhaus-Universitat Weimar, Archiv der Moderne ideas Ј Croatian Architects Association Archive, Graphic design Zagreb Aleksandra Mudrovčić and practice Ј Croatian Museum of Architecture of the Croatian Academy of Sciences and Arts, Zagreb Ј Dragan Živadinov’s personal archive, Ljubljana Printing Ј Graz University of Technology Archives Print Grupa, Zagreb Ј Gustav Bohutinsky’s personal archive, Faculty of Architecture, Zagreb Ј Ivan Picelj’s Archives and Library, Contributors Museum of Contemporary Art, Zagreb Aida Abadžić Hodžić, Éva Bajkay, Ј Jernej Kraigher’s personal archive, Print run Dubravko Bačić, Ruth Betlheim, Ljubljana 300 Regina Bittner, Iva Ceraj, Ј Katarina Bebler’s personal archive, Publisher Zrinka Ivković,Tvrtko Jakovina, Ljubljana Muzej suvremene umjetnosti Zagreb Jasna Jakšić, Nataša Jakšić, Ј Klassik Stiftung Weimar © 2015 Muzej suvremene umjetnosti / Avenija Dubrovnik 17, Andrea Klobučar, Peter Krečič, Ј Marie-Luise Betlheim Collection, Zagreb Museum of Contemporary Art, Zagreb 10010 Zagreb, Hrvatska Lovorka Magaš Bilandžić, Vesna Ј Marija Vovk’s personal archive, Ljubljana ISBN: 978-953-7615-84-0 tel. +385 1 60 52 700 Meštrić, Antonija Mlikota, Maroje Ј Modern Gallery Ljubljanja fax. +385 1 60 52 798 Mrduljaš, Ana Ofak, Peter Peer, Ј Monica Stadler’s personal archive A CIP catalogue record for this book e-mail: [email protected] Bojana Pejić, Michael Siebenbrodt, Ј Museum of Architecture and Design, is available from the National and www.msu.hr Barbara Sterle Vurnik, Karin Šerman, Ljubljana University Library in Zagreb under no. -

Non-Aligned Modernity / Modernità Non Allineata

Milan, 16 September 2016 , FM Centro per l'Arte Contemporanea, the new center for contemporary art and collecting inaugurated last April at the Frigoriferi Milanesi, reopens its exhibition season on 26 October with three new exhibitions and a cycle of meetings aimed at art collectors. NON-ALIGNED MODERNITY / MODERNITÀ NON ALLINEATA Eastern-European Art and Archives from the Marinko Sudac Collection / Arte e Archivi dell’Est Europa dalla Collezione Marinko Sudac 27 October – 23 December 2016 Curated by Marco Scotini, in collaboration with Andris Brinkmanis and Lorenzo Paini 25 October 2016, 11 am - press preview 26 October 2016, 6 pm - opening event 27 October 2016, 7 pm - exhibition talk Under the patronage of: Republic of Croatia, Ministry of Foreign and European Affairs Consolato Generale della Repubblica di Croazia, Milano Ente Nazionale Croato per il Turismo, Milano After L’Inarchiviabile/The Unarchivable , an extensive review of the Italian art in the 1970s, FM Centro per l’Arte Contemporanea’s exhibition program continues with a second event, once again concerning an artistic scene that is less known and yet to be discovered. Despite the international prestige of some of its representatives, this is an almost submerged reality but one that represents an exceptional contribution to the history of art in the second half of the twentieth century. Non-Aligned Modernity not only tackles art in the nations of Eastern Europe but attempts to investigate an anomalous and anything but marginal chapter in their history, which cannot be framed within the ideology of the Soviet Bloc nor within the liberalistic model of Western democracies. -

