Case 2:15-Cv-02246-SJF-ARL Document 20 Filed 04/29/15 Page 1 of 26 Pageid #: 241

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

15.0 Appendices

15.0 APPENDICES 15.1 APPENDIX A: STATE PERMIT REQUIREMENTS States have varying requirements for summer flounder permits, as summarized below (information as of April 2017). Massachusetts All persons who land and sell finfish in Massachusetts must have a commercial fishing permit from the Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries (MADMF) and must sell only to permitted Massachusetts dealers. A limited entry summer flounder (fluke) permit endorsement, in addition to a Massachusetts commercial fishing permit, is required for any individual and/or vessel to commercially fish for summer flounder within the state waters of Massachusetts, or to harvest, process, or land any summer flounder for commercial purposes in Massachusetts. This endorsement is limited entry due to a moratorium on new fluke endorsements instated in 1999 to address a substantial increase in participation and landings. The fluke endorsement must be renewed annually. MADMF policy has largely been against transfer of summer flounder endorsements, in order to maintain the moratorium’s effectiveness in reducing the total number of endorsements. However, MADMF allows endorsement transfers between immediate family members (provided they meet the existing eligibility criteria) on a one-time basis, after which the endorsement becomes non- transferable. In addition, inshore trawl fishermen who sell their businesses (i.e., vessels, permits, etc.) may transfer a summer flounder endorsement if the other permits are active as inshore trawling could result in excessive summer flounder discards otherwise. For the offshore fishery, transfer of the summer flounder endorsement to the new permit holder is allowed when vessels and federal permits are sold. Rhode Island A Rhode Island (RI) commercial fishing license with a restricted finfish endorsement is required to take summer flounder for commercial purposes from Rhode Island waters. -

Meeting Planner's Guide

DISCOVER LONG ISLAND NEW YORK Hilton Long Island/Huntington is the Ideal Choice for Your Next Business or Social Function Our hotel can accommodate a variety of meetings, conferences and trade shows, as well as social events such as bar/bat mitzvahs and weddings. Also offering convenient access to the Long Island Rail Road, Long Island Expressway and New York City. 2019/2020 MEETING PLANNER’S GUIDE LONG ISLAND MEETING PLANNER’S GUIDE 2019/2020 AT A GLANCE • Over 26,000ft2 of flexible meeting space, including 18 • Fitness Center with the latest cardio and strength meeting rooms, two-floor Savoy Ballroom and Grand Ballroom training equipment • Located on the 110 Corridor near several shops and • Masterson’s open for breakfast, lunch and dinner restaurants, as well as easy access to all major highways • Atrium Lounge • Large indoor pool, seasonal outdoor pool, whirlpool, tennis, • Sound Brew basketball and volleyball courts • Nanking — The premier choice for Indian, Chinese and Thai Cuisine MEETINGS & EVENTS With incredible amenities and space, your next event is guaranteed to be a success. We can accommodate trade shows, sales presentations, board meetings and employee receptions. For larger affairs such as award shows, weddings and A LONG ISLAND BUSINESS NEWS PUBLICATION bar/bat mitzvahs, we offer our Grand Ballroom or two-floor Savoy Ballroom. Additionally, all special events receive our exceptional catering services. RECENTLY RENOVATED | BEACHFRONT BALLROOMS | GATSBY-STYLE GATHERINGS 631-845-1000 598 Broadhollow Rd., Melville, NY 11747 WWW.HILTONLONGISLAND.COM A LONG ISLAND BUSINESS NEWS PUBLICATION DISCOVER LONG ISLAND NEW YORK Hilton Long Island/Huntington is the Ideal Choice for Your Next Business or Social Function Our hotel can accommodate a variety of meetings, conferences and trade shows, as well as social events such as bar/bat mitzvahs and weddings. -

Technical Report for More Details on the Definition of Direct and Indirect Impacts1 and the Study Methodology

