Diversity Within Canada's Indigenous

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1.1 Passamaquoddy, They Speak Malecite-Passamaquoddy (Also Known As Maliseet- Passamaquoddy

1.1 Passamaquoddy, they speak Malecite-Passamaquoddy (also known as Maliseet- Passamaquoddy. It is an endangered language from the Algonquian language family (1) 1.2 Pqm (2) 1.3 45.3,-66.656 (3) 1.4 The Passamaquoddy tribe belonged to the loose confederation of eastern American Indians known as the Wabanaki Alliance, together with the Maliseet, Mi'kmaq, Abenaki, and Penobscot tribes. Today most Passamaquoddy people live in Maine, in two communities along the Passamaquoddy Bay that bears their name. However, there is also a band of a few hundred Passamaquoddy people in New Brunswick. The French referred to both the Passamaquoddy and their Maliseet kinfolk by the same name, "Etchimins." They were closely related peoples who shared a common language, but the two tribes have always considered themselves politically independent. Smallpox and other European diseases took a heavy toll on the Passamaquoddy tribe, which was reduced from at least 20,000 people to no more than 4000. Pressured by European and Iroquois aggression, the Maliseet and Passamaquoddy banded together with their neighbors the Abenakis, Penobscots, and Micmacs into the short-lived but formidable Wabanaki Confederacy. This confederacy was no more than a loose alliance, however, and neither the Maliseet nor the Passamaquoddy nation ever gave up their sovereignty. Today the Passamaquoddy live primarily in the United States and the Maliseet in Canada, but the distinction between the two is not imposed by those governments--the two tribes have always been politically distinct entities. (4) 1.5 After working with the French and joining the Abnaki confederation against the English, many converted to Catholicism. -

Scaling Memory: Reparation Displacement and the Case of BC

Scaling Memory: Reparation Displacement and the Case of BC MATT JAMES University of Victoria In British Columbia, people tend to view history as something that happened last weekend.... Happily, it doesn’t matter here who your ancestors were or who did what to whom 300 years ago. Lisa Hobbs Birnie ~1996! Racist injustices have played a central role in shaping British Columbia; it could hardly be otherwise in a white-dominated settler society built on an ongoing history of Indigenous dispossession and 75 initial years of official racism against Asians. Yet despite the spread of an “age of apol- ogy” ~Gibney et al., 2008!, characterized in many locales by a growing introspection over patterns of historic injustice, considerations of repara- tion still seem marginal in BC, an anomaly to which this article responds. Charting the contours of an amnesiac culture of memory, the follow- ing pages argue that BC’s aloofness from the age of apology reflects a phenomenon I call “reparation displacement.” While some recalcitrant communities resist calls to repair injustice by denying responsibility or claiming no injustice has occurred, reparation displacement works more subtly, redirecting understandings of responsibility instead. In the BC case, reparation displacement is intertwined with the politics of federalism; issues of racist injustice in BC have been conceived almost exclusively— not only by officials but often by redress activists themselves—as mat- ters of federal rather than provincial shame. While more informed debates about Canadian belonging have followed federal apologies for wrongs inflicted on various groups, including Japanese Canadians, Chinese Cana- dians and Indigenous peoples ~James, 2006: 243–45!, BC is a different Acknowledgments: The author would like to thank Caroline Andrew, Alan Cairns, Avigail Eisenberg, Steve Dupré, Chris Kukucha, Daniel Woods, and the two CJPS reviewers for helpful comments on earlier drafts. -

Indigenous People of Western New York

FACT SHEET / FEBRUARY 2018 Indigenous People of Western New York Kristin Szczepaniec Territorial Acknowledgement In keeping with regional protocol, I would like to start by acknowledging the traditional territory of the Haudenosaunee and by honoring the sovereignty of the Six Nations–the Mohawk, Cayuga, Onondaga, Oneida, Seneca and Tuscarora–and their land where we are situated and where the majority of this work took place. In this acknowledgement, we hope to demonstrate respect for the treaties that were made on these territories and remorse for the harms and mistakes of the far and recent past; and we pledge to work toward partnership with a spirit of reconciliation and collaboration. Introduction This fact sheet summarizes some of the available history of Indigenous people of North America date their history on the land as “since Indigenous people in what is time immemorial”; some archeologists say that a 12,000 year-old history on now known as Western New this continent is a close estimate.1 Today, the U.S. federal government York and provides information recognizes over 567 American Indian and Alaskan Native tribes and villages on the contemporary state of with 6.7 million people who identify as American Indian or Alaskan, alone Haudenosaunee communities. or combined.2 Intended to shed light on an often overlooked history, it The land that is now known as New York State has a rich history of First includes demographic, Nations people, many of whom continue to influence and play key roles in economic, and health data on shaping the region. This fact sheet offers information about Native people in Indigenous people in Western Western New York from the far and recent past through 2018. -

