Towards Universal Birth Registration in Guinea

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Seasonal Malaria Chemoprevention in Guinea Maya Zhang, Stacy Attah-Poku, Noura Al-Jizawi, Jordan Imahori, Stanley Zlotkin

Seasonal Malaria Chemoprevention in Guinea Maya Zhang, Stacy Attah-Poku, Noura Al-Jizawi, Jordan Imahori, Stanley Zlotkin April 2021 This research was made possible through the Reach Alliance, a partnership between the University of Toronto’s Munk School of Global Affairs & Public Policy and the Mastercard Center for Inclusive Growth. Research was also funded by the Ralph and Roz Halbert Professorship of Innovation at the Munk School of Global Affairs & Public Policy. We express our gratitude and appreciation to those we met and interviewed. This research would not have been possible without the help of Dr. Paul Milligan from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, ACCESS-SMC, Catholic Relief Services, the Government of Guinea and other individuals and organizations in providing and publishing data and resources. We are also grateful to Dr. Kovana Marcel Loua, director general of the National Institute of Public Health in Guinea and professor at the Gamal Abdel Nasser University of Conakry, Guinea. Dr. Loua was instrumental in the development of this research — advising on key topics, facilitating ethics board approval in Guinea and providing data and resources. This research was vetted by and received approval from the Ethics Review Board at the University of Toronto. Research was conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic in compliance with local public health measures. MASTERCARD CENTER FOR INCLUSIVE GROWTH The Center for Inclusive Growth advances sustainable and equitable economic growth and financial inclusion around the world. Established as an independent subsidiary of Mastercard, we activate the company’s core assets to catalyze action on inclusive growth through research, data philanthropy, programs, and engagement. -

Coversheet for Thesis in Sussex Research Online

A University of Sussex DPhil thesis Available online via Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/ This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Please visit Sussex Research Online for more information and further details The Route of the Land’s Roots: Connecting life-worlds between Guinea-Bissau and Portugal through food-related meanings and practices Maria Abranches Doctoral Thesis PhD in Social Anthropology UNIVERSITY OF SUSSEX 2013 UNIVERSITY OF SUSSEX PhD in Social Anthropology Maria Abranches Doctoral Thesis The Route of the Land’s Roots: Connecting life-worlds between Guinea-Bissau and Portugal through food-related meanings and practices SUMMARY Focusing on migration from Guinea-Bissau to Portugal, this thesis examines the role played by food and plants that grow in Guinean land in connecting life-worlds in both places. Using a phenomenological approach to transnationalism and multi-sited ethnography, I explore different ways in which local experiences related to food production, consumption and exchange in the two countries, as well as local meanings of foods and plants, are connected at a transnational level. One of my key objectives is to deconstruct some of the binaries commonly addressed in the literature, such as global processes and local lives, modernity and tradition or competition and solidarity, and to demonstrate how they are all contextually and relationally entwined in people’s life- worlds. -

