Finding the Maryland 400

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Fall Membership Meeting Saturday, October 22, 2016 – 6:00 P.M

THE REC RD Volume 111, No. 3 A Publication of the Historical Society of Charles County, Inc. October 2016 Mary Pat Berry, President Mary Ann Scott, Editor Annual Fall Membership Meeting Saturday, October 22, 2016 – 6:00 p.m. Durham Church Hall - Ironsides, Maryland Admiral Raphael Semmes and the C.S.S. Alabama presented by Dr. Charles P. Neimeyer Menu Roast pork, “a delicious variety of fall vegetables” to include carrot soufflé, rolls, tea, coffee, and fresh baked dessert $25.00 per person - Please R.s.v.p. no later than October 14, 2016 to Carol Donohue ~ 16401 Old Marshall Hall Road ~ Accokeek, MD 20607 The Correspondence of an Overlooked Founding Father: Daniel of St. Thomas Jenifer by Kevin Grote Continuation… This plan if generally adopted would put under your Excellency’s direction and command a regular and efficient force, on which you could constantly depend; it would save a great expence to these States in carriage, provisions, arms and accoutrements; it would conduce to reconcile the minds of the D aniel of St. Thomas Jenifer (first President of the Maryland Senate, people to the heavy charges of the War, when assured, they should be left at four year member of the Continental Congress, and a Signer of the United home to cultivate their lands, and reap the fruits of their industry; it would States Constitution) spent a lifetime in service to the people of Maryland, certainly tend to encrease our crops, and afford the means of maintaining and then took those skills, at the behest of his long-time good friend George a much greater regular Army than can be supported under frequent calls of Washington, to national issues, as the shortcomings of the Articles of the Militia; it would in some degree prevent those emigrations of our Men Confederation were threatening the early end of the American Experiment. -

"Fifth" Maryland at Guilford Courthouse: an Exercise in Historical Accuracy - L

HOME CMTE. SUBMISSIONS THE "FIFTH" MARYLAND AT GUILFORD COURTHOUSE: AN EXERCISE IN HISTORICAL ACCURACY - L. E. Babits, February 1988 Over the years, an error has gradually crept into the history of the Maryland Line. The error involves a case of mistaken regimental identity in which the Fifth Maryland is credited with participation in the battle of Guilford Courthouse at the expense of the Second Maryland.[1] When this error appeared in the Maryland Historical Magazine,[2] it seemed time to set the record straight. The various errors seem to originate with Mark Boatner. In his Encyclopedia of the American Revolution, Boatner, while describing the fight at Guilford Courthouse, states: As the 2/Gds prepared to attack without waiting for the three other regiments to arrive, Otho Williams, "charmed with the late demeanor of the first regiment (I Md), hastened toward the second (5th Md) expecting a similar display...". But the 5th Maryland was virtually a new regiment. "The sight of the scarlet and steel was too much for their nerves," says Ward.[3] In this paragraph Boatner demonstrates an ignorance of the actual command and organizational structure of Greene's Southern Army because he quotes from Ward's l94l work on the Delaware Line and Henry Lee's recollections of the war, both of which correctly identify the unit in question as the Second Maryland Regiment.[4] The writer of the Kerrenhappuch Turner article simply referred to Boatner's general reference on the Revolutionary War for the regimental designation.[5] Other writers have done -

'Deprived of Their Liberty'

'DEPRIVED OF THEIR LIBERTY': ENEMY PRISONERS AND THE CULTURE OF WAR IN REVOLUTIONARY AMERICA, 1775-1783 by Trenton Cole Jones A dissertation submitted to Johns Hopkins University in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Baltimore, Maryland June, 2014 © 2014 Trenton Cole Jones All Rights Reserved Abstract Deprived of Their Liberty explores Americans' changing conceptions of legitimate wartime violence by analyzing how the revolutionaries treated their captured enemies, and by asking what their treatment can tell us about the American Revolution more broadly. I suggest that at the commencement of conflict, the revolutionary leadership sought to contain the violence of war according to the prevailing customs of warfare in Europe. These rules of war—or to phrase it differently, the cultural norms of war— emphasized restricting the violence of war to the battlefield and treating enemy prisoners humanely. Only six years later, however, captured British soldiers and seamen, as well as civilian loyalists, languished on board noisome prison ships in Massachusetts and New York, in the lead mines of Connecticut, the jails of Pennsylvania, and the camps of Virginia and Maryland, where they were deprived of their liberty and often their lives by the very government purporting to defend those inalienable rights. My dissertation explores this curious, and heretofore largely unrecognized, transformation in the revolutionaries' conduct of war by looking at the experience of captivity in American hands. Throughout the dissertation, I suggest three principal factors to account for the escalation of violence during the war. From the onset of hostilities, the revolutionaries encountered an obstinate enemy that denied them the status of legitimate combatants, labeling them as rebels and traitors. -