Zivot Umjetnosti, 7-8, 1968, Izdavac

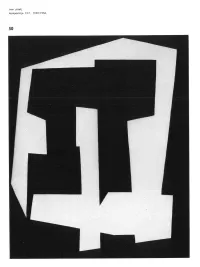

ivan picelj kompozicija 15/1, 1952./1956. 50 vlado kristl varijanta, 1958./1962. 51 igor zidić apstrahiranje predmetnosti i oblici apstrakcije u hrvatskom slikarstvu 1951/1968. bilješke aleksandar srnec kompozicija, 1956. 52 Opće je mjesto kritičke svijesti da pojam apstraktne umjetnosti ne znači više ono što je značio prije pola stoljeća, pa ni ono što je značio još prije dvadeset godina. Da je razvoj ove umjetnosti tada prestao, da se ona uslijed iscrpljenja urušila u se svejedno bi smo bili u prilici da zapazimo oscilacije značenja pojma. Domašaj svijesti u naporu da razumije i od redi pojavu ne može izbjeći ograničenjima same svi jesti. Zato se pred različitim očima svaka pojava raspada u toliko različitih pojavnosti koliko je razli čitih promatrača; ni jedan vid ne govori o gleda nome toliko koliko o viđenome — što će reći, da se, u svemu što gleda, oko i samo ogleda: vid je, tako đer, dio viđenoga. Ne treba, stoga, pomišljati da je 1918. ili 1948. po stojala apsolutna suglasnost o značenju pojma ap straktne umjetnosti ili pak, da će ikad i postojati. Ali činjenica da apstraktna umjetnost nije do sada »potrošila« oblike svog postojanja kaže nam da se pojam o njoj mora izmijeniti već i zbog toga što se ona mijenjala. Slikovito će nam otvoriti put razumijevanju naravi njezina početka jedan nedovoljno iskorišten aspekt predobro poznate priče o izvrnutoj slici u ateljeu Kandinskoga. Zatomimo li znatiželju povjesnika, koji u datumu događaja (1908.) vidi razlog pričanja, obratit ćemo pozornost okolnostima u kojima je vi đena pseudoprva pseudoapstraktna slika, u kojima je ta i takva slika — ni prva među apstraktnim, ni apstraktna među figurativnim — bila, dakle, pse- udoviđena. -

GORGONA 1959 – 1968 Independent Artistic Practices in Zagreb Retrospective Exhibition from the Marinko Sudac Collection

GORGONA 1959 – 1968 Independent Artistic Practices in Zagreb Retrospective Exhibition from the Marinko Sudac Collection 14 September 2019 – 5 January 2020 During the period of socialism, art in Yugoslavia followed a different path from that in Hungary. Furthermore, its issues, reference points and axes were very different from the trends present in other Eastern Bloc countries. Looking at the situation using traditional concepts and discourse of art in Hungary, one can see the difference in the artistic life and cultural politics of those decades in Yugoslavia, which was between East and West at that time. The Gorgona group was founded according to the idea of Josip Vaništa and was active as an informal group of painters, sculptors and art critics in Zagreb since 1959. The members were Dimitrije Bašičević-Mangelos, Miljenko Horvat, Marijan Jevšovar, Julije Knifer, Ivan Kožarić, Matko Meštrović, RadoslavPutar, Đuro Seder, and Josip Vaništa. The activities of the group consisted of meetings at the Faculty of Architecture, in their flats or ateliers, in collective works (questionnaires, walks in nature, answering questions or tasks assigned to them or collective actions). In the rented space of a picture-framing workshop in Zagreb, which they called Studio G and independently ran, from 1961 to 1963 they organized 14 exhibitions of various topics - from solo and collective exhibitions by group's members and foreign exhibitors to topical exhibitions. The group published its anti-magazine Gorgona, one of the first samizdats post WWII. Eleven issues came out from 1961 to 1966, representing what would only later be called a book as artwork. The authors were Gorgona members or guests (such as Victor Vasarely or Dieter Roth), and several unpublished drafts were made, including three by Pierre Manzoni. -

DESIGN and INDUSTRY: the Role and Impact of Industrial Design in Post-War Yugoslavia

