Immediate Life Support PRE -Course Handbook

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ABCDE Approach

The ABCDE and SAMPLE History Approach Basic Emergency Care Course Objectives • List the hazards that must be considered when approaching an ill or injured person • List the elements to approaching an ill or injured person safely • List the components of the systematic ABCDE approach to emergency patients • Assess an airway • Explain when to use airway devices • Explain when advanced airway management is needed • Assess breathing • Explain when to assist breathing • Assess fluid status (circulation) • Provide appropriate fluid resuscitation • Describe the critical ABCDE actions • List the elements of a SAMPLE history • Perform a relevant SAMPLE history. Essential skills • Assessing ABCDE • Needle-decompression for tension • Cervical spine immobilization pneumothorax • • Full spine immobilization Three-sided dressing for chest wound • • Head-tilt and chin-life/jaw thrust Intravenous (IV) line placement • • Airway suctioning IV fluid resuscitation • • Management of choking Direct pressure/ deep wound packing for haemorrhage control • Recovery position • Tourniquet for haemorrhage control • Nasopharyngeal (NPA) and oropharyngeal • airway (OPA) placement Pelvic binding • • Bag-valve-mask ventilation Wound management • • Skin pinch test Fracture immobilization • • AVPU (alert, voice, pain, unresponsive) Snake bite management assessment • Glucose administration Why the ABCDE approach? • Approach every patient in a systematic way • Recognize life-threatening conditions early • DO most critical interventions first - fix problems before moving on -

TCCC CLS Skill Instructions Mod 7 25 JAN 20

MODULE 07: AIRWAY MANAGEMENT IN TFC SKILL INSTRUCTIONS 25 JAN 2020 COMBAT LIFESAVER (CLS) TACTICAL COMBAT CASUALTY CARE SKILL INSTRUCTIONS HEAD-TILT/CHIN-LIFT INSTRUCTION TASK: Open an airway using the head-tilt/chin-lift maneuver CONDITION: Given a simulated scenario where a casualty and responder are in combat gear and the casualty is unconscious without a patent airway STANDARD: EffeCtively open the airway by performing the head-tilt/chin-lift maneuver following all steps and measures correctly without Causing further harm to the Casualty EQUIPMENT: N/A PERFORMANCE MEASURES: step-by-step instructions NOTE: Do not use if a spinal or neck injury is suspected. 01 Roll the Casualty onto their back, if necessary, and place them on a hard, flat surface. 02 Kneel at the level of the Casualty’s shoulders. Position yourself at the side of the Casualty. 03 Open the mouth and looK for visible airway obstruCtions (e.g., laCerations, obstructions, broken teeth, burns, or swelling or other debris, such as vomit). NOTE: If foreign material or vomit is in the mouth, remove it as quiCKly as possible. NOTE: Do not perform a blind finger sweep. 04 PlaCe one hand on the Casualty's forehead and apply firm, backward pressure with the palm to tilt the head back. 05 PlaCe the fingertips of the other hand under the bony part of the lower jaw and lift, bringing the Chin forward. NOTE: Do not use the thumb to lift the chin. 06 While maintaining the open airway position, place an ear over the casualty's mouth and nose, looking toward the chest and stomaCh. -

Scope of Practice Statements

Scope of Practice Statements Emergency Medical Services Authority California Health and Human Services Agency EMSA # 300 November 2017 HOWARD BACKER, MD, MPH, FACEP DIRECTOR DANIEL R. SMILEY CHIEF DEPUTY DIRECTOR SEAN TRASK DIVISION CHIEF EMSA # 300 Released November 2017 EMSA #300 • Page 1 Table of Contents Introduction ........................................................................................................................................... 4 The EMS Authority ................................................................................................................................ 4 Local EMS Agencies ............................................................................................................................. 4 California EMS Personnel Levels .......................................................................................................... 4 Reading the Scope of Practice Pages .................................................................................................. 5 Airway and Breathing ............................................................................................................................ 6 Airway Suctioning .............................................................................................................................. 7 Automatic Transport Ventilator .......................................................................................................... 8 Bag Valve Mask – BVM .................................................................................................................... -