The Linden Times

The Linden Times A bi-weekly newsletter for the members & friends of the Calvert County Historical Society – March 19, 2021 This edition of The Linden Times is four pages in celebration of The Maryland 400. No, the Maryland 400 is not a NASCAR race held in Maryland; rather it is about Maryland’s first and most distinguished Revolutionary soldiers. The Maryland 400, also called “The Old Line” , were members of the 1st Maryland Regiment who repeatedly charged a numerically superior British force during the The Maryland 400 at the Battle of Brooklyn Revolutionary War’s Battle of Long Island, NY. As the leading conflict after the signing of the Declaration of Independence, the fallen soldiers were the first to die as Americans defending their country, as opposed to colonial subjects rebelling against the monarchy. The Maryland 400 sustained very heavy casualties but allowed General Washington to successfully save the bulk of his nearly surrounded continental troops and evacuated them to Manhattan. This historic action is commemorated in the State of Maryland's nickname, “The Old Line State." The lineage for the Maryland Regiment can be traced to June 14, 1775, when military units were formed to protect the frontiers of western Maryland. In August of that year, another two companies assembled in Frederick, Maryland. They then marched 551 miles in 21 days to support General Washington’s efforts to drive the British out of Boston. Later, more Maryland militia companies, (armed with older, surplus British muskets and bayonets), were formed and then sent north to support Washington’s battles for New York City. -

Signers of the United States Declaration of Independence Table of Contents

SIGNERS OF THE UNITED STATES DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE 56 Men Who Risked It All Life, Family, Fortune, Health, Future Compiled by Bob Hampton First Edition - 2014 1 SIGNERS OF THE UNITED STATES DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTON Page Table of Contents………………………………………………………………...………………2 Overview………………………………………………………………………………...………..5 Painting by John Trumbull……………………………………………………………………...7 Summary of Aftermath……………………………………………….………………...……….8 Independence Day Quiz…………………………………………………….……...………...…11 NEW HAMPSHIRE Josiah Bartlett………………………………………………………………………………..…12 William Whipple..........................................................................................................................15 Matthew Thornton……………………………………………………………………...…........18 MASSACHUSETTS Samuel Adams………………………………………………………………………………..…21 John Adams………………………………………………………………………………..……25 John Hancock………………………………………………………………………………..….29 Robert Treat Paine………………………………………………………………………….….32 Elbridge Gerry……………………………………………………………………....…….……35 RHODE ISLAND Stephen Hopkins………………………………………………………………………….…….38 William Ellery……………………………………………………………………………….….41 CONNECTICUT Roger Sherman…………………………………………………………………………..……...45 Samuel Huntington…………………………………………………………………….……….48 William Williams……………………………………………………………………………….51 Oliver Wolcott…………………………………………………………………………….…….54 NEW YORK William Floyd………………………………………………………………………….………..57 Philip Livingston…………………………………………………………………………….….60 Francis Lewis…………………………………………………………………………....…..…..64 Lewis Morris………………………………………………………………………………….…67 -

George Washington Papers, Series 2, Letterbooks 1754-1799

George Washington Papers, Series 2, Letterbooks 1754-1799 To LUND WASHINGTON February 28, 1778. …If you should happen to draw a prize in the militia , I must provide a man, either there or here, in your room; as nothing but your having the charge of my business, and the entire confidence I repose in you, could make me tolerable easy from home for such a length of time as I have been, and am likely to be. This therefore leads me to say, that I hope no motive, however powerful, will induce you to leave my business, whilst I, in a manner, am banished from home; because I should be unhappy to see it in common hands. For this reason, altho' from accidents and misfortunes not to be averted by human foresight, I make little or nothing from my Estate, I am still willing to increase your wages, and make it worth your while to continue with me. To go on in the improvement of my Estate in the manner heretofore described to you, fulfilling my plans, and keeping my property together, are the principal objects I have in view during these troubles; and firmly believing that they will be accomplished under your management, as far as circumstances and acts of providence will allow, I feel quite easy under disappointments; which I should not do, if my business was in common hands, 38 liable to suspicions. I am, etc. 38. Extract in “Washington's Letter Book, No. 5.” Lund answered (March 18): “By your letter I should suppose you were apprehensive I intended to leave you. -