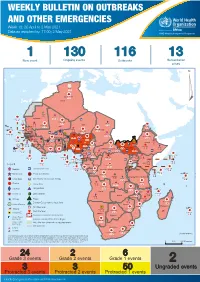

Weekly Bulletin on Outbreaks

WEEKLY BULLETIN ON OUTBREAKS AND OTHER EMERGENCIES Week 18: 26 April to 2 May 2021 Data as reported by: 17:00; 2 May 2021 REGIONAL OFFICE FOR Africa WHO Health Emergencies Programme 1 130 116 13 New event Ongoing events Outbreaks Humanitarian crises 64 0 122 522 3 270 Algeria ¤ 36 13 612 0 5 901 175 Mauritania 7 2 13 915 489 110 0 7 0 Niger 18 448 455 Mali 3 671 10 567 0 6 0 2 079 4 4 828 170 Eritrea Cape Verde 40 433 1 110 Chad Senegal 5 074 189 61 0 Gambia 27 0 3 0 24 368 224 1 069 5 Guinea-Bissau 847 17 7 0 Burkina Faso 236 49 258 384 3 726 0 165 167 2 063 Guinea 13 319 157 12 3 736 67 1 1 23 12 Benin 30 0 Nigeria 1 873 72 0 Ethiopia 540 2 556 5 6 188 15 Sierra Leone Togo 3 473 296 52 14 Ghana 70 607 1 064 6 411 88 Côte d'Ivoire 10 583 115 14 484 479 65 0 40 0 Liberia 17 0 South Sudan Central African Republic 1 029 2 49 0 97 17 25 0 22 333 268 46 150 287 92 683 779 Cameroon 7 0 28 676 137 843 20 3 1 160 422 2 763 655 2 91 0 123 12 6 1 488 6 4 057 79 13 010 7 694 112 Equatorial Guinea Uganda 1 0 542 8 Sao Tome and Principe 32 11 2 066 85 41 973 342 Kenya Legend 7 821 99 Gabon Congo 2 012 73 Rwanda Humanitarian crisis 2 310 35 25 253 337 Measles 23 075 139 Democratic Republic of the Congo 11 016 147 Burundi 4 046 6 Monkeypox Ebola virus disease Seychelles 29 965 768 235 0 420 29 United Republic of Tanzania Lassa fever Skin disease of unknown etiology 191 0 5 941 26 509 21 Cholera Yellow fever 63 1 6 257 229 26 993 602 cVDPV2 Dengue fever 91 693 1 253 Comoros Angola Malawi COVID-19 Leishmaniasis 34 096 1 148 862 0 3 840 146 Zambia 133 -

Water Diseases: Dynamics of Malaria and Gastrointestinal Diseases in the Tropical Guinea-Bissau (West Africa) Sandra Cristina De Oliveira Alves M 2018

MESTRADO SAÚDE PÚBLICA Water diseases: dynamics of malaria and gastrointestinal diseases in the tropical Guinea-Bissau (West Africa) Sandra Cristina de Oliveira Alves M 2018 Water diseases: dynamics of malaria and gastrointestinal diseases in the tropical Guinea-Bissau (West Africa) Master in Public Health || Thesis || Sandra Cristina de Oliveira Alves Supervisor: Prof. Doutor Adriano A. Bordalo e Sá Institute Biomedical Sciences University of Porto Porto, September 2018 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to show, in first place, my thankfulness to my supervisor Professor Adriano Bordalo e Sá, for “opening the door” to this project supplying the logbook raw data of Bolama Regional Hospital as well as meteorological data from the Serviço de Meterologia of Bolama, for is orientation and scientific support. The Regional Director of the Meteorological survey in Bolama, D. Efigénia, is thanked for supplying the values precipitation and temperature, retrieved from manual spread sheets. My gratitude also goes to all the team of the Laboratory Hydrobiology and Ecology, ICBAS-UP, who received me in a very friendly way, and always offers me their help (and cakes). An especial thanks to D. Lurdes Lima, D. Fernanda Ventura, Master Paula Salgado and Master Ana Machado (Ana, probable got one or two wrinkles for truly caring), thank you. Many many thanks to my friends, and coworkers, Paulo Assunção and Ana Luísa Macedo, who always gave me support and encouragement. Thank you to my biggest loves, my daughter Cecilia and to the ONE Piero. Thank you FAMILY, for the shared DNA and unconditional love. Be aware for more surprises soon. Marisa Castro, my priceless friend, the adventure never ends! This path would have been so harder and lonely without you. -

WEEKLY BULLETIN on OUTBREAKS and OTHER EMERGENCIES Week 12: 16 - 22 March 2020 Data As Reported By: 17:00; 22 March 2020