TABLE OF CONTENTS NEW YORK STATEWIDE AIRPORT ECONOMIC IMPACTS STUDY EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................................... i 1. STUDY CONTEXT: NATIONAL AVIATION INDUSTRY & ECONOMIC FACTORS.........................................................................................................3 1.1 Impacts of the Global Economic Recession on Aviation in New York ..................3 1.2 Review of Other Economic Impact Studies .............................................................9 1.3 Activity at New York’s Commercial Service and GA Airports ............................11 1.4 Air Cargo’s Role in New York’s Economy ...........................................................17 1.5 Strategies for Revenue Generation and Increased Airport Economic Output .......20 1.6 NextGen Implementation and Anticipated Benefits in New York ........................33 2. STATEWIDE ECONOMIC IMPACT OF AVIATION ....................................................36 2.1 Job Impacts ............................................................................................................36 2.2 Income Impacts ......................................................................................................42 2.3 Output Impacts .......................................................................................................47 2.4 State & Local Tax Revenue Impacts .....................................................................52 2.5 Local Economic Impact .........................................................................................55 -

Town of East Hampton Airport Economic Analysis +

1. TOWN OF EAST HAMPTON AIRPORT ECONOMIC ANALYSIS Town of East Hampton New York + February 2002 BAST HAMPTON AIRPORT ECONOMIC ANALYSIS February r 2002 Prepared for Town of East HamPton, NY a planning grant from the Federal Aviation Adminisiration ement Act of 1982 and the New York Department of i as developed with the airport sponsor and do not necessarily k State. Acceptance of this report by the FAA and NYSDOT York State to participate in any does not in any way constitute a commitment on the part of the United States or New environmentally acceptable in development depicted t¡eie¡", nor does it indicate ftrat ttte proposed development is accordance with applicable public laws. Prepared by McFarland-Johnson, Inc. 49 Court Street Binghamton, New York 13902 607',123-9421 In Association With: R. A. Wiedemann & Associates,Inc. and Shumaker Consulting Engineering P.C. PO Box 621 and Land SwveYing, Georgetown,KY 40324 320 NoIth Jensen Road 13851 502 535-6570 Vestal, NY 607 798-8081 TABLE OF COruTENTS I INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 Study Issues 1 1.2 Objectives and Desired End Products J 1.3 Report Outline . 4 2. BACKGROUNDANDMANAGEMENTSTRUCTURE 5 2.1 Historical Mission of the Aþort 5 2.2 Historical Performance Meeting the Mission . 6 2.3 Aþort Management Structure 6 J EXISTING AIRPORT CHARACTERISTICS 7 3.1 Existing Activity and Facilities . 7 3.2 Future Airport Land Use l3 3.3 MarketAnalysis... 20 4. BASELINE FINANCIAI AND ECONOMIC OUTLOOK 25 4.1 Historical Revenues and Expenses 25 4.2 Baseline Forecast of Revenues & Expenses . 28 5. -

Fly Neighborly Program Faa “Throgs Route” Issues

1 FLY NEIGHBORLY PROGRAM FAA “THROGS ROUTE” ISSUES Eastern Region Helicopter Council - New York Community Aviation Roundtable - LGA Committee - 25 JAN 2018 ERHC - SINCE 1977 2 ▸ Active community outreach program to address concerns of residents, relating to helicopter and heliport issues. ▸ Extensive communications network for all members concerning safety issues, Airspace Flight Restrictions, noise abatement issues, and regulatory issues in and around the New York/New Jersey Metro area. ▸ ERHC continues dedicated effort toward completion of RNAV helicopter approaches and satellite-based IFR routes along the Northeastern corridor. ▸ Top priority always has been, and remains - SAFETY Eastern Region Helicopter Council - New York Community Aviation Roundtable - LGA Committee - 25 JAN 2018 HAI FLY NEIGHBORLY PROGRAM 3 ▸ Since 1982, HAI’s Fly Neighborly Program has addressed noise abatement and public acceptance objectives with guidelines in the following areas: ▸ Pilot and operator awareness ▸ Pilot training and education ▸ Flight operations planning ▸ Public acceptance and safety ▸ Sensitivity to community concerns Eastern Region Helicopter Council - New York Community Aviation Roundtable - LGA Committee - 25 JAN 2018 HAI FLY NEIGHBORLY PROGRAM 4 ▸ “These guidelines are intended to assist pilots, operators, managers, and designated Fly Neighborly officers to establish an effective Fly Neighborly Program. The concepts and flight operations must be further tailored to suit local needs, and to ensure local or regional organizations cooperate -

