Coversheet for Thesis in Sussex Research Online

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Seasonal Malaria Chemoprevention in Guinea Maya Zhang, Stacy Attah-Poku, Noura Al-Jizawi, Jordan Imahori, Stanley Zlotkin

Seasonal Malaria Chemoprevention in Guinea Maya Zhang, Stacy Attah-Poku, Noura Al-Jizawi, Jordan Imahori, Stanley Zlotkin April 2021 This research was made possible through the Reach Alliance, a partnership between the University of Toronto’s Munk School of Global Affairs & Public Policy and the Mastercard Center for Inclusive Growth. Research was also funded by the Ralph and Roz Halbert Professorship of Innovation at the Munk School of Global Affairs & Public Policy. We express our gratitude and appreciation to those we met and interviewed. This research would not have been possible without the help of Dr. Paul Milligan from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, ACCESS-SMC, Catholic Relief Services, the Government of Guinea and other individuals and organizations in providing and publishing data and resources. We are also grateful to Dr. Kovana Marcel Loua, director general of the National Institute of Public Health in Guinea and professor at the Gamal Abdel Nasser University of Conakry, Guinea. Dr. Loua was instrumental in the development of this research — advising on key topics, facilitating ethics board approval in Guinea and providing data and resources. This research was vetted by and received approval from the Ethics Review Board at the University of Toronto. Research was conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic in compliance with local public health measures. MASTERCARD CENTER FOR INCLUSIVE GROWTH The Center for Inclusive Growth advances sustainable and equitable economic growth and financial inclusion around the world. Established as an independent subsidiary of Mastercard, we activate the company’s core assets to catalyze action on inclusive growth through research, data philanthropy, programs, and engagement. -

Prospects for Commercial Agriculture in the Guinea Savannah Zone and Beyond Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized

49046 Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Agriculture andRuralAgriculture Development DIRECTIONS INDEVELOPMENT the GuineaSavannah Zone andBeyond Prospects forCommercialProspects Agriculture in Awakening Africa’s Awakening Sleeping Giant Awakening Africa’s Sleeping Giant Awakening Africa’s Sleeping Giant Prospects for Commercial Agriculture in the Guinea Savannah Zone and Beyond © 2009 The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank 1818 H Street, NW Washington, DC 20433 Telephone 202-473-1000 Internet www.worldbank.org E-mail [email protected] All rights reserved. 1 2 3 4 :: 12 11 10 09 This volume is a product of the staff of the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this volume do not necessarily reflect the views of the Executive Directors of The World Bank or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The bound- aries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of The World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. Rights and Permissions The material in this publication is copyrighted. Copying and/or transmitting portions or all of this work without permission may be a violation of applicable law. The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank encourages dissemination of its work and will normally grant permission to reproduce portions of the work promptly. For permission to photocopy or reprint any part of this work, please send a request with complete information to the Copyright Clearance Center Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, USA; telephone: 978-750-8400; fax: 978-750-4470; Internet: www.copyright.com. -

OCCASION This Publication Has Been Made Available to the Public on The

OCCASION This publication has been made available to the public on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the United Nations Industrial Development Organisation. DISCLAIMER This document has been produced without formal United Nations editing. The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this document do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO) concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries, or its economic system or degree of development. Designations such as “developed”, “industrialized” and “developing” are intended for statistical convenience and do not necessarily express a judgment about the stage reached by a particular country or area in the development process. Mention of firm names or commercial products does not constitute an endorsement by UNIDO. FAIR USE POLICY Any part of this publication may be quoted and referenced for educational and research purposes without additional permission from UNIDO. However, those who make use of quoting and referencing this publication are requested to follow the Fair Use Policy of giving due credit to UNIDO. CONTACT Please contact [email protected] for further information concerning UNIDO publications. For more information about UNIDO, please visit us at www.unido.org UNITED NATIONS INDUSTRIAL DEVELOPMENT ORGANIZATION Vienna International Centre, P.O. Box -