WEEKLY BULLETIN ON OUTBREAKS AND OTHER EMERGENCIES Week 12: 16 - 22 March 2020 Data as reported by: 17:00; 22 March 2020 REGIONAL OFFICE FOR Africa WHO Health Emergencies Programme 7 95 91 11 New events Ongoing events Outbreaks Humanitarian crises 201 17 Algeria 1 0 91 0 2 0 Gambia 1 0 1 0 Mauritania 14 7 20 0 9 0 Senegal 304 1 1 0Eritrea Niger 2 410 23 Mali 67 0 1 0 3 0 Burkina Faso 41 7 1 0 Cabo Verdé Guinea Chad 1 251 0 75 3 53 0 4 0 4 690 18 4 1 22 0 21 0 Nigeria 2 0 Côte d’Ivoire 1 873 895 15 4 0 South Sudan 917 172 40 0 3 970 64 Ghana16 0 139 0 186 3 1 0 14 0 Liberia 25 0 Central African Benin Cameroon 19 0 4 732 26 Ethiopia 24 0 Republic Togo 1 618 5 7 626 83 352 14 1 449 71 2 1 Uganda 36 16 Democratic Republic 637 1 169 0 9 0 15 0 Equatorial of Congo 15 5 202 0 Congo 1 0 Guinea 6 0 3 453 2 273 Kenya 1 0 253 1 Legend 3 0 6 0 38 0 37 0 Gabon 29 981 384 Rwanda 21 0 Measles Humanitarian crisis 2 0 4 0 4 998 63 Burundi 7 0 Hepatitis E 8 0 Monkeypox 8 892 300 3 294 Seychelles 30 2 108 0 Tanzania Yellow fever 12 0 Lassa fever 79 0 Dengue fever Cholera Angola 547 14 Ebola virus disease Rift Valley Fever Comoros 129 0 2 0 Chikungunya Malawi 218 0 cVDPV2 2 0 Zambia Leishmaniasis Mozambique 3 0 3 0 COVID-19 Plague Zimbabwe 313 13 Madagascar Anthrax Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever Namibia 286 1 Malaria 2 0 24 2 12 0 Floods Meningitis 3 0 Mauritius Cases 7 063 59 1 0 Deaths Countries reported in the document Non WHO African Region Eswatini N WHO Member States with no reported events W E 3 0 Lesotho4 0 402 0 South Africa 20 0 S South Africa Graded events † 40 15 1 Grade 3 events Grade 2 events Grade 1 events 39 22 20 31 Ungraded events ProtractedProtracted 3 3 events events Protracted 2 events ProtractedProtracted 1 1 events event Health Emergency Information and Risk Assessment Overview This Weekly Bulletin focuses on public health emergencies occurring in the WHO Contents African Region. -

How Can the Health Systems of Guinea, Sierra Leone and Liberia Be Improved?

How can the health systems of Guinea, Sierra Leone and Liberia be improved? Results of three Open Space Conferences with participants from government and civil society, healthcare providers and users, community health volunteers and traditional practitioners, donors and aid organization Table of Content Executive summary 4 1. – Introduction 5 2. – Methodology of the Open Space Conference 6 3. – Similarities in discussion of topics and solutions 7 4. – Differences in the discussions 9 5. – Operational research and support needs 10 6. – Conclusion 11 Annex A: Guinea – Detailed results 12 A 1. – The Conference in Guinea 13 A 2. – topics raised and discussed 14 a. Improvement of health care facilities and management 14 b. Health workers and human resource management 14 c. Referral systems 15 d. Infection Prevention & Control and early warning systems 16 e. Reasons and aftermath of the Ebola crisis 17 F. Nutrition and food security 17 A 3. – Aspects relating to vulnerable groups 18 a. Women 18 b. Infants and children under 5 years 19 c. Persons living with disabilities or chronic illnesses 19 A 4. – Community involvement 19 A 5. – Top 7 Community Action Priorities 20 Annex B: Liberia – Detailed results 22 B 1. – The Conference in Liberia 23 B 2. – topics raised and discussed 24 a. Better health through water, sanitation and environment 24 b. Improvement of health care facilities and management 24 c. Referral systems for better health care 24 d. Infection Prevention & Control and early warning systems 25 e. Health workers and human resource management 25 f. Traditional medicine 27 g. Reasons and aftermath of the Ebola crisis 27 B 3. -