April 30, 2013 Staff Report to Council

CITY OF SANTA MONICA SPECIAL CITY COUNCIL MEETING AGENDA CITY HALL COUNCIL CHAMBERS - 1685 MAIN STREET TUESDAY, APRIL 30, 2013 MEETING BEGINS AT 5:30 P.M. CALL TO ORDER PLEDGE OF ALLEGIANCE ROLL CALL (This is a special City Council meeting. Public comment is restricted to only items listed on the agenda.) 1. CLOSED SESSIONS: 1-A: Public Employee Evaluation. Title of Employees: City Manager and City Attorney The following is the order of business for items to be heard no earlier than 6:30 p.m. 3. CONSENT CALENDAR: (All items will be considered and approved in one motion unless removed by a Councilmember for discussion.) 3-A: Contract Modification for Operating the Landing Fee Program at Santa Monica Municipal Airport – recommendation to authorize the City Manager to negotiate and execute a first modification to Contract No. 9384 (CCS) with Vector-US, Inc., in the amount of $58,344 to provide for the image capture of aircraft operations, data management and reports, billing, and payment collections for the Santa Monica Airport landing fee program, resulting in a four- year amended contract with a new total amount not to exceed $458,344. 3-B: Award Construction Contract for Santa Monica Airport Runway, Taxiway and Parking Lot Improvements -- recommendation to authorize the City Manager to negotiate and execute a contract with PALP, Inc., dba Excel Paving Company, in an amount of not to exceed $672,525 for the Santa Monica Airport Runway, Taxiway and Parking Lot Improvements; authorize the issuance of an after-hours construction permit to remove rubber deposits from the runway 1 April 30, 2013 between the hours of 9 PM and 6 AM for a period of four nights, contingent on satisfying notification requirements as contained in Santa Monica Municipal Code 4.12.110; and authorize the Director of Public Works to issue any necessary change orders to complete additional work within budget authority. -

The Workforce Opportunity of Offshore Wind in New York

New York State Offshore Wind Master Plan The Workforce Opportunity of Offshore Wind in New York NYSERDA Report 17-25t December 2017 NYSERDA’s Promise to New Yorkers: NYSERDA provides resources, expertise, and objective information so New Yorkers can make confident, informed energy decisions. Mission Statement: Advance innovative energy solutions in ways that improve New York’s economy and environment. Vision Statement: Serve as a catalyst – advancing energy innovation, technology, and investment; transforming New York’s economy; and empowering people to choose clean and efficient energy as part of their everyday lives. Cover Image Source: LM Windpower New York State Offshore Wind Master Plan The Workforce Opportunity of Offshore Wind in New York Final Report Prepared for: New York State Energy Research and Development Authority Prepared by: BVG Associates Cricklade, United Kingdom Stantec New York, New York GLWN Cleveland, Ohio NYSERDA Report 17-25t December 2017 Notice This study was prepared by BVG Associates, Stantec, and GLWN (Contractors) in the course of performing work contracted for and sponsored by the State of New York through its agencies and public-benefit corporations (the State). The State and the Contractors make no warranties or representations, expressed or implied, as to the fitness for particular purpose or merchantability of any product, apparatus, or service, or the usefulness, completeness, or accuracy of any processes, methods, or other information contained, described, disclosed, or referred to in this study. The State and the Contractors make no representation that the use of any product, apparatus, process, method, or other information will not infringe privately owned rights and will assume no liability for any loss, injury, or damage resulting from, or occurring in connection with, the use of information contained, described, disclosed, or referred to in this study. -