Special Call “Design Policies: Between Dictatorship and Resistance” | December 2015 Editorial DESIGN AND INDUSTRY: The Role and Impact of Industrial Design in Post-War Yugoslavia Dora Vanette, Parsons The New School for Design, New York Key Words Yugoslavia, midcentury, industrial design, media ABSTRACT This study offers an overview of the design developments in the period following the Second World War in Yugoslavia and indicate the points of contact and departure between an emerging generation of architects and designers and state sanctioned design. The goal of this paper is to trace the development of the discipline of industrial design in this context, and argue for its revolutionary position in the development of a modern Yugoslavia. INTRODUCTION Following the end of World War II a new generation of architects and designers emerged in Yugoslavia, seeking to mediate socialist ideology with modernist forms. The group, mostly gathered around the progressive environment of the newly established Academy of Applied Art (1949-1955), attempted to promote art and design that was highly functional and aesthetically pleasing, and most importantly, available to all. What began as a probing of design terminology became a wide-reaching attempt to 1/15 www.iade.pt/unidcom/radicaldesignist | ISSN 1646-5288 promote modernist design as the appropriate expression of contemporary life. Through forming design organizations and developing relationships with manufacturers, the designers strove to bring their products to the market, at the same time utilizing various design publications in an attempt to educate the public on what was believed to be proper design. Finally, these ideas were disseminated to an international public through participation and organization of design fairs. -

Conflicting Visions of Modernity and the Post-War Modern

Socialism and Modernity Ljiljana Kolešnik 107 • • LjiLjana KoLešniK Conflicting Visions of Modernity and the Post-war Modern art Socialism and Modernity Ljiljana Kolešnik Conflicting Visions of Modernity and the Post-war Modern art 109 In the political and cultural sense, the period between the end of World War II and the early of the post-war Yugoslav society. In the mid-fifties this heroic role of the collective - seventies was undoubtedly one of the most dynamic and complex episodes in the recent as it was defined in the early post- war period - started to change and at the end of world history. Thanks to the general enthusiasm of the post-war modernisation and the decade it was openly challenged by re-evaluated notion of (creative) individuality. endless faith in science and technology, it generated the modern urban (post)industrial Heroism was now bestowed on the individual artistic gesture and a there emerged a society of the second half of the 20th century. Given the degree and scope of wartime completely different type of abstract art that which proved to be much closer to the destruction, positive impacts of the modernisation process, which truly began only after system of values of the consumer society. Almost mythical projection of individualism as Marshall’s plan was adopted in 1947, were most evident on the European continent. its mainstay and gestural abstraction offered the concept of art as an autonomous field of Due to hard work, creativity and readiness of all classes to contribute to building of reality framing the artist’s everyday 'struggle' to finding means of expression and design a new society in the early post-war period, the strenuous phase of reconstruction in methods that give the possibility of releasing profoundly unconscious, archetypal layers most European countries was over in the mid-fifties. -

Ovdje Riječ, Ipak Je to Po Svoj Prilici Bio Hrvač, Što Bi Se Moglo Zaključiti Na Temelju Snažnih Ramenih I Leđnih Mišića