David Library of the American Revolution Guide to Microform Holdings

DAVID LIBRARY OF THE AMERICAN REVOLUTION GUIDE TO MICROFORM HOLDINGS Adams, Samuel (1722-1803). Papers, 1635-1826. 5 reels. Includes papers and correspondence of the Massachusetts patriot, organizer of resistance to British rule, signer of the Declaration of Independence, and Revolutionary statesman. Includes calendar on final reel. Originals are in the New York Public Library. [FILM 674] Adams, Dr. Samuel. Diaries, 1758-1819. 2 reels. Diaries, letters, and anatomy commonplace book of the Massachusetts physician who served in the Continental Artillery during the Revolution. Originals are in the New York Public Library. [FILM 380] Alexander, William (1726-1783). Selected papers, 1767-1782. 1 reel. William Alexander, also known as “Lord Sterling,” first served as colonel of the 1st NJ Regiment. In 1776 he was appointed brigadier general and took command of the defense of New York City as well as serving as an advisor to General Washington. He was promoted to major- general in 1777. Papers consist of correspondence, military orders and reports, and bulletins to the Continental Congress. Originals are in the New York Historical Society. [FILM 404] American Army (Continental, militia, volunteer). See: United States. National Archives. Compiled Service Records of Soldiers Who Served in the American Army During the Revolutionary War. United States. National Archives. General Index to the Compiled Military Service Records of Revolutionary War Soldiers. United States. National Archives. Records of the Adjutant General’s Office. United States. National Archives. Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty and Warrant Application Files. United States. National Archives. Revolutionary War Rolls. 1775-1783. American Periodicals Series I. 33 reels. Accompanied by a guide. -

Maryland Historical Trust STREET and NUMBER: 94 College Avenue CITY OR TOWN: STATE: Annapolis Maryland 24 MHT CH-5

MHT CH-5 Form 10-300 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR (July 1969) NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Maryland COUNTY: NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES Charles INVENTORY -NOMINATION FORM FOR NPS USE ONLY ENTRY NUMBER (Type all entries — complete applicable sections) TlBfr Habre de Venture -a, AND/OR HISTORIC: Habre-de-Venture, Habredeventure STREET ANDNUMBER: Rose Hill Road CITY OR TOWN: Port Tobacco CODE COUNTY: Maryland 24 Charles m.7 CATEGORY ACCESSIBLE wo OWNERSHIP STATUS (Check One) TO THE PUBLIC Z D District .g] Building D Public Public Acquisition: 53 Occupied Yes: Restricted o D Site n Structure SI Private [| In Process I| Unoccupied Unrestricted D Object n Both | | Being Considered Q Preservation work h- in progress No u PRESEN T USE (Check One or More as Appropriate) EQ Agricultural Q Government l~~l Transportation |~1 Comments | | Commercial I | Industrial JT] Private Residence n Other (Specify) h- I | Educational O Military [~~1 Religious II Museum co I I Entertainment O Scientific OWNER'S NAME: JS 2 Mrs. Peter Vischer UJ STREET AND NUMBER: LLJ Rose Hill Road CO CITY OR TOWN: CODE Port Tobacco Maryland 24 COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC: Hall of Records STREET AND NUMBER: St. John's College Campus, College Avenue H CITY OR TOWN: fl> in Annapolis Maicyland 24 TITLE OF SURVEY: SEE CONT'INUOTION '"S'HEEi1" Maryland Register of Historic Sites and Landmarks DATE OF SURVEY: 1968 Federal State | | County D Local DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS: Maryland Historical Trust STREET AND NUMBER: 94 College Avenue CITY OR TOWN: STATE: Annapolis Maryland 24 MHT CH-5 (Check One) Good Q Fair CD Deteriorated Q Ruins CD Unexposed CONpTflOR (Check One; (Check One) Altered C8 Unaltered Moved E3 Original Site DESCRIBE TH,E fJfiESENT AND ORIGINAL (if fcnoivnj PHYSICAL APPEARANCE "r7-^.....-..;-<\ \> ^dillS^^'re de Venture is located on the west side of Rose Hill Road, north, of "Rose Hill," south of the intersection of Rose Hill Road, Bumpy Oak Road, Marshalls Corner Road and Maryland Route 225, about three miles west of La Plata, Maryland. -