Guinea Bissau Ebola Situation Report

Picture goes here Resize before including pictures or maps in the Guinea Bissau SitRep *All Ebola statistics in this report are drawn The SitRep should not exceed 3mb total from the Ministry of Health and Social Welfare (MoHSW) Ebola SitRep #165, which Ebolareports cumulative cases as of 27 October 2014 (from 23 May toSituation 27 October 2014). Report 12 August 2015 HIGHLIGHTS SITUATION IN NUMBERS Owing to a fragile health system in Guinea-Bissau establishing a sanitary As of 12 August 2015 corridor along the border regions, the islands and the capital Bissau, continues to be a major challenge 500,000 As a trusted partner in Guinea Bissau, UNICEF continues to perform and Children living in high risk areas deliver its programme, maintaining relations with all sectors of the government, and providing technical assistance in ensuring systems are in place in case of a potential Ebola crisis UNICEF funding needs until August 2015 UNICEF provides strong support to the government and people in USD 5,160,712 million Guinea-Bissau in Ebola prevention on several fronts. Actions this week focused on trainings in Education, Protection and C4D (Youth). UNICEF funding gap USD 1,474,505 million Community engagement initiatives continued to be implemented with UNICEF support, focusing but not limited to high risk communities of Gabu and Tombali, bordering Guinea Conakry. The activities are implemented through a network of local NGOs, community based organisations, Christian and Islamic church-based organizations, the Traditional Leaders Authority, the Association of Traditional Healers PROMETRA, the taxi drivers unions SIMAPPA and community radios. Several meetings were held with government and civil society counterparts both in Bissau and in Gabu province, with an emphasis on securing a commitment for more thorough coordination among partners, particularly given the entry of new players in the country, and to avoid potential duplication of efforts. -

Configurações, 17 | 2016 2

Configurações Revista de sociologia 17 | 2016 Sociedade, Autoridade e Pós-memórias Edição electrónica URL: http://journals.openedition.org/configuracoes/2883 DOI: 10.4000/configuracoes.2883 ISSN: 2182-7419 Editora Centro de Investigação em Ciências Sociais Edição impressa Data de publição: 27 junho 2016 ISSN: 1646-5075 Refêrencia eletrónica Configurações, 17 | 2016, « Sociedade, Autoridade e Pós-memórias » [Online], posto online no dia 30 junho 2016, consultado o 23 setembro 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/configuracoes/ 2883 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/configuracoes.2883 Este documento foi criado de forma automática no dia 23 setembro 2020. © CICS 1 SUMÁRIO Ficha Técnica Direção da Revista Configurações Introdução - Sociedade, autoridade e pós-memórias Manuel Carlos Silva, Sheila Khan e Francisco Azevedo Mendes Virtual experience, collective memory, and the configurationmof the public sphere through the mass media. The example of Ex-Yugoslavia Jeffrey Andrew Barash Memórias amnésicas? Nação, discurso político e representações do passado colonial* Miguel Cardina As cores da investigação em Portugal: África, identidade e memória* Sheila Khan Currículo, memória e fragilidades: contributos para (re)pensar a educação na Guiné-Bissau José Carlos Morgado, Júlio Santos e Rui da Silva Writing and translating Timorese oral tradition* Vicente Paulino As memórias “arrumam-se em quadros fixos”: a experiência traumática de Solange Matos, narradora de A Noite das Mulheres Cantoras Patrícia I. Martinho Ferreira “Now we don’t have anything”: -

The Herpetofauna of the Bijagós Archipelago, Guinea-Bissau (West Africa) and a First Country-Wide Checklist