Airway Administration Luke Koester AT, ATC, EMT

Airway Administration Luke Koester AT, ATC, EMT The primary function of an airway adjunct is to prevent obstruction of the upper airway by the tongue and allow the passage of air and oxygen to the lungs Nasopharyngeal Airways (NPA) -used in an unresponsive patient or a patient with an altered level of consciousness who has an intact gag reflex and is not able to maintain their airway spontaneously -patients with AMS or who have just had a seizure may also benefit from a NPA Indications Contraindications 1. semiconscious or unconscious patients with an 1. Severe head injury with blood draining from the nose intact gag reflex 2. History of fractured nasal bone 2. patients who otherwise will not tolerate an OPA *If the NPA is accidentally pushed through a hole caused by a fracture of the base of the skull (cribiform plate), it may penetrate into the brain -Inserting a Nasopharyngeal Airway 1. Size the airway by measuring from the tip of the nose to the patient’s earlobe 2. Coat the tip with a water-soluble lubricant 3. Insert the NPA into the right nare with the bevel facing the septum a. If there is trauma to the right nare, invert the NPA so the bevel is facing the septum and insert into the left nare 4. Advance the airway until the flange rests against the nostril a. If using the left nare, advance the NPA until resistance is met, then rotate the NPA 180 degrees into position until the flange rests against the nostril Oropharyngeal Airways (OPA) -used to keep the tongue from blocking the upper airway -makes it easier to suction the oropharynx if necessary Indications Contraindications 1. -

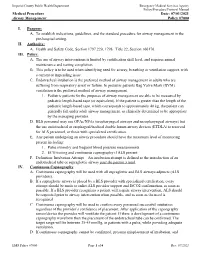

07/01/2021 Airway Management Policy #7000 I. Purpose

Imperial County Public Health Department Emergency Medical Services Agency Policy/Procedure/Protocol Manual Medical Procedure Date: 07/01/2021 Airway Management Policy #7000 I. Purpose: A. To establish indications, guidelines, and the standard procedure for airway management in the pre-hospital setting. II. Authority: A. Health and Safety Code, Section 1797.220, 1798. Title 22, Section 100170. III. Policy: A. The use of airway interventions is limited by certification skill level, and requires annual maintenance and testing completion. B. This policy is to be used when identifying need for airway, breathing or ventilation support, with a current or impending issue. C. Endotracheal intubation is the preferred method of airway management in adults who are suffering from respiratory arrest or failure. In pediatric patients Bag Valve Mask (BVM) ventilation is the preferred method of airway management. 1. Pediatric patients for the purposes of airway management are able to be measured by pediatric length-based tape (or equivalent). If the patient is greater than the length of the pediatric length-based tape, which corresponds to approximately 40 kg, the patient can generally fall under adult airway management, as clinically determined to be appropriate by the managing provider. D. BLS personnel may use OPAs/NPAs (oropharyngeal airways and nasopharyngeal airways) but the use endotracheal or esophageal/tracheal double lumen airway devices (ETDLA) is reserved for ALS personnel, or those with specialized certification. E. Any patient undergoing an airway procedure should have the maximum level of monitoring present including: 1. Pulse oximetry and frequent blood pressure measurements 2. ECG tracing and continuous capnography if ALS present F. -

Airway Management Milwaukee Challenges in Airway Patency

8/22/2014 Airway Management Does this patient need an emergent airway? Milwaukee Challenges in airway patency Tongue Blood Dental Trauma Vomit Distorted Landmarks Reflex Jaw Spasm C-Spine Injury 1 8/22/2014 Immediate Assessment Parameters Adequacy of current ventilation Patency of airway Duration of hypoventilation Need for paralyzing agents C-Spine injury Equipment and Experience Airway Stabilization Techniques Positioning to relieve tongue obstruction Chin Lift or Jaw Thrust (No Neck lift, or extension!!) Elevated head position EAC to sternal notch Elevate with sheets or blanket Nasopharyngeal Airway Prevent tongue from obstructing airway Frees the operator to do other things Insertion technique simple 2 8/22/2014 Nasal Intubation? LaFort III Fracture I wouldn’t Suboptimal intubation Oropharyngeal Airway Prevents tongue from obstructing airway Insert inverted along hard palate then twist Size by corner of mouth to EAC 3 8/22/2014 Bag-Valve-Mask May be the most important airway skill Tight Mask seal is mandatory Two man technique best Incidence of impossible BVM? Cyclists are ideal patients!! Gastric distention… overly concerned Oxygenation Technique Slow 1-2 second breaths TV goal 450cc, every 5 seconds, 12BPM Cricoid pressure? Role for paralytics? Oxygen flow NODESAT technique NC @15LPM Place a nasal cannula too? Definitive Airway Indications Coma and lack of gag reflex (GCS<8) Severe facial trauma Aspiration Risk Expanding neck hematoma, edema or stridor Impending respiratory failure Hypoxia or inability to adequately ventilate with -