Environmental'profile Of, GUINEA Prepared by the Arid Lands Information Center Office of Arid Lands Studies University Of

DRAFT i Environmental'Profile of, GUINEA Prepared by the Arid Lands Information Center Office of Arid Lands Studies University of Arizona Tucson, Arizona 85721 Department of State Purchase Order No. 1021-210575, for U.S. Man and the Biosphere Secretariat' Department of State Washington, D.C. December 1983 - Robert G.:Varady, Compiler -, THE.UNrrED STATES NATIO C III F MAN AN ITHE BIOSPH.RE Department of State, ZO/UCS WASHINGTON. C C. 20520 An Introductory Note on Draft Environmental Profiles: The attached draft environmental report has been prepared under a contract between the U.S. Agency for International Development (AID), Office of Forestry, Environment, and Natural Resources (ST/FNR) and the U.S. Man and the Biosphere (MAB) Program. It is a preliminary review of information available in the United States on the status of the environment and the natural resources of the identified country and is one of a series of similar studies on countries which receive U.S. bilateral assistance. This report is the first step in a process to develop better information for the AID Mission, for host country officials, and others on the environmental situation in specific countries and begins to identify the most critical areas of concern. A more comprehensive study may be undertaken in each country by Regional Bureaus and/or AID Missions. These would involve local scientists in a more detailed examination of the actual situations as well as a better definition of issues, problems and priorities. Such "Phase II" studies would provide substance for the Agency's Country Development Strategy Statements as well as justifications for program initiatives in the areas of environment and natural resources. -

Mapping Maternal and Newborn Healthcare Access in West African Countries

Mapping maternal and newborn healthcare access in West African Countries Dorothy Ononokpono University of Uyo Bernard Baffour ( [email protected] ) Australian National University https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9820-2617 Alice Richardson Australian National University Research article Keywords: Maternal and newborn health, districts, West Africa, mapping, geospatial analysis, buffer analysis. Posted Date: August 13th, 2019 DOI: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.2.11583/v2 License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Read Full License Page 1/28 Abstract Background: The Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) three emphasizes the need to improve maternal and newborn health, and reduce global maternal mortality ratio to less than 70 per 100 000 live births by 2030. Achieving the SDG goal 3.1 target will require evidence based data on concealed inequities in the distribution of maternal and child health outcomes and their linkage to healthcare access. The objectives of this study were to estimate the number of women of reproductive age, pregnancies and live births at subnational level using high resolution maps and to quantify the number of pregnancies within user- dened distances or travel times of a health facility in three poor resource West African countries: Mali, Guinea and Liberia. Methods: The maternal and newborn health outcomes were estimated and mapped for the purpose of visualization using geospatial analytic tools. Buffer analysis was then performed to assess the proximity of pregnancies to health facilities with the aim of identifying pregnancies with inadequate access (beyond 50km) to a health facility. Results: Results showed wide variations in the distribution of maternal and newborn health outcomes across the countries of interest and districts of each of the countries. -

Thesis Was Financially Supported by the Stichting Sarphati and the Medical Researchh Council

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) HIV-2 in West Africa. Epidemiological studies Schim van der Loeff, M.F. Publication date 2003 Document Version Final published version Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Schim van der Loeff, M. F. (2003). HIV-2 in West Africa. Epidemiological studies. General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:07 Oct 2021 JÉfoo JïP^h V V HIV-2lm m EPIDEMIOLOGICAL L MAARTENN F. SCHIM VAN DER LOEFF HIV-22 IN WEST AFRICA EPIDEMIOLOGICALL STUDIES Printingg of this thesis was financially supported by the Stichting Sarphati and the Medical Researchh Council. ISBNN 90-6464-834-4 Printedd by Ponsen & Looi jen - Wageningen Coverr design: Casper Schim van der Loeff - Utrecht ©© 2003 by M. -