Town of East Hampton Section V. Flooding and Erosion Policies #11-17

SECTION V FLOODING AND EROSION POLICIES #11-17 Town of East Hampton LWRP Flooding and Erosion Policies #11-17 A. INTRODUCTION 1. Flooding and Erosion Issues and their Evolution in East Hampton As an island promontory surrounded by water, East Hampton is singularly exposed to forces of the sea and weather. The Town's 110 miles of shoreline are protected by fragile beaches, dunes and bluffs, and while these are the same scenic and recreational attributes that lure tourists and second homeowners to a resort community, they are also vulnerable to winter nor'easters and catastrophic hurricanes. The awesome natural forces of storm events can quickly transform scenic views and real estate assets into disaster areas and insurance liabilities. Coastal flooding and erosion planning and policy in East Hampton have largely evolved in response to storms and other impacts of natural forces on development. Historically there has been less concern about episodic flooding and erosion in undeveloped areas where private property or public infrastructure were not at risk. This emphasis on protecting developed areas has masked the importance of maintaining unspoiled natural coastal features, both to sustain the Town's resort economy and because of their vital protective role in buffering the coast from flooding and erosion. A consideration of flooding and erosion and the coastal processes that determine them depends, as does any problem, on the point of view from which it is seen. In The Beaches are Moving, a popular classic of coastal management, authors Wallace Kaufman and Orrin Pilkey portray the conceptual dilemma thus: "The nature of sand is to move. -

F- the Pleistocene Geology of the Montauk Peninsula

155 TRIP F: THE PLEISTOCENE GEOLOGY OF THE MONTAUK PENINSULA By Walter S. Newman, David L. Thurber, David H. Krinsley, Queens College of the City University of New York; and Leslie A. Sirkin, Adelphi University. INTRODUCTION Long Island is a long narrow island reaching east-northeastward from New York City to form a "fish-like" extension of New York State. The island lies south of and is approximately parallel to the Connecticut shore of New England and is separated from it by Long Island Sound. Long Island forms the north shore of an Atlantic Ocean reentrant known as the "New York Bight". Although part of the Coastal Plain Physiographic Province, Long Island features a topography almost completely modified by glacial and proglacial processes. Two conspicuous end moraines extend from west to east along the axis of the island. The older Ronkonkoma moraine, probably Wisconsin in age, makes up a major portion of the Montauk Peninsula. The younger Harbor Hill moraine generally follows close to the north shore of Long Island east to Orient Point. The island abounds in other glacial and proglacial features such as the coalescing outwash fans and aprons which form much of the southern portion of the island. THE MONTAUK PENINSULA The Montauk Peninsula, as here defined, extends east from the village of Easthampton to Montauk Point. Montauk Point is the eastern extremity of the Ronkonkoma Moraine which forms a ridge of coalescing hills travesing the area from west to east. It marks the maximum advance of an ice sheet during late Pleistocene time. East of Montauk village, the moraine appears to be composed principally of till but does include glaciofluvial material. -