HRVATSKA UMJETNOST Povijest i spomenici Izdavač Institut za povijest umjetnosti, Zagreb Za izdavača Milan Pelc Recenzenti Sanja Cvetnić Marina Vicelja Glavni urednik Milan Pelc Uredništvo Vladimir P. Goss Tonko Maroević Milan Pelc Petar Prelog Lektura Mirko Peti Likovno i grafičko oblikovanje Franjo Kiš, ArTresor naklada, Zagreb Tisak ISBN: 978-953-6106-79-0 CIP HRVATSKA UMJETNOST Povijest i spomenici Zagreb 2010. Predgovor va je knjiga nastala iz želje i potrebe da se na obuhvatan, pregledan i koliko je moguće iscrpan način prikaže bogatstvo i raznolikost hrvatske umjetničke baštine u prošlosti i suvremenosti. Zamišljena je Okao vodič kroz povijest hrvatske likovne umjetnosti, arhitekture, gradogradnje, vizualne kulture i di- zajna od antičkih vremena do suvremenoga doba s osvrtom na glavne odrednice umjetničkog stvaralaštva te na istaknute autore i spomenike koji su nastajali tijekom razdoblja od dva i pol tisućljeća u zemlji čiji se politički krajobraz tijekom povijesnih razdoblja znatno mijenjao. Premda su u tako zamišljenom povijesnom ciceroneu svoje mjesto našli i najvažniji umjetnici koji su djelovali izvan domovine, žarište je ovog pregleda na umjetničkoj baštini Hrvatske u njezinim suvremenim granicama. Katkad se pokazalo nužnim da se te granice preskoče, odnosno da se u pregled – uvažavajući zadanosti povijesnih određenja – uključe i neki spomenici koji su danas u susjednim državama. Ovaj podjednako sintezan i opsežan pregled djelo je skupine uvaženih stručnjaka – specijalista za pojedina razdoblja i problemska područja hrvatske -

Art in Europe 1945 — 1968 the Continent That the EU Does Not Know

Art in Europe 1945 Art in — 1968 The Continent EU Does that the Not Know 1968 The The Continent that the EU Does Not Know Art in Europe 1945 — 1968 Supplement to the exhibition catalogue Art in Europe 1945 – 1968. The Continent that the EU Does Not Know Phase 1: Phase 2: Phase 3: Trauma and Remembrance Abstraction The Crisis of Easel Painting Trauma and Remembrance Art Informel and Tachism – Material Painting – 33 Gestures of Abstraction The Painting as an Object 43 49 The Cold War 39 Arte Povera as an Artistic Guerilla Tactic 53 Phase 6: Phase 7: Phase 8: New Visions and Tendencies New Forms of Interactivity Action Art Kinetic, Optical, and Light Art – The Audience as Performer The Artist as Performer The Reality of Movement, 101 105 the Viewer, and Light 73 New Visions 81 Neo-Constructivism 85 New Tendencies 89 Cybernetics and Computer Art – From Design to Programming 94 Visionary Architecture 97 Art in Europe 1945 – 1968. The Continent that the EU Does Not Know Introduction Praga Magica PETER WEIBEL MICHAEL BIELICKY 5 29 Phase 4: Phase 5: The Destruction of the From Representation Means of Representation to Reality The Destruction of the Means Nouveau Réalisme – of Representation A Dialog with the Real Things 57 61 Pop Art in the East and West 68 Phase 9: Phase 10: Conceptual Art Media Art The Concept of Image as From Space-based Concept Script to Time-based Imagery 115 121 Art in Europe 1945 – 1968. The Continent that the EU Does Not Know ZKM_Atria 1+2 October 22, 2016 – January 29, 2017 4 At the initiative of the State Museum Exhibition Introduction Center ROSIZO and the Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts in Moscow, the institutions of the Center for Fine Arts Brussels (BOZAR), the Pushkin Museum, and ROSIZIO planned and organized the major exhibition Art in Europe 1945–1968 in collaboration with the ZKM | Center for Art and Media Karlsruhe. -