Aboriginal Title and Free Entry Mining Regimes in Northern Canada

Aboriginal Title and Free Entry Mining Regimes in Northern Canada Prepared for the Canadian Arctic Resources Committee by Nigel Bankes Professor, Faculty of Law The University of Calgary [email protected] and Cheryl Sharvit LLM Candidate Faculty of Law The University of Calgary [email protected] July 1998 ISBN 0-919996-77-9 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgments 1.0 Introduction .................................................................................................................................1 1.1 Two Hypotheses..........................................................................................................................1 1.1.1 The Free Entry Hypothesis.........................................................................................1 1.1.2 The 1870 Order Hypothesis.......................................................................................2 1.1.3 Other Possible Hypotheses.........................................................................................3 1.1.4 Mining legislation and land claim agreements ...............................................................6 1.2 Background.................................................................................................................................6 1.2.1 Some Examples of Conflicts Between Free Entry Mineral Exploration and Aboriginal Peoples...............................................................................................7 1.2.1.1 Baker Lake Uranium Exploration........................................................7 -

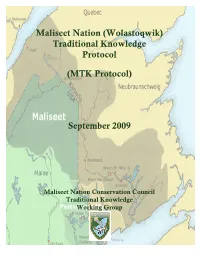

Traditional Knowledge Protocol

Maliseet Nation (Wolastoqwik) Traditional Knowledge Protocol (MTK Protocol) September 2009 Maliseet Nation Conservation Council Traditional Knowledge Working Group Table of Contents Foreword …………………………………………………………………………… i 1.0 Introduction ………………………………………………………………… 1 2.0 Definitions …………………………………………………………………… 2 3.0 Interpretation ………………………………………………………………… 3 4.0 MTK Methodology …………………………………………………………… 4 I Project Planning ………………………………………………………… 5 II Delivery and Implementation ……………………………………………… 6 III Finalizing Report and Disclosure ………………………………………… 7 5.0 Amendments …………………………………………………………………… 7 Appendices …………………………………………………………………………… 8 Maliseet Leadership Proclamation / Resolution …………………………… 9 Draft Maliseet Ethics Guidelines ……………………………………… 10 Foreword Development of the Maliseet Nation Traditional Knowledge (MTK) Protocol highlights the recognition of the importance of Aboriginal traditional knowledge in relation to the environmental issues facing Maliseet traditional territory, the Saint John River (Wolustok) watershed1. The protection of such knowledge has been identified by the Maliseet Chiefs as a crucial component for future relations with non-Aboriginals, as increasing development activity continues to cause concern for all parties on the best way to proceed, in the spirit of cooperation and with due respect for Maliseet Aboriginal and Treaty rights2. The protocol also addresses past problems with research projects such as lack of consultation of Maliseet people, lack of meaningful community involvement, lack of benefit from research, lack of informed consent, lack of community ownership of data (including analysis, interpretation, recording or access), and lack of respect of our culture and beliefs by outside researchers. Initiated by the Maliseet Nation Conservation Council and produced through the combined efforts of informed Maliseet Elders, leaders, committees and grassroots volunteers, this protocol identifies the methods developed by the Maliseet Nation for the proper and thorough collection and use of traditional ecological knowledge (TEK). -

Olive Dickason

Dickason first became aware of her Métis ancestry as a young adult upon meeting some Métis relatives in Regina. Honouring her ancestors properly became a goal that would give her future academic work the deepest personal meaning. But before that, she entered the workforce. She began a 24-year career in journalism at the Regina Leader-Post and subsequently, worked as a writer and editor at The Winnipeg Free Press, The Montreal Gazette, and The Globe and Mail. She pro- moted coverage of First Nations and Women’s issues, becoming the Women’s Editor at both The Montreal Gazette, and later The Globe and Mail’s daily newspaper and magazine. At age 50, Dickason decided to continue her education, entering the Graduate program at the University of Ottawa. She had to struggle with faculty preconceptions regarding Aboriginal History – including arguments that it did not exist – before finally finding a professor to act as her academic advisor. Dickason completed her Master’s degree at the Olive Patricia Dickason University of Ottawa in 1972, at the age of 52. She Honorary Doctor of Letters went on to successfully defend her Doctoral Thesis, entitled The Myth of the Savage. Born in Winnipeg, Olive Dickason is widely Dickason then authored Canada’s First Nations: acknowledged as the key figure in making A History of Founding Peoples from the Earliest Times, Aboriginal History serious study in Canada’s the most definitive text on the subject at the time, academic world. and still widely in use. She has had to face much adversity in her life and, Dickason taught at the University of Alberta from throughout, she has persevered in the roles of student, 1975 to 1992, and is currently an adjunct professor journalist, mother, scholar, elder, and role model. -