Finger Lakes Regional Airport

SENECA COUNTY FINGER LAKES REGIONAL AIRPORT DISADVANTAGED BUSINESS ENTERPRISE PROGRAM FISCAL YEARS 2017-2019 DBE PROGRAM FINGER LAKES REGIONAL AIRPORT FY 2017-2020 OBJECTIVES/POLICY STATEMENT Section 26.1, 26.23 . Seneca County has established a Disadvantaged Business Enterprise (DBE) program in accordance with regulations of the U.S. Department ofTransportation (DOT), 49 CFR Part 26. Seneca County has received Federal financial assistance from the Department of Transportation, and as a condition of receiving this assistance, Seneca County has signed an assurance that it will comply with 49 CFR Part 26. It is the policy of Seneca County to ensure that DBE's, as defined in Pait 26, have an equal opportunity to receive and participate in DOT-assisted contracts. It is also our policy: l. To ensure nondiscrimination in the award and administration of DOT assisted contracts; 2. To create a level playing field on which DBE's can compete fairly for DOT assisted contracts; 3. To ensure that the DBE Program is narrowly tailored in accordance with applicable law; 4. To ensure that only firms that fully meet 49 CFR Part 26 eligibility standards are permitted to participate as DBE's; 5. To help remove barriers to the participation of DBE's in DOT assisted contracts; and 6. To assist the development of firms that can compete successfully in the market place outside the DBE Program. Harriet Haynes, Planner has been delegated as the DBE Liaison Officer (DBELO). In that capacity, Harriet Haynes is responsible for implementing all aspects of the DBE program. Implementation of the DBE program is accorded the same priority as compliance with all other legal obligations incurred by Seneca County in its financial assistance agreements with the Department of Transportation. -

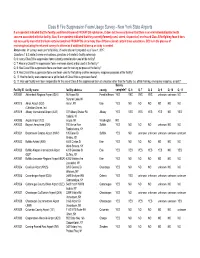

Class B Fire Suppression Foam Usage Survey

Class B Fire Suppression Foam Usage Survey - New York State Airports If a respondent indicated that the facility used/stored/disposed PFOA/PFOS substances, it does not necessarily mean that there is an environmental/public health concern associated with that facility. Also, if a respondent indicated that they currently/formerly used, stored, disposed of, or released Class B firefighting foam it does not necessarily mean that the foam contains/contained PFOA/PFOS since many Class B foams do not contain these substances. DEC is in the process of reviewing/evaluating the returned surveys to determine if additional follow-up or study is needed. Return rate: 91 surveys were sent to facilities; 90 were returned completed as of June 1, 2017. Questions 1 & 2 relate to name and address; questions 3-5 relate to facility ownership. Q. 6: Is any Class B fire suppression foam currently stored and/or used at the facility? Q. 7: Has any Class B fire suppression foam ever been stored and/or used at the facility? Q. 8: Has Class B fire suppression foam ever been used for training purposes at the facility? Q. 9: Has Class B fire suppression foam ever been used for firefighting or other emergency response purposes at the facility? Q. 10: Has the facility ever experienced a spill or leak of Class B fire suppression foam? Q. 11: Has your facility ever been responsible for the use of Class B fire suppression foam at a location other than the facility (i.e. offsite training, emergency response, or spill)? Survey Facility ID facility name facility address county complete? Q. -

Full Environmental Assessment Form Part 1 - Project and Setting

Full Environmental Assessment Form Part 1 - Project and Setting Instructions for Completing Part 1 Part 1 is to be completed by the applicant or project sponsor. Responses become part of the application for approval or funding, are subject to public review, and may be subject to further verification. Complete Part 1 based on information currently available. If additional research or investigation would be needed to fully respond to any item, please answer as thoroughly as possible based on current information; indicate whether missing information does not exist, or is not reasonably available to the sponsor; and, when possible, generally describe work or studies which would be necessary to update or fully develop that information. Applicants/sponsors must complete all items in Sections A & B. In Sections C, D & E, most items contain an initial question that must be answered either “Yes” or “No”. If the answer to the initial question is “Yes”, complete the sub-questions that follow. If the answer to the initial question is “No”, proceed to the next question. Section F allows the project sponsor to identify and attach any additional information. Section G requires the name and signature of the project sponsor to verify that the information contained in Part 1is accurate and complete. A. Project and Sponsor Information. Name of Action or Project: East Hampton Airport Noise Regulations Project Location (describe, and attach a general location map): East Hampton Town Airport, Daniel's Hole Road, Wainscott Hamlet, East Hampton Town Brief Description of Proposed Action (include purpose or need): Over the past three decades, the residents of the Town of East Hampton have experienced a significant increase in noisy aircraft traffic at the East Hampton Airport.