Modeli Interpretacije Djela Mladena Stilinovića

Modeli interpretacije djela Mladena Stilinovića Tomljenović, Anja Master's thesis / Diplomski rad 2020 Degree Grantor / Ustanova koja je dodijelila akademski / stručni stupanj: University of Zagreb, University of Zagreb, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences / Sveučilište u Zagrebu, Filozofski fakultet Permanent link / Trajna poveznica: https://urn.nsk.hr/urn:nbn:hr:131:773455 Rights / Prava: In copyright Download date / Datum preuzimanja: 2021-10-07 Repository / Repozitorij: ODRAZ - open repository of the University of Zagreb Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences SVEUČILIŠTE U ZAGREBU FILOZOFSKI FAKULTET Odsjek za povijest umjetnosti Diplomski rad MODELI INTERPRETACIJE DJELA MLADENA STILINOVIĆA Anja Tomljenović Mentorica: dr. sc. Lovorka Magaš Bilandžić, doc. ZAGREB, 2020. Temeljna dokumentacijska kartica Sveučilište u Zagrebu Diplomski rad Filozofski fakultet Odsjek za povijest umjetnosti Diplomski studij MODELI INTERPRETACIJE DJELA MLADENA STILINOVIĆA Models of Interpretation of Mladen Stilinović's Works Anja Tomljenović SAŽETAK U fokusu rada je analiza interpretativne recepcije umjetničkih radova Mladena Stilinovića na međunarodnim izložbama na Zapadu. Stilinović je jedan od najprisutnijih hrvatskih autora na svjetskoj umjetničkoj sceni. Dvaput je pozvan na Venecijansko bijenale i njegovi radovi predstavljeni su u brojnim uglednim svjetskim muzejima poput Muzeja moderne umjetnosti u New Yorku i Centra Georges Pompidou u Parizu. Pitanje interpretacije njegova rada postavlja se u širi kontekst nove geopolitičke podjele svijeta nakon 1989. godine te interesa Zapada za umjetnost i kulturu dotad „nepoznatih“ zemalja koje nisu dio dominantnog kanona. S obzirom na Stilinovićev umjetnički interes i propitivanje ideologije, politike i ekonomije, njegov opus zanimljivo je analizirati upravo iz rakursa zapadnjačke percepcije o umjetniku postjugoslavenskog prostora. Na primjeru međunarodne izložbene prakse nakon 1989. godine u radu se analizira zapadnjački pogled na Stilinovićeve najčešće izlagane radove. -

Tendencije 4 Tendencies 4 Zagreb, 1968--1969

• t4 tendencije 4 tendencies 4 zagreb, 1968--1969. zagreb, 1968-1969. kompjuteri i vizuelna istraživanja computers and visual research međunarodni kolokvij i izložba international colloquy and exhibition centar za kulturu i informacije centar za kulturu i informacije preradovićeva 5 preradovićeva 5 zagreb, 3-4, kolovoza 1968. zagreb august 3-4, 1968. kompjuteri i vizuelna istraživanja computers and visual research informativni seminar informativ-e seminar centar za kulturu i informacije centar za kulturu i informacije preradovićeva 5 preradovićeva 5 zagreb, 10-12 siječnja 1969. zagreb, january 10-12, 1969. kompjuteri i vizuelna istraživanja computers and visual research međunarodna izložba international exhibition galerija suvremene umjetnosti galerija suvremene umjetnosti ka tarinin trg 2 katarinin trg 2 zagreb, 5. svibnja - 30. kolovoza 1969. zagreb, may 5 - august 30, 1969. nove tendencije 4 new tendencies 4 međunarodna izložba international exhibition muzej za umjetnost i obrt muzej za umjetnost i obrt trg maršala tita 10 trg maršala tita 10 zagreb, 5. svibnja - 30. lipnja 1969. zagreb, may 5 - june 30, 1969. kompjuteri i vizuelna istraživanja computers and visual research međunarodni simpozij international symposium radničko sveučilište »rnoša pijade- radničko sveučilište »moša pijade« proleterskih brigada 68 proleterskih brigada 68 zagreb, 5-6. svibnja 1969. zagreb, may 5-6, 1969. typoezija typoezija međunarodna izložba international exhibition galerija studentskog centra galerija studentskog centra savska cesta 25 savska cesta 25 zagreb, 6. svibnja - 24. svibnja 1969. zagreb, may 6 - 24, 1969. ~zložba publikacija i knjiga exhibition of books and publications Internacionalna stalna izložba publikacija (ISlP) permanent international exhibition of publications (IST P) savska cesta 18 savska cesta 18 zagreb, 6. svibnja - 30. -