Link.Net Chancellor General Davis Lee Wright, Esq., P.O

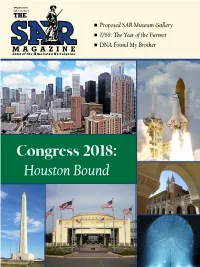

SPRING 2018 Vol. 112, No. 4 n Proposed SAR Museum Gallery n 1768: The Year of the Farmer n DNA Found My Brother Congress 2018: Houston Bound SPRING 2018 Vol. 112, No. 4 6 16 6 2018 Congress to Convene 10 America’s Heritage and the 22 Newly Acquired Letters in Houston SAR Library Reveal More About the Maryland 400 7 Amendment Proposal/ 11 The Proposed SAR Museum Leadership Medical Committee Gallery 24 State Society & Chapter News 8 Nominating Committee Report/Butler Awarded 16 250th Series: 1768—The Year 38 In Our Memory/ Medal of Honor of the Farmer New Members 9 Newsletter Competitions 20 DNA Found My Brother 47 When You Are Traveling THE SAR MAGAZINE (ISSN 0161-0511) is published quarterly (February, May, August, November) and copyrighted by the National Society of the Sons of the American Revolution, 809 West Main Street, Louisville, KY 40202. Periodicals postage paid at Louisville, KY and additional mailing offices. Membership dues include The SAR Magazine. Subscription rate $10 for four consecutive issues. Single copies $3 with checks payable to “Treasurer General, NSSAR” mailed to the HQ in Louisville. Products and services advertised do not carry NSSAR endorsement. The National Society reserves the right to reject content of any copy. Send all news matter to Editor; send the following to NSSAR Headquarters: address changes, election of officers, new members, member deaths. Postmaster: Send address changes to The SAR Magazine, 809 West Main Street, Louisville, KY 40202. PUBLISHER: STAFF DIRECTORY President General Larry T. Guzy As indicated below, staff members have an email address and an extension number of the automated 4531 Paper Mill Road, SE telephone system to simplify reaching them. -

Maryland Historical Magazine, 1946, Volume 41, Issue No. 4

MHRYMnD CWAQAZIU^j MARYLAND HISTORICAL SOCIETY BALTIMORE DECEMBER • 1946 t. IN 1900 Hutzler Brothers Co. annexed the building at 210 N. Howard Street. Most of the additional space was used for the expansion of existing de- partments, but a new shoe shop was installed on the third floor. It is interesting to note that the shoe department has now returned to its original location ... in a greatly expanded form. HUTZLER BPOTHERSe N\S/Vsc5S8M-lW MARYLAND HISTORICAL MAGAZINE A Quarterly Volume XLI DECEMBER, 1946 Number 4 BALTIMORE AND THE CRISIS OF 1861 Introduction by CHARLES MCHENRY HOWARD » HE following letters, copies of letters, and other documents are from the papers of General Isaac Ridgeway Trimble (b. 1805, d. 1888). They are confined to a brief period of great excitement in Baltimore, viz, after the riot of April 19, 1861, when Federal troops were attacked by the mob while being marched through the City streets, up to May 13th of that year, when General Butler, with a large body of troops occupied Federal Hill, after which Baltimore was substantially under control of the 1 Some months before his death in 1942 the late Charles McHenry Howard (a grandson of Charles Howard, president of the Board of Police in 1861) placed the papers here printed in the Editor's hands for examination, and offered to write an introduction if the Committee on Publications found them acceptable for the Magazine. Owing to the extraordinary events related and the revelation of an episode unknown in Baltimore history, Mr. Howard's proposal was promptly accepted. -