Women's Resilience: Integrating Gender in the Response to Ebola

OFFICE OF THE SPECIAL ENVOY ON GENDER Women’s Resilience: Integrating Gender in the Response to Ebola Women’s Resilience: Integrating Gender in the Response to Ebola Emeka Kupeski, 2015 Kupeski, Emeka Rights and permissions All rights reserved. The information in this publication may be reproduced provided the source is acknowledged. Reproduction of the publication or any part thereof for commercial purposes is forbidden. The views expressed in this paper are entirely those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the view of the African Development Bank, its Board of Directors, or the countries they represent. Copyright © African Development Bank 2016 African Development Bank Immeuble du Centre de commerce International d’Abidjan CCIA Avenue Jean-Paul II 01 BP 1387 Abidjan 01, Côte d’Ivoire Tel.: (+225) 20 26 10 20 Email: [email protected] Website: www.afdb.org Foreword In August 2014, the Office of the Special Envoy on Gender received a call from the First Lady of Sierra Leone urging the Bank to integrate the socio-economic recovery of Liberian, Sierra Leonean and Guinean women into our response to the Ebola epidemic. Source: AfDB Source: The fact that the African Development Bank’s investments in public health systems in these countries were thoroughly gender mainstreamed did not quite bring about the recovery of women on the ground with the immediacy required. Thus, as the premier African development finance institution, it was important for us to think altogether differently so as not to lose the post conflict gains made by men and women in the region. -

Thematic Review: Understanding the Health Financing Landscape And

Thematic Review Understanding the Health Financing Landscape and Documenting of the Types of User Fees (Formal and Informal) Affecting Access to HIV, TB, and Malaria Services in West and Central Africa April 30, 2020 Submitted to: The Global Fund Submitted by: ICF Understanding the Health Financing Landscape and Documenting of the Types of User Fees (Formal and Informal) Affecting Access to HIV, TB, and Malaria Services in West and Central Africa Table of Contents Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................................. iii Acronyms ............................................................................................................................................. iv Executive Summary ............................................................................................................................. 1 Introduction .......................................................................................................................................... 7 Background .............................................................................................................................................................................. 7 Justification for the Study ..................................................................................................................................................... 7 Intended Use of the Study .................................................................................................................................................. -

Data Sharing During the West Africa Ebola Public Health Emergency: Case Study Report November 2018

Data Sharing during the West Africa Ebola Public Health Emergency: Case Study Report November 2018 1. Introduction a. Background to the 2013-15 outbreak: On December 6, 2013, Emile Ouamouno, a 2-year-old from Meliandou, a small village in the Guinea forestière, died after four days of suffering from vomiting, fever, and black stool.1 The cause of his infection is unknown, although he is now widely considered to be the index case for the outbreak of Ebola hemorrhagic fever now Ebola Virus Disease (EVD). Within a month, the child’s sister, mother, and grandmother died after experiencing similar symptoms.3 The funeral for the latter was attended by a midwife who passed the disease to relatives in another village, and to a health care worker treating her.4 That health care worker was treated at a hospital in Macenta, about 80 kilometers (50 miles) east. A doctor who treated her contracted Ebola. The doctor then passed it to his brothers in Kissidougou, 133 kilometers (83 miles) away. 4 Although the outbreak of EVD originated in Guinea, between December 2013 and March 2014, it spread more rapidly in the eastern regions of Sierra Leone and then in North Central Liberia, followed by Nzérékoré in Guinea. 5 Between December 2013 and April 10, 2016, a total of 28,616 suspected, probable, and confirmed cases of Ebola virus disease (EVD) were reported. 5 A total of 11,310 deaths were attributed to the outbreak. 5 The largest numbers of cases and deaths occurred in Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone, but 36 cases were reported from Italy, Mali, Nigeria, Senegal, Spain, the United Kingdom, and the United States.6 After reaching a peak of 950 confirmed cases per week in September 2014, the incidence dropped precipitously toward the end of that year.