The Nasopharyngeal Airway: Dispelling Myths and Establishing the Facts

394 REVIEW Emerg Med J: first published as 10.1136/emj.2004.021402 on 23 May 2005. Downloaded from The nasopharyngeal airway: dispelling myths and establishing the facts K Roberts, H Whalley, A Bleetman ............................................................................................................................... Emerg Med J 2005;22:394–396. doi: 10.1136/emj.2004.021402 The nasopharyngeal airway (NPA) is a simple airway trials. Level II, Strong evidence from at least one properly designed randomised controlled adjunct used by various healthcare professionals. It has trial of appropriate size. Level III, Evidence from some advantages over the oropharyngeal airway (OPA) well-designed trials such as non-randomised but despite this it appears to be used less frequently. This trials, cohort studies, time series, or matched case-controlled studies. Level IV, Evidence from may be due to fears over intracranial placement in cases of well-designed non-experimental studies from possible basal skull fracture. This fear, promulgated by more than one centre or research group. Level training, is based solely on two single case reports and V, Opinions of respected authorities, based on clinical evidence, descriptive studies or reports of relative risk needs to be put into clinical context.Widely expert committees.) taught methods of sizing NPAs are based upon the width of the patient’s nostril or little finger, MRI data demonstrate DISCUSSION that these methods are inaccurate. Ideal NPA length Sizing an NPA measured at nasal endoscopy correlates with subject Widely taught34 methods of sizing an NPA include comparing an NPA to the width of the height, this is independent of subject sex, and is a far more patients little finger or nares. -

Basic Airway Management & Decision Making

Roberts: Clinical Procedures in Emergency Medicine, 5th ed. CHAPTER 3 – Basic Airway Management and Decision-Making Robert F. Reardon, Phillip E. Mason, Joseph E. Clinton Over the last few decades, several important changes have occurred in emergency airway management. Bag-mask ventilation has been supplemented by intermediate, or backup, ventilation devices like the laryngeal mask airway (LMA), the Combitube, and the laryngeal tube. These have become important devices for the initial resuscitation of apneic patients and for rescue ventilation when intubation fails.[1] Noninvasive positive-pressure ventilation (NPPV) is now used in place of tracheal intubation in some critically ill patients. Despite these advances, basic techniques such as opening the airway, oxygenation, and bag-mask ventilation remain the cornerstones of good emergency airway management. [2] [3] Airway maintenance without endotracheal intubation is one of the most important emergency [4] airway management techniques to keep patients alive until a definitive airway can be established. This chapter describes basic airway skills including opening the airway, O2 therapy, NPPV, bag-mask ventilation, and intermediate ventilation devices. Because of the complexity of these skills and decisions, providers should develop a simple, organized approach to emergency airway management, being cognizant that when a specific intervention has failed, it is time to move rapidly to a different approach. Developing a simple preconceived algorithm that employs proven techniques and is applicable to a broad range of clinical scenarios will help providers manage difficult, anxiety-provoking emergency airways. THE CHALLENGE OF EMERGENCY AIRWAY MANAGEMENT Although other specialists are sometimes available, most emergency airways are managed by emergency clinicians.[5] Airway management in the emergency department (ED) is much different from airway management in the controlled setting of the operating room. -

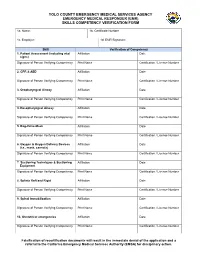

EMT-I Skills Verification Form

YOLO COUNTY EMERGENCY MEDICAL SERVICES AGENCY EMERGENCY MEDICAL RESPONDER (EMR) SKILLS COMPETENCY VERIFICATION FORM 1a. Name: 1b. Certificate Number 1c. Employer: 1d. EMR Signature: Skill Verification of Competency 1. Patient Assessment (including vital Affiliation Date signs) Signature of Person Verifying Competency Print Name Certification / License Number 2. CPR & AED Affiliation Date Signature of Person Verifying Competency Print Name Certification / License Number 3. Oropharyngeal Airway Affiliation Date Signature of Person Verifying Competency Print Name Certification / License Number 4. Nasopharyngeal Airway Affiliation Date Signature of Person Verifying Competency Print Name Certification / License Number 5. Bag-Valve-Mask Affiliation Date Signature of Person Verifying Competency Print Name Certification / License Number 6. Oxygen & Oxygen Delivery Devices Affiliation Date (i.e., mask, cannula) Signature of Person Verifying Competency Print Name Certification / License Number 7. Suctioning Techniques & Suctioning Affiliation Date Equipment Signature of Person Verifying Competency Print Name Certification / License Number 8. Splints Soft and Rigid Affiliation Date Signature of Person Verifying Competency Print Name Certification / License Number 9. Spinal Immobilization Affiliation Date Signature of Person Verifying Competency Print Name Certification / License Number 10. Obstetrical emergencies Affiliation Date Signature of Person Verifying Competency Print Name Certification / License Number Falsification of recertification documents will result in the immediate denial of the application and a referral to the California Emergency Medical Services Authority (EMSA) for disciplinary action. INSTRUCTIONS FOR COMPLETION OF EMR SKILLS COMPETENCY VERIFICATION FORM A completed EMR Skills Verification Form is required to be submitted prior to issuance of a certification card for candidates who are recertifying or who were previously certified as a First Responder. -