National Aboriginal Achievement Foundation

NATIONAL ABORIGINAL ACHIEVEMENT FOUNDATION • ANNUAL REPORT 2006/2007 • Table of Contents Message from the Chair. page 2 Message from the CEO . page 3 National Aboriginal Achievement Foundation . page 5 Corporate Development . page 6 Communications . page 6 Finance & Operations . page 7 Education . page 7 Special Projects . page 8 Taking Pulse. page 10 Blueprint for the Future . page 12 The 2007 National Aboriginal Achievement Awards . page 14 The 2007 National Aboriginal Achievement Award Recipients . page 16 Special Named Scholarships . page 18 2006-2007 Scholarship Recipients . page 19 Supporters . page 49 Financial Statements. page 55 Message from the Chair of the Board As we move forward, we find ourselves on stronger ground, as The reason for the Foundation’s existence, our First Nations, we have overcome a number of challenges these past few years Inuit and Métis youth of Canada, never cease to amaze me as to owing much to the leadership of Roberta Jamieson. Her drive their resiliency, and their ability to overcome challenges in order and determination to bring the Foundation into the 21st to pursue their dreams. The Aboriginal youth of Canada exude Century ensuring that we are providing the standard of service the promise of greatness and I am honoured to serve them as that the Foundation has become known for – Excellence – is part of the National Aboriginal Achievement Foundation, they remarkable and we are grateful to have a person such as Roberta truly are Canada’s future. leading the Foundation. On behalf of the Board of Directors, I congratulate her and the Foundation staff for another fantastic The future is bright due to the continued support of our many job well done. -

Tea and Bannock Stories: First Nations Community Poetic Voices

Tea and Bannock Stories: First Nations Community of Poetic Voices a compilation of poems in celebration of First Nations aesthetic practices, such as poetry, songs, and art, that speak about humankind’s active relationships to Home Land and her Beings Simon Fraser University, First Nations Studies compiled by annie ross Brandon Bob Eve Chuang and the Chuang Family Steve Davis Robert Pictou This project was made possible by the Social Sciences and Humanities Council of Canada (SSHRC) Background: First Nations Studies, the Archaeology Department, and the School for Contemporary Arts at Simon Fraser University, Burnaby, British Columbia, is the origin place for Tea and Bannock Stories. Tea and Bannock Stories is a grass-roots, multi-generational, multi-national gathering of poets and artists. Together we have learned from and informed one another. Our final result is this compilation of poems and images presented in a community event on Mother Earth Day, April 21, 2007, at the Vancouver Aboriginal Friendship Center amidst family, friends, songs, dances, art, poetry, tea, and bannock. Tea and Bannock Stories began as research inquiry into poetic First Nations aesthetic forms between aboriginal artists and poets, the principal researcher, annie ross, SFU student researchers Brandon Bob, Eve Chuang, and Simon Solomon, and students during the years 2004 – 2007 to investigate First Nations environmental ideas in the poetic and visual form1. First Nations Artist Mentors to SFU students were: Chief Janice George and Willard Joseph (Squamish), Coast -

Indigenous Peoples/First Nations Fact Sheet for the Poor Peoples Campaign

Indigenous Peoples/First Nations Fact Sheet For the Poor Peoples Campaign “Who will find peace with the lands? The future of humankind lies waiting for those who will come to understand their lives and take up their responsibilities to all living things. Who will listen to the trees, the animals and birds, the voices of the places of the land? As the long forgotten peoples of the respective continents rise and begin to reclaim their ancient heritage, they will discover the meaning of the lands of their ancestors. That is when the invaders of North American continent will finally discover that for this land, God is red”. Vine Deloria Jr., God Is Red Indigenous Peoples and their respective First Nations are not only place-based peoples relationally connected to their traditional homelands, but have their own distinctive cultures, traditions, and pre-colonial and colonial histories since European contact.1 The World Bank 2020 Report states the global Indigenous population is 476 million people, or 6% of the world’s population, live in over 90 countries, and through the cultural practices of traditional ecological knowledge, protect about 80% of the world’s remaining biodiversity2. Within the United States (U.S.), Native Americans/American Indians/Alaska Natives/Native Hawaiians comprise about 2% of the entire United States population. There are, indeed, more than 6.9 million Native Americans and Alaska Natives3, and in 2019, there were 1.9 million Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders4. Within the U.S., there are 574 federally recognized Indian nations, 62 state-recognized Indian nations5, and hundreds of non-federally and non-state recognized Native American nations6. -