Ivana Bašičević Antić Moguća Putanja

SADRŽAJ CONTENT SMRT UETNOSTI, ŽIVELA UETNOST DEATH TO ART, LONG LIVE ART Ivana Bašičević Antić I B A Moguća putanja radikalnih umetničkih praksi SRT UETNOSTI. ŽIVELA UETNOST u našem regionu dgovor na pitanje šta je okupilo kustosko-selektorski tim 19.og Bijenala ...vodeći kriterijum bio je umetnosti u Pančevu, istovremeno je i definicija koncepta ovog Bijenala. iskrena vera umetnika Naime, okupila nas je ideja da se prošlost ne sme zaboraviti i odbaciti, Oiako je to, čini se, globalna težnja učesnika današnje umetničke scene. Mladih umet- SMRT UMETNOSTI ŽIVELA UMETNOST UMETNOSTI SMRT u snagu umetnosti i njenu vezu nika posebno. Šta je to u prošlosti vredno pamćenja, naravno, složeno je pitanje i naš je izbor samo jedan od niz mogućih odgovora. Različiti kriterijumi vodili bi ka sa životom uopšte, vera koja je sasvim različitim izborima, a naš je vodeći kriterijum bio iskrena vera umetnika pojedince vodila ka teškim u snagu umetnosti i njenu vezu sa životom uopšte, vera koja je pojedince vodila ka teškim borbama sa svojim okruženjem i vrlo često ka nezasluženom brisanju iz borbama sa svojim okruženjem istorijskih pregleda. Pri tom, što je zanimljivo, uglavnom iz lokalnih pregleda jer i vrlo često ka nezasluženom u očima svetske odnosno međunarodne umetničke scene upravo su te pojave bile 10 jedine vredne pamćenja. Tako nastale umetničke prakse označene su stalnim pre- 11 brisanju iz istorijskih pregleda. ispitivanjem značenja i smisla umetnosti, spajajući je sa životom jer u očima tih autora granice između ličnih života i domena umetnosti nikad nije bilo. Na osnovu Ljubomir Micić, 1925. navedenih kriterija napravili smo izbor umetnika savremene produkcije tragajući za onim autorima koji su u dijalogu sa dostignućima prethodnih generacija. -

The Year We Make Contact

The Year We Make Contact 20 Years of Media-Scape Dedicated to Pierre Schaeffer Exhibition of video, computer and sound installations, photography and holography, performances, screenings, concerts Zagreb, 8–29 October 2010 CURATORS AND ORGANIZERS Media- Scape exhibition (8–29 October 2010) and performances (8 and 9 October 2010): Ingeborg Fülepp and Heiko Daxl Curatorial and technical assistance: Iva Kovač and Martina Vrbanić Press: Iva Kovač Technical assistance: Mihael Pavlović Concerts and film programs (8 and 9O ctober 2010): Nikša Gligo, Seadeta Midžić, Daniel Teruggi, Dalibor Davidović (Jocelyne Tournet) Press: Bruno Bahunek Media facade screenings: Tihomir Milovac Special thanks to Ana Vuzdarić (guided tour), Luka Kedžo and Daniela Bušić (video documentation), and all the artists and friends who have contributed to the successful realization of the Media-Scape 2010 exhibition, performances and screenings I LN COL ABORATION WITH Croatian Association of Visual Artists, Zagreb / Hrvatsko društvo likovnih umjetnika (HDLU), Zagreb. Director: Gaella Gottwald Museum of Contemporary Art / Muzej suvremene umjetnost (MSU), Zagreb. Director: Snježana Pintarić PARTN ER EVENT I nternational conference: “Pierre Schaeffer: MediArt”, 6–7 October 2010, Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art / Muzej moderne i suvremene umjetnosti (MMSU), Rijeka. Director: Jerica Ziherl. Assistant: Vima Bartolić CONE F RENC INITIATORS AND COORDINATORS N ikša Gligo, Seadeta Midžić, Daniel Teruggi, Dalibor Davidović, Jerica Ziherl PULSE B I H RS Croatian Association