Bonn zoological Bulletin 61 (2): 255–281 December 2012 The herpetofauna of the Bijagós archipelago, Guinea-Bissau (West Africa) and a first country-wide checklist 1 2,3 3 Mark Auliya , Philipp Wagner & Wolfgang Böhme 1 Helmholtz Centre for Environmental Research – UFZ, Department of Conservation Biology, Permoserstr. 15, D-04318 Leipzig, Germany. 2 Department of Biology, Villanova University, 800 Lancaster Avenue, Villanova, Pennsylvania 19085, USA. 3 Zoologisches Forschungsmuseum Alexander Koenig, Adenauerallee 160, D-53113 Bonn. Abstract. An annotated checklist of amphibians and reptiles from the Bijagós archipelago (Guinea-Bissau) with com- ments on the species’ distribution, systematics and natural history traits is presented here for the first time. During two field surveys 13 anurans and 17 reptile species were recorded from the archipelago of which several species represent either first records for the islands, i.e., Silurana tropicalis, Hemisus g. guineensis, Leptopelis viridis, Hemidactylus an- gulatus, Chamaeleo gracilis, Trachylepis perrotetii, Philothamnus heterodermus, Toxicodryas blandingii, Naja melanoleuca and Thelotornis kirtlandii or first country records, i.e., Amietophrynus maculatus, Ptychadena pumilio, P. bibroni, Phrynobatrachus calcaratus, P. francisci, Leptopelis bufonides, Hyperolius occidentalis, H. nitidulus, H. spatzi, Kassina senegalensis and Thrasops occidentalis. Species diversity reflects savanna and forest elements and a complete herpetofaunal checklist of the country is provided. Key words. West Africa, Guinea-Bissau, Bijagós archipelago, herpetofauna, first country records. INTRODUCTION The former Portugese colony Guinea-Bissau is an au- Guinea-Bissau's tropical climate is characterised by a tonomous country since 1974 and is bordered by Senegal dry season (November to May), and a wet season from in the north, Guinea in the east and south, and by the At- June to October with average annual rainfall between lantic Ocean in the west (Fig. -

West African Chimpanzees

Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan West African Chimpanzees Compiled and edited by Rebecca Kormos, Christophe Boesch, Mohamed I. Bakarr and Thomas M. Butynski IUCN/SSC Primate Specialist Group IUCN The World Conservation Union Donors to the SSC Conservation Communications Programme and West African Chimpanzees Action Plan The IUCN Species Survival Commission is committed to communicating important species conservation information to natural resource managers, decision makers and others whose actions affect the conservation of biodiversity. The SSC’s Action Plans, Occasional Papers, newsletter Species and other publications are supported by a wide variety of generous donors including: The Sultanate of Oman established the Peter Scott IUCN/SSC Action Plan Fund in 1990. The Fund supports Action Plan development and implementation. To date, more than 80 grants have been made from the Fund to SSC Specialist Groups. The SSC is grateful to the Sultanate of Oman for its confidence in and support for species conservation worldwide. The Council of Agriculture (COA), Taiwan has awarded major grants to the SSC’s Wildlife Trade Programme and Conser- vation Communications Programme. This support has enabled SSC to continue its valuable technical advisory service to the Parties to CITES as well as to the larger global conservation community. Among other responsibilities, the COA is in charge of matters concerning the designation and management of nature reserves, conservation of wildlife and their habitats, conser- vation of natural landscapes, coordination of law enforcement efforts, as well as promotion of conservation education, research, and international cooperation. The World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) provides significant annual operating support to the SSC. -

Systematic Country Diagnostic (Scd)

Document of The World Bank FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY Public Disclosure Authorized Report No. 106725-GB GUINEA-BISSAU TURNING CHALLENGES INTO OPPORTUNITIES FOR POVERTY REDUCTION AND INCLUSIVE GROWTH Public Disclosure Authorized SYSTEMATIC COUNTRY DIAGNOSTIC (SCD) JUNE, 2016 Public Disclosure Authorized International Development Association Country Department AFCF1 Africa Region Public Disclosure Authorized International Finance Corporation Sub-Saharan Africa Department Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We would like to thank the following colleagues who have contributed through invaluable inputs, comments or both: Vera Songwe, Marie-Chantal Uwanyiligira, Philip English, Greg Toulmin, Francisco Campos, Zenaida Hernandez, Raja Bentaouet, Paolo Zacchia, Eric Lancelot, Johannes G. Hoogeveen, Ambar Narayan, Neeta G. Sirur, Sudharshan Canagarajah, Edson Correia Araujo, Melissa Merchant, Philippe Auffret, Axel Gastambide, Audrey Ifeyinwa Achonu, Eric Mabushi, Jerome Cretegny, Faheen Allibhoy, Tanya Yudelman, Giovanni Ruta, Isabelle Huynh, Upulee Iresha Dasanayake, Anta Loum Lo, Arthur Foch, Vincent Floreani, Audrey Ifeyinwa Achonu, Daniel Kirkwood, Eric Brintet, Kjetil Hansen, Alexandre Marc, Asbjorn Haland, Simona Ross, Marina Temudo, Pervaiz Rashid, Rasmane Ouedraogo, Charl Jooste, Daniel Valderrama, Samuel Freije and John Elder. We are especially thankful to Marcelo Leite Paiva who provided superb research assistance for the elaboration of this report. We also thank the peer reviewers: Trang Van Nguyen, Sebastien Dessus -