2000 Canliidocs 144 Given Rise to Confusion and to Controversy, Niveau Provincial

458 ALBERTA LAW REVIEW VOL. 38(2) 2000 "STILL CRAZY AFTER ALL THESE YEARS": SECTION 88 OF THE INDIAN ACT AT FIFTY KERRY WILKINS• Section 88 of the Indian Act, which provides, as a La clause 88 de la Loi sur les lndiens qui regil, en matter of federal law, for the application of much tant que JoiJederale, I 'application de nombreuses provincial law to Indiaru, is fifty years old this loi.s provinciales sur /es Indiens a cinquante ans year: an apt time to review what we know of its cette annee. Le moment est done tout indique pour origins and to reflect on the impact it has had on revoir ce que nous connaissons de ses origines et de the Canadian law of Aboriginal peoples. This nous pencher sur ses retombees sur le droit article attempts just such an assessment. canadien des Autochtones. Cet article se veut une As it turns out, we know very little about the tel/e evaluation. · reasoru for s. 88 's enactment; when introduced, it II s 'mere que nous savons peu de choses sur attracted almost no scrutiny from the public, in /'adoption de cette clause. Lorsqu 'elle a ete Parliament, or even at Cabinet. In the years since, presentee, elle n 'a pas vraiment attire /'examen du we have paid dearly for that inattention. By public, du parlement ou mime du cabinet. Depui.s, happenstance, it has managed to Jul.fill its original nous avons paye cher pour celle inattention. Elle a, mandate to protect Aboriginal peoples' treaty rights par hasard, reussi a remp/ir son mandat original de from the impact of standards enacted provincially. -

Insight-No19.Pdf

IRPP The Emerging Policy Insight Relationship between Canada and the Métis Nation January 2018 | No. 19 Janique Dubois Summary ■■ The Supreme Court of Canada decided in 2016 that the federal government’s jurisdiction over First Nations and Inuit people extends to the Métis. ■■ Initiatives such as the 2017 Canada-Métis Nation Accord suggest the federal government is committed to deepening its relationship with the Métis. ■■ A true government-to-government relationship will require an ongoing commitment to respect the Métis as partners in policy-making Sommaire ■■ La Cour suprême du Canada a établi en 2016 que la compétence constitutionnelle du gouvernement fédéral à l’égard des Premières Nations et des Inuits s’étend également aux Métis. ■■ Des initiatives comme l’Accord Canada-Nation métisse de 2017 indiquent que le gouvernement fédéral s’engage à renforcer ses relations avec les Métis. ■■ Pour mettre en œuvre de véritables relations de gouvernement à gouvernement avec les Métis, il faudra un engagement permanent où les Métis sont des partenaires. ON APRIL 13, 2017, Métis Nation President Clément Chartier and Prime Minister Justin Trudeau signed the Canada-Métis Nation Accord. Through it, Métis and federal leaders have agreed to develop priorities and programs jointly and to advance Métis rights, claims and aspirations. As the Prime Minister declared, “we now have a solid foundation upon which to move forward with a respectful, renewed Métis Nation-Crown relationship, for the benefit of all Canadians.”1 This historic agreement is part of Canada’s commitment to advance reconciliation with Indigenous peoples through nation-to-nation relationships. The signing of the Canada-Métis Nation Accord marks a significant shift in the federal government’s approach to the Métis. -

The Drafting and Enactment of the Maine Indian Claims Settlement Act Report on Research Findings and Initial Observations

The Drafting and Enactment of the Maine Indian Claims Settlement Act Report on Research Findings and Initial Observations February 2017 Nicole Friederichs Amy Van Zyl-Chavarro Kate Bertino Commissioned by the Maine Indian Tribal-State Commission Contact Information: 120 Tremont Street Nicole Friederichs Boston, MA 02108 Practitioner-in-Residence Tel.: 1-617-305-1682 Indigenous Peoples Rights Clinic Fax: 1-617-573-8100 Suffolk University Law School Email: [email protected] Acknowledgement The Maine Indian Tribal-State Commission (MITSC) is honored to offer this thorough review of the crafting of the Federal Maine Indian Claims Settlement Act, 25 U.S.C. §§ 1721-1735. In June of 2014, the MITSC completed the Assessment of the Intergovernmental Saltwater Fisheries Conflict between Passamaquoddy and the State of Maine where the MITSC offered the following framework: The Maine Indian Claims Settlement Act, (MICSA), was passed in October of the same year [1980]. The MICSA gave federal permission for the [state Maine Implementing Act] (MIA) to take effect while retaining intact the federal trust relationship between the federally recognized tribes of Maine and the US Congress; and placed constraints on the implementation of the MIA. Of particular interest to the inquiry into the saltwater fishery conflict between the Passamaquoddy Tribe and the State of Maine are the following provisions of the federal act: 1. MICSA (25 U.S.C. § 1735 (a)) provides that “In the event a conflict of interpretation between the provisions of the Maine Implementing Act and this Act should emerge, the provisions of this Act shall govern.” The provisions of the federal MICSA thus override the MIA provisions when there is a conflict between the two.