Maryland D C Virginia

130522ngx Silver Spring EASTERN AVE schematic map not to scale TAKOMA MO CHEVY CHASE PARK WASHINGTON, S4 S2 DC DC VA PG Metrobus S9 System Map September 2016 Chestnut St 16th St Oregon Ave Oregon 79 70 Consult other Metrobus System Maps for service in Virginia, Prince George’s County, MD, and ALASKA AVE Montgomery County, MD. This map provides an overview of bus and rail Knollwood Piney MARYLAND Western Ave services. For detailed information on each route, Lindsey Dr Branch Rd NEW HAMPSHIRE AVE M4 E6 S2 S9 Takoma please refer to individual schedules. Utah Ave Butternut St S4 52 Eastern E6 Ave wmata.com 202.637.7000 Aspen St 53 62 K2 K6 BARNABY 54 63 1 Rock K9 Designed by CHK America WOODS 11 Creek Broad Branch L8 Rd Park R1 WEST 14th St 5th St Blair Rd Kansas Ave F1 R2 HYATTSVILLE GEORGIA AVE BRIGHTWOOD EASTERNF2 Chillum Rd Nebraska Ave L1 L2 AVE F6 Ave K2 S1 30TH PL MISSOURI AVE E6 MCKINLEY ST MILITARY RD KENNEDY ST Sargent BETHESDA RIGGS RD E4 Rd Yellow Line to/from Nicholson St rush Carter Barron Kennedy St Greenbelt during E4 peak hours Military Rd Ampitheatre Chillum Pl E4 WESTERN AVE Colorado F1 Connecticut Ave 5th St 52 79 70 Galloway St F2 53 Friendship Heights M4 60 54 Lasalle Rd MOUNT 29 Massachusetts Ave 30N 30S Gallatin St Fort 23 F6 Gallatin St RHODE ISLAND AVE Sargent Rd Sargent 31 33 Totten SOUTH E2 RAINIER New Hampshire Ave North Capitol St DAKOTA AVE 83 37 62 Nebraska Ave Queens Chapel Rd 86 N2 H2 H4 63 64 16TH ST DC 14TH ST Western Ave H3 L1 Hawaii R4 Westbard Ave Ave SOMERSET L2 N4 Tenleytown-AU S1 GEORGIA AVE Providence -

Attendees at George Washington's Resignation of His Commission Old Senate Chamber, Maryland State House, December 23

Attendees at George Washington’s Resignation of his Commission Old Senate Chamber, Maryland State House, December 23, 1783 Compiled by the Maryland State Archives, February 2009 Known attendees: George Washington Thomas Mifflin, President of the Congress Charles Thomson, Secretary of the Congress Other known attendees: Members of the Governor and Council of Maryland. Specific members are not identified; full membership listed below Members of the government of the City of Annapolis. Specific members are not identified; full membership listed below Henry Harford, former Proprietor of Maryland Sir Robert Eden, former governor Those who attended who wrote about the ceremony in some detail: Dr. James McHenry, Congressman and former aide to Washington Mollie Ridout Dr. James Tilton, Congressman There was a “gallery full of ladies” (per Mollie Ridout), most of whom are unknown Members of the Maryland General Assembly The General Assembly was in Session on December 23, and both houses convened in the State House on December 22 and on December 23. It is difficult to identify specific individuals who were in the Senate Chamber GENERAL ASSEMBLY OF 1783 William Paca, governor November 3-December 26, 1783 SENATE WESTERN James McHenry EASTERN Edward Lloyd SHORE SHORE George Plater Daniel Carroll, Matthew John Cadwalader (E, president ' Tilghman Dcl) Thomas Stone Richard Barnes ' (DNS, R) Robert Goldsborough (DNS) (E, Charles Carroll of Benedict Edward Hall John Henry DNS) Carrollton, Samuel Hughes William Hindman William Perry (E) president ' John Smith Josiah Polk (DNS) HOUSE OF DELEGATES ST MARY'S John Dent, of John CECIL Nathan Hammond William Somerville BALTIMORE Archibald Job Thomas Ogle John DeButts Thomas Cockey Deye, Samuel Miller HARFORD Edmund Plowden speaker William Rowland Benjamin Bradford Norris Philip Key Charles Ridgely, of Benjamin Brevard John Love William KENT John Stevenson ANNAPOLIS John Taylor (DNS) Peregrine Lethrbury Charles Ridgely Allen Quynn Ignatius Wheeler, Jr.