World Bank Document

The World Bank Guinea Integrated Agricultural Development Project (GIADP/PDAIG) (P164326) Note to Task Teams: The following sections are system generated and can only be edited online in the Portal. Please delete this note when finalizing the document. Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Combined Project Information Documents / Integrated Safeguards Datasheet (PID/ISDS) Public Disclosure Authorized Appraisal Stage | Date Prepared/Updated: 05-May-2018 | Report No: PIDISDSA23847 Public Disclosure Authorized Apr 01, 2018 Page 1 of 26 The World Bank Guinea Integrated Agricultural Development Project (GIADP/PDAIG) (P164326) BASIC INFORMATION OPS_TABLE_BASIC_DATA A. Basic Project Data Country Project ID Project Name Parent Project ID (if any) Guinea P164326 Guinea Integrated Agricultural Development Project (GIADP/PDAIG) Region Estimated Appraisal Date Estimated Board Date Practice Area (Lead) AFRICA 30-Apr-2018 18-Jun-2018 Agriculture Financing Instrument Borrower(s) Implementing Agency Investment Project Financing Ministry of Economy and Ministry of Agriculture Finance Proposed Development Objective(s) The project development objective is to increase agricultural productivity and market access for producers and agribusiness Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) in selected value chains in the project areas. Components Component 1: Increasing agricultural productivity Component 2: Increasing Market Access Component 3: Strenghening institutional capacity Component 4: Project coordination and implementation PROJECT FINANCING -

Guinea Bissau: the Law and Fgm

GUINEA BISSAU: THE LAW AND FGM August 2018 In Guinea Bissau, the prevalence of FGM in women aged 15–49 is 52.1%. The regions with the highest prevalence are in the east: Gabú (95.8%) and Bafatá (86.9%). Oio Gabú 95.8% Cacheu 55.2% Bafatá 11.8% 86.9% B Biombo 7.8% S SAB 31.8% Q Quinara 58.5% Bolama Tombali 9.3% 51.3% 91% - 100% 76% - 90% 51% - 75% 26% - 50% Prevalence of FGM in Guinea Bissau by region 11% - 25% < 10% [Data source MICS 2018-19] © 28 Too Many § FGM is usually practised on girls aged 4 to 14, but also on babies and women nearing marriage or close to giving birth. § More than three quarters of women have experienced ‘Flesh removed’, the type of FGM practised most commonly. § Almost all FGM is carried out by traditional practitioners. § 75.8% of women aged 15–49 who have heard of FGM believe it should be stopped. Source of data: Ministério da Economia e Finanças, Direcção Geral do Plano/Instituto Nacional de Estatística (INE) (2018-19) Inquérito aos Indicadores Múltiplos (MICS6) 2018-19, Relatório Final. Available at https://mics-surveys- prod.s3.amazonaws.com/MICS6/West%20and%20Central%20Africa/Guinea-Bissau/2018- 2019/Survey%20findings/Guinea%20Bissau%202018- 19%20MICS%20Survey%20Findings%20Report_Portuguese.pdf For further information on FGM in Guinea Bissau see https://www.28toomany.org/guinea-bissau/. 1 Domestic Legal Framework Overview of Domestic Legal Framework in Guinea Bissau The Constitution explicitly prohibits: X Violence against women and girls X Harmful practices X Female genital mutilation (FGM) National legislation: ü Provides a clear definition of FGM ü Criminalises the performance of FGM ü Criminalises the procurement, arrangement and/or assistance of acts of FGM ü Criminalises the failure to report incidents of FGM X* Criminalises the participation of medical professionals in acts of FGM ü Criminalises the practice of cross-border FGM ü Government has a strategy in place to end FGM * Not directly criminalised – main FGM law applies universally (see below). -