Airway Management

AIRWAY MANAGEMENT Angkana Lurngnateetape, MD. Department of Anesthesiology Siriraj Hospital Perhaps the most important responsibility of the anesthesiologist is “management of the patient’s airway” Miller RD’s Anesthesia 2000 Barash PG, Cullen BF, Stoelting RK’s Clinical Anesthesia 2001 What should we know about “airway management”? ● Airway anatomy and function ● Evaluation of airway ● Clinical management of the airway - Maintenance and ventilation - Intubation and extubation - Difficult airway management Airway anatomy The term “airway” refers to the upper airway, consisting of ● Nasal and oral cavities ● Pharynx ● Larynx ● Trachea ● Principle bronchi Anatomy of upper airway Larynx in laryngoscopic view Nerves V1 V2 V3 IX Vagus nerve • Superior laryngeal n – External br (Motor) • cricothyroid m SL – Internal br (Sensory) • area above cord • Recurrent laryngeal n - Motor br • intrinsic m RL – Sensory br • area below cord Evaluation of the airway ● History ● Physical examination ● Special investigation Evaluation of the airway “History” ● Previous history of difficult airway ● Airway-related untoward events ● Airway-related symptoms/diseases Evaluation of the airway Physical examination ● Ease of open airway and maintenance ● Ease of tracheal intubation ● Teeth ● Neck movement ● Intubation hazards ● Signs of airway distress Evaluation of the airway Anatomic characteristics associated with difficult airway management ● Short muscular neck ● Receding mandible ● Protruding maxillary incisors ● Long high-arched palate ● Inability to visualize -

The Efficiency of Bag-Valve Mask Ventilations by Medical First Responders and Basic Emergency Medical Technicians

California State University, San Bernardino CSUSB ScholarWorks Theses Digitization Project John M. Pfau Library 2003 The efficiency of bag-valve mask ventilations by medical first responders and basic emergency medical technicians John Vincent Commander Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project Part of the Vocational Education Commons Recommended Citation Commander, John Vincent, "The efficiency of bag-valve mask ventilations by medical first responders and basic emergency medical technicians" (2003). Theses Digitization Project. 2310. https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project/2310 This Project is brought to you for free and open access by the John M. Pfau Library at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses Digitization Project by an authorized administrator of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE EFFICIENCY OF BAG-VALVE MASK VENTILATIONS BY MEDICAL FIRST RESPONDERS AND BASIC EMERGENCY MEDICAL TECHNICIANS A Project Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in Education: Career and Technical Education by John Vincent Commander September 2003 THE EFFICIENCY OF BAG-VALVE MASK VENTILATIONS BY MEDICAL FIRST RESPONDERS AND BASIC EMERGENCY MEDICAL TECHNICIANS A Project Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino by John Vincent Commander September 2003 Approved by: © 2003 John Vincent Commander ABSTRACT• Bag-valve mask (BVM) ventilation maintains a patient's oxygenation and ventilation until a more definitive artificial airway can be established. In the prehospital setting of a traffic collision-or • medical aid scene this is performed by an Emergency Medical Technician or medical first responder. -

New Mexico Emergency Medical Services Guidelines Procedures

NEW MEXICO EMERGENCY MEDICAL SERVICES GUIDELINES PROCEDURES FIRST RESPONDER EMT- BASIC EMT- INTERMEDIATE (EMT-I) EMT-PARAMEDIC Updated September 2018 TABLE OF CONTENTS Contents ACUPRESSURE ....................................................................................................................................... 1 AIRWAY MANAGEMENT ......................................................................................................................... 2 GENERAL GUIDELINES ...................................................................................................................... 2 OROPHARYNGEAL SUCTIONING ...................................................................................................... 3 ENDOTRACHEAL SUCTIONING ......................................................................................................... 4 OROPHARYNGEAL AIRWAY .............................................................................................................. 6 NASOPHARANGEAL AIRWAY ............................................................................................................ 7 COMBITUBE® ...................................................................................................................................... 8 LARYNGEAL and SUPRAGLOTTIC AIRWAY DEVICES ................................................................... 11 KING AIRWAY ................................................................................................................................................................