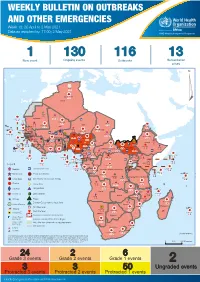

Weekly Bulletin on Outbreaks

WEEKLY BULLETIN ON OUTBREAKS AND OTHER EMERGENCIES Week 18: 26 April to 2 May 2021 Data as reported by: 17:00; 2 May 2021 REGIONAL OFFICE FOR Africa WHO Health Emergencies Programme 1 130 116 13 New event Ongoing events Outbreaks Humanitarian crises 64 0 122 522 3 270 Algeria ¤ 36 13 612 0 5 901 175 Mauritania 7 2 13 915 489 110 0 7 0 Niger 18 448 455 Mali 3 671 10 567 0 6 0 2 079 4 4 828 170 Eritrea Cape Verde 40 433 1 110 Chad Senegal 5 074 189 61 0 Gambia 27 0 3 0 24 368 224 1 069 5 Guinea-Bissau 847 17 7 0 Burkina Faso 236 49 258 384 3 726 0 165 167 2 063 Guinea 13 319 157 12 3 736 67 1 1 23 12 Benin 30 0 Nigeria 1 873 72 0 Ethiopia 540 2 556 5 6 188 15 Sierra Leone Togo 3 473 296 52 14 Ghana 70 607 1 064 6 411 88 Côte d'Ivoire 10 583 115 14 484 479 65 0 40 0 Liberia 17 0 South Sudan Central African Republic 1 029 2 49 0 97 17 25 0 22 333 268 46 150 287 92 683 779 Cameroon 7 0 28 676 137 843 20 3 1 160 422 2 763 655 2 91 0 123 12 6 1 488 6 4 057 79 13 010 7 694 112 Equatorial Guinea Uganda 1 0 542 8 Sao Tome and Principe 32 11 2 066 85 41 973 342 Kenya Legend 7 821 99 Gabon Congo 2 012 73 Rwanda Humanitarian crisis 2 310 35 25 253 337 Measles 23 075 139 Democratic Republic of the Congo 11 016 147 Burundi 4 046 6 Monkeypox Ebola virus disease Seychelles 29 965 768 235 0 420 29 United Republic of Tanzania Lassa fever Skin disease of unknown etiology 191 0 5 941 26 509 21 Cholera Yellow fever 63 1 6 257 229 26 993 602 cVDPV2 Dengue fever 91 693 1 253 Comoros Angola Malawi COVID-19 Leishmaniasis 34 096 1 148 862 0 3 840 146 Zambia 133 -

World Bank Document

Document of The World Bank Public Disclosure Authorized FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY Report No: 49557-GW PROJECT APPRAISAL DOCUMENT ON A Public Disclosure Authorized PROPOSED GRANT IN THE AMOUNT OF SDR3.3 MILLION (US$5.0 MILLION EQUIVALENT) TO THE REPUBLIC OF GUINEA-BISSAU FOR A RURAL COMMUNITY-DRIVEN DEVELOPMENT PROJECT (RCDD) Public Disclosure Authorized August 28,2009 Human Development Sector Africa Technical Families, Social Protection (AFTSP) Country Department 1 AFCF 1 Africa Region Public Disclosure Authorized This document has a restricted distribution and may be used by recipients only in the performance of their official duties. Its contents may not otherwise be disclosed without World Bank authorization. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (Exchange Rate Effective July 3 1,2009) CurrencyUnit = XOF US$1 = 475 XOF 1 XOF = US$0.0021 FISCAL YEAR January 1 - December 31 ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS AfDB African Development Bank ASC Administrative Sector Council (Conselho Directivo Sectorial) CAIA Ce'ZuZa de AvaZiaqGo dos Impactos Ambientais (Cell for Environmental Impact Evaluation) CBMP Coastal and Biodiversity Management Project CBO Community-based Organization CDD Community-Driven Development CEM Country Economic Memorandum CG Comite' de GestGo (Community Management Committee) CIFA Country Integrated Fiduciary Assessment CPAR Country Procurement Assessment Report CQS Consultant' s Qualification Selection cso Civil Society Organization DA Designated Account DGCP DirecqGo Geral dos Concursos Pdblicos (Directorate for Public Procurement) EC European Commision